What makes an Oscar-winning song? We break down the music theory behind Billie Eilish's What Was I Made For?

We put Eilish's haunting contribution to the star-studded Barbie soundtrack under the musical microscope

Billie Eilish’s What Was I Made For?, written for the Barbie movie, just won the Oscar for Best Original Song, weeks after taking home the Golden Globe for Best Original Song and receiving five Grammy nominations, including Song of the Year.

Because I have a daughter in elementary school, I have seen the Barbie movie multiple times. There has been so much Barbie discourse already, and I don’t have much to add to it. I agree with my son’s review: “It was weird and good. Kind of one big ad, though.”

Barbie's soundtrack is as ambitious as the movie itself. Featuring original songs from an impressive collection of artists that includes Charli XCX, Lizzo, Nicki Minaj and Tame Impala, among many others, the album was executive-produced by Grammy-winning hitmaker Mark Ronson.

Perhaps the most interesting song on the soundtrack was penned by Billie Eilish and her brother and creative partner Finneas. Today, we're going to dig into the theory and production behind Eilish's Golden Globe-winning What Was I Made For? to find out what makes the song work so well.

Here’s a live performance of What Was I Made For? from the Academy Awards ceremony.

This performance clarifies what the production and layering add to the official version. It also demonstrates how quietly Eilish sings. You might notice that her breathing sounds weirdly loud compared to the studio version. This is not because she breathes in any kind of unusual way; it’s just that for the recording, they went through and made all the breaths quieter, or removed them entirely.

I am several decades older than Billie Eilish’s core fan base, but I have heard her music all over the place, and I have seen many pictures of her staring at the camera with her trademark expression of dead-eyed contempt. I knew her basic backstory, that she writes and produces everything with her brother Finneas at home using Logic Pro, and and that both of their parents are actors and musicians. In researching this article, I learned that her full name is Billie Eilish Pirate Baird O'Connell, which is delightful.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

What Was I Made For? is not Billie and Finneas’ first song in a kids’ movie. They also wrote the fictional boy band songs for Turning Red, which are total bangers. In spite of its magical elements, that movie is the most accurate portrayal of middle school I have seen. My kids find the cringiest parts too stressful to even watch.

There are lots of remixes of What Was I Made For? out there, both official and not. My favorite is this drum ‘n’ bass version.

Finneas explains the writing and production of What Was I Made For? in this episode of Variety's Behind The Song.

The only acoustic instrument on the track is a Petrof piano. The other instruments include drums, guitar that has been severely distressed via the SketchCassette plugin, Mellotron strings, vibraphone, a Kontakt synth pad, electric bass, and pipe organ running through an arpeggiator.

Mark Ronson and Andrew Wyatt added a delicate (presumably synthetic) orchestral arrangement. Eilish’s voice is stacked and layered like any mainstream pop song, with doubling, harmonies, and ad libs. However, these layers are mixed quietly, and at times are almost imperceptible at times. You don’t get the sense of a big thick stack of vocals; they are more of an ambient, pillowy presence.

The tempo is a very laid-back 78 beats per minute, with enough subtle variation to suggest that it wasn’t recorded to a click or metronome. Every note of the melodies and chords are from the C major scale, the white keys on the piano. It’s seemingly nursery-rhyme simple, though there are a few intriguing twists.

The intro is a three chord loop.

