"I wrote that riff when I was 15": How A-ha's Take On Me beat the odds against them to become one of the biggest songs of all time

The world may have discovered A-ha with Take On Me, but the Norwegian trio certainly didn't magically appear in the high reaches of the charts in 1985 as a fully formed band. There were crucial formative years as teenage songwriters, leaps of faith over the English Channel, and a fast track to developing a synth-led sound in London.

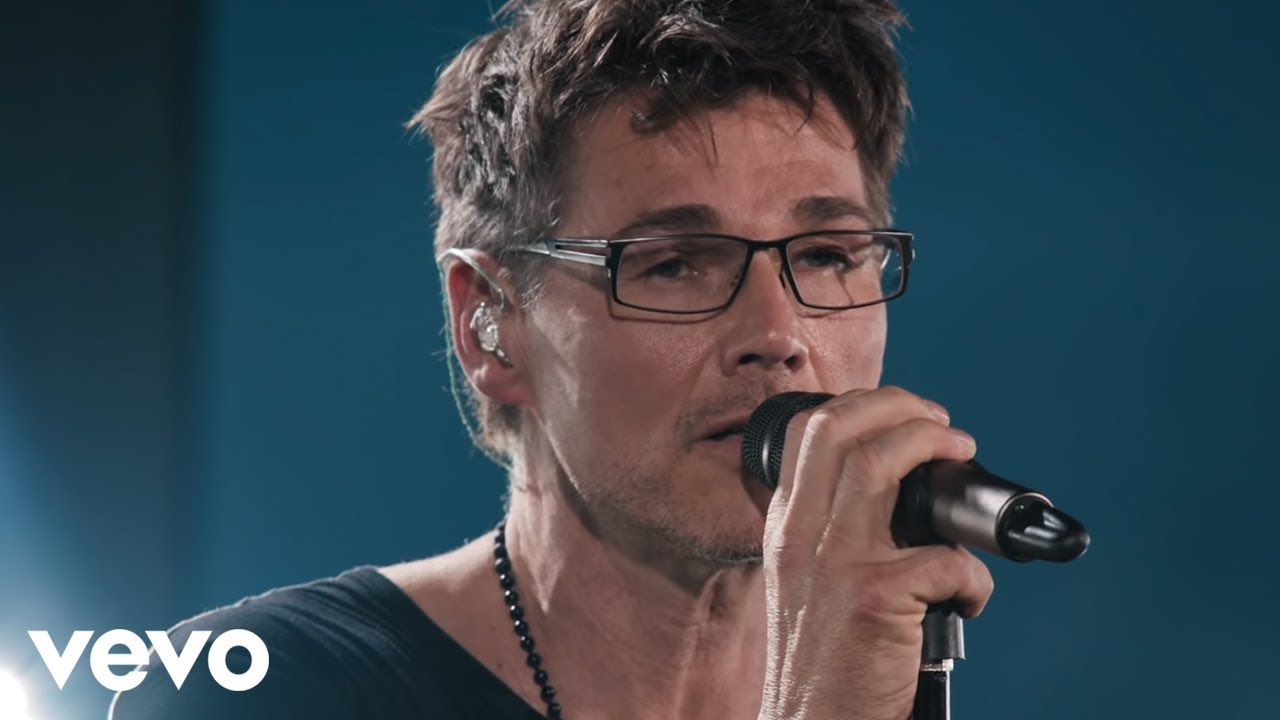

Nearly 40 years later it has songwriters Magne Furuholmen and Paul Waaktaar-Savoy reflecting with us in separate interviews from their respective homes in Norway and LA as A-ha's debut album Hunting High And Low is reissued as a sprawling six-LP boxset.

A post shared by a-ha (@officialaha)

A photo posted by on

It's a fascinating listen; charting ambitious young musicians who came to London with a dream of making it as pop-rock stars; living on their wits in bedsits by day and crafting their new sound recording demos by night in a South London studio as they developed a wealth of material; plenty of which never made the cut on the record. Even some of the demos of their biggest hits – including Take On Me – are vastly different from the radio mainstays we know today.

A-ha's classic synth-pop debut is a story that could have easily gone a very different way if it wasn't for the musicians involved, their determination to make it, and some fortuitous connections…

Before the three of you came to London as a band from Norway, you and Paul came over for a while on your own without Morten. Looking back, that idea of coming to England to make it as musicians seems like a huge leap of faith. Had the idea been on your minds for a while?

