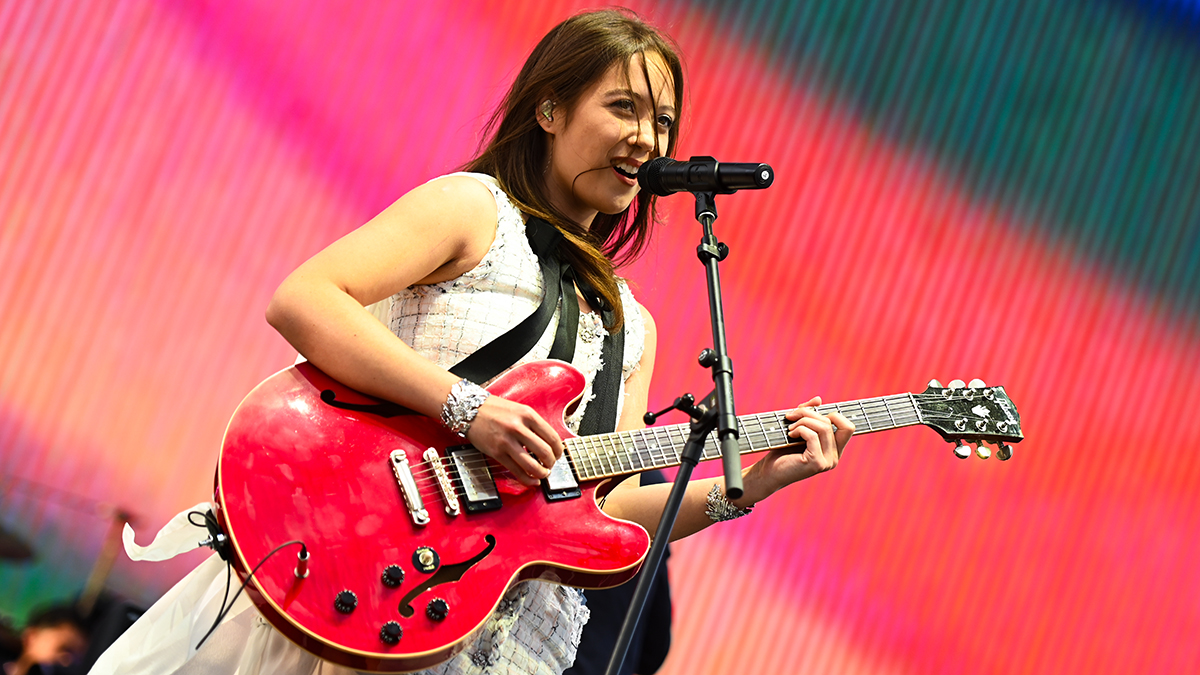

Bee Gees producer Albhy Galuten on creating the first ever drum loop: "We found two bars in Night Fever that felt really good, copied it to tape, spliced it together and ran a huge loop over the mic stands and across the studio"

With 18 number one singles and 100,000,000 copies sold, Grammy-winning producer Albhy Galuten continues to operate at the cutting edge of music today

Musician, arranger, producer, futurist and hi-tech evangelist Albhy Galuten has spent decades at the epicentre of music’s shifting planes, having been literally in the room while history was made on too many occasions to count.

His production work alongside Barry Gibb and Karl Richardson for the Bee Gees, Barbara Streisand, Diana Ross, Dionne Warwick and more defined the on-trend sound of the late seventies and set the tone for the pop/dance decades to come.

Galuten, alongside Richardson, pushed the tech of the time to the limits, including the creation of the first ever drum loop – a hastily rigged loop of half-inch tape that played the perfect beat on global smash Stayin’ Alive to replace their called-away drummer. The rest, as they say, is history.

Now making his mark with software technology company Intertrust among others, Galuten is still opening creative avenues, creating content delivery standards that aim to pave the way to a better, easier and safer digital future.

Before we take a step back, let’s look forwards. As a futurist I’m keen to get your take on the hot topic of AI. What’s your take on the role of AI in music?

"I’m balanced. I’m not pro-AI or anti-AI. I guess when I was a record producer I was pro-drum loops because we created the first drum loop. And when the drummer [Dennis Bryon] came back from visiting his father who was ill, we were like oh shit. This feels too good… This is amazing."

How did Dennis Bryan feel when he came back and he’d been replaced with a drum loop?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"He was ambivalent. He came back and we said 'Of course, you’ll replace the drums' and we played him the track. But that loop felt amazing. And he was like 'I’m not replacing this, it feels too great.' He did overdubs. He was still in the band and he still got his royalties but he knew.

