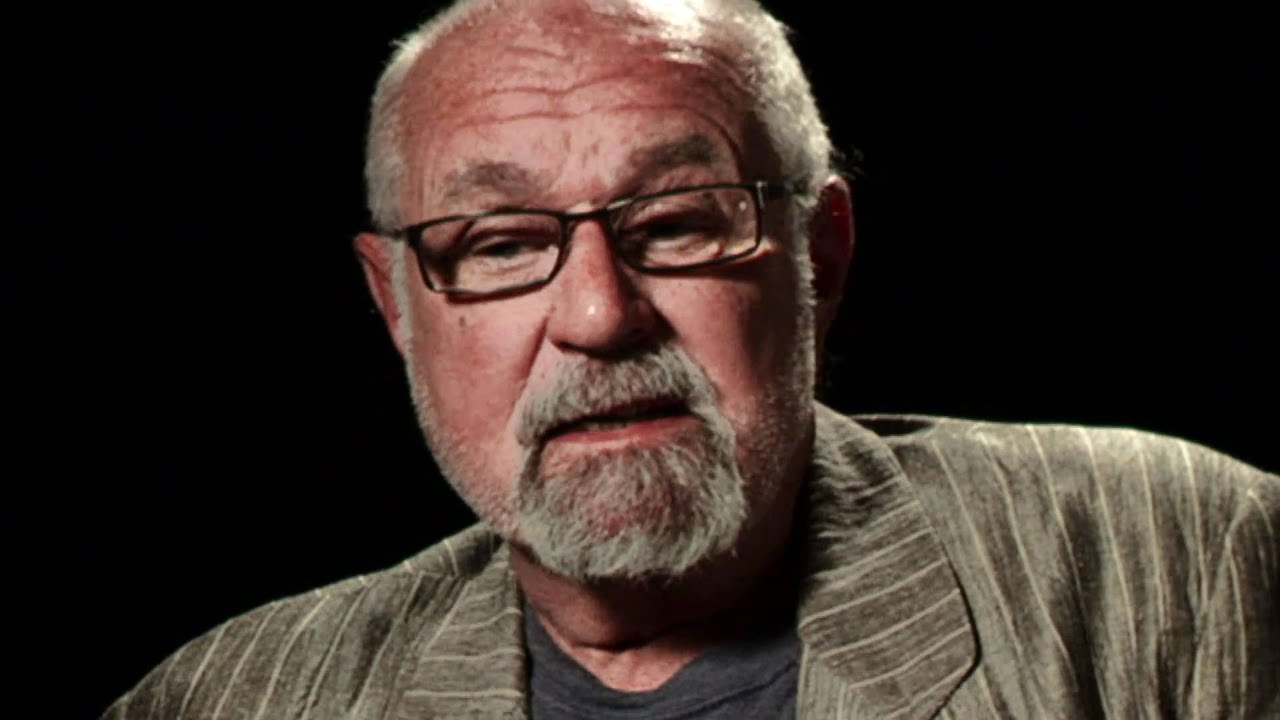

"It was ugly, like watching a divorce between four people. After a while, I had to get out": Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick on the recording of Abbey Road, track-by-track

