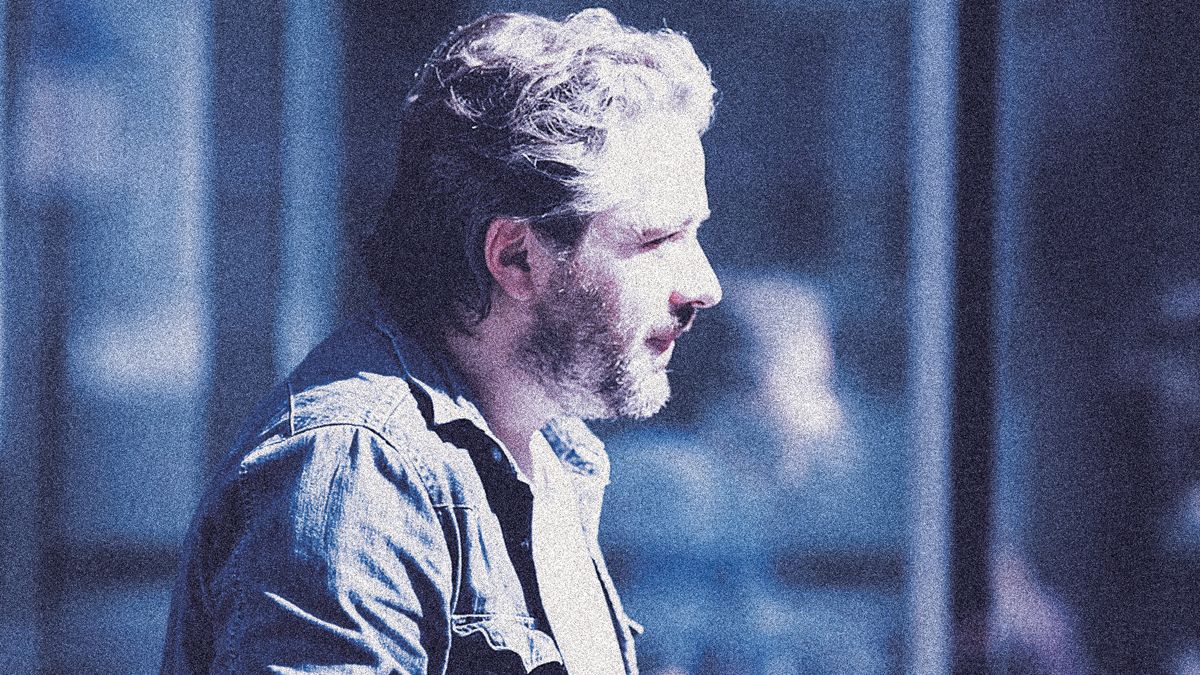

Alan Braxe: “Sitting in front of a computer and scrolling a bank of presets is not what I want to do with my life”

The French house legend on how switching to a simple hardware setup has inspired him to release music again

Sitting at the epicentre of the Parisian club scene in the mid-’90s, Alan Braxe shared his love of dance music with a diverse range of artists.

In 1997, his debut single Vertigo was released on Roulé, led by Daft Punk extraordinaire Thomas Bangalter. Joined by Benjamin Cohen, the trio created the three-piece dance group Stardust, releasing the global house hit Music Sounds Better With You the following year.

Stardust quickly disbanded, and Braxe founded Vulture Music as a vehicle for his own releases. A series of instantly recognisable hits followed, alongside remixes for the likes of Goldfrapp, Kylie Minogue and Justice.

In recent years, studio releases ground to a halt, though, as Braxe struggled for inspiration in a world of soft synths and plugins. Going back to basics with a Buchla modular system, he’s now ready to reinvent himself with his first EP in six years, The Ascent.

It’s been six years since your last release, so what have you been doing behind the scenes?

“I’d done some production and remixes for other artists and have been trying to work on music myself but it wasn’t really working. I’d been trying to record stuff for a couple of years but nothing was passing the demo stage, so I’ve been constantly working but was not satisfied by the result.”

You’ve never released a prolific amount of material under your own name. Is inspiration hard to come by?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I’ve been making music for 20 years and recently put my discography on paper and realised I’ve worked on quite a lot of tracks but most of them are remixes or collaborations. When it comes to releasing music as Alan Braxe I’ve only had a few releases so, yes, I want to be happy with it, not necessarily in terms of whether it’s going to please a lot of people or sell, but happy with the way I made it and how it sounds at a specific time.