We found these two bars in Night Fever that felt really good, so we copied it onto a half-inch tape and spliced it together and spread it out across the room, running a huge loop of tape across the mic stands

"One of my proudest moments was when I was reading Jeff Porcaro’s book. We had Jeff [Toto’s legendary drummer and session man] out and he made some loops for us back in Miami. Then, after that he went out to LA and created his own loops with [percussionist] Lenny Castro. And Africa is a drum loop! That’s a direct result of Jeff learning about our loops and thinking 'Wow, this is a cool thing!' And Africa feels great as a result."

What’s the story? Why create a drum loop in the first place?

"Dennis, our drummer, was called away during the sessions and we wanted to keep working so Barry and I sat around listening to the drums, going through the song and we found these two bars in Night Fever that felt really, really good, so we copied it onto a half-inch tape and we spliced it together and spread it out across the room, running a huge loop of tape across the mic stands, across the studio."

I’m intrigued by those early sessions with the Bee Gee at Château d'Hérouville. You were actually there when the Bee Gees ‘went disco’. Looking back it seems such an odd thing for them to do. Such a complete change of style – and one that would be hugely successful for them – but at the time…

"We didn’t listen to disco. We didn’t think we were a disco band. We thought we were an R’n’B band. Barry and I connected because we loved Stax and Motown. We had the same sort of history."

The story goes that Robert Stigwood turned up with the script for Saturday Night Fever and – boom – you make five genre-defining disco tracks after that?

"When they made those songs they had never read the script. They had never read the Nik Cohn article in the New York Times. They just knew that it was about people in a club in New York, dancing. I played in discos when I was in highschool in the ‘60s – they called it a disco. Disco just means dancing. We liked R’n’B music so we were just making groove records."

So it wasn’t like you had other disco records on hand and you were “we’ve got to do this”?

"No, we had no idea."

And as far as then creating a style that was subsequently copied…

"We were just making a record that we thought sounded good. I suppose Barry had probably heard some dance records but what Barry was interested in was the top 20. That was why he was so good at resonating with the collective unconscious of the world. Back then everybody watched the same news, everybody heard the same stories, so if you got it right you could really blow up."

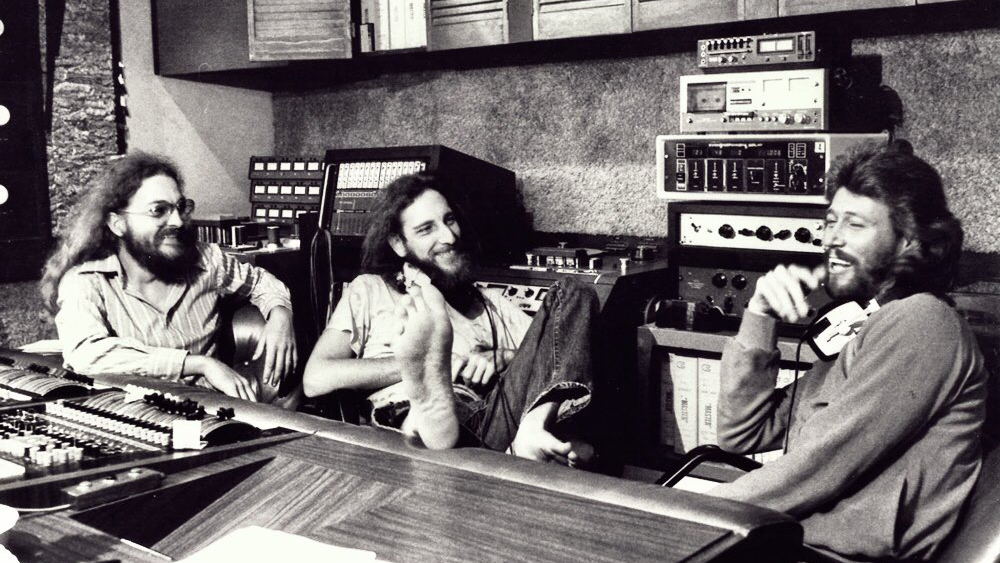

I’m intrigued by how the Gibb, Galuten, Richardson production trio worked. What was the division of labour there?

"Well, three is a magic number. ‘Cos when you have three people together and you respect each other, every time two people believe in something the third person goes 'I’m sure you’re right'. If you ever have a board where there’s four people, or a marriage where there’s two… when you disagree it’s very hard to resolve. But with three it’s much easier."

"Barry was the visionary. Because we had those common roots, when he would write a song I could intuit how he heard it, how he thought that it should go, what the rhythm should be like. He plays guitar, he knows his feel, his voice is a great instrument and he’s great with lyrics, so Barry would write the song, and I would be the music producer. I would hire the band, do the arrangements.

