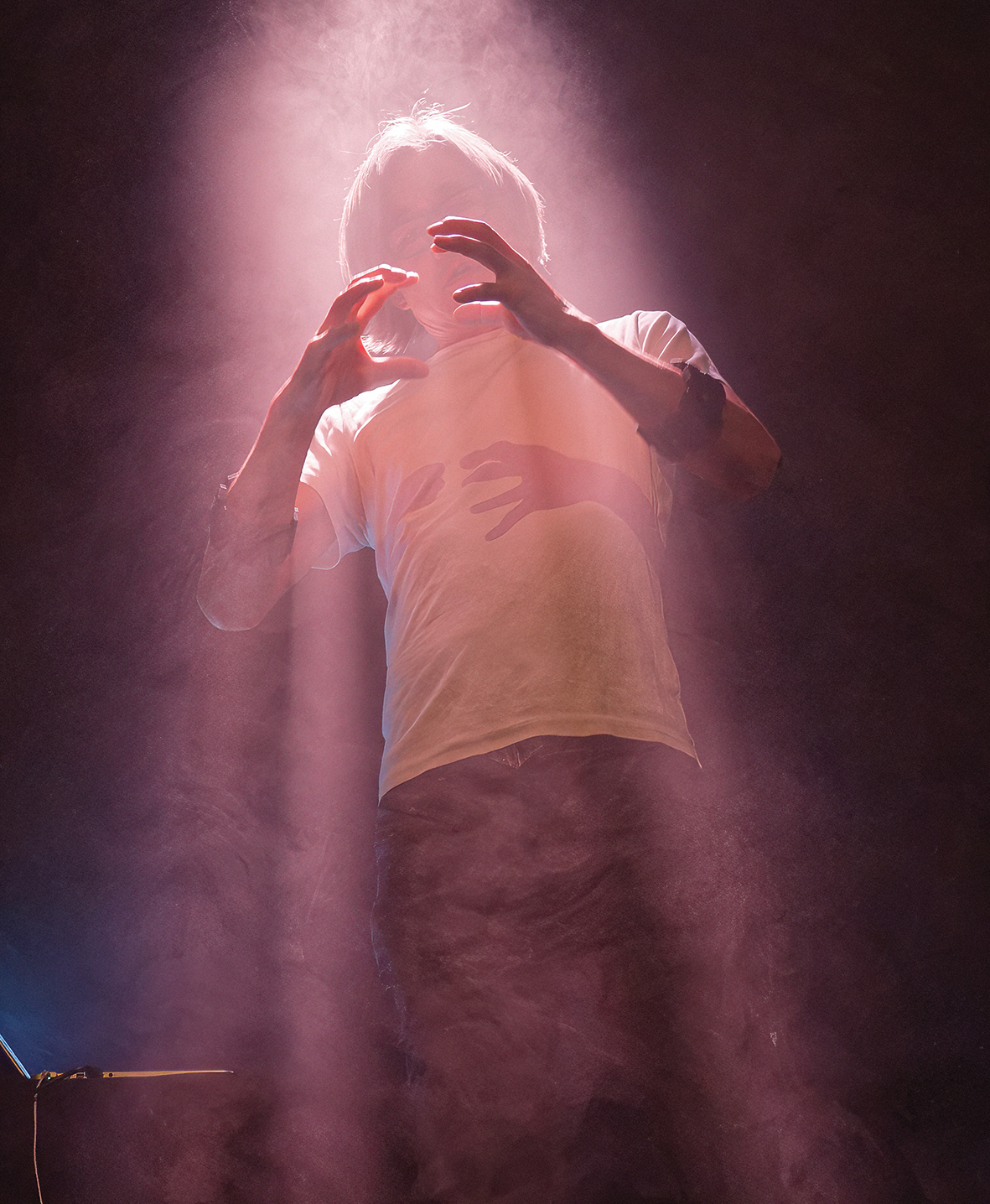

Atau Tanaka: "I didn’t want to hide behind racks or synths - I wanted electronic music to become a live medium"

Creating electronic music using the movement of his own body with custom-built software, Atau Tanaka takes the ideas of software control and performance to a completely new level

A typical electronic music setup can cover anything from a simple MIDI keyboard with a laptop and studio headphones, to a huge modular rig.

But none of this applies for Atau Tanaka, a Japanese-American artist who appears to be pulling sounds out of thin air through arm movements, hand gestures, and muscle tension. We talked to Atau about his setup, his extensive history with expressive electronic music, and what’s coming next for music technology.

