New year, new track: 50 ways to kickstart your next track in 2023

Overcome writer’s block and create your freshest ideas yet with our bumper pack of inspiration-sparking tips and tricks

When you’re inspired, the creation of electronic music can feel effortless. Every sample you select is the perfect one, falling into place on your DAW’s timeline like magic.

Firing up and triggering a synth instantly inspires a bassline or hook. MIDI notes and audio build up to create a composition you never could’ve planned. Once those creative juices are fully flowing, it feels like the music is writing itself.

If you’ve experienced this zen-like state, you’ve probably been through the complete opposite, too: those times when a blank screen remains overwhelmingly empty, and every technique is doomed to fail. The harder you push against this creative drought, the more stress builds up.

If you do push past this ‘writer’s block’ somehow, you can end up with a track that has all of the functional elements of a track (drums, bass, chords, etc), but lacks the spark and magic of something truly special.

Though there’s an art to making music, us electronic musicians are lucky in that we have technology on hand to help us. The secret is recognising when your gear – hardware or software – is hindering your creativity, then hacking that tech to get around the problem.

In this feature, we’re here to help you beat the block and create your best ideas ever. To that end, we have creative challenges for you to try, gear ideas to inspire new sounds, and insight from a multitude of artists on how they like to begin their projects. But first…

Where to start?

Let’s start with the basics – where exactly should you start your next track? It sounds like a simple question, but there are so many potential answers that paralysis of choice – ie, being confronted with so many options that it’s impossible to pick one – can be a real issue.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

What was the starting point for your last track? Take that and flip it on its head

Do you start with an intro and build up as the song progresses, or start in the middle, creating your fullest element – the drop, hook or chorus – and then work subtractively? Do you start with drums first and nail a rhythm, or create a melody and build from there?

There are, obviously, no right or wrong answers to this, and often we’re fortunate enough that inspiration will strike us and the whole process comes naturally. For times when this isn’t the case though, there are a number of tactics we can employ.

The first is to mix things up. What was the starting point for your last track? Take that and flip it on its head. If you usually tackle drums first, write some melodies, if you last started with a drop, try creating an intro or breakdown first.