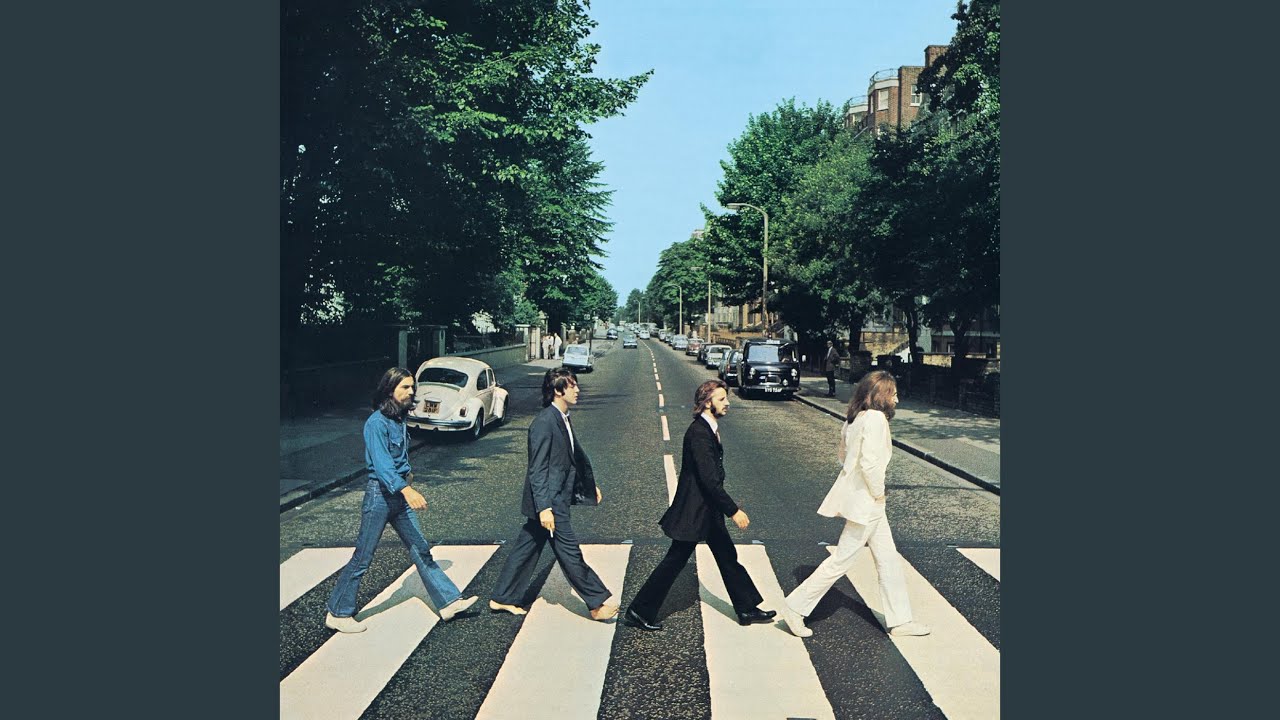

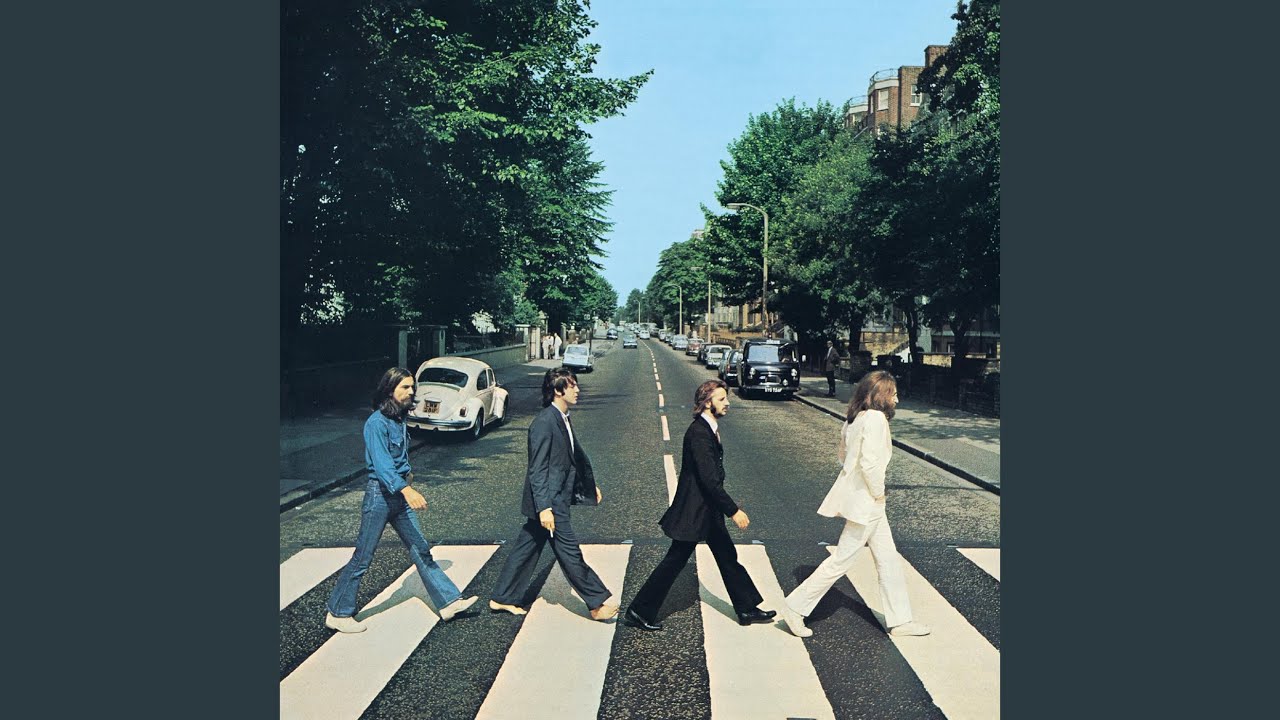

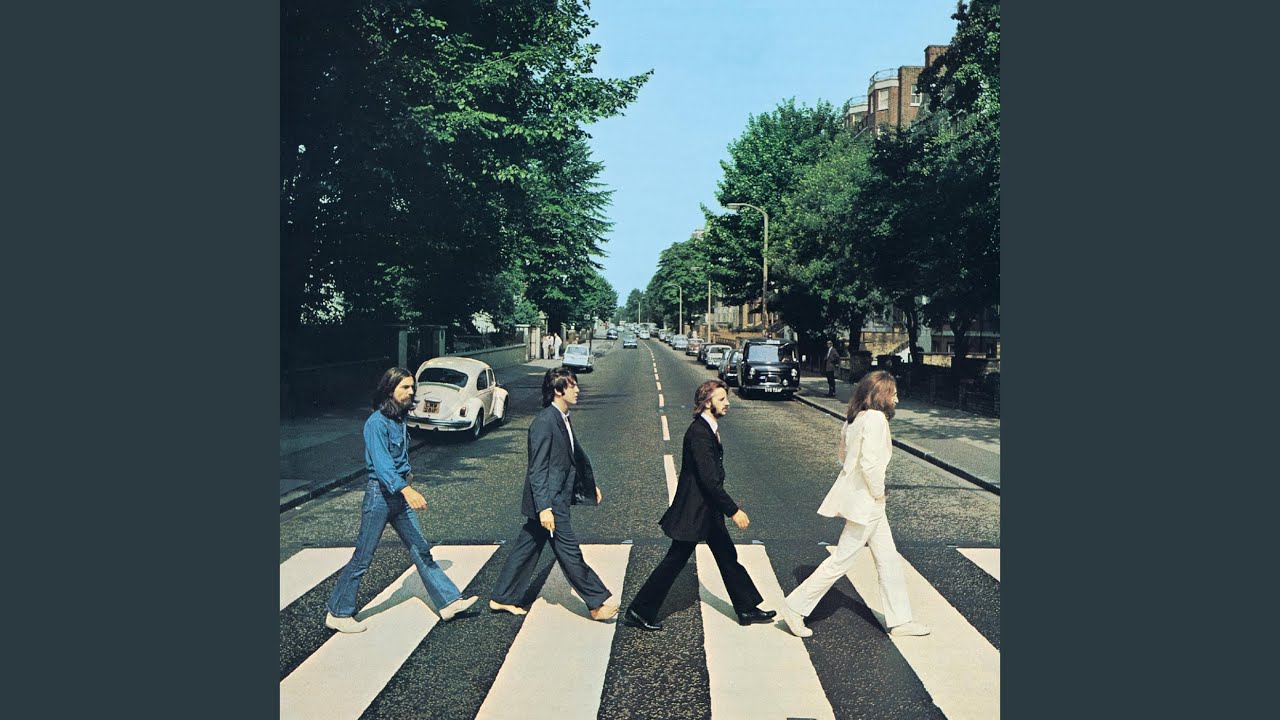

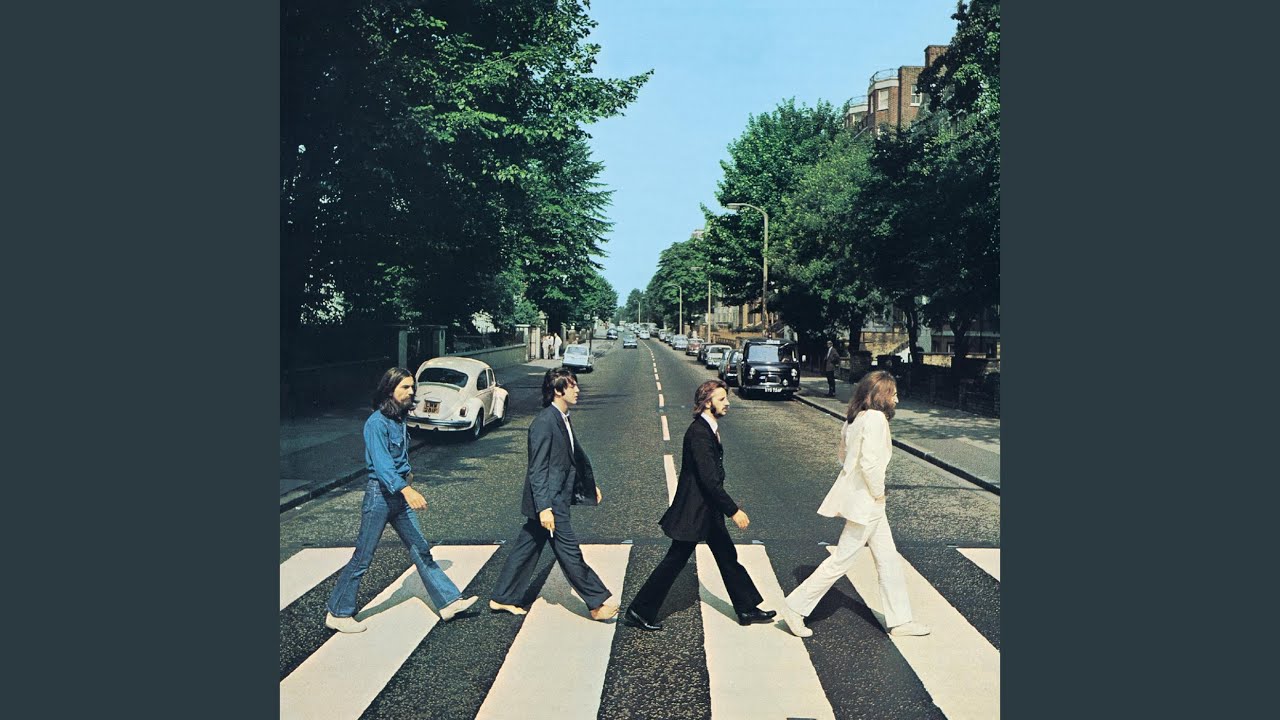

It's one of the most iconic album covers of all time: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr strolling across a zebra-striped street called Abbey Road in St John's Wood, north London.

It is an image as memorable as the moon landing - and one copied by tourists on a daily basis. (Even a few bands have paid homage, most notably Booker T & The MGs.)

Ironically, the shot was a last-minute decision.

During the recording of what was to be their swan song, The Beatles toyed with several titles, and Everest, a reference to the brand of cigarettes their late chief engineer, Geoff Emerick, smoked, was the favourite.

So Ringo said, 'Why don't we just shoot the cover outside and call it Abbey Road?'

"But the band decided they didn't want to trek to the top of Mount Everest to shoot the cover," Emerick told us, with a laugh whne we spoke to him in 2014. "So Ringo said, 'Why don't we just shoot the cover outside and call it Abbey Road?' Like many a Ringo suggestion, it won out."