Magne: "Yes, for a long time. Paul and I had been together in bands since I was 12 or 13. And we just felt that there was no kind of chance to make it internationally coming from Norway because at the time it was sort of a wasteland in terms of pop culture. So there was a very clear kind of conviction that London was where we wanted to be. It was where all our heroes were from or had made it and we had a pretty strong conviction that this is where we need to be.

"That's the good thing about being young and with a common purpose in a band, rather than being a solo artist, you sort of prop each other up as you go. Even though things go from bad to worse in terms of living standards and having to do jobs to just survive in an interim period, we always had that belief that whatever we had going musically was somehow worthwhile to pursue. And London was where we wanted to be and where we thought we needed to be."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Paul: "From a fairly early age, we sort of made plans and I have to say we made a lot of different plans, and that is the one that worked. But from when we started high school that was sort of the game plan, and we got more and more determined as we went along. We had another band going at that time called Bridges and even then there was no in-between; you had to follow the plan.

"So when we sort of lost that band, Magne and myself ended up going to London the first time around, and then Morten needed another year to sort of come around to the set-up we'd thought up. So once we got there, of course, it took a year or two before we actually got anything going."

What was the music scene like in London at that time?

Magne: "I don't think we had a good idea of how much exciting music was being made in the '80s with the whole kind of influx of synthesizers on the level that was going on at the time. It wasn't something that we were aware of before we left. We had a more sort of romantic idea of London in the '60s and the '70s, and it was kind of a culture shock, actually, to come over and listen to the radio having new artists and new singles and such a variety of musical styles happening in the charts on a weekly basis.

We played pretty much any instrument that was put in front of us until it sounded ok

"It was just an onslaught of really interesting and new stuff. So it was almost like being schooled. We were flummoxed by the sheer magnitude of popular culture in London at the time. I think, looking back, you can see how fertile musically that period was. And we just had this romantic idea where we were going to be international pop-rock stars and we needed to be in London.

"We came from a country where basically radio wasn't playing much pop music and so it was just a real culture shock, and we kind of updated our sound just by necessity because we didn't have a band or a standard band format. We played pretty much any instrument that was put in front of us until it sounded ok. And synthesizers made it possible to go into a rented demo studio and just fiddle around and create something with drum machines – the Linndrum.

"We were ok musicians, we could play a variety of instruments, but we didn't have a fixed lineup, we didn't have any live situation going on. We weren't allowed to work in London. This was prior to the EU obviously, and, you know, we sort of snuck in on tourist visas and just had a pretty naive and romantic idea of how fast things were going to move and how much we were going to improve by being there. But looking back, that's exactly what happened.

"We just got sucked into this period in time where so much great stuff was coming out and we're just, you know, fortunate to be compared to that."

I think we rediscovered our love for pop songs

Paul: "Compared to Norway, which was a desert at that point, and now it's booming with lots of new music, but back then it was nothing and [in London] we were overwhelmed in a way because we got to hear so much new music.

"Up to that point, we'd been very introspective musically in a way. It was a lot of longer songs and more involved type of stuff. So I think we rediscovered our love for pop songs and we wanted to do our own as well. So we got very inspired to come up with stuff that was more immediate and had a more immediate effect on the listener. We started by watching everything we could see on TV and we started heading out to different clubs – wherever was very cheap to get in we would go."

In the A-ha movie, it's clear that you guys were living in quite basic and difficult conditions on both trips you made to London.

Paul: "Yes, so we loved places like Camden Palace because if you dressed crazy enough you got in for free. That was actually the plan – they'd pick you out in the line and say, 'Ok you can go in'.

"And that place in itself was hugely inspiring. The sound coming off of walls and the harshness – we just loved it."

It seemed like everywhere you looked there was a new sort of invention coming up – you'd have the Fairlight and the synclavier

Synthesizers were at the forefront of a lot of pop music during that time, was that a contrast to your previous band Bridges, who seemed more rock-orientated?

Paul: "Well, actually on the last album with Bridges [second album Våkenatt was recorded in 1980 and finally released in 2018] we had already made a decision that everything needed to be synths. So we forced our bass player to buy a bass synth and our drummer to buy synth drums. We couldn't afford the latest thing so it was more like the '70s versions of synths where we had to spend half an hour getting the next sound before you could play.

