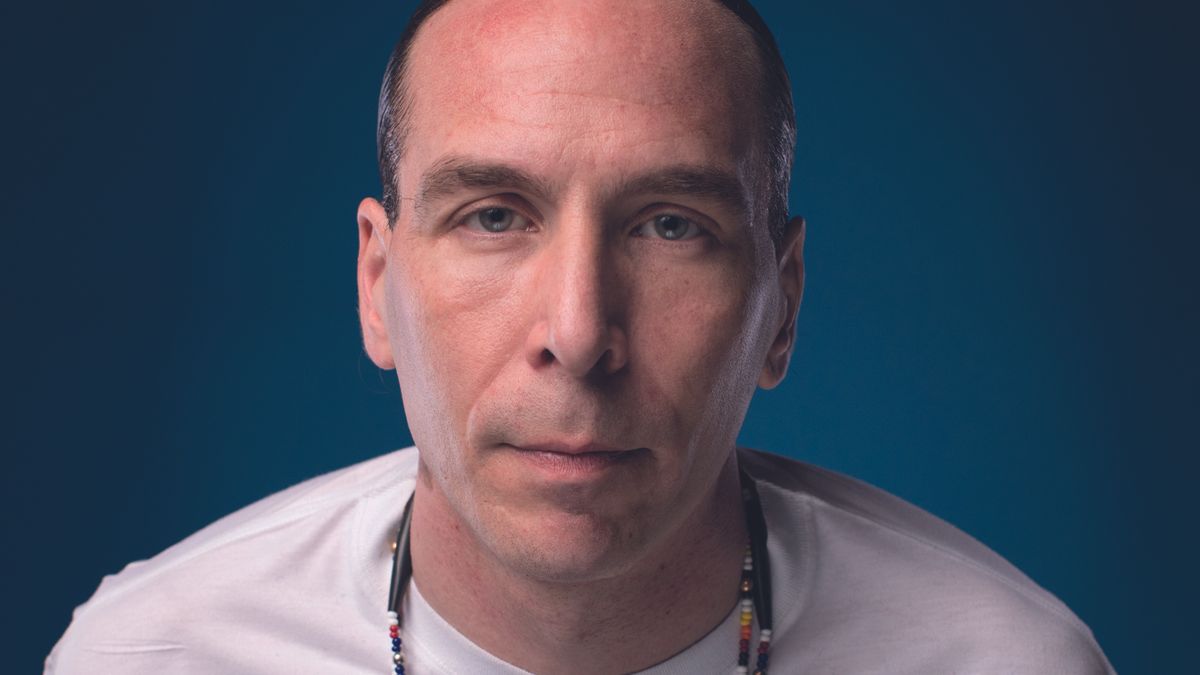

Audio engineer David Strickland: "Hip-hop is indigenous culture in a modern form"

“There’ll be artists that sneak by despite not having the quality, but there could be all kinds of reasons for that"

Mentored by production legend Noel ‘Gadget’ Campbell, Grammy and JUNO award-winning audio engineer and producer David Strickland has been a crucial denominator behind the success of numerous groundbreaking acts in Toronto.

Over the past two decades he’s elevated the work of seminal hip-hop and R&B artists like Pete Rock, EPMD, Method Man and Sade, and was mixing assistant to Drake’s chart-topping debut Thank Me Later.

Born and raised in Ontario, Strickland started as a b-boy, before evolving into the roles of DJ, MC, engineer and producer. Embracing his ancestral origins, Strickland has long sought to strengthen ties between hip-hop and native music traditions by bringing artists together.

Now, 25 years into his career, he’s ready to sit in the artist’s chair with his latest album project Spirit of Hip Hop, showcasing indigenous MCs alongside his unique blend of mainstream rap rhythms.

You began as a b-boy, which I guess is a terminology that’s lost on young people today. What did that expression mean to you?

“I was an athlete, so maybe it was just another form of expression. Hip-hop is indigenous culture in a modern form and it was the first time I’d tapped into that sort of thing. The ties between hip-hop and native music traditions show that the DJs are like the drummers, the MCs in hip-hop are the storytellers, the b-boys are the dancers and the graffiti writers the sand painters.”

