Verdine White holds it down and powers it forward with Earth, Wind & Fire in Hollywood, Florida, 2010. © Sayre Berman/Corbis

Verdine White is no stranger to compliments. As Earth, Wind & Fire's one and only bassist for 42 years now, he's used to fans stopping him to rave about a new album, a new song or a recent gig. But lately, White has noticed the sentiments have taken on a deeper, more emotional tone.

"People thank us for just being who we are," he says. "All the music we've made, the shows, making people feel good - those are big moments in everybody's lives. And it's very meaningful to hear those kinds of comments. That's why we do what we do."

The accomplishments of Earth, Wind & Fire, now celebrating their fifth decade in the business, are considerable: over 90 million albums sold, six Grammy wins (with 20 nominations), the distinction of being the first African-American group to sell out Madison Square Garden, along with induction into just about every "hall of fame" invented.

And, of course, there are the songs: Shining Star, That's The Way Of The World, Getaway, September, Mighty Mighty, Let's Groove, Sing A Song - stone-cold classics, each and every one, all of them driven by Verdine's exquisite bass playing, by turns thunderous and supple, full-bottomed funk and high-minded jazz.

With a US tour about to begin and a brand-new EWF album on the way, White sat down with MusicRadar to discuss his approach to the bass, why brother Maurice is his biggest musical influence, what gear he uses and how he really feels about the group's vintage sartorial choices.

When the band first started, Maurice was the drummer. How were his skills behind the kit?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"He was great. Maurice had a lot of experience as a drummer. He played on hit records, and he knew what was needed. He had a great sound, too. His knowledge of music is so vast. Jazz, gospel, soul - you name it, he could play it."

You've played with a few different drummers in Earth, Wind & Fire - Maurice, Fred White, Sonny Emory and now John Paris. How have you adapted to each one?

"Well, they're all different, but the main thing I've had in common with everybody is that we're all buddies. If the drummer is you're buddy, you're going to play great. It was always a hoot with Sonny, always a good time. John and I are great friends. Fred is my brother, Maurice is my mentor. It's like being married. The drummer and bass player have got to be married; it can't just be a bunch of cats up there playing."

And, of course, Ralph Johnson on percussion, he's a constant in the band.

"That's right. Exactly. And Ralph is like my brother, so that's what I have in common with him. That's what I have with all the drummers."

Growing up, who were your big musical influences?

"I'd have to say Maurice. He was the one who really opened me up to being a musician. And my father backed it up by making sure I took lessons, which was so important. But mainly, it was Maurice, because he gave me the opportunity to hang around and see his friends and just learn, you know? My bass teacher, Louis Satterfield, was another huge influence. He really taught me so much."

Who were the bassists you listened to when you were coming up?

"Then was James Jamerson. He was the guy I listened to for electric bass - him and Louis. On upright bass, I listened to Ron Carter, Richard Davis, Cleveland Eaton, Eddie Gomez, Scott LaFaro - those were the main guys."

James Jamerson is such a mythic figure. What did you glean from listening to him?

"It was just everything. All the Motown stuff, playing on the The Supremes records and everything else he did. But if you want to hear some great bass playing, listen to What's Going On by Marvin Gaye. Superb bass playing, man. Superb, superb, superb."

What made you decide to pick up the bass instead of a guitar?

"It all started when I walked into a band room and saw an upright bass. Right then, all at once, I just knew that I would love it. It spoke to me. I remember telling Maurice - I must have been 13 or so - that I wanted to play the bass, and he was like, 'The bass?!' But I'm glad I did because otherwise I wouldn't have had a job. All those drummers we just mentioned - Maurice, John, Sonny, Fred - I couldn't compete with them. I'd never have been in the running. So playing the bass gave me a job." [laughs]

Do you remember when you started popping and slapping?

"It came later for me - around '75 or '76. I had my own distinct style already. Larry Graham, he came up in the late '60s doing that. He was the big guy for slapping and popping. But you know, I recently saw something on PBS with Cab Calloway, and his bass player was slapping and popping an upright bass - and this was in the '40s! [laughs] It was something. The guy was slapping and popping like Larry Graham and Louis Johnson and all those cats. I never saw that. I had no idea. So it was going on for a while."

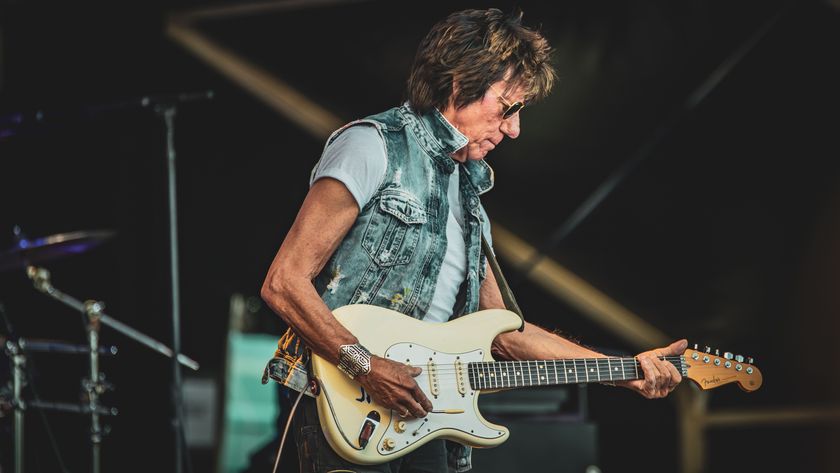

You've been a Fender Jazz player for most of your career. Why did you choose that model?