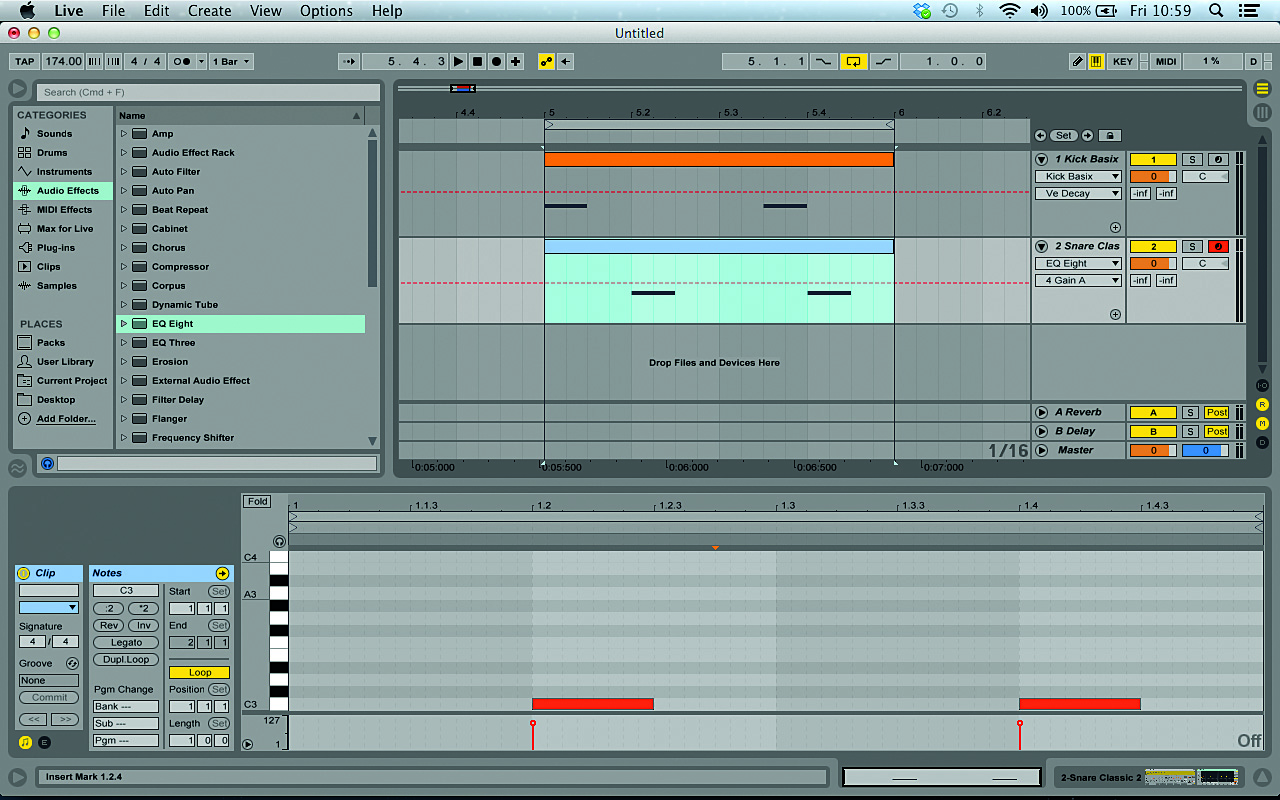

An empty DAW project can be daunting. Try preparing a template for your project before you begin

Another reliable way to overcome a creative blockage is to avoid the blank canvas. An empty DAW project can be daunting. Try preparing a template for your project before you begin, with commonly used instruments and effect sends in place.

Perhaps even sketch out a template arrangement with MIDI clips. You could also try creating an ambience or backdrop, with some found sounds or a lingering drone, to give your creations a little context and not seem so exposed.

Let the machines do the work

When you’re in a creative lull in the studio, judge whether the technology at your disposal is helping or hindering you. Having a small selection of hardware and software tools you know inside and out will help to narrow down your palette of options, but even then, you’ll probably have more options than you actually need.

One way to ‘defeat the machines’ is by working out how you can use them to assist the compositional process. Strip things back and give these five creative approaches a go…