During his tenure with The Beatles, Emerick had a few good ideas of his own - many of his sonic innovations, starting with the album Revolver, broke new ground and established techniques that are emulated to this day.

But Emerick almost sat out Abbey Road. Having begun his career at EMI Studios at the age of 15 in 1962 as a lowly tape copier and becoming, under the stewardship of George Martin, one of The Beatles' most-trusted sound architects, he quit working with the band during the recording of the double-LP The Beatles aka 'The White Album.'

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"The group was disintegrating before my eyes," says Emerick. "It was ugly, like watching a divorce between four people. After a while, I had to get out."

A year later, however, he was drawn back to work with Martin and The Beatles with the promise that the band would be on their best behaviour.

Emerick missed a few sessions for the album that would eventually rename EMI Studios, but in the end, he says, "I'm glad I came back for the final bow. To have missed being a part of the Abbey Road album, I'd still be kicking myself."

"[The White Album] was a nightmare. I was becoming physically sick just thinking of going to the studio each night

Geoff Emerick

Things must have been pretty awful during 'The White Album' for you to up and leave. Walking out on The Beatles - not many people would have done that.

"Oh, it was a nightmare. I was becoming physically sick just thinking of going to the studio each night. I used to love working with the band. By that point, I dreaded it. Getting out was the only thing I could do."

I was surprised and pleased at how everybody got along

Even so, you returned because the band promised to make nice and get along for Abbey Road.

"That's right. It came about through a conversation George Martin had with Paul. I had left EMI, but I was employed by The Beatles and was overseeing the construction of a new studio for them at Apple.

"After Let It Be, which I understand was not very pleasant for anybody, Paul was very keen to make a record the way the band used to. He wanted George Martin and I behind the console and everybody working together. He said things would be better than what they had been."

Did you take Paul at his word, that there would be a spirit of harmony?

"Yes, I did take him at his word. And John said the same thing to George Martin. In the back of my head I might have had some reservations, like, 'Well, we'll see…' But I was surprised and pleased at how everybody got along."

By that time, they'd been literally incarcerated at EMI. They grew to truly hate the place

Did you have any idea while you were cutting Abbey Road that it would be The Beatles' last album? Was anything said to that effect?

"I didn't think it would be the last one. And nothing was said to indicate that, at least not to me. As far as I understood it, we'd be working on another record in the new studio I was building at Apple. The band was getting along better. The mood wasn't bubbly and fun all the time, but it was a hell of a lot better than during the previous year.

"The only hint they gave me or anybody was on the album cover, where they're walking across the street. For people who don't know the geography, they're actually walking away from the EMI Studios - or Abbey Road, as everybody knows it now. This was intentional on their part - they didn't want to be seen as walking toward the studio. When I saw that photo, I did think to myself, 'They're sending a message.'

"By that time, they'd been literally incarcerated at EMI. They grew to truly hate the place. It certainly wasn't the most luxurious studio in the world. It was cold and quite uncomfortable, and EMI was always quite slow to embrace new technologies - we were the last to get four-track and eight-track recording decks. In fact, Abbey Road was the first album where I got to use an eight-track console."

This was the first time I was able to record Ringo's kit in stereo

I'm curious: The Beatles were the biggest band in the world - still are, really. Couldn't they have told EMI, "We want a better console, better accommodations"?

"No, it was against the rules at EMI. I remember at one point they wanted some covered lights in Studio Two, a bit of mood lighting, and the word they got back was 'We can't do that sort of thing.' So the band ended up setting up their own little area in Studio Two, with little lamps of their own and things to make it more homey."

Ringo's drumming is extraordinary on Abbey Road, his tom fills especially. But there's a different sound to his drums as well; they envelop the songs.

"I chalk that up partly to the technology. For the first time we were using a transistorized mixing console. Up to this point, all the albums had been recorded on a tube desk. But this luxurious transistorized desk had a limiter and compressor on every channel and selectable frequencies - it was quite a change.

"Regarding Ringo's drums, this was the first time I was able to record his kit in stereo because we were using eight-track instead of four-track. Because of this, I had more mic inputs, so I could mic from underneath the toms, place more mics around the kit - the sound of his drums were finally captured in full.

"I think when he heard this, he kind of perked up and played more forcefully on the toms, and with more creativity."

John absolutely hated Maxwell's Silver Hammer

Ringo was still draping tea towels over his drums, something he started around the time of Hey Jude and The White Album

"That's right. He did that on a couple of things. Come Together, Something…those are the ones that come to mind.

"You know, now that I recall, the transistor desk wasn't without its problems. It delivered a bit of a softer sound - the guitars, the bass, the snare and the bass drum were all a bit softer and warmer. It took a little bit of time for the guys to get used to it.

There wasn't the kind of out-and-out fighting and bickering that you witnessed in '68, but there was tension. Didn't Ringo walk out again, as he did during 'The White Album'?

"Yeah. that was because John wasn't happy with the drumming on Polythene Pam. He had some problems with Ringo's performance and Ringo got pissed off and split for a couple of days. But he came back and redid the track and John was pleased.

