A century of tone: the story of the Martin dreadnought

A pilgrimage to Nazareth to meet Martin's makers

On North Street in Nazareth stands a building that represents the spirit of Martin like no other. It’s the factory that founder Christian Friedrich Martin built in 1839 and it is where the company’s modern history really began.

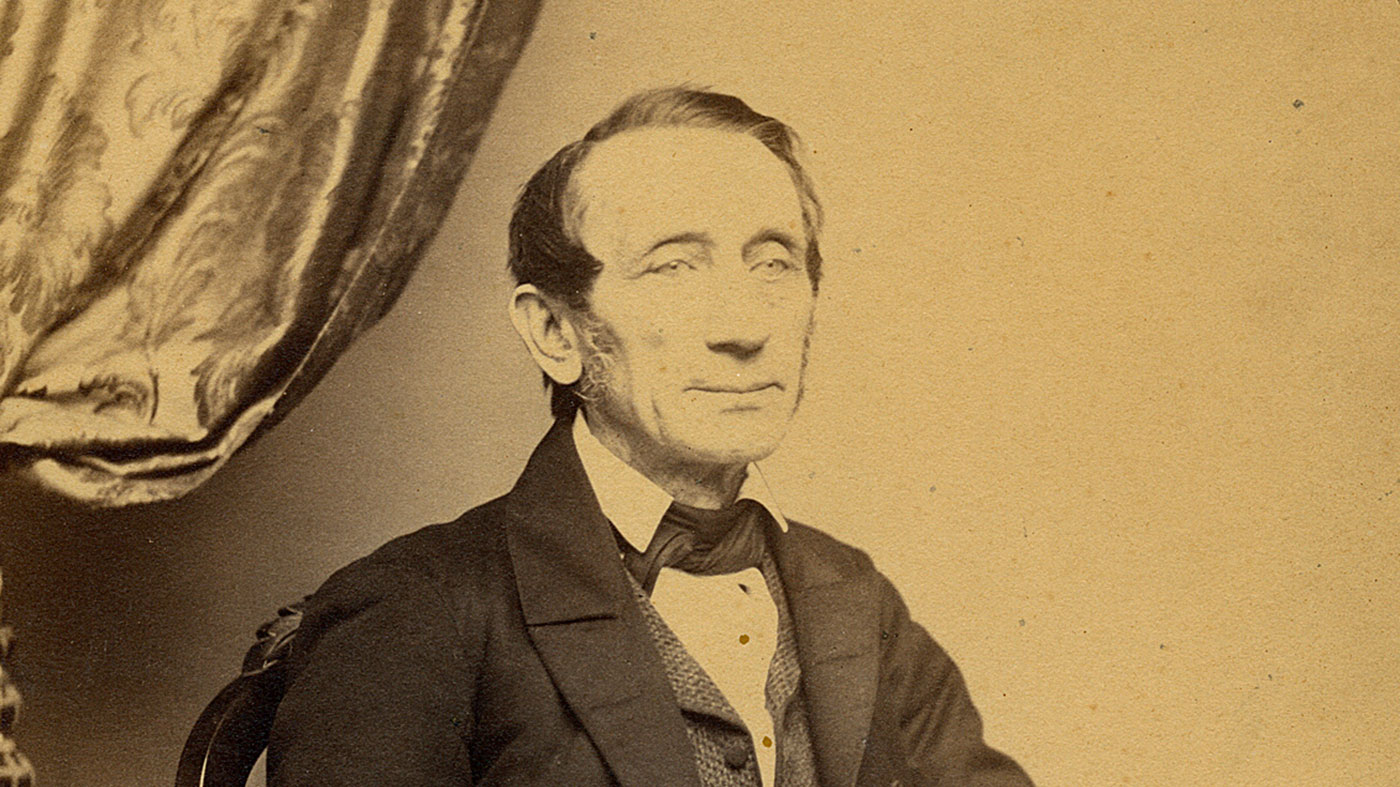

C.F. Martin was born in Markneukirchen, Germany, in 1796, and learned his trade from Viennese luthier Johann Stauffer. But when the time came for the apprentice to set up his own guitar-making business Christian Friedrich found his way blocked by a guild of violinmakers who lobbied local officials to prevent guitars being built by mere ‘mechanics’ - the derogatory term they used for anyone from a cabinet-making background who wanted to build instruments. So he emigrated to America, where he opened a shop in New York on 6 November 1833 and spent six years crafting fine instruments there.