1. Varying arpeggiations

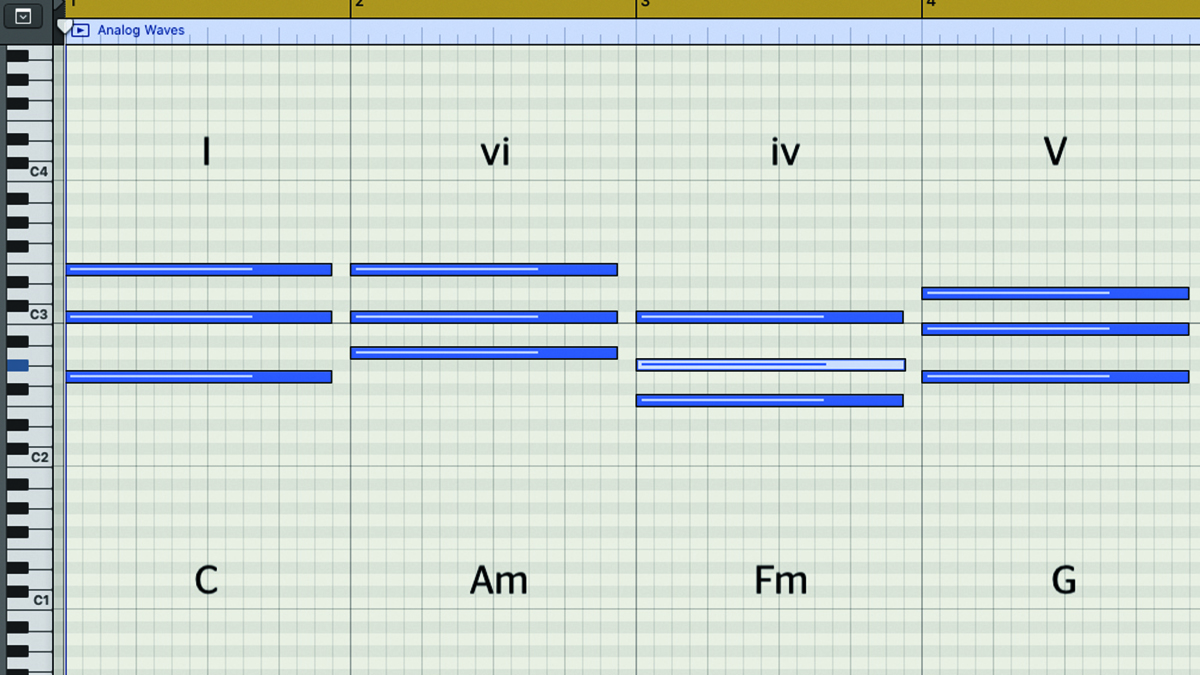

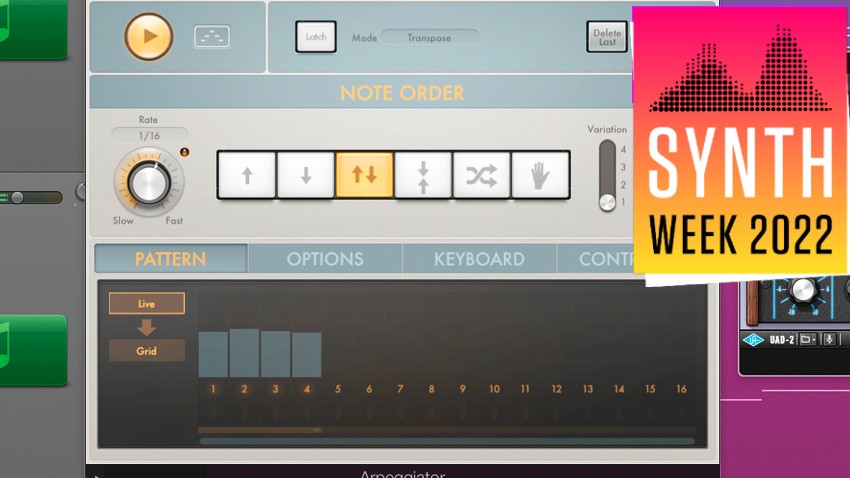

Arpeggiators can be great tools for turning a simple chord progression into something with more rhythmic interest. By layering multiple arpeggiated instruments on top of one another, it can be possible to inspire more than just a single line, and potentially create enough elements for a full track.

Start by creating a simple chord progression and arpeggiator, then copy this across two or more MIDI tracks in your DAW. The trick is to change the parameters of each arp to create different patterns that interact with one another.

One could be in a straight 4/4 rhythm, but another in triplets? One could travel downwards, while the other goes up? Try pitching a copy of your main arp line up an octave or two and then randomising the pattern. You could even feed an arp into a drum machine to create a rhythm track.

2. Slice and edit

Got a loop or melody you like but aren’t that inspired by? Grab a sampler and slice it, using, say, Ableton’s Slice to MIDI or Logic’s Quick Sampler slice mode. This will let you rearrange the original loop as a MIDI file until you find a rhythm or pattern that grabs you. Try using a step sequencer or arpeggiator to help you flip the original loop on its head.

3. Self-sequencing synth

Try designing a synth patch that does all the work for you. We’re referring to those kinds of presets that sound like an entire track at the push of a button. By combining multiple oscillators, LFO-driven noise rhythms and other tones, all running at different rates and speeds, you can generate uber-complex sounds that can define an entire tune.

Modular synths are ideal for this, both in the hardware or software realms. Anything that lets you freely route rhythm-generating elements like LFOs, looping envelopes, clock dividers or sequencers. VCV Rack provides an excellent way to explore these ideas for free in software.

4. Simple synths, complex effects

We often devote a lot of our creative energies to designing or recording sounds, then use effects for a final polish. Try flipping this dynamic on its head though, by taking a simple sound source – say, a sine wave, kick drum or simple piano chord – and using a complex chain of effects to completely reshape it.

Stacking multiple delays with a wet/dry setting over 50% can turn a single hit into a whole rhythmic pattern, and pitchshifting can transform a melodic line too. Tools such as comb filters, resonators or extreme reverbs can utterly transform even a basic sound into something epic and inspiring.

5. Probability and randomisation

Ordered chaos: a guide to randomisation, probability and generative music

Probability sequencing is everywhere these days, from DAWs like Live and Bitwig to hardware from Elektron, Korg, Novation and many others. These are great tools for inspiring new sequences. Create a pattern where the root note has a 100% probability but everything else has something less, meaning your pattern will change a little with each cycle. Let the sequencer run and record the results, then edit out and keep your favourite variations.

Creative challenges

When you sit down in front of an empty DAW, your creativity can often feel stifled by the overwhelming number of options you can choose from. A producer’s hard drive is typically stuffed full of dozens, or even hundreds, of virtual instruments, sample packs and processing plugins. And that’s not counting the myriad of hardware synths and outboard gear that are all plugged in and ready to go.