"We came over with a kind of crappy cassette with some demos and we realised we had to do something better. So we booked the studio in Sydenham in South London and the only thing we knew was that it would have to have a drum machine and a synth so that's the only reason we picked it, and it had to be cheap.

"We'd spent our teenage years sort of playing in straight-up bands so we were very inspired because at that point there was so much come new, exciting product coming out. It seemed like everywhere you looked there was a new sort of invention coming up – you'd have the Fairlight and the Synclavier. There were a lot of things to be curious about."

Morten wasn't with you on that first trip to London and you went back to Norway for a while to regroup with him before returning. Did you work on material for the first album during that time?

Magne: "Well we got some material together but I think the only song… well it wasn't even a song, but bits of Take On Me were part of that first round of the demos we did. The few months that we spent back in Norway, in a cabin outside Oslo were, I guess to get to know each other and get to work with Morten and put his vocals on our songs and stuff.

One rejection after another just made us more resilient

"So we did record like four or five demos, but none of which [made the album] except for the verse and the riff to Take On Me – not even with the same lyrics and not with the same chorus. So there were bits and bobs here and there but it was a very fertile time. We came [back] to England, I think, with four or five demos and sort of started schlepping around knocking on doors and trying to get people to listen to it. And one rejection after another just made us more resilient.

"We knew time and money were running out fast and we just needed to find a studio with enough instruments in it so we could actually make something happen. We spent the last money we had on this ambitious plan of recording five songs in two days, or whatever we could afford. I think we only recorded like two songs. And then the studio manager [John Ratcliff] heard it and he said, 'Oh, that's kind of interesting. Where are you guys from? What are you doing? I'd like to give you some extra studio time, if you can come in at night.'

"We did that and recorded another song. And then eventually recorded a song called Dream Myself Alive, which he really liked. And he said, 'I can maybe get you guys a singles deal' or whatever. And it just kept growing from there; he just gave us more time and we recorded more songs he thought were even better than the previous ones. And it just sort of snowballed into getting in touch with contacts he had in the industry and becoming our manager. It rolled on from there.

"But it wasn't exactly luxury life – we were sleeping in a basement in southeast London without windows. Sleeping on polystyrene sheets. But we never really faltered or gave up because we had a great time in the studio. We spent every night awake in the studio and slept during the day – it was fantastic."

The real outpouring of creativity started in Rendezvous studio in Sydenham

Did you have any of your own gear that you brought from Norway or were you completely reliant on the studio that you were going into?

Magne: "Well the first time around when Paul and I left Norway, we had one big synthesizer – a big Korg synthesizer, and Paul had an acoustic guitar and that was about it. Then for the second trip, we sold off whatever gear we had to be able to go together. So we basically just had a couple of acoustic guitars that we fought over – all three of us. Then we ended up with a couple of little synths lying around, but nothing major.

"The real outpouring of creativity started in Rendezvous studio, Forest Hill in Sydenham when we recorded those demos and we were just like kids in a candy store. That was the moment where we started to seriously reshape our sound into a more synth-based programmed variety, just by necessity."

The Prophet 5 really suited the music, because there were so many sort of atmospheric sounds. You just put your fingers on it and you had lots of ideas coming at you

Paul

Do you remember when you first encountered the Prophet 5 synth?

Magne: "There was a Prophet 5 in that studio and that was a shell shock. That was a game changer."

Paul: "The Prophet 5 really suited the music, because there were so many sort of atmospheric sounds. You just put your fingers on it and you had lots of ideas coming at you. I think before the first album was done, we probably had songs for three albums demoed in that studio. So it was a big period for us inspiration-wise.

"I'm not a guy to read manuals and stuff like that but for some reason with the Linndrum I didn't have to read them – I could just do it intuitively. Starting on drums, as my first instrument, you kind of just program it like you would play it if you have the chops to do it.

Is that the period a lot of the demos on the boxset come from?

Paul: "Yes and you can kind of tell; the stuff is super simple, when we first that are trying to figure things out in the studio, and then it got more and more involved as we went along.

"We would use everything we could get our hands on. The studio was pretty busy so there was always a band finishing and we were allowed to use that studio when there was downtime, so normally that was about four o'clock in the morning. We would sit there trying to stay awake and then go in at that point. We'd knock off the song before the next band would come in at 10am or 11am.

