Bonobo: “If I look at a piano I tend to reach for the same keys and progressions, whereas with modular you often don’t even know what key you’re in"

After years of touring, Simon Green found himself lacking creative stimulus. We learn how modular synths fuelled his imagination

Two decades into his career and Simon Green’s Bonobo is still reaching previously unexplored heights.

Having debuted with the downtempo, trip-hop vibe of Animal Magic in 2000, his multi-layered sample-based approach to production has enveloped jazz and world music styles, attracting numerous Grammy nominations. Mainstage performances at major festivals raised his profile further and he even climbed towards the upper reaches of the UK chart with his 2017 album, Migration.

Increasingly enmeshing electronics and live instrumentation, Green’s onstage setup has become increasingly expansive. However, his gruelling live schedule took its toll. Stimulated by writing on the road, the pandemic now found Green wrestling with his own isolation and seeking impetus.

Investigating the world of modular synthesis on Bonobo’s seventh album, Fragments, the producer’s self-made systems coexist with live instrumentation, sample-based strings and upbeat rhythmic frameworks.

Your last album Migration was a top 5 hit. Does that sort of success hold meaning for you?

“I’m from a generation where the charts do mean something – back in the day I’d listen to the Top 40 on the radio every Sunday night. These days, it’s all about the first week and whatever happens after that is fair game, so while that sort of success is not everything it is a nice thing to have on your metaphorical shelf.”

Your debut album Animal Magic could definitively be described as trip-hop, but do you find these labels cease to apply within electronic music today?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I’ve never been that fond of genre-assigning. Trip-hop was a very specific scene that was a lot narrower than people imagined. It went on for a few years in a few places, and I was definitely influenced by it, but by the time I started releasing stuff in the early 2000s there was this whole ‘chillout’ scene that I spent years trying to keep at arm’s length.

I’d end up just nudging a kick drum around in Ableton for a few hours… it was that paradox of having all the time in the world but nothing to say

"You get all these little micro-genres too, like vaporwave and chillstep, which are quite funny actually. Stick a ‘wave’ on anything and it seems to be a genre right now.”

They come and go, but techno and house do look like they’re set to last forever…

“Even more so than drum & bass, although it’s something completely different now to what it was in the ’90s. But yes, we’re at a point where classic stuff from the techno era is becoming referential and people are starting to emulate it, especially the period when a lot of that music was made with all those little Roland boxes. It seems to be bigger than ever now.”

We read that your touring schedule has been so relentless in recent years that you decided to give up your apartment and were technically homeless?

“My home base at the time was New York but my touring schedule for the year was so gruelling that I wasn’t sure whether I was going to stay there or not, so I just put all my stuff in storage and gave up the apartment. I spent a year bouncing around between places, which was quite liberating and fun for a while, but not sustainable.

"I’m about to do it all again soon, so I’m a little apprehensive about how I approach touring. Having re-evaluated my relationship with playing live, I’m definitely going to nest a little more between shows and try not to burn myself out. On my last tour, if I had any days off I’d go out into the country or hike up a mountain, anything to get out of the environment of being on a bus or backstage at a venue.”

When your career’s at full throttle, is there an element of feeling obliged to perform lots of shows because you never know when it’s all going to end?

“There’s definitely an element of that, but you’re also striving to push a project as far as you can take it. It’s about taking opportunities, but you have to ask whether there’s a benefit to accepting certain gigs or playing at certain festivals. I do enjoy it; there’s an adrenaline rush that keeps you going, but then it’s suddenly very strange to not be on tour.

On my last record, I was writing stuff in the back of tour buses and at airport boarding gates

"You almost feel like you’ve become institutionalised – like those people who come out of prison after a long stretch and don’t know what to do so they end up going back in [laughs]. Since the pandemic, I’ve got into a routine and felt a little more settled and rooted for the first time in a while.”

What impact do you think a heavy touring schedule has on artistic creativity?

“I find that being on tour and constantly moving is a very stimulating place to be creatively. It’s where all the ideas happen, even if you don’t necessarily have the means to communicate them. On the road, I’ll work a lot on Ableton and always seem to find time to sketch out ideas.