The secret to overcoming ‘decision paralysis’ is to impose some kind of creative limitation designed to rewire your thinking

The secret to overcoming this ‘decision paralysis’ is to firstly recognise that it’s a problem, then impose some kind of creative limitation designed to rewire your thinking. After all, back in the day, producers and engineers were limited by the primitive gear they had to hand, and worked around low track counts and meagre sampler channels to wring every possibility out of less gear.

6. Get off the grid

Feeling restricted to a grid? Then try working with quantisation completely disengaged, and place all your hits by ear. This’ll help get you away from your usual formulas and encourage some new ideas.

7. Less is more

It’s all too easy to pile up unlimited audio and MIDI tracks in a modern DAW, which is why you should regularly practise making tracks with super-low track counts. Capping yourself to, say, four or eight tracks in a project forces you to wring the most out of every sound.

Give yourself a hard limit and, if you need to add something more, find a creative way to work around it. Perhaps you could save space by bouncing several parts down to a single bus track, then process and edit them as one? Or find a way to use a single plugin instance or hardware instrument to generate multiple sound elements, such as synthesising both a kick and snare.

8. Single synth session

Why not try making an entire track using only one drum machine or synth? Not only will this make you think creatively about how it can be used, but you’ll also grasp the instrument’s nuances and learn it a bit better. This approach can be a great way to flex the sonic muscles of a synth you know really well, but it’s even better when applied to a new or underused bit of gear.

Got a plugin on your hard drive that you picked up cheap and never really explored? Or an unloved synth that’s been gathering dust? This could be the perfect time to dive in and explore what it can really do. Read the manual front-to-back and really dig into the capabilities of what your chosen instrument can do.

9. Recreate, then remix

Nobody wants to plagiarise another musician’s work, but it’s also true that inspiration doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Every great idea in the history of music is on some level built on whatever’s come before it. There’s no shame in using a track you admire as a jumping off point for your own ideas.

There’s no shame in using a track you admire as a jumping off point for your own ideas

If you’re stuck for where to begin, rather than creating a track of your own from the ground up, try recreating an existing track and then reconfiguring it to make it your own. Load up a reference track in your DAW and go through recreating it as best you can, piece-by-piece. Once you’ve got an approximation of a full track – effectively a demo cover version – it’s time for the fun to begin.

Edit, rearrange and remix until you have something far enough away from the original inspiration that nobody could identify your source material. Adjust melodies, reconfigure track elements and swap out sounds for something completely different.

10. DJ tool

Necessity is the mother of invention, and one great way to inspire your next track is to try and write something to fit a specific need. That could be a tool to fit somewhere into a DJ set – such as the perfect peak time banger, a loopy groove that’s easy to mix over, or a track designed to help shift the mood or tempo.

The same principle can be applied if you’re a live performer. Try writing a great set opener or closer. Don’t DJ or perform yourself? Pick a favourite artist and try and create something as if you’re pitching it directly to them.

11. Switch up your approach to playing or programming

How do you usually start a track? Maybe by playing chords on a keyboard, using a hardware sequencer, or drawing beats onto a MIDI grid? For your next track, try banning yourself from composing in your usual manner and adopting a different approach. Try switching out your usual keyboard for a pad controller like a Novation Launchpad or Ableton Push.

Got an old guitar gathering dust in the corner? Use that to write your next chord progression instead of your go-to synth. Do you usually create MIDI patterns in your DAW? Try using a hardware step sequencer, or a plugin emulation.

12. Sample flips

How about picking one sample pack based on a completely different genre to the one that you produce? If you happen to be a techno producer, for example, why not try restricting yourself to creating a track using sounds from a reggae or drum & bass sample pack? See how you can reshape the sounds to fit your own style – or let them take you off in a completely new direction.

13. Preset ban

Presets can be incredibly useful. It can, however, be a little too easy to settle into a rut of reaching for your favourite go-to sounds and patches. For your next project, try an outright ban on presets.

Presets can be incredibly useful, but it can be a little too easy to settle into a rut of reaching for your favourite go-to sounds

Whether you’re using hardware or software, start from an initialised state and build your sounds up from scratch. The same goes for effect treatments – ditch those tried and tested compressor settings, delay treatments and reverb patches and shape your sounds by ear from the ground up.