| C Em | Fmaj7 |

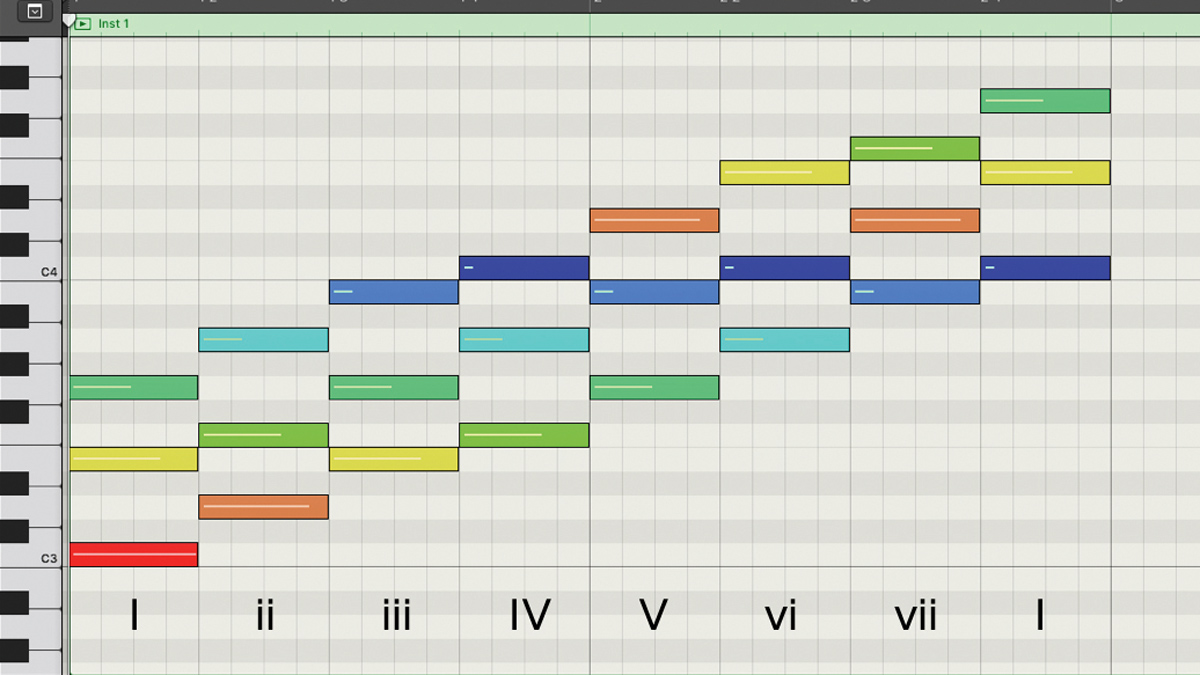

You can make any diatonic chord in C major by playing a note and then going up, skipping every alternating scale degree. Here’s an interactive explainer on making chords from the C major scale.

To make a C chord, you start on C, skip D to land on E, and then skip F to land on G. This three note chord (C, E and G) is called a triad. The next chord, Em, is a triad too: start on E, skip F to land on G, and skip A to land on B.

5 music theory tools to help you make better electronic music

Notice that it has two of the same three notes as C. It almost sounds like an extension of the C chord rather than a real harmonic movement. Pop songs don’t use the iii chord (the chord built on the third degree of the major scale) very often, maybe because it’s too wistful and ambivalent.

The next chord, Fmaj7 (F major seventh), is more complicated than the first two, because it uses four notes rather than three. Start on F, skip G to land on A, skip B to land on C, and skip D to land on E. This chord has a more sophisticated sound to it than the triads we’ve been hearing so far.

The interval between F and E is a very dissonant one, and even though it exists within the safe confines of the C major scale, it’s still a source of tension. Also, the top three notes of Fmaj7 form an Am chord, so even though it’s really a major chord, it has that suggestion of minor hidden inside it too.

Verse 1 repeats the intro loop three times, and then the fourth time it’s slightly different:

| Am Em | Fmaj7 |

All we’ve done here is replace the C with Am, but because the song has been so simple and repetitive up to this point, the change sticks out. The Am chord has a special relationship with C, because it’s the tonic chord in the key of A minor, the relative minor key to C major.

These two keys contain the same seven notes, C, D, E, F, G, A and B. But when you center A rather than C, the mood and feeling of the notes changes completely. It’s like the relationship between the words SPECTRE and RESPECT: same letters in the same order, but changing the starting letter changes the meaning.

Anyway, the whole verse form repeats, and then the ending two bars are slightly different:

| Am Em | Fmaj7 Em |

Next comes a new section, which I would call the “chorus” because it’s where the chorus would typically go. It doesn’t feel like a chorus, though. It just has some slightly different harmony and melody from the verse, and an almost imperceptible buildup in the arrangement. This section begins with two new chords:

| Dm | G7 |

Current pop uses the same chords that Mozart did, for the most part, but it uses them differently

The Dm is another simple triad: D, F and A. The G7 is a four-note chord like Fmaj7: G, B, D and F. In Western European tradition, G7 is the most important chord in the key of C major, other than C itself. It’s called the dominant chord. It creates a tension that is resolved by the return to the tonic chord C, home base. This dominant-tonic resolution is the main structural element of European classical music. Current pop uses the same chords that Mozart did for the most part, but it uses them differently.

In Mozart, there is a clear structure of tension and release, a sense of goal-oriented direction. You start on the tonic, you go on a journey that culminates in the crisis of the dominant, and then you resolve with a palpable sense of relief back to the tonic.