"That was the only bit of real tension - well, except for the fact that John absolutely hated Maxwell's Silver Hammer. My word, that song drove him totally mad, and he certainly made everyone aware of how much he hated it." [laughs]

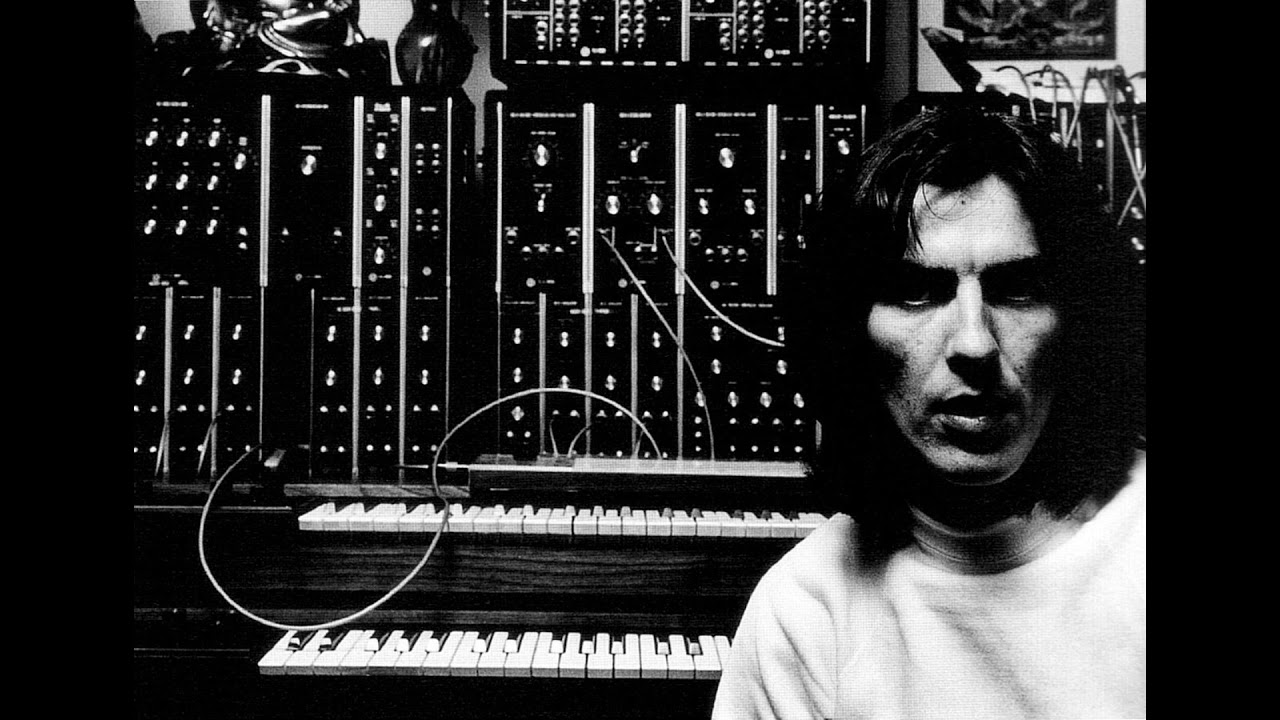

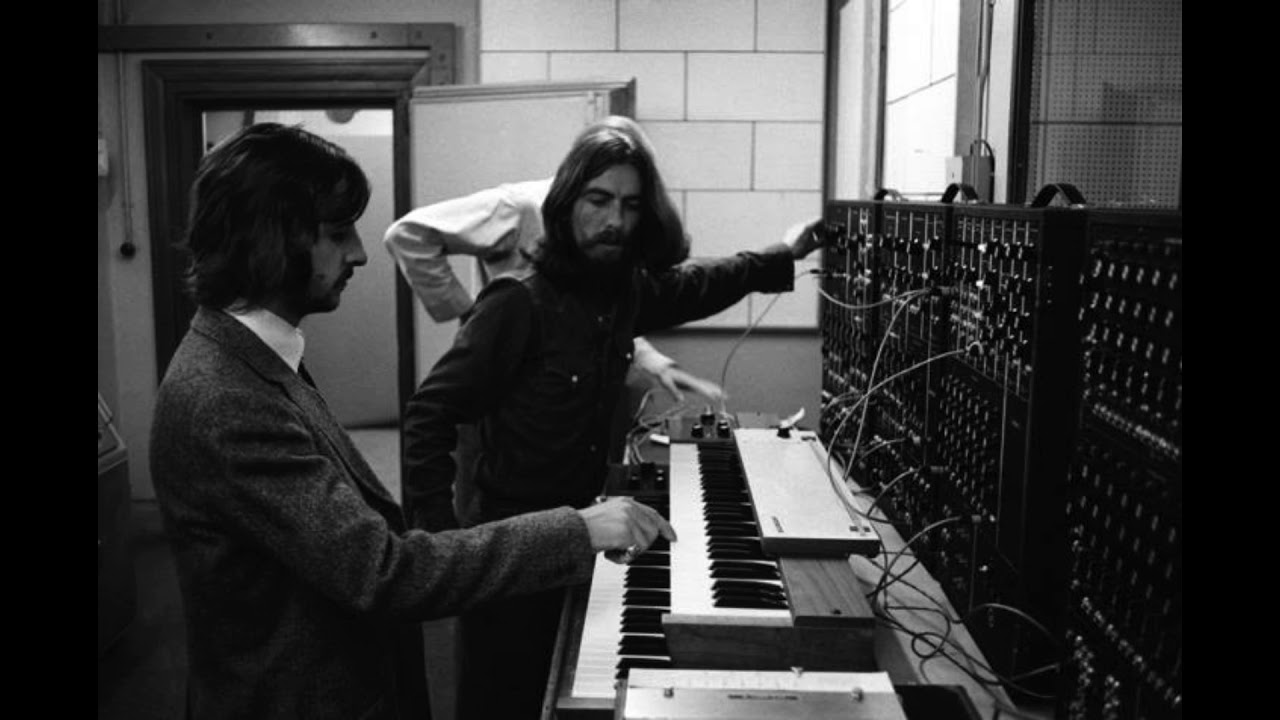

The Moog synthesizer was a new addition to The Beatles' lineup of instruments on Abbey Road. Do you recall any new guitars or drums coming in?