"Right now, I have a studio in my house in Los Angeles that I’m slowly building up, but on my last record, Migration, I was writing stuff in the back of tour buses and at airport boarding gates. It was a surprisingly good way of working and the experiences I was having at the time were a valuable tool to getting my ideas moving. If I stay in one place, I find it harder to do that.”

Were those Ableton sketches basic or were you importing a lot of plugins to help move them along?

“I mostly used Ableton’s built-in plugins mixed with a certain amount of third-party stuff, but I’ve been getting into a lot of tape emulators this time to try to get things sounding a little more alive and applying modulation to stuff. I’d done some work on the Fragments album during 2019, but as 2020 progressed it ground to a halt because I wasn’t feeling inspired.

"It was that paradox of having all the time in the world but nothing to say and I’d end up just nudging a kick drum around in Ableton for a few hours before going out for a walk. When thing started opening up, my creative gears started turning again and I finished the record this year.”

I’ve been getting into a lot of tape emulators this time to try to get things sounding a little more alive

Does the album title refer to psychological fragmentation or is it production-related?

“I’ve always worked in collage. I started from an MPC/hip-hop background, so the title’s a literal thing that references collecting bits of audio, collaging sound on a macro and micro level and the way it’s all put together. I never have expectations when I start an album – I don’t know what I’m waiting for, so it’s more a case of documenting whatever I’m listening to and how I’m feeling at the time.”

Does spending more time in the studio inevitably lead to a better end product or does it just mean more procrastination?

“For me, the more time you spend in the studio the more likely you are to lose perspective. You often sit and listen to what you’re making but have no idea how it really fits together or even what you’re supposed to be doing, so distance is really important to figuring out what’s actually happening.

"By taking the music out of the studio and going for a drive or putting on studio headphones and going out for a walk, it gets re-contextualised and you can instantly hear what needs to be different.”

Ordered chaos: a guide to randomisation, probability and generative music

We understand that using modular synthesis was the bedrock of your creative process on this occasion?

“I’d seen people use modular stuff and already had a good understanding of subtractive synthesis, so I felt like building a very expensive monosynth, but it was only when I saw people doing stuff with resonators, randomisation and probability that things got really interesting for me.

It was only when I saw people doing stuff with resonators, randomisation and probability that things got really interesting for me

"With modular, I like the idea that you can establish a pattern and then decide which notes you want to configure a probability to by defining certain parameters. You still have control over the chaos, you’re just asking for certain aspects to surprise you.”

Have other artists inspired you through their use of modular?

“A lot of it was about doing deep dives on YouTube and watching people who weren’t necessarily releasing music but doing inspiring things with modular. They helped me to discover sound capabilities that I didn’t realise existed. Of course there are loads of great people out there making some really interesting music with modular, like JakoJako, James Holden and Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith.”

Does modular enable you to move beyond writer’s block?

“If I look at a piano I tend to reach for the same keys and progressions, whereas with modular you often don’t even know what key you’re in so you’re doing it all by ear. That definitely enables you to come up with different melodic ideas you might not have thought of when using an instrument of choice.

"I just found the idea of building generative patches exciting, especially how resonators like Rings or the Qu-bit Surface module can sound like acoustic modelling. A lot of the Mutable Instruments stuff is amazing for that.”

At the beginning, were there specific types of sounds you were looking for?

“You can make these very sparse, acoustic, plucked-sounding tones and melodic noises, and by pairing them with a sequencer, Euclidean rhythms and certain clocking methods, you can make a module spit out its own version of a melody that you put into it.

Back in the day I’d sample by digging through charity shop records, this time I’m sourcing stuff from little morning modular jams

"There’s so many ways you can expand and interact with that by clocking and sequencing other modules too. Back in the day I’d sample by digging through charity shop records, this time I’m sourcing stuff from little morning modular jams and using those.”

What lay behind your initial choice of modules?

“It was trial and error – you get a few bits that people are excited about and then it’s a case of living with them until you decide what you want to end up using. For me, I was more interested in using resonators and interesting delays like Make Noise’s Morphagene and Mutable Instruments’ Clouds.