"But they always left some gear so we would be sneaking in, using whatever they left. It was perfect because we basically hadn't spent that much time together with Morten. So that was a nice time to sort of figure out what he can do vocally and where we were as a band."

It wasn't like we were trying to be these expert musicians, it was more about just using whatever tool was available to write and create sounds

Magne, your journey as a musician is particularly interesting because you were a guitarist in Bridges with Paul, but you switched to keys. Do you think that gave you a different kind of approach to writing melodic hooks?

"Probably. I guess both Paul and I both had a journey from when Paul was playing drums and I was the singer and the guitar player. And then he moved to guitar. So for a while, there were two guitars in the band. And he started singing and then basically suggested that I should change to a keyboard when our then keyboard player, piano actually, quit.

"I wasn't really too keen on it, but did whatever it took and we were big Doors fans at the time. I was super into Ray Manzarek and sort of modeled my keyboard style on him with playing bass and synth on the left hand, and a dinky organ sound on the right hand.

"But it definitely did something to my creativity – it changed the way I wrote definitely. I grew up [with musicians] – my grandfather was a musician, my father was a musician until his early demise. So I knew my way around the keyboard from a very young age and it was kind of interchangeable.

"I mean, to be fair, both Paul and I have always swapped instruments whenever it was needed – like if someone was better fingerpicking on the guitar. We were both writing on whatever instrument was available from the get-go, and from a very young age. So it wasn't like we were trying to be these expert musicians, it was more about just using whatever tool was available to write and create sounds."

I wrote the Take On Me riff when I was 15. I had no idea at the time that it would be such a definitive statement

And the Take On Me keyboard part you wrote, that was around when you were playing in Bridges with Paul?

Magne: "Even before. I wrote that riff when I was 15. I had no idea at the time that it would be such a definitive statement [laughs]. I remember Paul trying to diss it and saying, 'Oh this sounds way too commercial, it sounds like an advertising jingle or something', because we were into the '60s and more flowery, psychedelic darker stuff at the time. And I was like, 'Yeah but it's kind of catchy though, isn't it?' And it was actually Morten that had heard us play live and when we roped him in he was like, 'This riff has got to go on our first record. It's a hit riff.' And I said, 'Yeah, that's what I thought.'

"So it sort of travelled through two or three different songs in the process but it was always something that had survival skills. So that's my message to young kids; you're never too young to write a hit! So get cracking."

There's no filler in Take On Me; if you listen to the multitrack, every little part is a hook, you can hum any of those things by itself

But it was also a song that almost never became a hit – with the way it changed over the years, does it feel like fate looking back?

Paul: "A lot of songs that you work on, they might start someplace and then they take some years to get finished. So I mean, it wasn't that unusual in a way but with Take On Me, because it was our first [single] you wanted it to do well.

"You can hear all the different versions. We started out with crazy lyrics and became more… ok it can be poppy but not that kind of crazy. So the first chorus that I had bugged me and was a throwaway thing. And so it took a while to come up with a chorus that took it to a different place. Because it was so poppy, it kind of gave me a headache. So I wanted a chorus that could also be emotional.

"I hate that once you say the word chorus, people start reaching for high notes straightaway. So I was sort of trying to get around that by hitting the lowest note Morten could sing and then bringing it slowly up from that. So that was the concept. And then also incorporating that middle eight which was more like discordant stuff going around to make sure that it didn't get too sugary.

"Then finding the beat; the whole thing was like a big puzzle. There's no filler on that track; if you listen to the multitrack, every little part is a hook, you can hum any of those things by itself. You can whistle it – it's a very hooky kind of track."

You initially recorded Take On Me with producer Tony Mansfield in 1984 and when that version was released it didn't become a hit despite being played on Radio One – was that a shock?

Paul: "I have to say that there were some company politics in the background here. It wasn't just that the song didn't make it. There were elements between Warner Brothers and [British arm of Warners] WEA. It wasn't like they were bending over backwards to make that succeed. And it got to a point where the Warner Brothers end said, 'Don't do anything more with this, we're gonna do it. Don't touch it.' It was before we had any knowledge of that stuff – we didn't know.

"Within the record company, everybody wants to be the hero. Everybody wants to be there for their project, not your project. Obviously, that [second version's] video made us famous overnight, which wasn't the norm before that. So for us, we didn't go and tour the first album. Suddenly you could reach the whole world by just promo for the whole thing. We went on a 15-month promo three or four times around the world.