Has modern hip-hop moved too far from the genre’s origins?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Sure, but that’s always happened. It’s always evolved and always will. I love to make music and work with artists and there’s always going to be good music, bad music and lazy artists. There’s an argument about authenticity and all that stuff, but if you’re looking for that type of sound it’s still being made.

"With the accessibility we have nowadays it’s way easier to find that music than when I was younger, so if you can’t find what you’re looking for you’re not looking hard enough. People forget all the sub-genres of hip-hop like hip-house, which was great. I don’t know what happened, maybe they call it something else now, but there’s going to be sub-genres and that’s OK, that’s what happens.

"Good music spreads, evolves and changes – you can go where you want with it.”

Was the plan to become an engineer/mixer and work your way up to a producer role?

“I got into DJing and MCing, which led me into engineering and producing. I wanted to record but I didn’t realistically think I’d be successful at it. I had a good voice so I studied radio broadcasting thinking I could get into radio and make a decent living at that. That was my plan until I really got into engineering and thought, 'OK, I kind of like this'.

"I learned about gear from spending time in studios but was pretty apt at technology anyway. I did go to engineering school, which led me to my mentor Noel Campbell who taught me a lot of stuff that a school couldn’t teach. It was a labour of love - you can go to school, but to get really good you gotta put in the time and work, so for a lot of the time I coached myself.”

And gear wasn’t as accessible in those days as it is now, presumably?

“Correct. You could sequence on a computer but you had to buy a lot more expensive gear if you wanted to record. Studios were still using tape up until almost 2000 and that was expensive. Technology has changed a lot, so you really had to go out of your way to get into it. Not everybody was into making music like they are now where the whole process is done in home studios and there are even apps on your phone so you can make a beat.”

Do you feel there’s an element of quality control missing with home studio recording?

“There’ll be artists that sneak by despite not having the quality, but there could be all kinds of reasons for that - maybe nobody taught them, so I’m not trying to be a player here. Some quality control’s missing but there are still a lot of professionals. Somebody made an app so you could build your own car at home, so technology has changed the game for us all. Car companies are feeling it but they still make better cars.”

Have you noticed a lot of variability in the records you listen to these days?

“I have noticed that. It depends where it’s coming from. See it’s not just the technology that’s changed, the way we play our music has changed. I could go press some records and put them in a store but couldn’t put them on a platform that gives them access to everybody in a week. People are becoming stars because of that accessibility. Back in the day it was good to have that regulation, but what were we missing out on? Think of all the people we wouldn’t have heard from.”

You touched on how people play music. As a producer yourself, have you had to adapt?

“It is what it is. Sometimes I joke at artists when I send them a mix and say, wait, are you listening to this on a laptop? Sometimes I’ll listen to mixes on computer speakers, but a good engineer will also listen to a mix on shitty speakers because we know that people aren’t going to listen to them on a studio system and you have to consider that in your mix. If it sounds good on computer speakers, a lot of times it will sound really great on a nice system.

"One thing I do know is when I was at high school I had ear buds for my Sony Walkman and only a few other people did - now everywhere I look everybody’s got ear buds. We’re always going to have professionals, so hopefully that doesn’t die out, but the evolution has been so fast that you have to wonder where it’s all going.”

“It was about survival. Doing music full-time and getting paid is hard enough”

Where do you think it’s going?

“I think the artist will be eliminated. You’ll make a beat, put the lyrics in and pick the type of voice and then you don’t need the artist. That’s going to be a thing just like in TV and movies where the actor will be eliminated. Name a famous actor that’s passed and they’ll make a whole new movie with them.

"These are the things that are probably coming next because where else can we go? Everything has a time limit, and maybe that’s 20 or 30 years from now.

"The other thing that could happen is that people won’t like that because we’ll miss the human element of it. The technology might seem too manufactured and we won’t stumble on the mistakes that become great. How are you going to tell if something’s good if nothing’s bad?”