The founder of the modern company studied luthiery under Johann Stauffer before establishing his own guitar shop in New York

He loved the work but his family disliked big city life. Around 1838, his wife visited friends in Pennsylvania, where she found a German expatriate community thriving in rolling farmlands much like those of Saxony.

This seemed the perfect ‘home from home’, so the family upped sticks again and moved to Nazareth, where they occupied a house and a small workshop that grew, as Martin’s fortunes waxed, into the sprawling brick-and-wood factory building that we stand before today.

The 175-year-old X-bracing design is still at the core of the Martin dreadnought voice today, but back then it was revolutionary

Though Martin stopped making guitars at North Street in 1964, the lower floor is still used as a warehouse for luthiery supplies, while the upper floors of the building have become an informal museum. Ushering us up the stairs, Martin employee Brendan Hackett shows us rows of original benches whose worksurfaces were worn concave by generations of Martin luthiers.

“Some of these benches were worked on for 100-plus years,” he comments as we wander round the rooms where everything from dreadnoughts to mandolins were built. As we explore the now-silent rooms that would have been noisy with the sound of steel on wood for over a century, a tool catches our eye. It’s a template showing exactly where the bracing - the struts of shaped spruce that support an acoustic guitar’s top - has to be glued into place for optimum tone.

“This represents the first, obvious piece in the puzzle of the modern-day Martin sound. C.F. Martin invented the famous X-pattern bracing between 1842 and 1843, well before the dreadnought was even dreamt of, incorporating it into his gutstringed Size 1 model. He built that guitar for Delores Nevares De Goñi, who was the most famous guitar soloist in America at the time. Thanks to Christian Friedrich’s innovative design, she declared Martins to be “superior to any instruments of the kind ever seen in this country or Europe for tone, workmanship and facility of execution.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Chris Martin, the company’s CEO, is the great-great-greatgrandson of founder C.F. Martin. Development of the new Reimagined Standard Series guitars was conducted with his input at every turn

But while X-bracing evidently worked well enough to impress Dolores, it was not in fact optimal for gut-stringed guitars and only rose to its full potential with the advent of steel-stringed Martins in the late 1920s. Its blend of strength and flexibility allowed the spruce top of the dreadnoughts, the ‘speaker’ of the guitar, to resonate freely enough to be loud and tone-rich - but was also robust enough to prevent a large-bodied guitar’s top from warping under the tension of heavy-gauge steel strings. This 175-year-old design feature is still at the core of the Martin dreadnought voice today, but back then it was revolutionary.

This delicate structure of wooden struts also symbolises the hardest challenge that guitar makers with a famous heritage face. Bold new ideas become received wisdom and finally timehonoured traditions. But the world moves on. Consumers want new guitars to live up to the reputation of the famous old Martins produced in the company’s early days. But those new guitars need to be produced in numbers that dwarf the output of yesteryear’s workshops. And many of the materials used in the grand old guitars of the past are much harder to get hold of today, too. So how do you keep the essence of the Martin sound intact while increasing playability, affordability and performance for modern guitarists, playing modern music?

New Tech, Old Style

Instrument Design Manager

Tim’s arguably got the toughest job at Martin: adding performance-enhancing technology to classic designs without changing their essence

We go looking for the answer a few blocks away from Martin’s old North Street home, in the company’s present-day factory. Here, laser cutters and high-spec CNC machines perform their precise work alongside luthiers handbending rosewood sides on heated formers very similar to the ones used 100 years ago. Look one way and you see a robot buffing a guitar body with inhuman precision. Look the other way and you see a craftsman shaping a neck with a tool that’s older than he is.

These Liquidmetal pins are very new... These alone give a 3-4dB increase in volume

On a balcony overlooking the bustling factory floor, sits a row of design offices. Inside, we find Tim Teel, who is Instrument Design Manager at Martin. He has to keep sight of how Martins are traditionally supposed to look, feel and sound, while trying to unlock extra performance from established designs.