“My musical education was quite traditional. I started off playing the piano as a child, but I got sick of playing classical music in my late teens,” Tanaka tells us when we ask him to tell us a bit about his musical upbringing.

“I tried to switch to jazz, but I didn’t have the ear for it – so I picked up the electric guitar! In my university days I played in free improv bands – there was a club in NYC called the Knitting Factory, and John Zorn played there, and Fred Frith, and I’d see gigs of theirs, and met them eventually.

“Then I discovered the electronic music studio at Harvard, where I was doing my university studies, and a composer there, Ivan Tcherepnin, was my mentor. And this was the early ’80s, so we had open reel tape machines, spliced up tape, we had a Buchla 200 synth, a Serge modular, and I got into analogue electronic music.”

Atau was quick to embrace the possibilities of MIDI and digital audio. “In 1984, the Mac 128k came out, and MIDI synths came out. I bought a Roland JX-3P – their first synth with MIDI. And I was always interested in ultimate controllers, you know, I was exploring the early MIDI guitar systems. That search for controllers is a theme right through until today.”

“The laptop enabled me to take it [electronic music] on tour. In the early ’90s, the Apple PowerBook didn’t do audio – it was just MIDI, and Max was MIDI only. It would take MIDI input from Bio Muse – that was the muscle interface. And then I had a rack with a Yamaha TG77, a Korg Wavestation, and Kurzweil K2000, and I was trying to make sounds from those in a way that you couldn’t get from a keyboard input.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“When the PowerPC chip came out in the mid ’90s, you could do audio on the laptop, and Max took on MSP functions, and that’s when I was able to stop using the rack, because I was carrying it on trains all around Europe on tour.”