"I moved away from the idea of building some big monosynth, because I’m not trying to make a full, multi-polyphonic album using modular. It’s more about creating interesting parts and melodies, in the same way you would with a single instrument, whether it’s an electric piano or guitar.”

Have you benefitted from moving your creative impetus away from the laptop?

“With modular you can patch in quite complicated sounds that would take a lot longer and more mouse work on a laptop. I like the idea that a lot of these modules don’t have menus and everything is tactile and responds to an LFO moving a VCA level or a filter. That’s been an inspiring way of working and I feel that you’ve always got to have something that feels new and exciting to you.

"Going back to the very beginning, the idea of being able to loop a drum break on a sampler was a big wow moment for me, so I’m always looking for things that will get me excited about the process and I found that modular fit the bill this time around.”

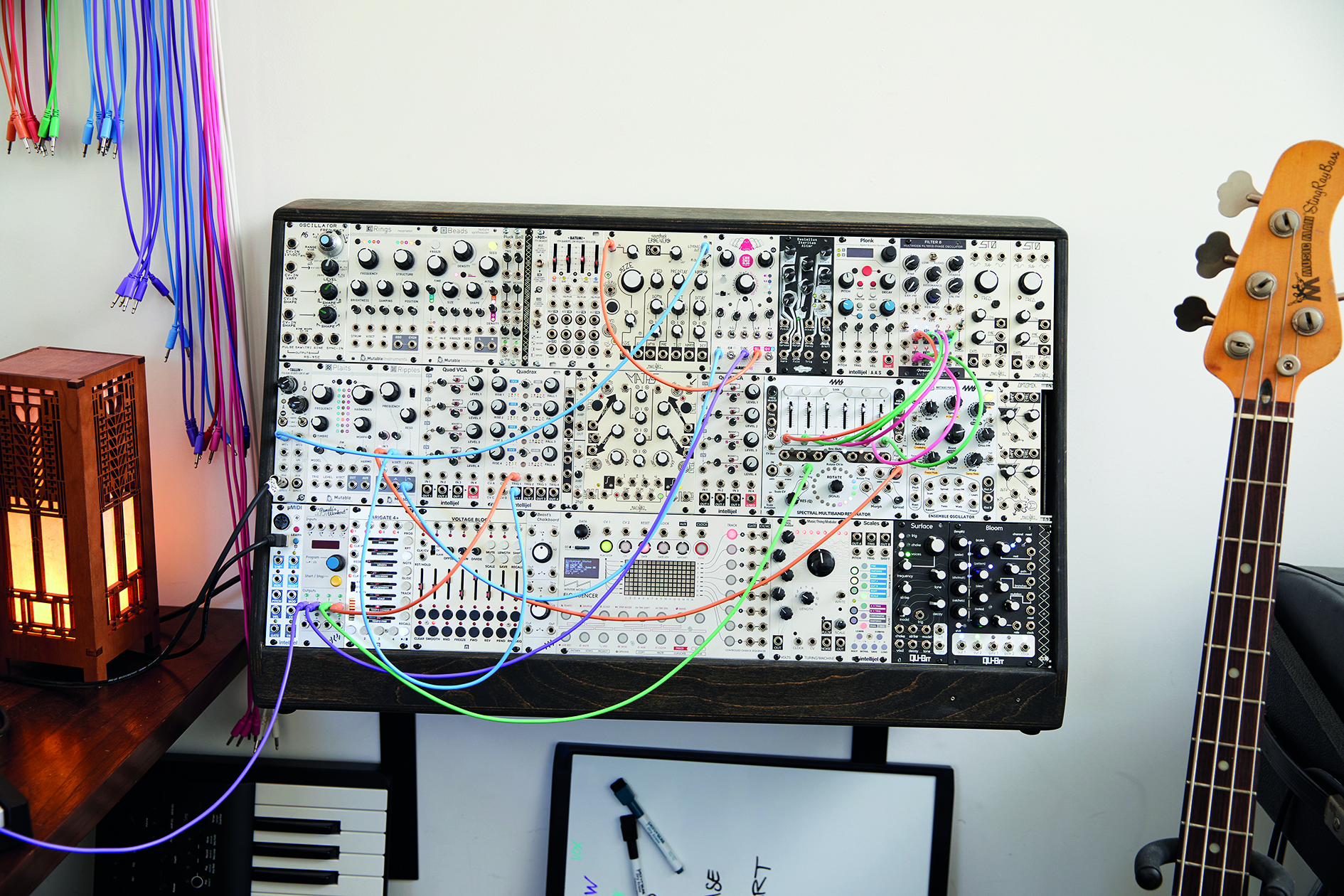

So at present you’re operating from a small Eurorack case?