“I recently changed my setup to make it much more comfortable. As a result, I feel much more relaxed and ready to release music without overthinking it.”

You were initially in Stardust who produced the classic single Music Sounds Better With You. Why was that project so short-lived?

“We did this song 20 years ago at a time when the whole French scene was very prolific and about making music for the 12-inch and club market with few other prospects. We spent one week in Thomas Bangalter’s studio, made the song and luckily it was a success. For us, it would have been enough to just release it as a 12-inch and have it played in clubs, but of course it went much further than that and we decided to leave it that way. In disco and dance history there’s lots of examples of bands like Stardust releasing one single and that’s it.”

For us, it would have been enough to just release Music Sounds Better With You as a 12-inch and have it played in clubs, but of course it went much further than that.

You’ve worked with a lot of the top electronic music producers in France. Was that a result of you all going to the same clubs in Paris?

“It started when I was 18, so quite a long time ago [laughs]. The scene in France was very small. It was all about going to clubs and house parties where I slowly met artists, musicians and DJs from the scene. The whole network was based on friendship, then and now, but at one point we were all fascinated by this new form of music and decided this would be our life. I met Thomas and Guy-Manuel from Daft Punk in a very natural way, at a very small party in Paris introduced by a common friend.”

Has that scene disappeared today?

“Today, it’s very different. I’m not going to clubs for fun anymore unless I’m DJing. Most of the time I’m living at home, taking care of my kids and working on music. I still love to meet people and collaborations could happen, but I see them more as my destiny rather than something that’s scheduled.”

You’re also re-launching Vulture Music. Is that just as a vehicle for your own material?

“I’ve decided to relaunch the label for my own music then maybe in a couple of years I’ll start to release music for other people again. Taking care of a label and releasing other artists’ music is very time-consuming, so I’m mainly focused on putting all of my energy into making, selling and promoting my own releases.”

Obviously, things have changed a lot since the label was last operational. Are you ready to embrace a new set of challenges?

“It’s going to be difficult. When I started 20 years ago the label was only selling 12-inch vinyl and that was the main income. There was no social media but our releases were selling really well. Now everything has changed, it’s all about digital communication, which is obviously a new world but also quite exciting.

“Releasing music has always been difficult and always will be. Sometimes people like what you do and sometimes they don’t; either way you have no choice and just have to deal with it.”

Your new EP The Ascent has a very ’70s feel…

“It makes sense that the music feels that way to you because most of the gear I used to make the EP with is ’70s-inspired. It’s been made in a most simple way with one instrument, one mixer, one compressor, one delay, one reverb and two EQs. It was a challenge for me to work with the most basic equipment possible and avoid using an excessive amount of gear, but that was my goal with this EP and for further music to come.”

What’s at the heart of your production process?

“I bought a modular synthesiser and my main idea was to use this as a sound source for everything, whether it’s drums, leads or pads. That was a reaction from working in the computer world, which is amazing but I began to find there was too much choice and decided to restrict myself in a very specific way, which I find exciting.”

Paralysis of choice is common with software. What advice would you give aspiring producers?

“I think limitation is the best way to go, but the problem with limitation in the computer is that it’s really hard to resist because there are so many great plugins, whether virtual instruments or emulations of hardware equipment.

“The marketing is also very strong. You’ll find a new compressor with a beautiful interface and although some of them sound really cool they’re not very expensive so you’re always tempted to try new instruments. In the end you have this big pile of plugins with hundreds of kick drums, snares or pads and that becomes too many elements to deal with, which can be really confusing.”

At what point did you decide that way of working was becoming unfulfilling?

“At some point I felt that sitting in front of a computer and scrolling a bank of presets is not what I want to do with my life. I found it quite counter-productive and, more importantly, it wasn’t fun.

“I’m not sure if the problem is restricted to hardware or software because it’s always hard to resist learning something new, but with the setup I’ve chosen, although doing that’s not impossible, I feel happy with what I have. I’m now as happy as a guitarist with his guitar or a pianist with his piano. There is a relationship between me and my instrument that’s pleasant but difficult to maintain with a computer.”

I’m now as happy as a guitarist with his guitar or a pianist with his piano.

Words on the new EP has some vocoded vocal snippets. Where were they sourced from?

“The vocals were selected by a friend of mine who is a French journalist. He sent me a list of words and I processed them in an iPhone app that synthesises vocals. I just entered the words and processed them using pitchshifting, delay and compression from my outboard gear. Forgive me for not knowing what it’s called, but it’s a very basic application for synthesised vocals from the App Store.”

