808s, MPCs and Auto-Tune: The story of hip-hop production in 10 iconic bits of gear

Hip-hop's evolution is intertwined at every turn with the development of music technology. As the genre turns 50, we chart its five-decade history through ten influential pieces of music-making kit

This year, hip-hop celebrates its 50th birthday. Far more than just a style of music, hip-hop is a cultural universe, filled with art, dance, sound and poetry, the influence of which has spread from the block parties of the Bronx across the entire globe. Even after five decades, hip-hop remains at the beating heart of the bleeding edge.

But where would hip-hop music be without the gear used to make it? The radical ingenuity of artists, beatmakers and producers working in hip-hop has taken humble pieces of equipment and adapted, repurposed and reimagined them to create new and innovative sounds that they were never designed for.

The visionary methods of hip-hop producers and DJs have changed the way manufacturers make gear, as they began to cater to the artists who ended up showing them how it should be done - and we’re all the better off for it. Join us as we revisit ten iconic bits of gear that defined the story and the sound of hip-hop...

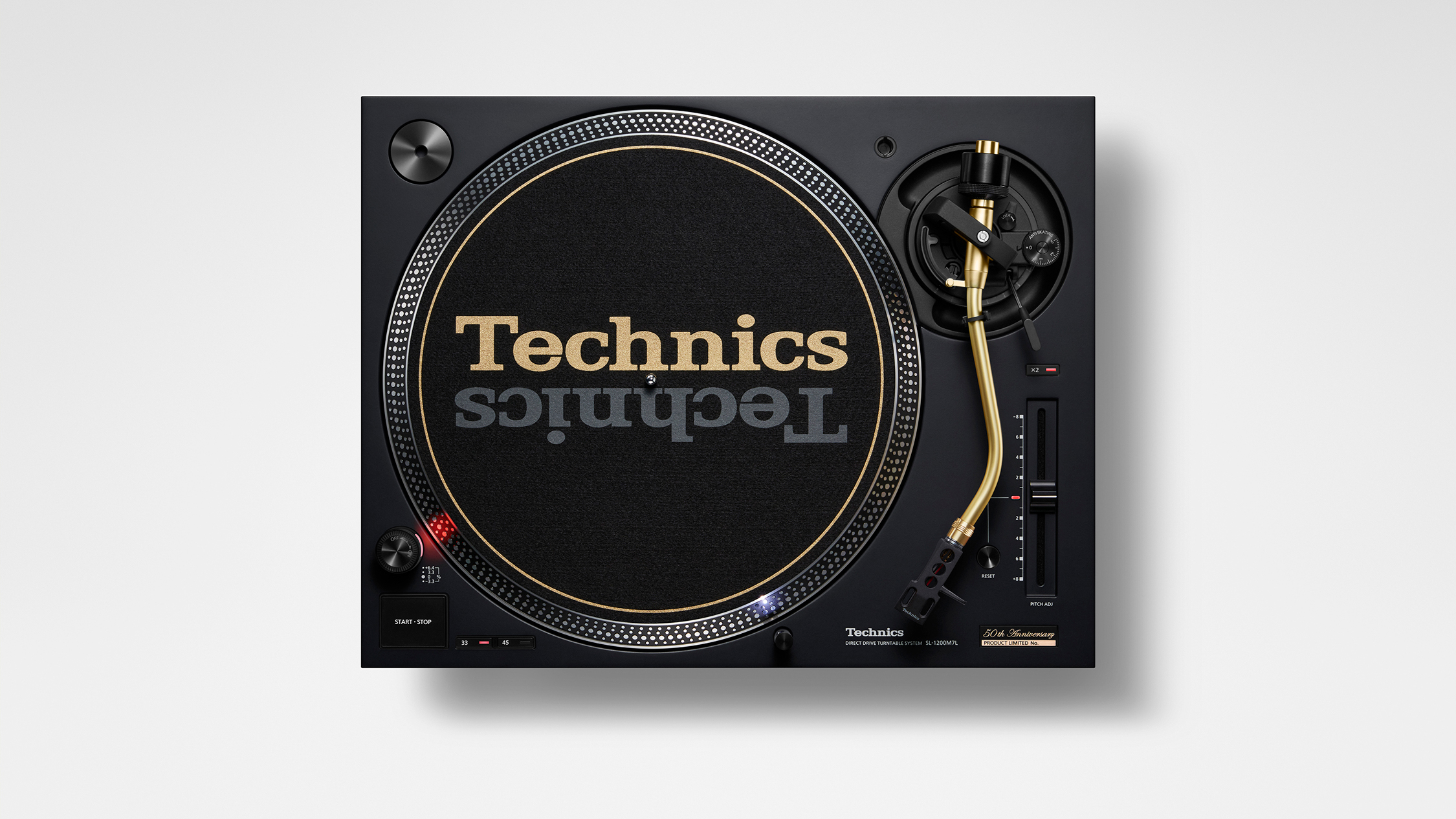

1. Technics SL-1200

The Technics SL-1200, released in 1971, is the grandfather of unquestionably the most famous turntable series of all time. Key to its innovation was its high-torque, direct drive brushless motor; compared to the more common belt-driven platters of turntables of the era, the ability to directly manipulate the platter and have it immediately react and regain its target speed was a revelation.