"At the time I started with it, that's what was around. There weren't a whole lot of choices. There was Fender - and that was before CBS bought Fender, when the basses were really, really good. I still have a Jazz - two of 'em, actually - and I've got a Precision, a Telecaster Bass… a lot. I've got about 30 basses, but they're all different companies. I've got a Yamaha BB 3000, a Roger Sadowsky bass - which is a great bass, truly good. I'm going to get another Sadowsky this summer. I require basses that are handmade. Warwick - they've made me a bass, too, and it's great."

What about gear? How have you changed your setup over the years?

"I've got a rack of things now, all kinds of outboard gear. I've got flangers, tuners, a Marcus Miller preamp - he sent me one to use; it's the same one he uses on stage. Because the halls we play are so different - one night it might be an arena, the next night it's a theater - it's hard to get the sound the same each time. Out of all the instruments, the bass can be the hardest to get consistently right.

"For amps, I'm using SWR. I used to use Acoustic amps on stage, but in the studio I played through an Ampeg B15. And I still use that, the B15. I never tried doing any wild kind of things or experiments. Once I captured my sound, I stayed with it. I never went in for anything nutty or crazy." [laughs]

Let's talk about some of the classic songs. On Shining Star, how long did it take you to work out your parts?

"Not too long. Maurice came up with the beat; he worked out Shining Star in the studio. Later on, I came up with the thirds. Like I did on the song Fantasy, I doubled my bass - a lot of times, I like two or three different bass tracks. I have one basic track and another where I lay down, you know?"

The horns really lead the music on the song Getaway. Did you have to approach that track differently?

"I don't really think about that, to tell you the truth. On that song, the brass came later. I don't think about the brass; I just play the song and hold it down."

Getting a leg up in New Orleans. White says his energetic performance skills "came naturally." © Brad Edelman/Corbis

You do that on Sing A Song - you hold down the bottom, but you still power it forward. You get some cool licks in, almost like a background singer.

"Yeah, yeah, it's like that. Sure. You know, when you've got a great rhythm section and the people you're working with are so good, it kind of all does it by itself. You know what I mean?"

Were a lot of the band's '70s recordings live off the floor, or were the songs built up in pieces?

"They were sections. We didn't record all of us together, us and the horns. We couldn't - there was no way. We'd do the rhythm section first and bring the horns in later."

Has anything changed over the years with how you demo and record?

"We don't demo. We just go in and record. Back in the day we demoed - we'd listen to the songs and figure them out. Because studio time was expensive, you had to demo and know what you were doing. You couldn't afford not to. Now, we just go in. I think demos are a waste of time. There might be a bare bones of a tune, but that's it. If we don't like the tune, we won't do it."

You're such an energetic performer on stage. How do you manage to hold down the fort while being everywhere at once?

"That came naturally, a lot of it. But we were working on it, too. I had to learn choreography and get it together. Over the years, it's evolved. But yeah, you have to hold it down, keep the root of the songs live. If you don't do that, it all falls apart." [laughs]

Which of the band's songs gave you the most trouble in the studio?

"Hmm… Maybe Rock That! from the I Am album. I had to go back and listen to it for a few days before I recorded it. Some tunes sound better after you've played them than when you're listening to them. I still hear some songs on the radio and go, 'Damn, I wish I could have done that better.' [laughs] It happens."

"But I'll tell you, there was a song we did on the soundtrack to Sweet Sweetback [1971's Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song], and I really butchered it, man, I ruined it! [laughs] In fact, there's a really bad note that's still on it. I was young at the time we did that. In those days, we couldn't go back and redo things, you know? That was the first soundtrack that an African-American group had done. I have a copy of the album. I went back and listened to it, and I was like, 'Oops! There it is, that bad note…'" [laughs]

Are there any new bass players who have impressed you?

"There's a lot of great kids out there today, man. A lot. We have more and better bass players today than ever. In the last 50 years, the bass has progressed more than any other instrument. There's so many good players. When I go to the conventions, I can't believe what I hear. They've got 50 years to pull from, everybody from Graham to Marcus, Nathan, Stanley... myself… That's a big foundation for them to build on."

There's a new album on the horizon. What can you say about it right now?

"We're putting the finishing touches on it. The album's going to be called Now, Then & Forever, and it's going to be a two-disc set. The first disc will be new material, and on the other it's going to be previous material with curators commenting on the songs. Clive Davis, Lenny Kravitz, Raphael Saadiq - different people like that. It's going to be cool."

Is the new song Guiding Lights indicative of what the album will sound like?

"Yeah, but even better. The new stuff sounds like Earth, Wind & Fire, so that's why we like it." [laughs]

OK, the outfits. Seriously, now, when you look back at album covers and photos, do you say, "Yeah, those clothes were the coolest" or do you say, "Oh my God, what were we thinking?"

"I say, 'It's cool,' because the workmanship was great. Sometimes the '70s get a bad rap for being a little cheesy, and it's been the stuff of parody, but when really look at the wardrobes, it was great. Really great workmanship. Every era has its time - that's the thing to remember."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)

“We’re looking at the movie going, ‘Urgh! It’s kinda cheesy. I don’t know if this is going to work”: How Chris Hayes wrote Huey Lewis and the News’ Back To The Future hit Power Of Love in his pyjamas

“I thought it’d be a big deal, but I was a bit taken aback by just how much of a big deal it was”: Noel Gallagher finally speaks about Oasis ticket chaos