The words seem to be communicating something conceptual...

“Not specifically. The goal was just to find some strong words that can act as a field of expression. I triggered a list of 40 or 50 words randomly on the sequencer and selected the bits that I felt had some sense of meaning, but it was not my intention to communicate anything beyond that.”

The key instrument in your new process is the Buchla modular synth, which we understand is a reboot of the 1973 Buchla Music Easel?

“That’s right. My computer completely crashed two years ago so I took the decision to use this as a starting point for something new. I decided to go with this Buchla modular LEM-208 plus a couple of very basic modules and focus on this and nothing else.

“I used the oscillators from the 208 and another oscillator as a sound source for most of the music I’m making, or sometimes the only sound source. It’s very refreshing and creative because suddenly you don’t think in terms of scrolling through a bank of sounds. It’s a new world where you’re just dealing with waveforms, oscillators and envelopes.”

How has this changed how you think about production?

“My whole way of thinking has shifted from one point of view to another, which, in my opinion, is more freeing because the modular is very versatile and you can potentially do anything from a kick or snare to a hi-hat or pure science fiction noise sound. Every day you have a new experience and there’s always something magical happening. As a musician, you’re put in a new situation where the automation you previously relied on disappears and you have to adapt to a new concept. No two days are ever the same.”

Did someone recommend the LEM-208?

“I came across modular synths three or four years ago through my cousin DJ Falcon who had a big Eurorack system set up. However, the Eurorack format sounded a bit dangerous to me because there are too many modules. It felt a bit like going back to the plugin world, whereas with the Buchla your choice of modules is quite limited.

“Buchla is a bit of a closed world. It’s not constantly evolving, so you have access to modules that were engineered 10-15 years ago but there are only 15-20 of them.”

Was your choice influenced by the original Buchla Easel?

“I went on the internet and found this guy called Todd Barton who does a lot of reviews and tutorials for Buchla. At first I just learned about Buchla without having the machine with me at the time and then I downloaded a user manual to try to understand how it all worked before deciding to go with the LEM-208.

“I like the way it sounds, but more important was the way it was engineered and the interaction you could have with it. It’s like being a kid with a toy; you’re just having fun. It’s simple yet complex and there’s a constant battle between these two factors depending on how deep you want to dig into programming the sounds.”

It comes in a briefcase but there’s a space to insert modules or a controller keyboard, so what did you decide to go for?

“I have four modules. One is dedicated to MIDI because some of the Buchla users are totally living in a Buchla world and don’t even have a keyboard, but I wanted to communicate with an external sequencer.

“There’s also a module that is mainly dedicated to random function called Source of Uncertainty, one oscillator and an envelope generator that can be used as an LFO.

“Because I’ve worked with synthesizers for a long time I knew all the terminology, but the difference is that you can have control of any parameter of any module yet it’s just cables. You patch your signal to several destinations, which makes it really fun and interactive, and when you feel something cool is coming you record. It’s versatile, fast and endless.”

Apart from sound sourcing, how is building a track different to how you previously worked?

“Well imagine that it’s 9:00am: you switch on the Buchla, which takes 10 minutes to get warm, and suddenly something interesting is starting to take shape. It’s very important to record as soon as something good happens because if you touch one knob by a millimetre you’ll lose your sound and never get it back. So I have a lot of takes lasting from ten seconds to two minutes, and start to combine and edit them before adding more Buchla on top.”

Once a track has taken shape are there instances where you know you need a particular sound and try to create it from scratch?

“It’s a good question because sometimes you start a track and reach a point where you need a pass sound or a snare drum. From there, I have two options, either I go back and try to program the sound I want or I use a Buchla sample that I’d previously saved to see if it works in this context.

“Another important element is the Akai MPC X, which is the centrepiece of my studio. It’s quite flexible because you can use it as an old-school sampler or a sequencer. Of course, you can’t edit the MPC X as far as you can with other DAWs, but you can copy, paste and crossfade and it contains a lot of the Buchla stock sounds I’ve created.”

From using the Buchla, how do you think the tonal characteristic of your music has changed?

“It’s not easy to answer. All I know is that the feeling of making music is back again. I’m no longer thinking about what I’m doing, I’m just doing it.

