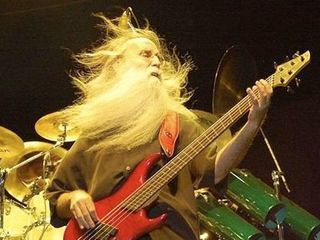

Leland Sklar plays his Warwick bass at the Frankfurt Musikmesse show in 2011. © Arne Dedert/dpa/Corbis

With his foot-and-a-half-long gray beard, bassist Leland Sklar has been one of the most instantly recognizable musicians on stage or in videos for decades. Whether or not he has a recognizable bass sound, however, is of little concern to the session vet - his ability to play pop, rock, jazz, country and easy listening has made him one of the industry's first-call players.

Just a quick glance of the artists Sklar has worked with boggles the mind: James Taylor, Phil Collins, Billy Cobham, Rod Stewart, Linda Ronstadt, Hall & Oates, Jackson Browne, David Bowie, Ray Charles, BB King, The Doors, Peter Frampton, Aaron Neville, Lyle Lovett - all have called upon Sklar's services, and many of them wouldn't think of doing a session without him.

To date, he's performed on over 2,000 albums (including hundreds of film and TV projects) and fits in tours whenever he can. And at 65 years old, Sklar insists he has no intention of slowing down.

"As long as there's work, I'll be there," he says. "In my heart, I feel like I'm 19 years old, back when I started. But what I started into was a world with the James Taylors that led to the Linda Rontadts and Jackson Brownes. There was so much energy then, and I was lucky enough to be in the tenderloin of it all."

MusicRadar caught up with Sklar to talk about how he approaches sessions, what's different about the recording world of today from when he started, what basses and gear he uses, and to find out what advice he has for players looking to break in.

Your career has spanned so many genres. How do you fit in the way you do?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"It's really not a conscious effort. I've listened to a lot of different types of music and have crafted a style that allows me to play most everything. For me to go from country to fusion isn't a leap - I don't change my tone; I don't change anything.

"I'm not an analytical player by any means. I don't think I've ever played a part the same way twice. When I play, it's like I'm having an out-of-body experience. I like playing with people; I like bands. The style of music doesn't really matter. Whether I'm playing Evergreen with Barbra Streisand or playing on Stratus with Billy Cobham, I'm got the same bass and the same attitude."

On stage with Phil Collins during the First Final Farewell tour in 2008.

How would you say sessions are different today from in the '70s?

"They're profoundly different, on many levels. When I started, everything was 16-track, 15 ips, Dolby. We were cutting to analog tape. Right there, the differences are massive.

"When I broke into the scene, LA was full of major studios, and when we went to work, there were at least four, eight, 12 guys on each session. The juices of creativity that flowed through the room were staggering. Nowadays, when I go to work, half the time it's me in some guy's garage where he's got a Pro Tools rig, and I'm just playing bass on some tracks. Sometimes there's not even drums yet.

"How I can impact a track is different now, because it's not the same as sitting with a drummer or a guitar player and working out parts. When it's just you sitting there, you're restricted by what the guy has on his machine. You do the best you can, but it's not as creative an environment as it was when I'd around the room and there's Jeff Porcaro or David Foster or Jay Graden - all these different guys."

You kind of broke in right around the time that the Wrecking Crew were breaking up.

"I talk about this with some of the guys from my generation, who came up a little bit after the Wrecking Crew. We feel that the baton was passed to us. The only problem is, there's nobody for us to pass the baton to.

"I remember my first time in a studio, it was 1966 and I was in a band, and the musicians that were hired to play on the record were people like Carol Kaye and Hal Blaine, and the next few days there's Earl Palmer and Mike Melvoin and Jim Gordon. I was sitting on the other side of the glass, looking at them with my mouth hanging open. What's remarkable is, a few years later I knew them all and was working with them on a daily business."

Do you feel that the way albums are recorded these days affects their quality in negative ways?

"I do hear stuff that is good, but I think the creative process has suffered dramatically. Not many records have the same vibe as records that were done back then, and it's because you're lacking a roomful of gifted musicians. Sitting in a room by yourself just isn't as rewarding.

"But I'm thrilled to be working. Last week I did three different projects, and everything was in real studios with real musicians. It was exhilarating. That used to be the daily routine, and now it's the exception to the rule."

Starting out, one of your biggest breaks was playing with James Taylor. How did that come about?