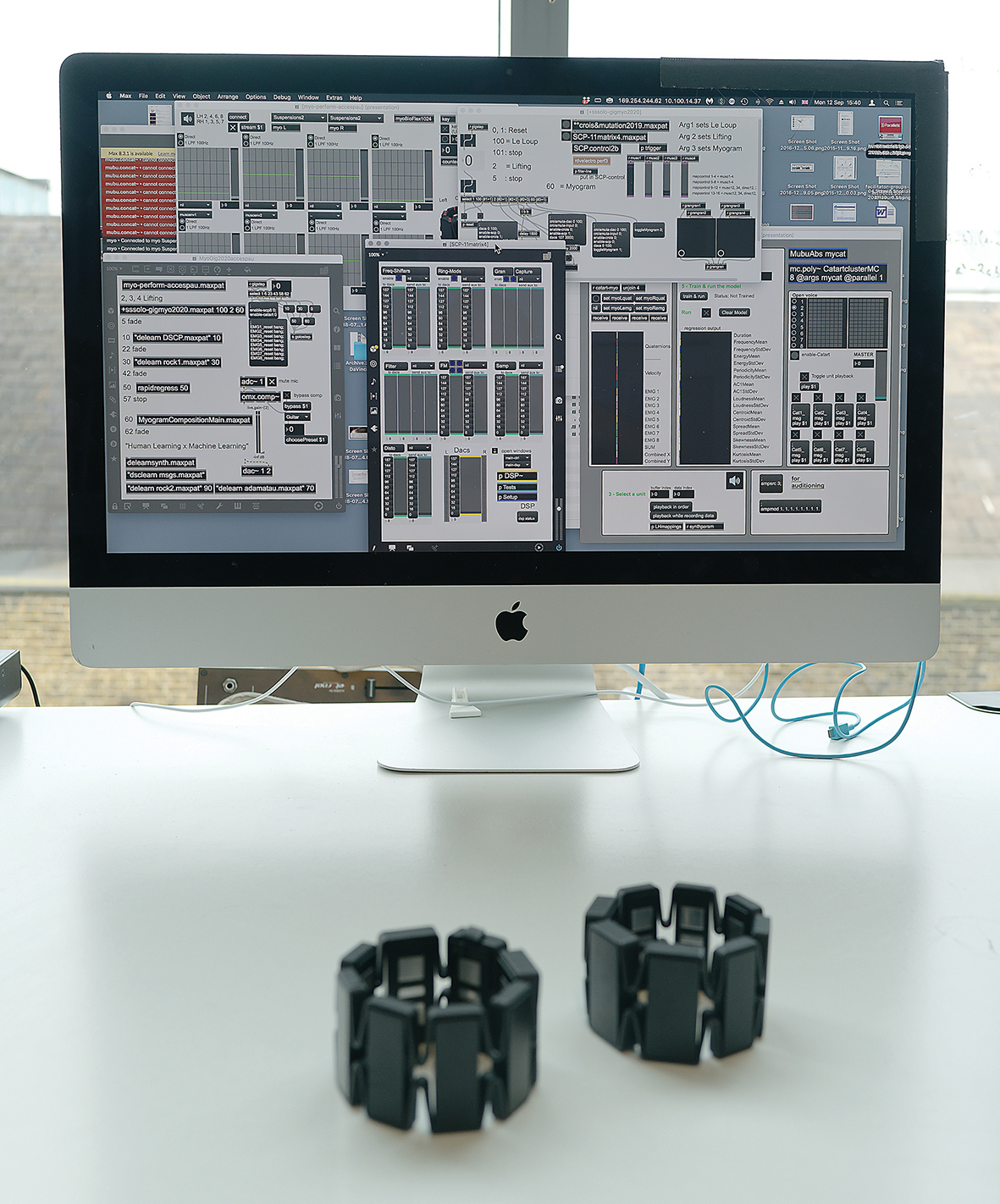

Atau continues to employ alternative interfaces: “I use systems that capture body movement, and the physiology of the body. I’ve been working with muscle systems since my days at the CCRMA at Stanford, where I was doing my PhD. Most recently, I’ve been performing with a device called the Myo, made by Thalmic Labs – a bracelet that picks up muscle tension.

“Unfortunately that’s discontinued, so we’re working on a new system called the EAVI board. Other than the Myo, my setup is a classic laptop musician setup, based on a MacBook Pro, still with Max for gigs, although I’ve got Ableton Live and Logic Pro X on there, and I produce the final tracks in a DAW for recorded release.”

In this environment of abstract, digital, music, performed without traditional interfaces, does ‘classical’ western music theory still have a place? “I like the word ‘comprovisation’,” Tanaka replies. “It’s a hybrid between composition and improvisation. If you take classical music, Mozart was a great improviser, Bach was a great improviser. And even if you play note for note, a Mozart sonata, or Bach partita, there’s a huge amount of interpretation, and there’s a musical energy that comes through. And I’m very interested in that.”

Techno music was born from the interface of those Roland drum and bass machines – if somebody’s using a custom control surface with custom software, does the music have to reflect that?

“That’s called ‘idiomatic’ music – when you go to violin, you compose for violin, if you’ve got a flute, you compose flute music. With digital music you can play any sound from a keyboard, but I was interested in getting back to the instrument, and what is specific for that instrument, So yes, I make my own Max patches, I design my own musical instruments. And I am the one who goes on stage to perform.”

Unlike classical music, Tanaka’s work must be challenging to share between musicians – there’s no common scoring language, or equipment. “It’s like an independent film, where you get the script and direction and the producing all done by one filmmaker,” he notes.

“At the same time, I am a composer who knows how to write a score and transmit a piece to another performer, and that’s been done with my piano piece, recorded on the Meta Gesture Music album by Sarah Nichols, a British pianist. The piece exists as a score, and it’s also got the Max software, all in a package, almost like a product with an installer with instructions, and the Myo interface. So Tricia Dawn Williams in Malta and Kathleen Supove in NYC play it.

“And we’ve got an Italian pianist in Antwerp, Giusy Caruso – she’s the first pianist to get the whole thing running without me having to come help her. It’s an important thing, I think, for us; electronic musicians have to continue those traditions of transmitting the music, through scores, but also by making the technologies that are available.”

More about Myo

If you try to search online for Myo armbands or their creator, Canadian company Thalmic Labs, you’ll be sadly disappointed. In 2018 Thalmic rebranded as North, and launched a pair of ‘smart spectacles’ called Focals. North was subsequently acquired by Google, who soon after shut down North completely. Apparently there are still Myo applications available, so if you can track down a set, you might be in luck, but that’s strictly at your own risk.

But what can you do with Myo, if you can get some? It’s based around a system of recognising a few basic gestures – wave left, wave right, spread fingers, fist, and thumb to little finger. It does this by reading muscle activity in your forearm, and combining this with your arm’s orientation. It’s been used in many situations, from controlling media players, to gaming, controlling the Sphero robotic ball, piloting drones, and even interacting with prosthetic limbs.