“I’m often surprised by what’s coming from the Buchla - it’s constantly offering you options and sounds that you didn’t have in mind so there’s a lot of happy accidents. When I started making music 20 years ago, I didn’t really know what I was doing. I didn’t have a big knowledge, I was just happy and excited and that’s how I feel now. I don’t know what I’m doing, but I like what I hear.”

When I started making music 20 years ago, I didn’t really know what I was doing, and that’s how I feel now. I don’t know what I’m doing, but I like what I hear.

The two tracks Repeater and Spacer have a beautifully rich tone to them. Blade Runner springs to mind…

“Repeater was not done on the Buchla, it was made on my former setup, but Spacer is 100% Buchla and I really love this track because it doesn’t sound like anything else. But you’re absolutely right, there’s a lead sound in this track and when I programmed it I had Blade Runner in mind.”

Is a lot less post-production required when using a modular synth?

“When it comes to processing I just have two very basic two-band EQs to add some high frequencies. What’s good about using the Buchla is that whether I’m working with a snare, pass or hi-hat it’s all coming from the same source. You can EQ or push some frequencies but it’s not like in the computer when you have one snare coming from one world, a kick drum from another and you have to EQ to match them. But what is important is reverb and delay, because when the Buchla sounds are dry they can be a little bit crazy, so you need something to sweeten them.”

How did you go about finding a suitable reverb?

“It’s a nightmare choosing reverbs because there’s a vast amount of them, but I wanted a very simple hardware reverb and love the Strymon BlueSky because it only has a few settings.

“The Strymon Magneto is also amazing. It was crucial on the track Spacer because it’s a pitchshifter and delay and can be used in multiple ways to create orchestration. Basically, I enter a melody from the Buchla and the Magneto adds three voices of harmonies with different delay settings to create a very complex sound bed.”

How are you mixing and mastering tracks within this new setup?

“The Buchla is going into my XLogic desk where there’s an insert on the channel going to an EQ and a compressor. When I’m happy I record through the X desk into the MPC X and patch that into six channels of the X desk which I then use as a tracking console and mixer. When a track is ready it goes through an old Universal Audio 2182 converter into a computer in my office where I record the mix through Digital Performer and send the file to a mastering studio.

“Basically, my knowledge in terms of how to master a track is very poor, and I don’t want to deal with that at all.”

How do you think your new streamlined setup will affect future productions and are you interested in taking the Buchla system out live?

“I’ll probably expand with one or two basic modules because I’m happy with what I have right now but will probably work towards producing music that’s a bit more club-friendly.

“For me, it’s hard to imagine using the Buchla live. Some artists are doing that with Eurorack but I honestly don’t know how they do it [laughs]. You have to constantly patch in real time, so it sounds too risky for me, but who knows: maybe at some point I’ll use a combination of real-time interaction with the Buchla plus some pre-recorded MPC sequences.”

Alan Braxe’s The Ascent is out now via Vulture Music. For more information on his work, visit his Facebook page.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

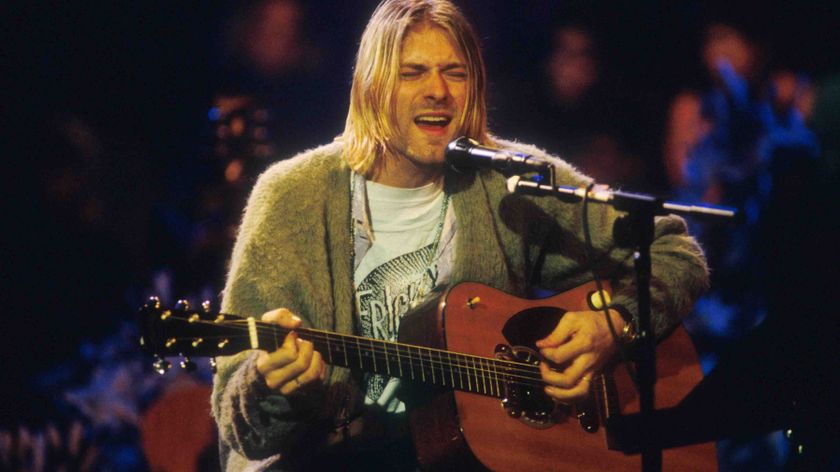

“We hadn’t rehearsed. We weren’t used to playing acoustic. Even the people from MTV thought it was horrible”: A new Nirvana’s Unplugged exhibition features not only Kurt Cobain’s $6 million Martin D-18E but his green cardigan too

“The screaming was deafening!”: How a Japanese tour transformed the career of a weird little band known as the ‘Beatles of hard rock’