"That was the first time you could do that; before he would have to do an album and then tour to build it up from there. And of course, now we think that would have been great because then we could have guided our career [more]. But at the same time we got very quickly up to the level of having the name of the band recognised everywhere."

At that point we had been given a record deal based on our demos, which were 100% us without anyone else involved

What are your memories of the first album sessions with Tony Mansfield?

Magne: "The whole Tony Mansfield experience was slightly surreal, because at that point we had been given a record deal based on our demos, which were 100% us without anyone else involved. It was Paul and me producing demos of the songs and everything from programming, and playing stuff to sound programmed. All the old Juno synths, they didn't have MIDI at the time, and just used arpeggiation to sound like it was programmed by being a bit tricky with your fingers.

"But then going into the studio with Tony Mansfield, well, to be fair with any producer from the outside, it was a scary thing. And Tony came off a hot streak with a number one in America and he was kind of a big shot. We were sort of both reverential, but at the same time super scared that we would lose a bit of our soul with this guy coming in with tonnes of synths and Synclaviers and these machines that we had very little experience with – Fairlights and the like.

"So it was both an incredible opportunity but at the same time we knew that we were in a kind of precarious situation with it being a first album and a band that was just signed – we mustn't f*** this up. We were similarly excited and open to being challenged by him, and about equal measures of panicking that we would lose a lot of the stuff that was precious to us.

"I remember running in and out of the studio and tag-teaming each other; 'Ok, now it's your turn to go in and find out what he's doing now because it's scaring the wits out of me. He's taking the song into a new direction.'

"I think Tony was kind of high on the success he'd had and more concerned with making a statement as a producer than really delving into the sort of Scandinavian noir stuff that we were really into. So we were fighting tooth and nail to keep some of that in there.

"When we finished the recording we were kind of exhausted, but not completely sure that we had cooked everything the way we wanted to do it. A case in point is when the first version of Take On Me was released. It got played on Radio One a couple of times, and then just sort of dropped off the radar. And we were convinced that the record company would drop us and everything was over before it began. But we managed to convince our label to let us have a go at re-recording Take On Me with a different producer. And that's when Alan Tarney was suggested, and we jumped at the chance. Alan actually went back to the demo version and listened to it. He thought it had more charm and more buoyancy the way we had done it. And that's the version that everybody knows."

You ran out of time recording the album with Terry Mansfield at Eel Pie Studios – was that a stressful time?

Paul: I think it was stressful for everybody… because we didn't feel it was our fault. It was just waiting for him to sort of figure out what to do with the Fairlight or whatever. But then they started talking about like, 'Oh they might drop you – they spent all this money and we only have seven songs.'

"For me, I had just met Lauren [Savoy], who is now my wife. I was a little bit in that world too. I think it sharpened our senses towards the end of the album, and I was worried that it was going to get too poppy, so I was very happy to come up with The Sun Always Shines as the very last song to make sure that it had something else as well. And we got to tweak Hunting High And Low and re-record Take On Me so it helped sharpen the senses towards the end of the album [with producer Alan Tarney].

"But I think in a way, our lucky break was a guy, one of the heads in Warner Brothers in America, he heard the tracks and he loved it. So it sort of gave us enough funds to finish it off."

Magne: "The production relationship with Alan was much more fluid, and we felt much more in tune with Alan's approach. We felt like we were on a roll and I think that kind of reinvigorated the project. Also for the label too."

With nearly all the material for Hunting High And Low written when you were in London, did you feel like you developed as a band quickly when you were in the UK?

Paul: "Yes, absolutely. And on this boxset, you can hear the first track we did at that demo studio with Dot The I. You can hear that and then just a few months later, we would do all the other demos and all sorts of stuff that were b-sides, like What's That You're Doing To Yourself In The Pouring Rain. That was recorded up at the demo studio. And if you just compare the production on those two tracks, we kind of picked up a lot of tricks just in a few months."

Is it true that you wrote the album's closing track, Here I Stand And Face The Rain, while on holiday in Tenerife?

Paul: "Yes that whole song is from there – not a cloud in sight! That was also one that I felt was very special for the album. It goes between 6/4 and 4/4 and just had a very cool vibe. It's one of my favourites on that album."