The setup is very clean, with just one or two armbands, and a bluetooth connection to a computer. There are no external power packs or connecting cables (they have internal batteries that are recharged via USB). We would like to think that somebody will pick up this technology and develop it further. Fingers crossed.

Minimal performances

When Atau performs, he has nothing on stage, just the MacBook Pro off on one side, and one footswitch to change presets. “It is theatrical, it is intense, so I don’t think I need to add anything to show off, and I’d rather not add anything artificial. I’m going for a stripped down, minimalist presentation, so that whatever you experience, is real.

When Atau performs, he has nothing on stage, just the MacBook Pro off on one side, and one footswitch to change presets

“I wanted electronic music to become a live medium because I was an instrumentalist. That’s why I was interested in alternate controllers the whole time, MIDI systems. You could be Jean-Michel Jarre and have a whole bank of synths around you, and make a whole orchestra’s worth of music, but as an instrumentalist, I wanted to play one human being’s worth of instrumental music! I didn’t want to hide behind racks or synths, and I want to put the body first.

“With laptop music performances, you can’t tell necessarily what people are doing. You can do tiny things by turning a knob or clicking the mouse to produce huge changes in the sound, but it’s not that legible to the audience. The great thing about electric guitar is you’ve got overdrive, distortion, saturation, and you can keep pushing the limit. With digital, especially early digital, if you filled up the binary bandwidth, that was it. I just couldn’t push it any further.”

Playing solo gigs is one thing, but does Atau find that something as individual as this works in group situations?

“I perform in bands and in different one-off collaborations,” he replies, “and it works in different ways for each of them. We had a band called Sensorband that toured for 10 years, and in the ’90s had a second band called S.S.S. And I’ve played in the French improvised scene quite a bit, some with filmmakers called Metamkine, and one-off collaborations, like with poet Jasmina Bolfek-Radovani.

“Playing in groups is a good testament to what I do, because computers are programmable, but then once you’ve got it programmed, it does what it does – how much freedom do you have within that? If it’s a band setting, you can get to know them, and so then your musical identity has a place that you can really work on; in a one-off collaboration, you have a lot less time, and on the spot you have to be able to play it in a way that can be adapted to the content of the musical context.”

Atau has a minimal-looking setup, but there’s a fair bit of technology at work. How and why does he think the average person can explore this for themselves?

"I want to open up people’s sonic awareness. I don’t expect everyone to do what I do, but I want it to be an example"

“It’s opening up a new sonic palette – synthesisers allow any kind of sound to be made, but we’re sometimes limited by our imaginations. I want to open up people’s sonic awareness. I don’t expect everyone to do what I do, but I want it to be an example, to point out the possibility of doing something meaningful with new technologies. I teach in a university, and I practice what I preach, through releasing and performing my music.

“You know, the mobile phone has very sophisticated sensors? How many people actually use them to make weird electronic music? We need examples of what’s possible, what’s musically interesting and meaningful, but it doesn’t have to be scary, and I think learning music has always been scary. And that’s one of the things that I felt was always off-putting about trying to learn a traditional instrument.

“Electronic music was supposed to make that more accessible, but if it’s just presets in GarageBand, and you’ve got a track instantly, you don’t understand what you’ve done. I’m looking for something in between the two, where it’s engaging, it’s accessible, but you start to learn about sound. If it’s a route in to introducing music, as an activity, that is a real great, noble mission, you know, because there’s less and less music taught in schools. And I think to get it out of the computer, the idea of a ‘post-computer music’ is interesting.

“Young people aren’t interested in computers actually – the iPad or the mobile phone can hook their interest and makes it relevant. But then we have to go the next step, that if they just get locked into another app that keeps them on the screen of their phone, and you can’t tell whether they’re texting, playing a game or making music, then having another device that talks to the app, whether it’s knobs or a keyboard, or a gesture controller, makes music embodied again, and that’s really important.”

Get more expressive

“Although sometimes it seems like the electronic music world is full of pads and keys, there are many ways we can break that mould and use more expressive tools, whether instead of or alongside our familiar controllers.

The electronic music world is full of pads and keys, but there are so many ways we can break that mould

“Any keyboard with pitch and mod wheels is a start – if your software lets you assign those to different parameters in your virtual instruments, then you’re off. Some keyboards have joysticks, and touch strips; Ableton’s Push is a very conservative device in many ways, but it has a touch strip that can be configured to perform different tasks.