To illustrate the point, Tim shows us a set of so-called Liquidmetal bridge pins. They look unobtrusive and even classic, but are made of a high-tech alloy that is exceptionally good at transferring energy from the vibrating string straight into the guitar.

“These are very new. These alone give a 3-4dB increase in volume. You definitely get an increase in sustain - but you don’t lose the rich bottom end of the tonal spectrum, as you would if they were aluminium. So it gives you all the really good attributes of a bone pin, but more so.”

The pins are going to be fitted to a new line of Martins that will be revealed in January, Tim says, along with other progressive features, such as titanium dual-action truss rods for lightness and composite bridge plates for yet more volume and sustain.

“We’re targeting these advanced materials to places on the guitar where they either provide a structural enhancement or a tonal enhancement that justifies them being there,” Tim explains. “But lot of the changes I bring in are either things that you don’t see - or when you do see them they look like they are still part of that classic guitar.”

D-28

But what about the essence of the original D-28, we ask? Has modern research uncovered why those 1930s dreadnoughts became so legendary for their sound and lasted so well? Tim said he found an important clue by reading the transcript of a speech on engineering made by C.F. Martin III - grandfather of Martin’s current CEO, Chris Martin - at a college, in which he described the traditional way that Martin prepared spruce tops for use back in the early 20th century. The method was slow in the extreme, but yielded great-sounding guitars.

From a structural standpoint, a guitar made with torrified wood is going to be more stable - changing seasons won’t affect its playability and tone so much

“The interesting part, for me, was when he described how they used to season wood,” Tim recalls. “Now, if you examine the cells of tonewoods like spruce, you’ll find heavy cellulose material inside that acts as a sponge. So it will take on moisture and it will release moisture, depending on atmospheric conditions, making the guitar less stable.

“So he said they would store their tops up in the rafters of the old factory, and a lot of times they didn’t touch them for five or 10 years. And those tops would go through all the seasonal changes. Bear in mind that in Pennsylvania we have wild swings of humidity, dryness and temperature. And over the course of those years, while that piece of spruce that was up there being seasoned, any heavy cellulose material that was in there would break down. And because of all those changes, some of the most stable guitar tops that are still around are from the 1920s, 30s and 40s. And they all went through that process.”

In other words, the passage of time and changing climate conditions made the spruce more resonant, lightweight and resistant to climatic changes when it was finally made into a guitar top. By these means, patience and old-world know-how produced results that have never been bettered. Needless to say, Tim and other Martin designers have devoted a lot of research to replicating the same effect in the present day - but without the necessity of seasoning wood in the roof of a building without air-conditioning for a decade. The answer they hit on was torrefaction: a process of carefully controlled kiln-baking.

“Torrefaction basically does the same thing as seasoning, but does it in a much quicker timeframe,” Tim says. “From a structural standpoint, a guitar made with torrified wood is going to be more stable - so changing seasons won’t affect its playability and tone so much. When it’s humid not only do some guitars play higher but the tone suffers quite a bit. Torrefaction deals with those two things.”

This became the tech behind Martin’s Vintage Tone System [VTS], which is used on selected Custom Shop models - but also Martin’s Authentic Series reissues. And the latter project marks where efforts to capture the original essence of the Martin sound really venture down the rabbit hole.

Time Machines

Vice President of Manufacturing

Jeff’s Martin’s resident expert on forensically accurate recreations of original vintage Martins, which form the basis of the stunning Authentic series

Jeff Allen knows a thing or two about old Martins. Along with Fred Greene, he was the driving force behind Martin’s Authentic Series of guitars. For the uninitiated, the Authentics are Martin’s most accurate recreations of hallowed models such as the 1936 D-45S. Martin now offer these in Aged versions, complete with painstaking lacquer checking and wear marks typical of 90-year-old guitars. They’re stunning instruments and near-perfect evocations of Martin’s revered pre-war guitars. Jeff formerly worked at both Fender and Gibson on their respective relic-ing programmes. He took the lessons he learned there about building aged guitars and brought them to Martin’s Custom Shop.