"Barry would be there over my shoulder, ‘yes, I think that’s right’ or ‘maybe it should be a little more of this’ – but for the most part we were musical compatriots and then Karl… he could make anything happen."

He could make anything happen?

"OK. When we were doing Streisand… Barry is a fan of voices hitting right on the note. He doesn’t like them sliding in very much and Barbara – as you know – is sliding into notes all the time. It’s a stylistic choice that Barry didn’t feel was perfectly matched to a rhythmic record like Guilty."

We created a thing called Solly, a solenoid-operated drummer. We had physical drums set in a room with arms to hit them and solenoids to move them

"Back then we were using these MCI tape recorders and Karl was intimately familiar with the punch-in circuitry. We were good at punching in and out. If I wanted something different for a bass part and one of the notes felt a little rushed I would say 'play it again' and could punch in and punch out on the individual note.

"I’ve done that 1000 times. But doing that within a vocal note would create a click, of course. So Karl redesigned the record circuit so that there was a gentle cross-fade. Now we were able to take the beginning of a note and pitch shift Barbara slightly and punch it back in so that we could make it spot on, the way Barry liked it."

"Karl made that possible. He also, with the help of a guy called Seth Snyder, created a thing called Solly that played drums on tracks later – a solenoid-operated drummer. We had physical drums set in a room with arms to hit them and solenoids to move them. Then we had a sequencer that could then play the drums."

What were the other innovations back then? What really created that sound?

"Saturday Night Fever was the first record that we did on multi-track tape. Phil Ramone, when he did A Star is Born, used this thing called MagLink. He could synchronise the film with the audio and Karl realised that we could use this thing to sync two tape recorders. "

"So we got a MagLink and the master tape would have SMPTE striped on it and the slave would have SMPTE striped on it. That was how we were able to have 18 tracks of Barry’s vocals, all on a separate machine. Sync it up and mix it down."

"Then we didn’t have to ruminate so much over doing comps. When I did the guitar solo on You Should Be Dancing there were 13 different guitar tracks. We had multiple people hitting buttons and moving faders in real time to do a comp. Before computers a mix would be like a performance! Blue [Weaver] and Dennis and other members of the band would help out moving faders."

And those famous multi-layered harmonies…

"Barry has the best metre of any vocalist that I’ve ever heard. When we did Too Much Heaven he overdubbed 18 tracks of vocals – three part harmony in two octaves, tripling each one, so that’s nine lower parts and nine upper parts.

"He did them all without listening to the others. He did 18 passes, one after the other, without listening because he would say 'by the time I’ve heard it it’s too late'. He knew exactly what he wanted to do and every vocal was not only in tune but they were exactly in time. Every breath was the same, every vibrato was the same. It was one voice 18 times."

How about other studio gear? What kind of other gear were you using for that sound?

"We always loved UREIs, [Universal Audio] 1176s, Fairchilds... as time went on I started working at Ocean Way and Allen Sides had the most unbelievable gear. So the further you go down the chain the less important the gear is. So the song is more important than the singer, the singer is more important than the microphone, the microphone is more important than the tape recorder.

"But the microphone is very important, so one of the things I loved about Ocean Way was if you wanted a Neumann 47 or a 67 Allen wouldn’t just have six to choose from, he would have six that were the best of the 30 that he’d owned throughout his career.

"So if you were recording Aretha you’d have three Neumann M49s and she would sing something on each of them and then you would pick the one that was most resonant with her voice.

When we did Too Much Heaven Barry Gibb overdubbed 18 tracks of vocals all without listening to the others. He did 18 passes, one after the other, all exactly in time

"The other thing we used to do was fine-tuning guitar amps. We used Vox AC30s a lot – the amps that Queen used. But everytime we would go into the studio you’d have to refurbish the amps because they would get tired – the tubes would begin to sag a little bit. But a guy named Mark Samson had this rig where he had keyed up a dozen AX7 tubes so they would be already warmed up. He would change out the AX7 tube while he was playing to hear which AX7 tube sounded better with which particular amp and which particular cabinet.

"And the piano was tuned every day. We never used the piano in France because it wouldn't stay in tune because they had no air conditioning and it was in front of a window that didn't close all the way… but technology always marches on."

What kinds of key keyboards were being used for things like Saturday Night Fever?

"Typically Blue played the Fender Rhodes. Fender Rhodes was a standard thing. Like on How Deep Is Your Love. When I met the Bee Gees when I used to use the ARP 2600 because it was flexible enough so that you could imitate a lot of instruments and people would hire me when they didn't want to hire an orchestra. I would do multiple tracks and bounce them together.