“MPE (MIDI Polyphonic Expression) is becoming more mainstream, and with a suitable controller, this adds extra responsiveness. Then there are mobile apps, using touch interfaces to add more customisable flexibility, and don’t forget, those devices often have accelerometers, that apps can access to send control messages according to the orientation of the device.

“If you like game controllers, there are several applications which will convert incoming controller messages to MIDI commands or keyboard shortcuts that music software can use, and we still get a thrill from using the Nintendo Wii Remote Control to trigger and manipulate sounds in Ableton Live’s Operator synth.”

Predicting tech

And then of course we’re wondering what’s next? “More and more use of AI technologies. I use neural networks – instead of manually mapping input to the sound parameter, a neural network can create very sophisticated mappings for you. All you have to do is give it some examples.

“So that’s very rich, and there’s a software called Wekinator, that’s super-interesting, that allows you to do that with MIDI. And then Google’s Magenta project publishes a lot of AI code, and has some stuff for sound synthesis. People are starting to work more and more with using AI generated sounds, or to create infinitely varied remixes.

I’m working with a neuroscientist, so hopefully next year I’ll be performing with brainwaves and muscle

“I’m also working with a neuroscientist, Stephen Whitmarsh, so hopefully next year I’ll be performing with brainwaves and muscle. And I’m kind of tired of having a laptop on stage with me all the time, even if it’s off to the side. I’m interested in post-laptop music, and the Raspberry Pi is an obvious interesting avenue.

“That’s one reason I’m also interested in working with Martin Klang on Rebel Technology hardware. His OWL framework gets a lot of those languages like Pure Data, and FAUST running on pedal boards. With embedded computer music, different instruments do different things, and everything doesn’t even have to be in one computer. They’re like analogue modular synths, dedicated boxes, but reprogrammable.”

Find out more about Atau Tanaka's work on his website.

Further listening

1. Atau Tanaka - Live At Iklectik

“This is a live recording made at Iklectik in London, using my system with the Myo and Max. It also exists as a video, but we got a really high quality recording of that gig, and it was a real pleasure to be able to release it on Superpang which is a great label – I feel like the audio really does come to life on that release.”

2. Various Artists - Meta Gesture Music

This anthology features musicians who crossed paths during Meta Gesture Music, a European research project which ran between 2012–17, exploring gesture in musical performance. The compilation features Atau Tanaka, composer/pianist Sarah Nicolls, Tom Richards performing on his Mini-Oramics light-sound instrument, Kaffe Matthews making music with sharks in the sea, xname amplifying electromagnetic fields, Laetitia Sonami, Leafcutter John, Renick Bell and Steph Horak, Dane Law, and Ewa Justka.

3. Laetitia Sonami - The Lady's Glove

Laetitia Sonami is a French artist who resides in San Francisco, and appears on the Meta Gesture compilation mentioned above. She created the Lady’s Glove, a wearable controller which allows movement to shape sound and visuals.

She also created the Spring Spyre, which can be seen in the photo below. This is a circular metal ring which uses three pickups and thin metal springs to generate audio signals. The instrument uses machine learning to control sound synthesis in real-time and makes use of Rebecca Fiebrink’s Wekinator software

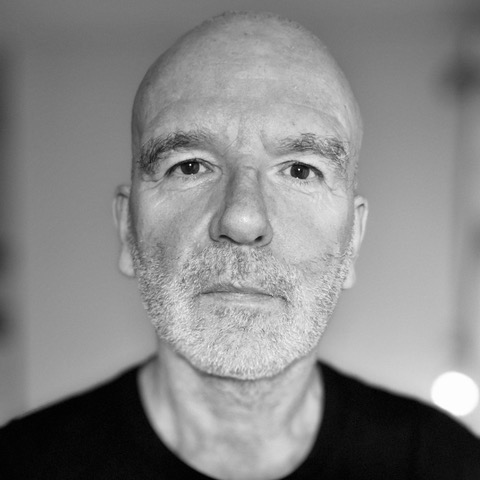

Martin Delaney was one of the UK’s first Ableton Certified Trainers. He’s taught Ableton Live (and Logic Pro) to every type of student, ranging from school kids to psychiatric patients to DJs and composers. In 2004 he designed the Kenton Killamix Mini MIDI controller, which has been used by Underworld, Carl Craig, and others. He’s written four books and many magazine reviews, tutorials, and interviews, on the subject of music technology. Martin has his own ambient music project, and plays bass for The Witch Of Brussels.