“The idea was to make the guitars sound and look closer to ‘Nirvana’,” he explains. “And to most guitar players, that would mean a 1937 D-28. So it’s not brand new, it’s old, it’s been played a lot, it’s dinged-up, it’s dirty, it’s cracked. It smells good and it sounds and feels amazing. So what we wanted was to find a way to recreate as many of those attributes on a brand-new guitar as we could.

What we really wanted was to target the ageing effect, so we could emulate tops made in the 1930s

“But I realised that before I could really do the ageing, I had to solve the issue with the top and with the bracing and how to age the wood. Because I knew I could make them look identical to the old ones. I’d already figured that part out from my time at Gibson and Fender. But I didn’t know if I could make them sound closer to the old guitars. And I thought, if I can’t make them sound like an old guitar then I’m wasting my time here.”

Like Tim Teel, Jeff realised that the answer lay in somehow imbuing the woods they were using with the character of old spruce tops.

“There was no way to make this guitar sound old with green wood: it’s just impossible. Or even 10-year-old spruce that had been downstairs in our acclimating room in perfect conditions for a decade. We built some test guitars from that and they still didn’t sound as close to an old ’37 as we wanted.

“So I kinda went back to the drawing board. One day I borrowed a microscope and I started looking at pieces of wood from a 1936 Martin that someone had sent back to us for repair. We keep all the old parts that we take off damaged vintage guitars, so I started collecting a stack of old spruce tops, all from the 30s. I started looking at the cell structure of every single one of them and then I compared them to the cell structure of some new torrefied spruce that Tim Teel had been working with. And I thought: ‘Man, this is not exact but it’s very close’.

“Although that was a good start, Tim and I soon realised that the industry standard torrefaction process was too aggressive. What we really wanted was to target the ageing effect, so we could emulate tops made in the 1930s. Not the equivalent of 200 years old, like you get with aggressive torrefaction - because while ageing like that does benefit the tone, the brittleness of the top becomes a risk factor: you might end up with bridges popping loose in 10 years or problems with cracking.

“So instead we thought: what if we could get it to where it sounded like a 1930s guitar? For some reason the 1930s remains the definitive decade, maybe because a lot of artists gravitate to those guitars and Martin made quite a few in the 30s. I don’t really have people calling me up and saying ‘I want a 1970s Martin’ or ‘an 1890s Martin’. They want the 1930s. So we started working with the vendors who torrify our tops. We couldn’t hit it immediately but after a year of tweaking the process, we had something very very close to a 90-year-old spruce top. We found we could make the cell structure so that if I didn’t tell you which one was the real old piece of spruce and which was brand new piece, you could not tell me which one was which. It was that good.”

History Reimagined

So by listening to voices from Martin’s past, then analysing the very fabric of the old guitars and finally applying new technology to the problem, Jeff Allen and his colleagues found a way to bring the sound of the legendary 1930s dreadnoughts back to life in Martin’s Authentic series guitars. But had they isolated the true source of the Martin sound? Well, while the results were impressive, they weren’t the whole answer because Martin have always had a knack for building a certain special sonic ‘something’ into all of their standard models, not just high-end reissues with torrefied woods.

Director of Product

Fred Greene is the man who carefully sifts trends in how players use guitars and devises new concepts for future guitars to meet musicians’ ever-evolving needs

However, it was clear that some of the construction hallmarks of the 1930s dreadnoughts that Tim and Jeff had examined in such close detail could also help Martin take their mainstream guitars to a higher level. This idea became the basis of the biggest overhaul of Martin’s Standard Line guitars since the 1980s - the Reimagined Series.

“The issue we ran into on the Standard Line was that we really hadn’t changed it much in quite a while,” Martin’s Director of Product Fred Greene recalls. “We worked on the D-18 a few years ago and people seemed to really like it. We went to a more modern neck shape and did a few other things. But we had avoided touching the rest of the line and it really hadn’t changed much since the 1980s.

Our dealers were competing with our own used product. So we knew we had to make some changes and we knew there were new players who wanted something different

“We’d built a million guitars in that time. So plenty of those guitars are out in the field and eventually our dealers were competing with our own used product. So we knew we had to make some changes and we knew there were new players who wanted something different.” The problem was where to start. Deciding what players might want from a 21st-century Martin was a potential minefield - stand still and other guitar brands gradually overtake you in terms of innovation and performance. But make changes that alter the familiar voice of landmark models such as the D-28 and you risk total disaster.