"No. I really couldn't pay attention to that side of things, although I was quite fascinated with what they were doing with the Moog. I was more concerned with tones and getting sounds right. Don't forget, before then, everything was being monitored in mono; this was the first album we recorded in stereo."

Abbey Road: Geoff Emerick's track-by-track

Come Together

Paul might have been miffed, but I think he was more upset about not singing on the choruses – John did his own backing vocals

"I remember John came in with a basic framework for the song, but at first he played it a lot faster. Paul suggested slowing it down and making it more 'swampy.' John quite liked that idea.

"Some weird things happened, though: Initially, Paul played the electric piano part, but John kind of looked over his shoulder and studied what he was playing. When it came time to record it, John played the electric piano instead of Paul. Paul might have been miffed, but I think he was more upset about not singing on the choruses – John did his own backing vocals.

"Ringo used the famous tea towels on his drums on Come Together, a terrific effect. Loud drums would have destroyed the song's spooky mood."

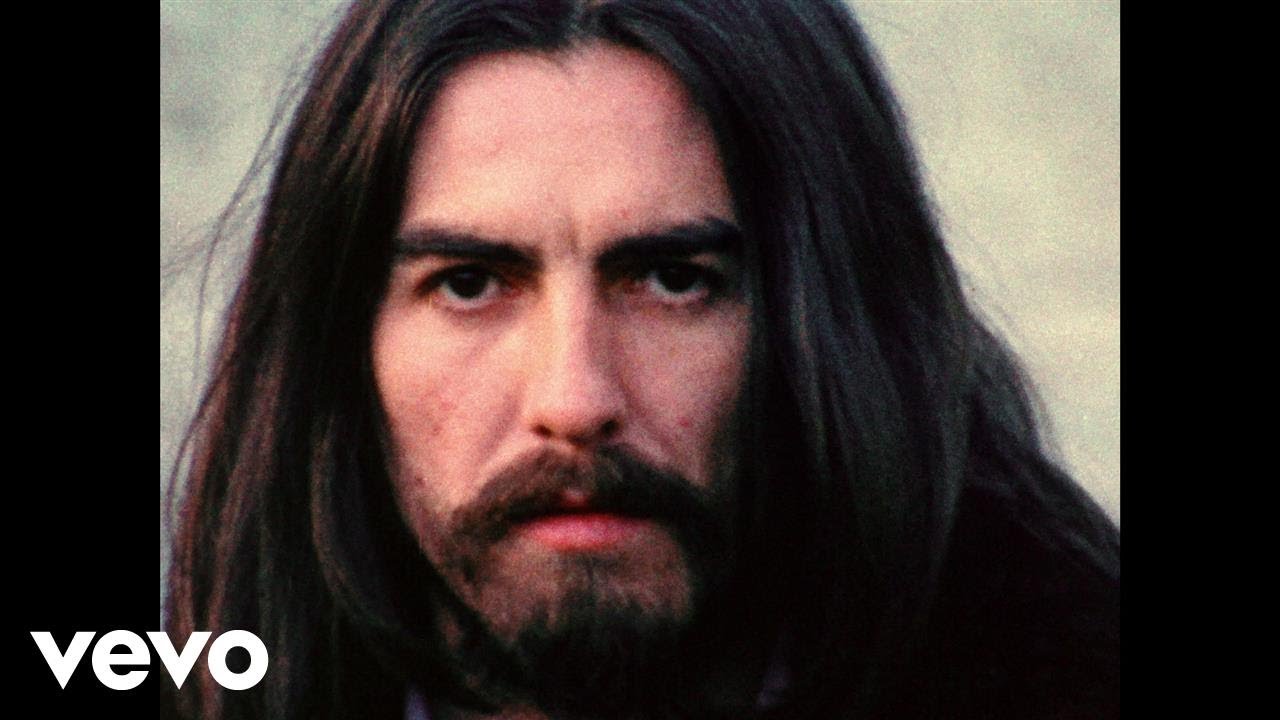

Something

"George had a smugness on his face when he came in with this one, and rightly so - he knew it was absolutely brilliant. And for the first time, John and Paul knew that George had risen to their level.

"Paul started playing a bass line that was a little elaborate, and George told him, 'No, I want it simple.' Paul complied. There wasn't any disagreement about it, but I did think that such a thing would never happened in years past. George telling Paul how to play the bass? Unthinkable! But this was George's baby, and everybody knew it was an instant classic."

"George really hit a personal best as a guitarist, as well. He played a guitar solo, but a few days later he decided be wanted to redo it. By that point we only had one track left and that was for orchestral overdubs. George cut a new solo live with the orchestra. It was a gamble, but he did it in one take, and it was beautiful."