Without this ability to get hands-on with vinyl records, hip-hop forefather DJ Kool Herc may never have ingeniously discovered how to use the turntable as an instrument in its own right, manipulating breakbeats into collages of looped and layered patterns. Grand Wizzard Theodore might not have been inspired to manipulate the record itself while it was spinning on the platter, creating the first scratches.

Technics at 50: how the SL-1200 series accidentally changed music forever

The MK II revision, released in 1979, was a completely revamped design that found near-universal favour with DJs for three key reasons: it featured excellent sound isolation that could absorb loud environmental sounds and vibrations from tables without transferring them through the stylus, the motor stability was further improved with quartz timing, and it allowed for speed adjustment via an accurate pitch slider. Beyond that, the SL-1200 MK II is a masterpiece of engineering, virtually bombproof in its design. Oh, and the brushless motor patent didn’t hurt in staving off copycats, either.

An honourable mention to Vestax - and its advancements in pitch and torque lending even more control to scratch DJs - notwithstanding, the Technics SL-1200 MK II remains the blueprint for what a turntable should be for anyone that intends to use it as an instrument in its own right. There’s even one in the National Museum of American History, donated by none other than Grandmaster Flash himself!

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

2. Shure M44-7

It’s all well and good having a turntable that can handle the demands of a scratch DJ, but if the needle won’t stay in the record it’s all for nothing. Enter the Shure M44-7 cartridge (and N-447 stylus): originally conceived to cope with the demands of vertical-loading vinyl jukeboxes, it’s loud, punchy, low-wear, and sticks to records like glue.

Without the M-447, scratching may not have developed into the expressive art form that it's become today. More than that, though, the volume, fantastic bass response, punchy sound and slightly abrasive highs of the M44-7 created a sound that subliminally shaped the character of parties and mixtapes for decades.

The M-447 was ultimately discontinued in 2018 along with all of Shure’s phono product line, but as testament to its popularity, a cottage industry of third-party compatibles has sprung up in its place.

3. Oberheim DMX

Only just missing out on the crown of first digital drum machine - that goes to the Linn LM-1 - the 1980 release of the Oberheim DMX nevertheless ushered in a new era of production. The ability of the DMX's sound to instantly transport you to an era of music gone by stands as a testament to how important its place in musical history really is.

Fab Five Freddy’s Change the Beat, Run DMC’s It’s Like That and Sucker MCs, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s The Message and White Lines, Beastie Boys’ The New Style, Slick Rick’s Mona Lisa… the DMX was the beat for a golden era of hip-hop.

With just 11 samples tuned into 24 sounds, it’s little wonder that the DMX is so instantly recognisable. Samples could be swapped with removable voice cards, but these were expensive and by all accounts difficult to obtain, so stock sounds were the ones most artists used.

In any case, the DMX’s capabilities were higher and its $2900 launch price significantly lower than the $5000 Linn LM-1, and the 1983 release of the feature-reduced DX for $1400 cemented its place as the go-to realistic drum machine for hip-hop producers, until sampling drum machines began to take over.

4. Roland TR-808

Van Gogh died penniless. The Roland TR-808 was originally a commercial flop. Van Gogh’s Orchard with Cypresses recently sold for $117m, and if you’re in the market for one of the 12,000 808s Roland produced between 1980 and 1982 (before it was discontinued) you can expect to pay in the region of $5000. There’s no doubt that the heritage of the machine is a large part of the price it commands amongst artists and collectors, but… what a heritage.

After its fully analogue sound capabilities were utilized in 1982’s Planet Rock by Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force, the TR-808 landed on the map in a big way. That thunderous bass drum, snappy snare, crisp clap and distinctive cowbell are amongst the most recognisable sounds in music history, and a booming sub bass hit is now called an 808 in the same way vacuuming your carpet is known as hoovering.

Sounds from the TR-808 have been sampled and processed as a key part of the language of hip-hop drums since the 1980s, notably as a core component of the dirty south and trap soundscape - and lest we forget Kanye West’s 2008 808s and Heartbreak, a record that helped - if not single-handedly - set the path for the 808 sound to once again dominate the mainstream sound of hip-hop to this day.