In a Billie Eilish song, there isn’t that sense of epic narrative. The chords are just different places to be, locations that you drift through. In What Was I Made For?, the movement from G7 to C is in the middle of the phrase, a structurally unimportant position, and it doesn’t feel like a climax or a conclusion.

After Dm and G7, the “chorus” resumes the loop of C, Em and Fmaj7. The loop continues through the end of the section, on through a short break, and into the next verse.

A slow and simple song that only uses the white keys on the piano might normally sound like a nursery rhyme. This one doesn’t, though

A slow and simple song that only uses the white keys on the piano might normally sound like a nursery rhyme. This one doesn’t, though. First of all, nursery rhymes don’t use the iii chord too often. Second, the melody is too syncopated. Listen to the opening line, “I used to float.” The word “float” comes in a little before the first beat of the verse, just a half a beat early. In the next line, “now I just fall down”, the words “fall” and “down” are half a beat earlier than where you would naively expect them.

The same anticipations happen in every subsequent line. On the chorus, “'Cause I, I, I don't know how to feel”, the “‘cause” is anticipated like you’ve come to expect. But then that first “I” is delayed a half a beat. The next time you hear “I don't know how to feel”, the rhythm is different, with a delay on “how”. This is not Charlie-Parker-level rhythmic complexity, but it’s enough to locate the song in the pop idiom.

10 music theory tricks every producer and songwriter should know

Remember how the live version demonstrates how quietly Billie Eilish sings? The dynamics of the recording are pretty weird when you think about it. On the one hand, she’s nearly whispering, but on the other hand, she seems to be located on the far side of a gigantic cavern. In real life, you wouldn’t be able to hear her at all, much less understand her. We are used to this kind of unphysical sonic space in recorded music, but it’s worth pausing a second to recognize how surreal it is.

Classical voice comes from the time before microphones. Singers had to be heard and understood in every seat of a large auditorium, over all the instruments. This requires good strong breath support and control of tone, as well as exaggerated articulation.

The typical way to record classical singing is to recreate the experience of being in the concert hall. You place the mics at a distance from the performer, so you are mainly capturing the sound of their voice bouncing off the walls and ceiling of the hall rather than the sound coming directly out of their mouth. Check out this video of Maria Callas: the microphone is not visible in the shot, because it was nowhere near her.

This is not the way that you record pop vocals. Ever since the crooner era, engineers have used a technique called close miking, which is exactly what you think it is: the microphone is a few inches away from the singer’s mouth, or even closer than that.

Not only does this sound different from classical-style miking, but it also enables a radically different singing style. You can sing quietly and conversationally, using casual enunciation, and still have every detail of your voice be clearly audible. For example, Al Green sings so quietly on this track that he’s practically doing ASMR.

We are all so used to close-miked singing that we can’t experience how weird it actually is. In the early days of recording, singers were cutting grooves into wax cylinders with the physical force of their lungs. Bessie Smith sounds like she’s shouting because that was the only way she could be heard on the recording, the same as when she was singing unamplified in a room.

But starting with electrical recording, it was suddenly possible to sing quietly and be heard just as clearly. This was a shockingly intimate experience! You weren’t hearing Bing Crosby as if he were on a stage a hundred yards away; he sounded like he was murmuring directly into your ear.

If singing unamplified in a concert hall is like tennis, singing into a microphone is like ping-pong. They are superficially similar activities, but they have very different physical demands. Concert hall singing requires both precision and power. Microphone singing requires just as much precision, but hardly any power.

Even though classical singers are “better” than pop singers, they do not necessarily do well in a close-miked situation. The over-enunciation you need in the concert hall sounds stilted and awkward in the vocal booth. The “correct” technique can sound excessively formal and grandiose.

In a sense, mic singing is “easier” than classical singing. To project like Maria Callas requires years of rigorous training. To croon like Bing Crosby or Billie Eilish, you just come as you are. (Bing Crosby did in fact have a trained voice, but he didn’t need it for his style.)

That does not mean that you can stick just anyone in front of a microphone and have them sound good, though! The intimacy of microphone singing makes it psychologically intense, like being in bed with the listener. That may not be so physically demanding, but it does require emotional strength.

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.

With the same mesh-head playability and powerful new Strata module as its bigger brothers, Alesis Strata Club brings a new compact form to its best-selling range

"This is the amp that defined what electric guitar sounds like": Universal Audio releases its UAFX Woodrow '55 pedal as a plugin, putting an "American classic" in your DAW