Were you writing a lot of the genesis of the songs on guitar and transferring the melodies to synth, and did that give you a different take on things?

Paul: Yes, I've always done it that way. It's always been just a piano or guitar and normally guitar because of the second you sit down with a synth and you get another sound, then another sound – you get caught up in that instrument. But there's something very neutral with an acoustic guitar – I can hear in my head what the arrangement would be and it wouldn't be confused with the sound that wasn't right from a synth I was playing.

"A lot of times that's how we would work because there were only eight tracks and you had to program the drums first because you needed to know where the fills and everything were going. Then you could picture it in your head before you started spending tracks on it to make sure you didn't run out of places to go."

What guitar gear did you have back then?

Paul: "I bought the very first guitar synth made by Roland – the GR-300. You could also use it as a normal guitar. You can use it as a bass too because you can tune it down. For example, in the track Hunting High And Low that's actually my guitar tuned down to bass register. It gave you a kind of octave sound because you can hear a little bit of the guitar with the low end of the synth.

"Andy Summers used one in the Police on Ghost In The Machine. I remember at a party once in Soho, Manhattan Andy Summers came by and he saw mine and said, 'Damn it – I wish I hadn't sold that!'"

What was your role as a musician on the album - was guitar just part of the equation for you?

Paul: "I play as much synth on the album as Magne does. It's not really a band where you play this and I play that, it's really more we play all instruments, whatever it is. So whatever is lying around, that's what we play."

It's interesting to hear you perform the songs live now and the guitar layers you are able to bring forward.

Paul: "Once you play bigger places it's hard to get the same vibe when you take away the drums and the guitar something so immediate and something a little trashy about it that is nice in a live setting. You can't control it the same way you can control synths. So I think it really helps us live at least to have that sort of thing that isn't so perfect in a way."

The demos on the boxset are really interesting, charting the journey of the album's songs but also dramatic changes. The demo for the title track is pretty much a different song – an upbeat song. What convinced you to change it so much?

Paul: "That was one of those things where you thought it was going to be like an uptempo kind of thing and we tried it. And it wasn't bad, but I remember lying in bed and hearing that verse with that type of chorus in a totally different setting. I was super tired and thought, 'Will I remember that in the morning? I'll probably remember that in the morning.' But then I was like, 'No, I better go out and record it.'

"I heard that whole verse melody in my head. And it was very hard to find the chords because there's this one really weird chord in there that kind of transfers from A minor to C minor in the middle of that verse. And I'm thinking, 'What the hell is that chord?' Trying every chord I knew. So that really changed the whole song, and instead of trying to be catchy, it was trying to hit you in a different place."

Magne: "As a band, or as an artist, when you make demos, there's always one moment in the demo that is hitting the spot for you. And you really want that to be part of whatever you do going forwards. But sometimes you have to kind of kill your darlings. And there's a lot of that.

"There's a lot of times we felt like the demos had something that was lost. But then something new came in, and I guess temperamentally I was probably the one that was the quickest to sort of respond to new things and add things that I thought were interesting on top of new things.

"But there's always that kind of fear that, ok we lost something here. We got something new, but we lost something in the process. But obviously, with Hunting High And Low that that change took it from a tricky, forgettable song into a classic. So that was a major, major turnaround."

We latched on to it genetically, being from a part of the world where melancholy is a revered state

For me, that's very much that dark Scandinavian element that you referred to earlier.

Magne: "Yeah, I mean we didn't define it as a Scandinavian, we found a lot of that in music that we listened to growing up, whether it be things like The Doors – not typically Scandinavian, but we latched on to it genetically, being from a part of the world where melancholy is a revered state.

"So it's just a kind of an instinctual thing, but I guess the runaway success of Take On Me was what put us in a situation of being on the front cover of Smash Hits and pop sensations, pop idols or whatever you want to call it. We were always kind of fearful that it would overshadow a lot of that sort of more complex and dark music that we were attuned to and had been making throughout our history, and still wanted to champion.

"I guess first albums can be tricky in the sense that it's kind of make or break for you as fledgling young artists to get it right. And it's not like we knew it was a classic record that would be forever in the canon of pop music when we were doing it. When we were doing it we were already looking as to what we were going to do next. We've got to get songs like Scoundrel Days in there next time – things that really show a different side of the band to what's been shown.