"It's one of those convoluted stories. In the late '60s, I was in a hard rock band called Wolfgang. We were managed by Bill Graham, whose real name was Wolfgang, so we named the band after him. The drummer, Bugs Pemberton, was English, and he had a friend named John Fishback. John owned Crystal Recording Studios over in England. One of John's oldest friends was James Taylor, who came to one of our rehearsals.

"James had just come back from England, where he did his first album for Apple. He was being managed and produced by Peter Asher. They were getting ready to do a gig at the Troubadour, and he mentioned to Peter that he'd heard this bass player he really liked. They called me - me and Russ Kunkel, the drummer - and we showed up, and Carole King was the piano player."

The hair's flying during a Toto show.

"I figured this would just be one gig, but Fire & Rain came out, and suddenly James is on the cover of Time magazine - he's like the second coming. Peter Asher asked me to do a tour. I was still in college, but I decided to go on the road. I walked out of college and never looked back."

What kind of bass were you playing at the time?

"A '62 Fender Jazz Bass. It was a total hippie bass that I'd carved peace signs into, and I had Frank Zappa's picture decoupaged on the back because I was a huge Mother's fan. I was using a little Univox amp with a single 15-inch speaker in it. That was my setup for the first couple of years."

You've played with so many top-name drummers over the years. Who are some of your favorites?

"Probably everybody - they all bring something different and unique. I just love playing with Russ Kunkel. We're almost like Siamese twins when we play together. I spent probably 12 solid years playing with Jeff Porcaro. Then there's Jim Keltner, Jim Gordon, Mike Baird, John Robinson - and Phil Collins. Phil is one of my favorites. There's so many. Playing with them has been such a blessing."

Why do you think you became such a 'first-call' bassist for sessions? Was it your playing, your attitude?

"Well, I have a real 'give a shit' attitude. I go to a session and listen to what the artist and producer want. I listen to playbacks, I throw out ideas, and I try to let people know that I'm engaged, and I want to be proud of me and proud of them when the date is over.

"You have to care about the music. I see guys all the time, they don't listen to playbacks, the minute a track is done they're on their cellphones and doing other things. That reflects on producers and artists - this guy doesn't give a shit."

Did you ever think that touring would hurt your session work, that the phone would stop ringing? Hal Blaine didn't want to tour for that reason.

"I couldn't function without it. If I was told I had to choose between being a studio or a live musician for the rest of my life, I'd choose live. A lot of guys I know are profoundly anal retentive; they love to sit in the studio and craft a part and aren't comfortable going out and throwing their asses on the line and saying, 'This is it!' You know, you get that one shot at playing something and making it great."

Was there ever a session that you had trouble on? Something about an artist or song that gave you problems?

"When Billy Cobham called me to do Spectrum, I arrived at Electric Lady Studios - there was Billy and Jan Hammer, and the beauty of it was Tommy Bolin. I knew Tommy from years ago. But when I listened to the heads on the stuff, I thought, Man, this is a handful. And playing with Billy is a handful. The whole stress of everything…

"There's been a few things, but not many. Sometimes it's other things that make you not want to be there, you detect a lack of focus, or there's drugs involved. Sometimes the artist just isn't prepared. For the most part, I haven't been confronted by anything too bad."

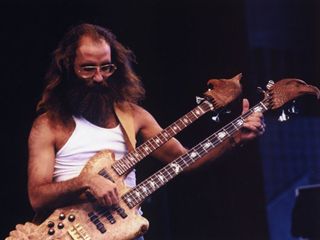

Sklar with his double neck 'eagle' bass in the '70s.

What are your go-to basses these days?

"I had a bass built in 1973 by John Carruthers. What happened was, I had a Precision neck - no body, but the neck was real nice - and we took a template from my '62 Jazz and reshaped the Precision neck into that.

"When Charvel first started, I went out there and saw a bunch of nice alder bodies, and I hung them on wires and tapped them until I found the one that really resonated. So I took that body to John and we made a bass out of it. It's kind of my Frankenstein.

"I've got first-generation EMG pickups on it. Also, I have two sets of Precision pickups, and I have them where Jazz pickups would've normally gone. But I reversed their position, which totally evens things out. In redoing the neck, we had to strip the frets off, and we ended up replacing them with mandolin wire, which is very small fret wire. We didn't know if it would work, but it turned out great. So that's been my main bass since about 1983.