"Blue liked the Minimoog so he used the Minimoog a lot. And we had an ARP String Ensemble. But Saturday Night Fever was not a lot of syntheziser. We had real strings, real horns, we could afford a real budget."

And you would arrange and conduct the horns and strings?

"Barry and I would sit in front of the cassette machine and we would sing ideas to each other back and forth onto another cassette. And then I would convert those ideas into a real chart. And then I’d go out, usually to New York or LA, to do strings. Unless you're in New York, or LA, even in Nashville, string sections, were not very good."

"On Stayin’ Alive the string players were very good, but they were not tuned to the kind of rhythmic experience that we had. So because we had a drum loop, we would play them the drum loop and they would practice a little section until they had it perfectly in time. And then we would do the take and do that little section. And then we would do the next little section."

That high string sound, with the bass and drums really defined that disco sound. And it was copied so many times.

"It was a great time. Barry was very very musical and actually, the slide [sings a descending string slide] was Robin's idea. But I had studied orchestration and had sort of cut my teeth on Bartok and Stravinsky so I always liked the extra little tricky things."

The Saturday Night Fever soundtrack album was number one for 24 weeks from January to July, which is just amazing. But it kind of sealed its own fate by being so big. The balance kind of tipped and that whole sound went out of fashion really quickly. Did you feel that happening? Did you know you were on the crest of a wave?

"Oh yeah, for sure. But we never thought of ourselves as a disco band. I guess we thought we were immune to it. Because when you are young, and everything you do goes to number one, you sit around, not just wondering 'Is this going to be a hit?' but we would be 'How many weeks will this be number one?' It's easy to believe that the party will never end. But of course, if you have common sense, you realise that every party ends."

How did you feel about the ‘disco sucks’ movement and that backlash?

"I was detached from it. We didn't go out to discos, so it was not our milieu. But hindsight is 20-20. It should have been obvious, but when you're at the top and your fans are fans who love something, do you turn your back on them and say ‘I'm going to do it differently’?

When you're at the top and your fans are fans who love something, do you turn your back on them and say ‘I'm going to do it differently’?

"I think that it was probably harder on Robin and Morris than on Barry, and harder on Barry than on me and Karl. Barry was working with other artists and the Bee Gees were having a difficult time anyhow. They did that awful Sergeant Pepper movie. We did not produce the music and the music was pretty dreadful. There are a couple of great songs from that movie, but they’re not by the Bee Gees.

"And with the disco backlash the follow up album [Spirits Having Flown] was not really very big. And their albums following that were not good. We did a great record called He's A Liar but radio refused to play it because they thought that it was the Bee Gees personal affront to Robert Stigwood. Of course it had nothing to do with that, but they didn't want to play it.

"But Barry had a second act. He went from doing Bee Gees to doing Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton and Barbra Streisand and Diana Ross and Dionne Warwick. Karl and Barry and I were living in the control room 12 hours a day with everybody else coming in and out."

What was Barry’s relationship like with the other brothers at this time? What was the dynamic there?

"During Bee Gees records it was very much The Barry Show. Barry was the oldest brother. When you're two years older – when you're seven and five – there's a big difference. I think there was a period of time when Robin was extremely creative. Certainly half of the songs on Bee Gees’ first album are Robin songs, but Barry was always the leader by being the oldest.

"During the time when I worked with them Barry was clearly the creative force. Robin was a very talented singer and had really good ideas. Morris was always the glue that held them together. But Barry was the driving force."

And there's three of them, as you were saying before. So I guess Barry always had the casting vote.

"Well, yeah, but if Robin and Morris said 'No, I think we should do this' Barry would say 'OK' because there are three of them. You can't really can't go against them like that. They’re your brothers. You have to get along.

Those productions that you did with Barry and Karl. Did you have a favourite studio that you liked to go to? Or were you moving around?

"When we recorded Grease [written by Gibb, produced by Gibb, Galuten and Richardson] we recorded it in LA, I think it was at Heiders. And it was just a one day thing. We literally did the whole record in one day. Peter Frampton played guitar on it, Andy [Gibb]’s band played it. And I always loved Ocean Way. And in Miami, we worked at Criteria for years.

That’s how Joe Walsh and Don Felder got to play on Andy Gibb records, because they were in the next studio. And that's how I got to play on Hotel California

"Then Barry built Middle Ear so we had a studio in Miami Beach. I think that was a mistake. There was magic at Criteria, the fact that The Eagles were in the next studio when you were recording… people would run into other people and talk to them. That’s how Joe Walsh and Don Felder got to play on Andy Gibb records, because they were in the next studio. And that’s how I got to play on Hotel California. There was this great melding and communication.