"So we were already kind of onto the next project by the moment the recording was finished. It took a few years but finally in the perception of A-ha changed over the years from the first outing."

The album highlights that as songwriters you often avoid pop and rock cliches with your chord progressions. Where do you think that comes from – is it your upbringing in Norway and the music you grew up with?

Paul: "Yes, I think there's a lot of different things. First of all, it's before YouTube and everything, so this I remember sort of trying to figure out the guitar and then every chord you came up with you were convinced you invented it yourself. We didn't have a sense of knowing exactly what you were doing. And it's a little bit of that – always sort of fumbling around trying to find interesting things.

It's always where you think it's about to go wrong, or something stretches it a little bit to the side, that's what I gravitate towards

"My parents were crazy into classical music so they would always take me to monthly concerts and opera. I remember Prokofiev and the big theme from Romeo & Juliet and stuff like that. It would really get to me. And Grieg the Norwegian guy had some amazing chords – something about a nice selection of chords just really, really gets to me. I'm always trying to search for that and it's always where you think it's about to go wrong, or something stretches it a little bit to the side, that's what I gravitate towards.

"I can sort of see that from the very earliest songs I wrote, it's always been the same, you know? On the last Waaktaar-Savoy album we did there was a song [Fall's Park] that I was written when I was 16 and it could have been written by me yesterday. It's something I've always had an attraction to."

Is it true that Train Of Thought originally had a guitar riff in it?

Paul: "Yes, that one was actually a little bluesy then Morton really wanted to sing sort of like Bowie, Berlin-era kind of thing – the low [range] thing. And so the first one we did, it was called something different, and we loved it.

"It was one of our favourites early songs and I remember when the chorus was in 6/4. When we came into the studio to record it with Tony Mansfield he sort of leaned over to me and said, 'There's something wrong with the chorus'. He couldn't find the 6/4 on the Fairlight so we made it 4/4 to make it easier to program!"

The Fairlight obviously opened up new possibilities as a synth and sampler but there were clearly limitations too.

Paul: "He was the only guy who knew how to use it and everything we'd done up to that point, we had been playing live – even if they were programmed it was really just doing a Linndrum and sending a cowbell into a trigger. So it was like a lo-fi version of getting into electronic sounds.

"With [Tony], most things had to go through the Fairlight. And we're embracing it because it was brand new and it was exciting – it was the first time we could sample stuff. And I would say we were sort of onboard for a good half and then the other half it was maybe missing other stuff that we had already going in the demo."

There are a lot of songs from that era that obviously didn't make the album and are represented on the album in demo form. Have you got any personal favourites from that time?

Magne: "There were a few songs that I thought would be included in the first record, like The Love Goodbye. It was one of the things where the producer was very adamant about which songs he liked, and wanted to work on, and we always figured we can get back to these things later – we can get back to those songs.

We never expected to be posters on bedroom walls

"Tony Mansfield didn't really react much to songs like Scoundrel Days and things that had a darker flavour; he wasn't so interested at the time. So, I guess from [1986 second album] Scoundrel Days onwards we sort of took the reins ourselves – much to the label's chagrin. You can imagine having runaway success with Take On Me, and they're expecting you to churn out copies of that song for as long as you can.

"But we weren't being strategic, we were just being reactive – we never expected to be posters on bedroom walls. What do we do now? We have so much music we want to get out to the world, we've got to show more of what we're doing.

"At that point, we already had enough success that we could sort of dictate what went on the record and what was being championed as singles. We were a lot more adamant about the direction that we went in from there."

Paul: "There's a song call Never Never that has a middle eight that turned out to be the chorus of The Sun Always Shines On TV. You can see how songs can sort of start somewhere and be chopped up and then we use a piece somewhere else. I always like to see with other bands how that works.

"Driftwood was kind of cool, and with Monday Mourning I remember we spent a long time on that tuning beer bottles to do a kind of flutey sound which was a first for us. Then The Love Goodbye, I remember we had some string players that were friends of ours and I remember they played so out of tune you had to chalk mark the violins – 'Put your finger right there!'. It was weird.

"There's also a Norwegian track [Sa Blaser Det Pa Jorden] that was one of the first songs we recorded and when we played it to the record company in England, and they felt like it was a totally different band – the words made it totally different [for them]."