“We wanted to get the guitars to where they had a more modern feel but a vintage vibe at the same time,” Fred Greene says. “It’s a weird tightrope to walk. So we thought, ‘let’s look at what people ordered - what options are they choosing?’ And everybody wanted forward-shifted, scalloped bracing,” he says, referring to the bracing style used in pre-war Martins such as the 1932 D-28, in which the thickness of the bracing was pared back to a lightweight minimum and positioned quite far forward, which imparted extra-resonant properties to the top. Likewise, it turned out that the styling details that modern players liked most in retrophile 2018 were all out of the 1930s Martin catalogue, too.

“They wanted herringbone,” Fred continues. “They wanted binding that wasn’t bright, snowwhite binding. They almost always chose some kind of an open-gear tuner. One of the main reasons behind that is that open-gear tuners are lighter - they don’t make the guitar feel neckheavy. They also wanted to get rid of the gold foil logo, which felt very 90s, and they wanted to get rid of dot inlays - they wanted diamonds and squares instead.”

When it came to playability and feel, however, the situation was reversed.

“Oddly enough, they wanted the most modern neck profile we offer,” Fred says. “That’s our Performing Artist Taper neck. And so it was kind of a weird combination of old and new. We put all those combinations together on a guitar and looked at them [until we] said ‘that’s the way I would want my guitar’. The Martin brand is really a guitar player’s brand - they really own it. So you have to make decisions with them in mind.”

The Secret Sauce

Director, Custom Shop

Scott runs Martin’s dreamland R&D department: the Custom Shop. But the Shop also tackles small spec changes in standard guitars on request

So the leading edge of guitar design at Martin today is a taut blend of old and new. In fact, the ‘Yin and Yang’ struggle between tradition and change has been a feature of guitar-making here since the original C.F. Martin decided to leave hidebound Germany behind and set sail for America.

The only real constant is a shared idea of what a Martin guitar, new or old, ought to be. Get the formula right and devoted Martin players recognise it instantly, even if the design is brand new. Scott Sasser, director of Martin’s Custom Shop, took a pretty good shot at defining what the Martin sound means in everyday guitar-making terms:

We want to offer the greatest dynamic range possible in every body size

“We live in the world of organic materials and it’s difficult to talk in absolutes,” he says. “But we want to offer the greatest dynamic range possible in every body size,” he says. “It’s that breadth. No engineer ever complains about having too much volume. But being able to have that broad spectrum of tonality, that’s what helps a guitar move and breathe.”

Dynamic range is certainly a big part of the Martin magic, but arguably it’s more subtle than that. The technology that helps the luthiers evoke the Martin sound may change over time, but the goal remains the same. It’s a thought that strikes us afresh as we watch Brendan Hackett examine a spruce top for hidden flaws by shining a light through it with a ‘candling’ machine. Though cutting-edge equipment aids the process, the luthier’s eye still scans the grain for faults with the same careful scrutiny as in the days of the classic 30s dreadnoughts. And this institutional knowledge is where the real continuity in Martin’s sound comes from.

Down on the factory floor, when a job needs to be done that requires feel, experience and careful judgement there’s a person, not a machine, wielding the tool. And some of the people working here belong to families that have worked at Martin for generations, passing along the skills to sons and daughters. That shared experience, stretching back through the decades, leaves its mark on every aspect of how all guitars are made here, not just the high-end stuff. And thus the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. As we were passing through the old factory on North Street, our guide Brendan remarked that some of the antique tools on display were only retired from factory use six years ago. Martin’s like that: nothing useful is ever thrown away.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.

“For those on the hunt for a great quality 12-string electro-acoustic that won’t break the bank, it's a no-brainer”: Martin X Series Remastered D-X2E Brazilian 12-String review

“Beyond its beauty, the cocobolo contributes to the guitar’s overall projection and sustain”: Cort’s stunning new Gold Series acoustic is a love letter to an exotic tone wood