Maxwell's Silver Hammer

John called it 'more of Paul's granny music'

"There were two struggles going on with this song: Paul and John fighting over whether it should even exist! [laughs] John called it 'more of Paul's granny music.' But there was my own struggle coming up with the sounds that should go on it.

"For the hammer bits, we actually had to rent a proper blacksmith's anvil. The thing weighed a ton, as did the hammer used to strike it. Ringo tried but he just couldn't hoist the hammer in a way that allowed him to hit the anvil with the correct timing, so Mal Evans [one of The Beatles' roadies], who was a large man, he wound up doing it.

"The other thing was the Moog synthesizer solos in the middle and end, which sound almost like a Theremin. The Moog was a fascinating new instrument for everybody - George, in particular, loved working with it – but Paul played these solos. He tinkered around until he got a really incredible, spacey sound that worked quite well."

Oh! Darling

"[EMI engineer] Phil MacDonald worked on this one.

"I remember hearing that Paul kept rehearsing the vocal lying on his back, and that he used to come to the studio quite early, before any of the other guys were supposed to be there, just so he could do it over and over again. He was searching for something, a Little Richard vibe perhaps.

"Artists are artists - you never know what drives them to do what they do, but you can't deny the end result, which is one of his most powerful vocals. He cut the final take standing up, I believe. It's something John could have probably knocked out in a couple of passes, but Paul had to work himself up for it."

Octopus's Garden

"George worked a bit on this song with Ringo, but I'm not sure how much he contributed. Ringo always felt shy about showing any of his songs to the other guys, but George was very keen on this number, so that helped. And it was a really good song – one of Ringo's best."

"There's this fun bit where you hear bubbles, as if you're underwater. Ringo tried blowing bubbles into a glass of water which we mic'd very close.

"In the end, I recorded his vocals, fed them into in a compressor and triggered them with this pulse-like tone that created a wobbly, 'bubbly' sort of sound."

I Want You (She's So Heavy)

"A fascinating song, very indicative of John's mood at the time - he was consumed with all things Yoko.

"It goes from hard rock to almost jazzy, bossa nova. Of course, there's the famous ride-out, the riff being repeated many times. George put some very intense Moog sounds down and Ringo played with a wind machine - the whole thing grew louder and louder till it got close to a breaking point.

"I thought the song was going to have a fade out, but suddenly John told me, 'Cut the tape.' I was apprehensive at first - we'd never done anything like that. 'Cut the tape?' But he was insistent, and he wound up being right. The track, and side one, ends in a very jarring way."

Here Comes The Sun

The Beatles: George Harrison Abbey Road lead and chord guitar lesson

"Another George winner, and again, he knew it - his confidence was growing each day.

"Ringo's tom fills really make the song, but funnily enough, he hated doing them because he could never remember what he was did one take to the next. I think that's why his fills are so spectacular - he felt that he would never reproduce them, so he'd better get 'em right.

"We added some orchestration to it, but nothing that overwhelmed. I think George was starting to like the idea of 'bigness' at that point, something he obviously carried over when he made All Things Must Pass with Phil Spector."

Because

It was an amazing recording, and probably the first bit of real camaraderie between the boys

"John said that this was based on Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata, on hearing Yoko play it and asking her to play it backwards. Personally, I can't hear the connection at all.

"It was an amazing recording, and probably the first bit of real camaraderie between the boys. I think they liked putting down their instruments and just singing together for a change. John, Paul and George sat in a semi-circle to do the harmonies and Ringo sat off to the side to lend moral support."

"We recorded the vocals multiple times until we finally had it right, but the funny thing was, each take was brilliant. They sang flawlessly. So what you have is nine-part harmony: three Beatles' voices times three. They made up their own choir."

The mini-suite: You Never Give Me Your Money, Sun King, Mean Mr Mustard, Polythene Pam, She Came In Through The Backroom Window, Golden Slumbers, Carry That Weight, The End

Each track could have stood on its own

"Sun King and Mean Mr Mustard were two separate songs, but we did record their backing tracks together.

"The same for Polythene Pam and She Came In Through The Bathroom Window - they were recorded together as well. Of course, the overdubs were done on different days and in different studios.

"Each track could have stood on its own, and I suppose Sun King does sound like it's a complete song in its own right. A concept started to come from Paul to tie the songs together, which helped to make the numbers seamless and unified.