"I did a signature model for Dingwall, which has become my main touring bass. You know, I see these guys on stage, and they have, like, 15 different basses, and I'm like, 'C'mon, just play.' I figured, if I had one note that required a five-string, I'll just bring out a five-string for the whole show. The Dingwall is what I used with Phil Collins and Lyle Lovett, and I used it on the James Taylor and Carole King reunion tour.

"A few years I got involved with Warwick. They had a bass called the Star Bass II, and we did a couple of them - fretted, fretless, an eight-string. It's really nice, kind of like a Hofner, but a little bit easier to play. I'm not a real gearhead, though."

So that means you don't go in for a lot of effects?

"No. I love an old Boss OC-2 Octave Divider. I have an old TC chorus-flanger. But I think most people like the purity of the bass, where you can build the sound out from it. When I get called in for a session, they like a nice clean bass sound."

What are you using for amps?

"I've been dealing with a company called Euphonic Audio out of New Jersey. I love their stuff. The amps are very hi-fi. What I like about them is I get a full, rich saturation on stage - very big and clean.

"One of the biggest lessons I've learned about playing gigs, especially in places with big PA systems, is this: don't play loud. Let the house guy mix you. I see some of these bands where the bassist has, like, three SVT rigs on stage. I'll go to the house mixer, and he's got the fader off - the bass player is blowing everybody away and can't be mixed."

Flippin' the bird during a photo shoot for a Dingwall bass ad.

What's the story behind that Eagle double neck bass you used to play?

"That's a pretty remarkable instrument. It was built by Steve Helgeson back in the '70s. The upper neck is a piccolo bass neck and the other is a standard neck. The body is a single block of burled birdseye maple. One of the fingerboards is ebony and the other is rosewood. One is inlayed with mother of pearl and the other is abalone.

"The bird headstocks actually come off. Steve was a falconer, so he carved these eagle heads out of walnut. The eyes in the heads are Mexican fire opals with LEDs behind them, so they actually light up.

"The problem with the bass was that it was really heavy. I had a case built for it, but it was cumbersome. It was built more as a beautiful piece of sculpture than a touring bass. I loaned it to the Boston Hard Rock for a number of years, and now it's hanging at the entrance to the Hard Rock Hotel in Tampa. I sold it to them. It's probably the most beautiful instrument I've ever owned."

What advice do you have for young players, people who want to play sessions?

"Like I said before, it's really a different world today. There's work going on, but I see the same faces that I have for years. It's almost as if there are no young people getting called to go in. I was talking to an engineer the other day, who told me, 'Yeah, we had a young band in here the other day. They had no clue how to get a sound or play in time.'

"There's an expectation from young players that Pro Tools will cover all of their inadequacies. I remember a time when you couldn't have inadequacies - you either cut it or you didn't.

"If I had any real advice, it would be to play with people. Go more in the band direction. You might get a chance to go into the studio, where people might say, 'Hey, that guy sounds good. Let's track him down, let's use him on something.' That's how it happens."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

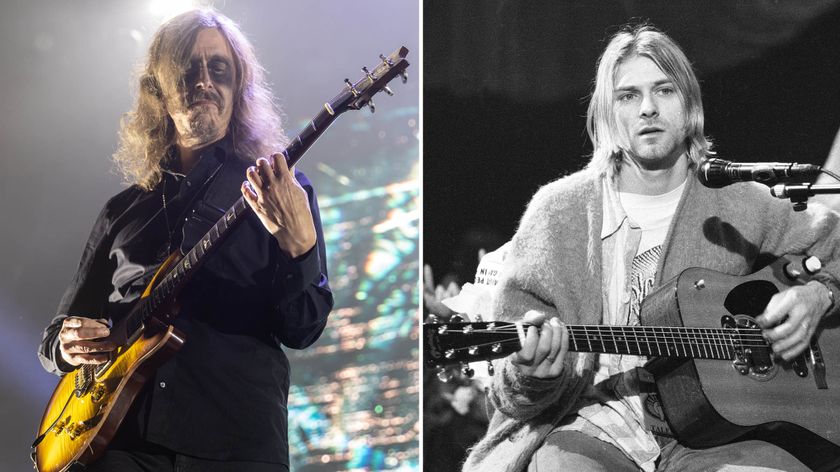

“I’m a Nirvana fan, but it was just a regular guitar to me”: Opeth frontman Mikael Åkerfeldt left unimpressed by Kurt Cobain’s “haunted” Martin acoustic

“Boy, he’s a weird guy. He’s got one orange sneaker, one red sneaker”: Gene Simmons on Ace Frehley’s memorable audition for Kiss

Most Popular