5. E-mu SP-1200/SP-12

Whilst perhaps not the first, the EMU SP-12 almost certainly takes the crown as the first viable sampling drum machine. Released in 1985, the SP-12 was quickly updated into the SP-1200 by 1987, an upgrade that took sampling time from 1.5 seconds (upgradable to 5 seconds with the ‘Turbo’ upgrade) to 10 seconds.

The SP-1200, sounding and operating in the same way just with more memory, is the version with the most hits under its belt, but hip-hop producers like Prince Paul of De La Soul caught on to the SP-12’s potential from the get-go. The unit’s 27.5KHz sample rate (26KHz on the SP-1200 to accommodate the larger sample memory, but with essentially no discernible difference in character) lends it a gritty, aliased sound.

To maximise the meagre sampling time and enable them to record not just drums, but entire melodic phrases, producers began to record samples from vinyl at high speeds and pitch them down, further crunching the resolution and accentuating the instantly recognisable lo-fi ring that’s graced so many classic records. It’s a familiar tale in hip-hop: see a limitation and turn it into a strength.

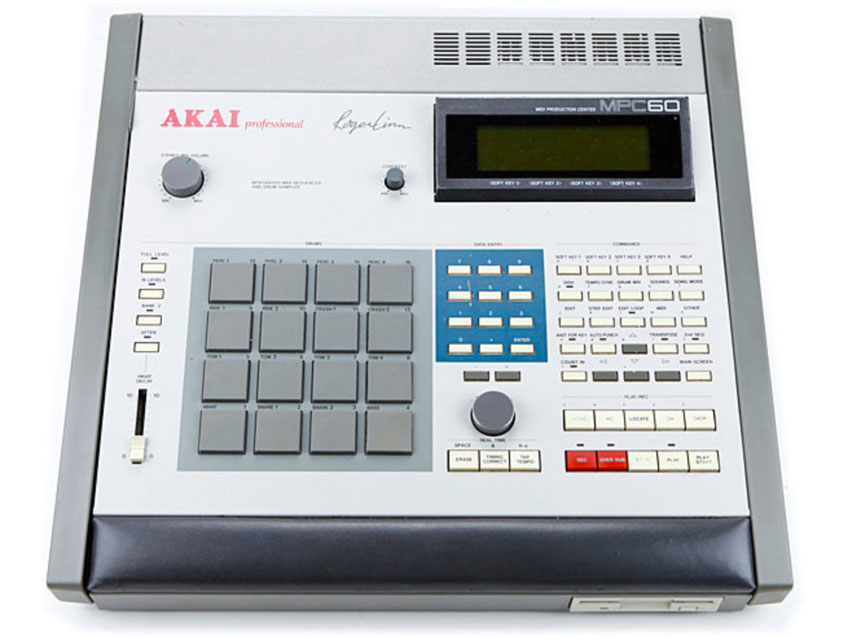

6. Akai MPC60

The venerable MPC. The MIDI Production Center, later Music Production Center, is as iconic a piece of gear as anything we could mention. Those 16 pads, laid out in four rows of four, might have become as fundamentally recognisable as the piano keyboard at this point — and it was the MPC that started it all. The MPC60, to be precise, was the first, released in 1988 and swiftly ushering in a new era of beats.

The brainchild of Roger Linn, the man that developed the first sampling drum machine - the aforementioned Linn LM-1 - the MPC60 was truly innovative in ways that have shaped what it means to be a ‘groovebox’ to this day. Combining sampling and sequencing, the MPC stripped away complicated sampler patch parameters and provided users with a speedy, just-get-it-done workflow ideally suited to drums.

Originally conceived as a drum-focused unit, the MPC60’s electronics were selected and tuned for punch, and the 12-bit 40KHz sampling kept the crispness of hi-hats while lending pleasing thickness to kicks. The built-in sequencer and 13 second — (upgradable to a huge-for-the-time 26 second) — sampling time made it the perfect machine for hip-hop producers to sample entire melodic phrases into it though, and before long many, including DJ Premier, Hank Shocklee, and Prince Paul were defining an entirely new, more hi-fi and sophisticated sound for hip-hop throughout the end of the '80s and into the '90s.

Oh, and of course we have to mention the classic MPC swing. Spoken of in reverent terms for years, even its creator Roger Linn has stated that it’s just a simple percentage shifting of the evenly numbered 16th notes towards (and beyond) triplet timing — but whatever the magic is, it’s responsible for uncountable head-nodding grooves.

7. Ensoniq ASR-10

It’s not as widely known as the MPC or the SP1200, but the ASR-10 was and is the device of choice for the producers behind hundreds of classic records. Kanye West, Timbaland, and The Alchemist all favoured the ASR-10 for a decent chunk of their careers — and aside from its 1992 launch, with CD-quality 44.1KHz 16-bit sampling that predated the MPC3000’s claim to the same throne by two years, the nuances of its functionality allowed records to be made in ways that just weren’t possible on the MPC.