Idea-generating plugins

14. Audiomodern Playbeat

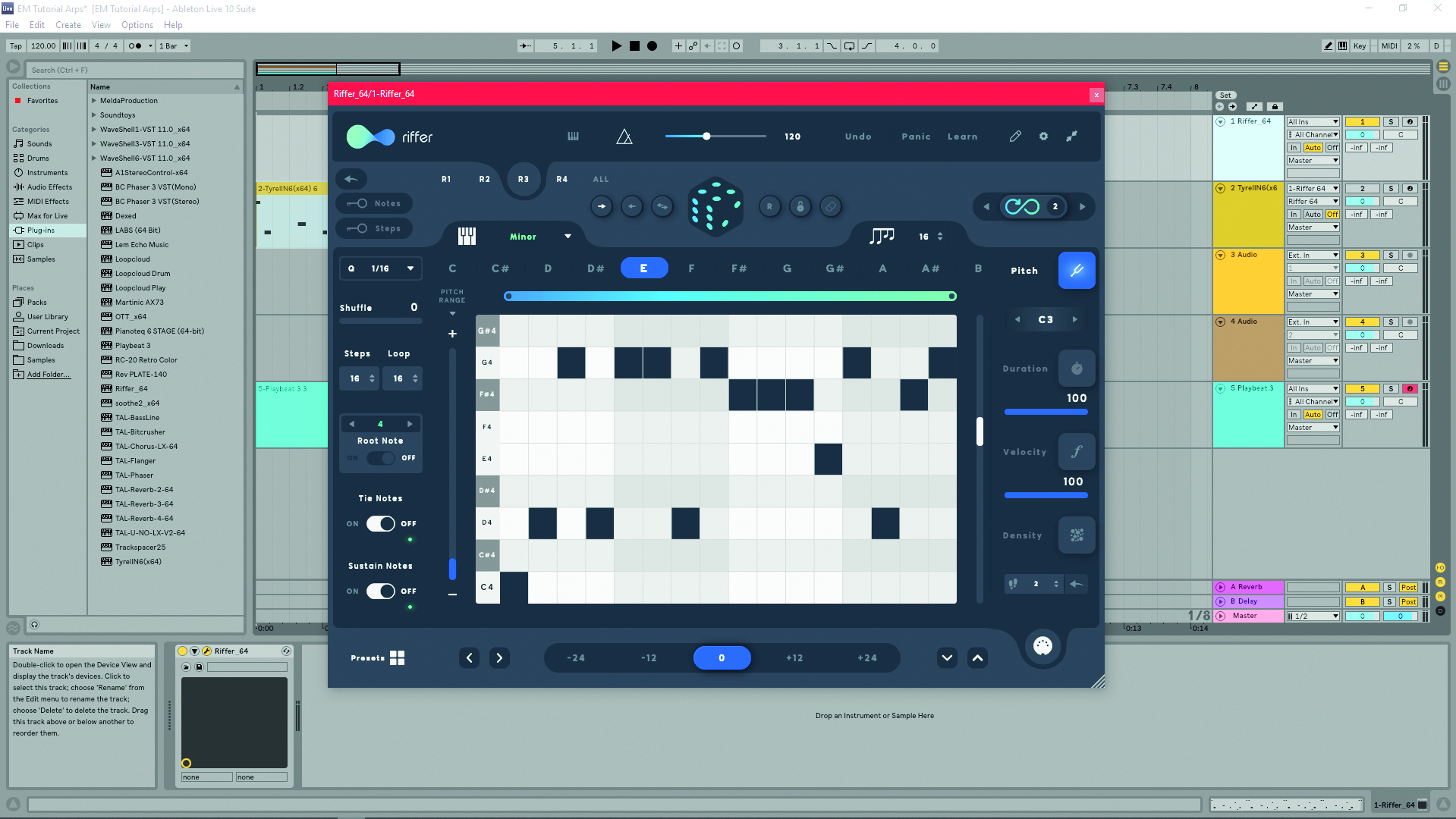

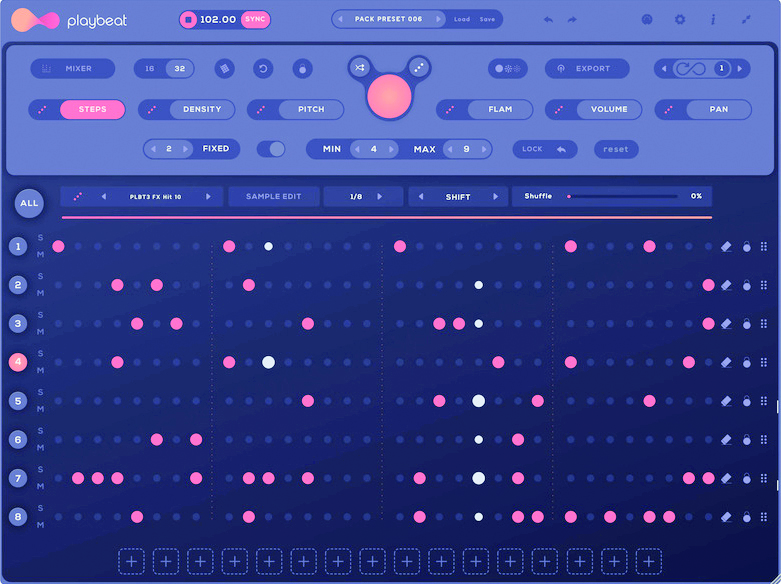

Recent years have seen a rapid rise in plugins that auto-generate elements of your track. While Mixed in Key offer useful tools, Audiomodern’s plugins are some of the best. Playbeat, Chordjam and Riffer aim to help you create new ideas, each focused on a different track element – drum patterns, chord progressions and bass/lead riffs.

What marks these plugins out is the balance they strike between ‘doing it for you’ and offering tools that let you shape the generative process. Playbeat offers fine control over which beat elements get randomised, and learns from your creative decisions.

15. XLN Audio XO

XO is an innovative beatmaker that aims to help you discover forgotten or overlooked corners of your sample collection. The idea is that users add all of their one-shot samples, which are then analysed in order to create a ‘space’ that maps them all by timbral qualities and style.

Why is this inspiring? The key appeal is that it will help you branch out from your go-to drum hits and percussion tones by quickly browsing through similar samples, even if these are stored in completely separate folders.

16. Entonal Studio

‘Microtonal’ is a bit of a buzzword in music production these days, but it’s nothing new – Aphex Twin were making microtonal sounds in the ’90s, and classic composers have been exploring microtonal ideas for centuries.

Microtonality involves using intervals smaller than semitones – ie, moving away from the traditional western 12 tone chromatic scale. Sound complex? Well the good news is Entonal Studio makes experimenting with microtonality easy. It can host your favourite synth plugins, turning them into microtonal instruments, and has a clear UI and plenty of presets to experiment with.

17. Korg Wavestate/Opsix/Modwave