"But when you have your own studio? That plus having to do the instruments one at a time. Not working in a great room with musicians playing live at once was what I think ultimately led to the end. But we did work. Barbara came to Middle Ear and sang. We had people come there and record and we went to LA and we went to New York.

"It's easy when you're making technological advancements to forget about the value of the emotional component. I think being around other musicians and being there with bands coming in and saying hello. These are moments you don't get when you're in your own garage."

How do you feel about the flexibility of the modern digital audio workstation? Do you wish that you had had that back then? Or or do you feel like the way that you did it was the right and proper way to make music?

"I don't think there's any right or proper way to make music. But I do think that in the beginning of the 21st century, as we were starting to use DAWs and starting to be able to use loops and copy and paste, the music suffered.

"I used to say that when I hear a new song, when I hear it the second time, I don't hear anything I didn't hear the first time. But when I hear an Ella Fitzgerald record from the 40s, I hear things on the 10th time that I didn't hear the first nine.

"But now with the tools and randomization and all sorts of other stuff going on, you can make things that are incredibly intricate. The way you can move with all those tools and effects in Ableton [Live]. It's like modern art. They didn't like impressionists. They were like 'This is not capturing this! This is not what it looked like!' And of course, the impressionist is going 'Have you heard of photography? You can already make stuff that looks like it looks like!' Capturing things in reality is incredibly valuable, but creative humans make stuff out of new tools all the time."

So you feel like musicians shouldn't worry about future tech? There's gonna be there's gonna be a balance somewhere?

"I'll tell you what. Some musicians should worry about it. So certainly people whose job it is to write a jingle, for a low-budget commercial, they're going to be out of work. Game music, too, all the low end music creation for games, commercials and films.

"There's a company I’m on the board of called Songistry. They can look at your deep catalogue of thousands and thousands of songs and when a music supervisor says “I need a song that sounds like the bridge of Start Me Up you can put that into the AI and it’ll come up with 15 songs that you've never heard of that have the same feeling as that. And you can licence them for peanuts, compared to when Microsoft paid $5 million to licence Start Me Up for the launch of Windows."

Do you see AI putting musicians out of work?

"Drum machines didn't put Steve Gadd or Jeff Porcaro out of work, but they put a lot of people out of work. So a lot of the yeoman's work will go away. Remember that AI is only trained on the past. Looking forward, there will always be the top, the cream, the 10th of 1%, the 100th of 1%… I don't know what realm Beyonce is in. But they're the very, very top. Those creators will always be there. It’s the middle class that won't be getting jobs.

The great stuff, the top 1%, will not be troubled by AI, it’ll just be a tool

"Like I would sit with Barry Gibb and he would sometimes thumb through books looking for interesting lyrics that would trigger an idea and a song. The great stuff, the top 1%, will not be troubled by AI, it’ll just be a tool. So if you need a second verse and you need something about going to the beach and so you ask AI, it’s one step beyond using a thesaurus. Is that cheating? They used to say it was cheating when you overdubbed. Cheating is a fuzzy line; it just goes on continuously."

What are you working on right now?

"The world has moved to the cloud. Young people don’t back things up, they don’t keep things locally and they assume everything lives in the cloud. Soon that will include our drivers licence and our home deeds and marriage licences, so Intertrust, who I’ve known for years, have been protecting and managing rights and permissions throughout the world for a couple of decades. Last year they issued over 20 billion DRM [digital rights management] licences."

Isn’t DRM more about preventing you from doing something than enabling freedom?

"It’s DRM, but maybe we need to use a different word. Every major studio, Spotify, Google, Amazon, everyone is licensed to our technology. You don’t know that when you use Netflix you’re using technology that’s licenced from Intertrust. It’s just managing your digital rights – if you own something you have the rights to listen to it or view it. There should be no impediments.

"That’s why my favourite topic about AI is why it will not destroy the music industry. The music industry is about relating to people and being fans of artists who are doing something or saying something. There’s no question that the deck will be shuffled and a lot of occupations will have to migrate but we will always love connecting with humans through music."

"I think one unintended consequence might be that people grow to like humans, they want to see human beings play music. We might have a resurgence of bands playing in clubs around the world where you go out at night and you hear live music from real musicians. That would be fantastic."

"I said, “What’s that?” and they said, “It’s what Quincy Jones and Bruce Swedien use on all the Michael Jackson records": Steve Levine reminisces on 50 years in the industry and where it’s heading next

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too