I think the artist will be eliminated. You’ll make a beat, put the lyrics in and pick the type of voice and then you don’t need the artist.

How long did it take to get to a position where artists took you seriously as a producer?

“I studied engineering and a lot of artists started to rely on me because I was dependable. I was always around a lot of artists and started working with a lot of people. There are guidelines, boundaries and studio etiquette. At first I was there as an engineer, not as a producer, and I wouldn’t really ever cross those lines.

"Later on, I wanted to get more into the production side of things so I started submitting more music to artists whether I was working with them or not. So I was always producing but wasn’t sharing much as I enjoy engineering and love mixing. Not everybody can do it, but it really encompasses you.”

Was it more about making connections than having a production CV?

“It was more about survival. My life was pretty hectic, so it was just about getting to the next thing. Doing music full-time and getting paid is hard enough. I had a day job and did music at night and eventually one transcended to the other, but I had to work hard to maintain that and producing is another animal because you’ve got to have the luxury of being able to sit down and write music – then you have to get good at it! That takes time and eventually I had opportunities arise and I’m very grateful for that, but it wasn’t an overnight thing.”

From all the artists you’ve worked with, which ones stand out and for what reasons?

“That’s a tough one; it’s not a name thing. I‘m a visual artist as well - I paint, but I didn’t start painting to sell them. When I did sell them because I could do with the money, it was hard to let go.

"When you produce with somebody, it’s always special because you’re making something that’s healing. When you’ve worked on a big record that touches many people it’s so special to see; just like it’s special for me to see my painting go into a big gallery and have people touched by that. That kind of thing blows me away.

"I’ve done some productions that might have been raw and not the biggest song, but I probably still had a great time doing them and the experience of being able to do that is a gift so I can’t discount it.”

Do you feel a sense of responsibility to create successful records or is that all down to the marketing aspect?

“I just do my thing and let others figure out whether something’s radio-friendly. I don’t even think about that when making music. Half the battle is just making it; I don’t even know what it is until it’s done. At the end of the day, the world’s going to tell you. People follow trends and that’s OK; some people set trends, but how do they even know that? Some of the hardest hip-hop has ended up being a radio or pop record because it got that big. It’s the people that make it popular.”

What’s your approach to working with artists?

“I just did a record with somebody who has a ‘sound’, so I told them it needs to sound like them. You can’t just give them any old beat - I mean you could, but if you’re a good producer you have to ask yourself who you’re working with.

"For example, if it’s Bon Jovi it doesn’t have to sound like every other Bon Jovi record, but they do have a sound. If you want to make an AC/DC record, they have a sound and there’s room within that to move around. You can push boundaries, modernise and go other places, and I’m all for that, but you have to keep in mind the perspective of who you’re working with.”

That implies you have to do a bit of research on an artist before working with them?

“I tend to do that. I like listening to music and stay up on stuff anyway, but if I don’t know them I’ll go find out. I love discovering new stuff; it’s beautiful to see because sometimes you think to yourself, 'damn why didn’t I think of that'? Depending on the artist, once you start working with them you get to see if their skillset and what they can do and start pushing their boundaries. R&B singers or anyone who has a powerful voice, especially rappers who can flow, are good for that and really fun to work with as long as they’re not afraid to listen and try new things.”

Do you have to be careful about forcing your opinion on them?

“If you’re in the studio with someone like Prince, or someone of that stature, it can be intimidating, but I’m not afraid to speak my mind. A lot of times people like that and a lot times people kiss ass. I don’t want to upset anybody, I just wanna be honest about how I feel. I’m not always right and sometimes I get put in check, but that’s how you learn too. You’ve just got to be respectful.

"I worked on something last week that came out beyond my wildest dreams - I couldn’t have asked for it to be any more perfect - but you get the opposite too when you’ve got a mess and have to clean it up.”

You’re a big fan of drum programming and making custom drum kits. Do you distinguish between hardware and software or are they both interchangeable?