Magne: "We started in a band, writing and challenging each other when I was 12 or 13, and Paul was 13 / 14. And that's all we lived for; to write, record, play and perform songs. So obviously, there was a lot of material in the back history of our partnership that wasn't forgotten but surfaced later. I think every album has had that; 'What about this, do you remember this? What about this song? What if we do this one this way?' Then that in itself would spawn new things happening."

There's quite a few themes and motifs and things that were revisited over the years for various albums

I hadn't realised that Scoundrel Days was a finished song at the time of making the first album.

Magne: "Well it was a different – it was a slightly different version of it to be fair, but with both that and Take On, the riffs had kind of survived being in three or four different songs over the years. Parts of Scoundrel Days were equally old and came from our early formative years – there's quite a few of those elements here and there where we would dip back into our past. There's And Alone Is Love [from 1988 third album Stay On These Roads].

"There's quite a few themes and motifs and things that were revisited over the years for various albums. They would be put into a new context and maybe be given, in some cases a new chorus, different lyrics or different melodic movements.

"That middle section from Stay On These Roads came out of being squashed together with another song called Hurry Home, and that's the way Paul and I worked in the beginning. I would have a part, he would write a part for that or he would have a part, and I would write the part for that. Sometimes those parts would be taken away from each other again and would spawn a new song.

There's a lot to be learned from that in songwriting. You guys seemed open in the creative process and not being precious about songs; doing what was best for the part.

We were certainly much more open and sympathetic in the way we were collaborating at the time

Magne: "It feels more like necessities, and maybe it has to do with… I mean, we were certainly much more open and sympathetic in the way we were collaborating at the time. Much more in the group together and exploring ways of crystallising ideas into something. Taking two pieces of coal and rubbing them together doesn't necessarily make a diamond but sometimes you have to try different things and you have to juxtapose.

"Some songs are very clearly juxtaposed – like Manhattan Skyline. That was two separate songs and we sort of welded them together. So I guess you can call it openness. I mean, we were more open people at the time."

When you toured playing Hunting High And Low in its entirety a few years ago you chose to perform the demo version of Dream Myself Alive. Was that versions something you were particularly fond of?

Magne: "I think it's harking back to what I talked about a little earlier; this is almost like a disease with some artists, this sort of feeling that you lost a little bit of the original sentiment from the demo. So Dream Myself Alive on the album, I've come to like it over the years, but at the time it was a radically different approach instigated by Tony Mansfield at the time.

"I mean, the song's pretty much the same, but the version is vastly different. There's always that sense that there's something great about the atmosphere in that demo – maybe it's a little sadder, or it's a little more desperate, or it's a little darker or whatever. So over the years we've been afforded the luxury of releasing these demos and it's very different for the audience. They hear what's on record, and that's the definitive version, but for an artist very often, you have two or three different versions that all have something that you think is precious. Or not always precious, but it may show the audience who is interested the paths songs can take after being exposed to different treatment."

I don't think any of us realised how impactful that first record was going to be

You can hear the influence of your debut on what synth music and hit songs by artists such as the Weeknd with Blinding Lights and Harry Styles with As It Was. You were at the forefront of a sound.

Paul: "You can definitely hear things in certain tracks; 'Ah, that sounds familiar'. And it's just the way it is."

Magne: "It's pretty crazy to sort of be continuously reminded that what you did 40 years ago has relevance for generations growing up. Our fans are fiercely loyal and whenever a song comes out that sounds anything like any of our songs they always kind of point out, 'Oh, you should sue these guys. You should be credited.' Come on guys, it's a huge honour and it's a huge privilege to be quoted, to be emulated, to be copied. I mean, that's as good as it gets in pop music.

"We were just making music at the time, and struggling and trying to get it right. I don't think any of us realised how impactful that first record was going to be. We believed in it, but we didn't know that it was going to be the one statement that 99% of the listening world would equate with A-ha at the time.

- The six-LP version of Hunting High And Low is available now via BMG

Rob is the Reviews Editor for GuitarWorld.com and MusicRadar guitars, so spends most of his waking hours (and beyond) thinking about and trying the latest gear while making sure our reviews team is giving you thorough and honest tests of it. He's worked for guitar mags and sites as a writer and editor for nearly 20 years but still winces at the thought of restringing anything with a Floyd Rose.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

![a-ha - Take On Me (Official Video) [Remastered in 4K] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/djV11Xbc914/maxresdefault.jpg)