“I have two actually, but they’re not small [laughs]. One is based around Moog stuff like the Subharmonicon, Mother-32 and the DFAM percussion synth linked to some auxiliary LFOs, function generators and effects.

At first, she did some conventional harp playing and then we tried to do something a bit weirder, using kitchen utensils to hit the strings

"The other rack comprises everything else, so a lot of the Mutable Instruments and Make Noise stuff and a lot of sequencers like ALM Busy Circuits Pamela’s Workout, Turing Machine and resonators like 4ms. There’s a lot going on in the second one.”

Are you processing the modular sounds or is that rather unnecessary?

“I’m still processing sounds when I print them in Ableton, which gives me a second way to edit them. I tend to mix as I go anyway, so when I fit sounds into place that’s invariably where they’ll stay until the track’s finished.

"In terms of processing, I’ve always used the Avalon VT-737 Channel Strip for pretty much everything, whether it’s guitars or synths, but I recently picked up an NT-02A Overstayer Saturator, which is a dual-channel saturator and high-pass filter that gives you some really big bassy, resonant tones.

"If you get a couple of channels going through the modular, then it’s already sounding beefy, but I find the saturator really warms sounds up as they come in through it.”

We read that you sourced harp sounds from sessions with harpist Lara Somogyi. Why that particular instrument?

“When I’m sampling and flipping through folk records or spiritual jazz stuff, I feel like I’m always drawn towards harmonic, plucked textures. I met Lara through a mutual friend, Olafur Arnalds, who was in town playing a show and eventually became interested in working with her.

"We organised a session but rather than have Lara playing parts to ideas I already had, I just wanted to collect some textures. We did so much together that we basically made a sort of harp record as a starting point for sample sourcing, and a lot of that ended up on the album.”

What was the setup for that session?

“Lara has a guitar that she uses for sample pack and library recordings, so she already had a pretty good setup. We just used a digital interface to get some interesting textures on the low end, a room mic and tracked the two channels. At first, she did some conventional harp playing and then we tried to do something a bit weirder, using kitchen utensils to hit the strings with, which was fun.”

You can hit a keyboard chord and get a room sounding like it’s full of musicians, but nothing can really replace the human touch

A lot of those sounds feature on the dreamy opener Polyghost, but what was Miguel Atwood-Ferguson’s role on that track?

“I’ve been recording orchestral elements and woodwinds on every record since my third album Days to Come. Some of the libraries, like Spitfire and Slate + Ash, are incredible and back in the day I’d bulk up a lot of virtual sounds with MIDI and add some top lines with live instruments to give them flavour, but I liked the work Miguel had done with artists like Flying Lotus.

"He was one of the few people I managed to get in a room and hang out with during the pandemic, so he did the string arrangements on Polyghost and the big string parts at the end of Tides with Jamila Woods. His strings were originally in the body of the track, but they sounded so good that I ultimately turned the volume down on everything else and let them have their moment at the end.”

Are virtual instruments a long way from competing with live instrumentation in your opinion?

“You can hit a keyboard chord and get a room sounding like it’s full of musicians, and the articulation on some of these libraries is quite clever because the sounds do start to evolve, but as much as you can emulate strings with expression controls nothing can really replace the human touch in my opinion.

"One of the problems is that sample libraries are too big in terms of data, but additive synthesis will be able to do what they can within a fraction of the size, so I’m curious to see where that all goes eventually.”

What other musicians did you invite to source acoustic sounds from and was that mostly accomplished by exchanging audio files?

“Miguel was often sending me bulks of a session, but I played a lot of electric piano, guitar and other bits and pieces myself so wasn’t sourcing a huge amount from other people.