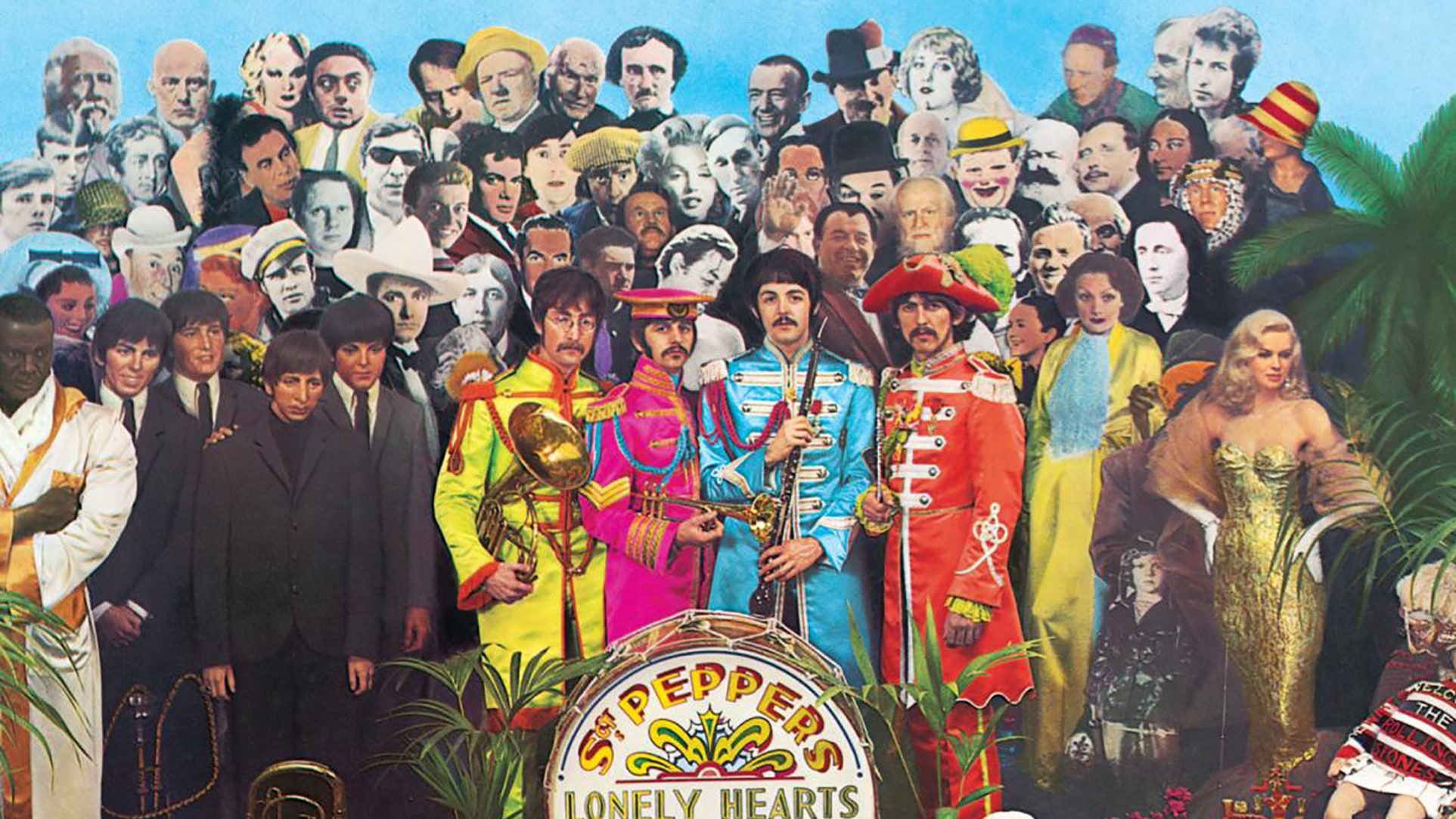

"The same thing held true for Golden Slumbers and Carry That Weight: everybody was firmly on board with unifying the songs - well, except for John, who had to be talked into it. He didn't want to do another 'concept album' like Sgt Pepper.

"And then, of course, we get to the famous parts of The End, the drum solo and the three-way guitar solos. The thing that always amused me was how much persuasion it took to get Ringo to play that solo. Usually, you have to try to talk drummers out of doing solos! [laughs] He didn't want to do it, but everybody said, 'No, no, it'll be fantastic!' So he gave in - and turned in a bloody marvelous performance!

"It took a while to get right, and I think Paul helped with some ideas, but it's fantastic. I always want to hear more - that's how good it is. It's so musical, it's not just a drummer going off.

"The idea for guitar solos was very spontaneous and everybody said, 'Yes! Definitely' - well, except for George, who was a little apprehensive at first. But he saw how excited John and Paul were so he went along with it. Truthfully, I think they rather liked the idea of playing together, not really trying to outdo one another per se, but engaging in some real musical bonding.

"Yoko was about to go into the studio with John - this was commonplace by now - and he actually told her, 'No, not now. Let me just do this. It'll just take a minute.' That surprised me a bit. Maybe he felt like he was returning to his roots with the boys - who knows?

"The order was Paul first, then George, then John, and they went back and forth. They ran down their ideas a few times and before you knew it, they were ready to go. Their amps were lined up together and we recorded their parts on one track."

"You could really see the joy in their faces as they played; it was like they were teenagers again. One take was all we needed. The musical telepathy between them was mind-boggling."

Her Majesty

"Putting that on the album was a complete error. Paul had done a little demo of that, and [assistant engineer] John Kurlander ended up splicing it onto the end of the album's reel by accident.

"It was never supposed to go on at all. But after the acetates were made, Paul heard it and liked it, so it stayed. Quite an odd way to end a record of this nature, but as always, the Beatles made strange things work."

John Lennon's 10 greatest songs with the Beatles and beyond

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“A fabulous trip through all eight songs by 24 wonderful artists and remixers... way beyond anything I could have hoped for”: Robert Smith announces new Cure remix album

“It pretty much half killed us. Whether the band would continue was in the balance”: The Radiohead album that almost broke up the band, turned the music industry on its head - and became their best record