Available in both rackmount and keyboard form (with the keyboard being the more popular unit) the way the ASR-10 allowed for samples to be referenced with different start and end points on a per-key basis facilitated a non-destructive chopping workflow. In the words of Kanye West: “The reason why I use it […] is because you can chop into 61 samples without wasting no memory”. Furthermore, the significantly more advanced and involved effects and patching capability of the ASR-10 compared to the MPC range allowed beatmakers and producers to have a single keyboard for their entire production workflow.

Few producers defined a stake in hip-hop like Timbaland, who wrote “the very first one I did all my hits on” against a picture of an ASR-10 on his Instagram. Classic studio videos show Timbland playing Ludacris’s Potion and Jay Z’s Dirt Off Your Shoulder, he and Kanye West deliberating over the drums for Kanye’s Stronger, and Kanye creating a peak-chipmunk-soul-era Kanye West beat, Do or Die’s Paid the Price, all on ASR-10 keyboards.

8. Korg Triton

By the late '80s and throughout most of the '90s, sample-based beats had become the backbone of the hip-hop sound. There was a growing problem, though: the wild-west era of sampling without consequence was coming to an end, and the platinum potential of a hip-hop hit was turning sample clearance into a very expensive pursuit.

Whether driven by a response to the risk of samples slicing into the royalties of a song or simply a desire to move in a new direction, synth, sound module, and keyboard workstation-based hip-hop records began to grow increasingly common by the late ‘90s and pretty much dominated the radio by the 2000s — and the Korg Triton, released in 1999, became the source of some of the most recognisable hip-hop records of all time.

Pharrell Williams defined an entirely new direction for hip-hop in the opening decade of the new millennium, and the sound of the Triton was front and centre in countless productions from Clipse’s Grindin’ to Nore’s Nothin’, Jay Z’s Excuse Me Miss, facilitating the crossover R&B sound of Justin Timberlake’s Rock Your Body… the list goes on.

9. Boss SP-303/Roland SP-404

It’s 2002, and Madlib’s in a hotel room in Brazil. “I’m gonna have four beat tapes when I leave” he says, and points at an SP-303 on the table. “With that — everyone’s sleeping on it”. They weren’t sleeping for much longer, though. If any more endorsement were required, legend has it that J Dilla created the majority of his final album, the legendary Donuts, from a hospital bed — on the SP-303.

The squashed, ultra-glued and roughly collaged sound that defined Stones Throw Records’s hip-hop output in the 2000s has the Boss SP-303 (and later the SP-404, after Roland bought up Boss and released its big brother) to thank. Both units are small samplers with seemingly modest capabilities and rudimentary displays that can only show a few digits, not even the ability to save projects in a conventional sense. It’s their ability to reference as much audio as can fit on a memory card, a varied set of effects, and performance-focused resampling that turn beatmaking on an SP-303 and SP-404 into an organic, intuitive process.

And the effects… if we’re talking gear that defined hip-hop, then a certain corner of lo-fi-flavoured hip-hop basically IS the SP-303 and SP-404’s compressor and vinyl sim effects. The LA beats scene, championed by historic night Low End Theory, was a hive of the pumping, unstable, head-knocking sound that these effects produced, and whether or not it came from an SP-303 or was achieved elsewhere, it’s one of the most recognisable production techniques, indisputably borne from Roland’s humble samplers.

10. Antares Auto-Tune

Cher may have brought it into popular consciousness in 1998, but wilfully abusing Auto-Tune - originally conceived by Antares and since imitated by many a competitor - has become a hip-hop staple.

In 2005, T-Pain exploded onto the airwaves, at a time where hip-hop and R&B crossover was at its commercial peak. Lil Wayne’s affinity for the effect, which melded captivatingly with his drawling, southern flow, paved the way for an era many - perhaps most - are relieved has fallen out of the commercial limelight: ‘mumble rap’. With Auto-Tune’s ability to impart musicality into any signal fed into it, suddenly the ability to sing or rap with any tuning, cadence, or even intelligible content was a bonus, not a requirement.

Despite Jay Z taking his best shot in 2009’s Death of Auto-Tune, the plugin has endured, its usage in popular music developing into a more subtle, musical complement in the years since, while going on to inspire adventurous artists like Bon Iver, Frank Ocean and Lisel and to radically manipulate their voices in creative and experimental ways.

Chris has been making music since 1997 when the box for Mixman Studio Pro called out to him at HMV — the perfect time to watch VSTs get introduced to the world and the computer music revolution gain speed. His experience of producing and performing in the worlds of hip-hop, turntablism, and electronic music saw him featured in legendary publications Hip Hop Connection and RWD, tutoring and managing organisations dedicated to introducing music-making in the community, creating, writing and editing for leading DJ and music production websites during the digital boom, and he now runs howtomakemusic.co from his studio.