"I find it’s better to work remotely because when you’re in a room together the clock is always on, whereas if you leave people to do their own thing and send stuff over, they have the space to stretch out and contribute in their own time.

"With the exception of Lara, I had a very firm idea of the parts I wanted, although sometimes it took a little finessing to chart the strings and get them to a place that would work for a string arrangement.”

We read that you reached out to a number of vocal contributors but had a breakthrough moment with Jamila Woods when you received her vocal for Tides?

“We reached out to quite a few people who we were interested in contributing, but everyone seemed to be having a bit of a hard time and ended up doing their own thing. Jamila texted me one evening to tell me she’d recorded a vocal and she smashed it.

"It was actually the same take that ended up on the record and an inspiring moment because it told me I had something that was starting to resemble an album. Usually I have those moments quite early on, and it’s easy to get into the rest of the record when you know you have a central tune or something you’re really excited about.”

There isn’t really one place where all the drums are coming from, the lines become blurred between a percussive sound and one that’s based on abstract textures

The track Otomo has some really nice choral chanting. What’s the story behind how the song came together with O’Flynn?

“The chants are an archived folk recording of a very old sample of a Bulgarian choir from the 1920s. It had loads of texture and a big reverb feel, which made me very excited about it, so I re-harmonised a few chords around the sample to see where it would go.

"At one point I was having a bit of trouble deciding where to take the track in terms of its arrangement, so I asked O’Flynn because I really like how he arranges his stuff and he ended up adding quite a lot.”

Do you use beats as a tempo guide or are they built into the arrangements while a track’s already underway?

“I know a lot of people do but I never start with drums. I’ll start with either a melodic or polyphonic sound or texture and try to apply drums by pulling a rhythm out of those abstract shapes and seeing what they might suggest to me.

"I’ll sometimes use the modular stuff for creating hi-hats, other times I’ll use clips arranged in Ableton using some of the pads on a Drum Rack or get hold of an audio percussion sample and layer it all up.

"The key to my beat making is that there isn’t really one place where all the drums are coming from and the lines become blurred between a percussive sound and one that’s based on abstract sounds and textures.”

Your beats have always been quite abstract and crunchy…

“I like using saturators and discovered the joys of distortion this time around. I use Soundtoys’ Decapitator quite a lot to add character and ToneBoosters’ ReelBus tape emulator, which glues everything together really nicely. I end up sticking that on a lot of channels because you can group drums through it to give them that nice crunch you mention.

"Ableton Drum Buss is another great tool for pulling out resonant thumps from a group of drums. Tuning percussion is definitely a big thing, but I just try to feel things out and tune them by ear. I also like the idea of experimenting and putting stuff through Ableton’s warp engines and algorithms where you can detune things in a really nice way and make some of the sounds stand out a bit more.”

Your live shows are quite distinct from the end product, especially as you use a live band. Presumably, you don’t want to stick to the script?

“For me, playing live is a good way for the record to live in a different form, but I find that as the tour progresses, things change. A little accident might happen and that will become a big feature of a track the next night, so I welcome the idea of the live show evolving.

For me, playing live is a good way for the record to live in a different form

"I’ve got a slightly augmented version of the band that I used last time and I’m in the process of pulling the record apart to see how it might work on stage, but I like the idea of working with a stage full of people. You think you have an idea of how certain parts will come across when you give them to musicians to play, but they always surprise you.”

To what extent are you balancing electronics with conventional instruments on stage?

“Ableton is a big part of it, so there’s still a lot of electronics up there and I’m sure that there’ll be a lot of modular as well, but there’s a drummer, woodwind and keys and I play bass, some drum synths and do all the Ableton bits too. For a quite small show, the default is to have around six people on stage, for the bigger shows like the one we did at the Alexandra Palace we’ll use a full orchestra and have a big visual video element too.”

Bonobo's new album, Fragments, is released January 14th on Ninja Tune.

Electronic Musician magazine is the ultimate resource for musicians who want to make better music, in the studio or onstage. In each and every issue it surveys all aspects of music production - performance, recording, and technology, from studio to stage and offers product news and reviews on the latest equipment and services. Plus, get in-depth tips & techniques, gear reviews, and insights from today’s top artists!