“I used to be stuck in that hardware-based way of doing things, but around 2005-06 the software started coming and things started evolving in terms of production. If you want to stay in this game you’ve got to continually keep your skillset up and keep learning - you can’t just think you’re the best and keep doing things the same way.

"I had to retool so I use a lot of software now, but use both depending on what I’m doing. A lot of times I’ll record instruments and use live players too. As an engineer, I’ve done rock and country records and that’s a different process when it comes to making music. I’m not afraid to try things, like record a guitar, chopping it up and rebuilding a song using software in a hip-hop way.

"At the end of the day, you’re doing this because you love it and it’s fun. Some people think I’m being grumpy in the studio and I laugh and say, 'don’t tell anybody but I’m secretly having fun'.”

Do you have a minimalist setup based on a few choice pieces of gear?

“I used to have tons of gear and I’ve had big studios but now I have a minimal personal setup. There’s a lot of stuff in my boxes now because I can put a whole rack in my computer.

"I also have access to bigger studios in New York or Toronto where we have a lot of gear. For example, with Death Squad we have a certain amount of equipment based in one setup, then I have my own private studio and in New York I have another studio with SSLs, tape machines, old-school gear and whatever new technologies I need to use.

"When I first got into this I had my own studio but always had keys to six or seven big studios around the city where I could do sessions and work on different projects. I was always lucky enough to have that whether I owned a studio or not. It’s also a space thing - otherwise you have so much gear it becomes overwhelming. Who’s got time for all that [laughs]?”

Do you agree that limitations can be better?

“They are better. I know what I need and know a lot more now. I’ve learned so much from working with other people, but I also forget because I’m so lost in it.

"I have these conversations with people all the time where I don’t think I’m anybody; I’m just a guy trying to get through and survive. I’m nobody special and that’s how I look at it, but some people don’t perceive me like that - they see that I’ve done all this stuff and think I’m a legend and all that. That’s not what it’s about for me. I’m just trying to make good music and if people are into it then it makes me happy.”

I’m guessing your new single, Turtle Island, is more about conveying a political message, not trying to emulate the artists you produce?

“I’m trying to tell a story from the artistic, political and environmental perspective. Outside of my community, people don’t get to hear from indigenous artists and a lot of times they don’t work with the more mainstream artists. I’m trying to bring that together and show what can happen when you do that.

"There’s a lot of stuff going on over here right now. Canada just invaded a sovereign nation, on lands that have been lived on for 10,000 years, so the people are uprising and we’ve been defending that. I didn’t write this song last week - it’s something that’s been happening for a while.”

“I didn’t write Turtle Island last week – it’s something that’s been happening for a while”

There’s an album, too, Spirit of Hip Hop. What’s it like on the artist’s side of the fence?

“I’ve learned a lot about how much I’ve grown, how much I can push myself and what I’m capable of. Usually I’ll engineer or produce for somebody, give them their stuff and say see you next time, but this is my thing now. When I made Turtle Island I thought ‘this is good’ but I don’t have someone like me to go to and now I’m the one being judged. It’ll be interesting to see the response and get to have the excitement that the artists have, that I’ve been missing out on.”

It sounds like a great combination of past and future – old-school elements and sampling, but modernised?

“There’s no sampling, it just sounds like that. Sometimes I’ll play stuff and resample it so it sounds like a sample. If you hear the indigenous drummers in the song, they’re all recorded live but I mixed it down and sampled it. I do that all the time - take something and move it around, because you can do so much stuff with the technology. Before you’d sample and loop it or make a kick or snare - typical things, but now you can completely reshape the sound. It’s interesting you said that because there are minimal samples on the whole album and a lot of cheating, so it’s good to hear I pulled that off.”

Find out more on David Strickland's website. Spirit Of Hip Hop is out now.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

“My love letter to a vanished era that shaped not just my career but my identity”: Mark Ronson’s new memoir lifts the lid on his DJing career in '90s New York

“I’d be running from the studio to other speakers in the house, basically going insane trying to get mixes to sound correct”: Ezra Collective’s Joe Armon-Jones on why he created his Aquarii Studios and his dub-influenced mixing technique