Korg’s trio of digital synths are some of our favourite hardware instruments of recent years, and they’re now all available in your DAW in ‘native’ plugin form. The key feature in all three is the patch randomisation tools. Effectively, these allow the user to roll the dice and randomise all parameters in the sound engine.

Does this always sound good? No. But it’s easy enough to take another spin and keep going until you hit on something inspiring. The process can be tailored to focus on just specific elements or ranges too, meaning the randomisation can be far better targeted.

18. Output Portal

Granular processors are particularly good sources of sonic inspiration, since they span the remit between creative sampling and delay, meaning they can transform sounds both in terms of pitch and rhythm.

There’s a multitude of quality options worth trying in this sphere, including the Max for Live plugin Granulator 2 and Arturia’s recent EFX Fragments. If we had to pick one granular tool that’s especially good for quick inspiration though, it would be Output’s Portal, which benefits from an approachable UI and excellent list of varied presets.

Chord-striking theory ideas

Even if we’re not all virtuosic players, most of us can string a few simple chords together to get a basic melodic idea down. The hard part, sometimes, can be moving from a pleasant but basic progression to something that can form the body of a track. Try spicing up your ideas with these simple tips.

Here are five quick theory ideas to improve your progressions…

19. Try a new time signature

Would you be disappointed if you were only allowed to write in C minor from now on? Of course you would. The limitations of everything playing back in the same key would start to feel stale.

How to create beats in different time signatures in your DAW

And yet, nearly every piece of commercial music you’ve ever heard is in 4/4. It’s a de facto choice for most people; almost always the default choice in every DAW. Break out! Switch the time signature in your project to 3/4 or 12/8 or even 5/4 and see what happens. You’ll feel much freer to program innovative beats, for a start.

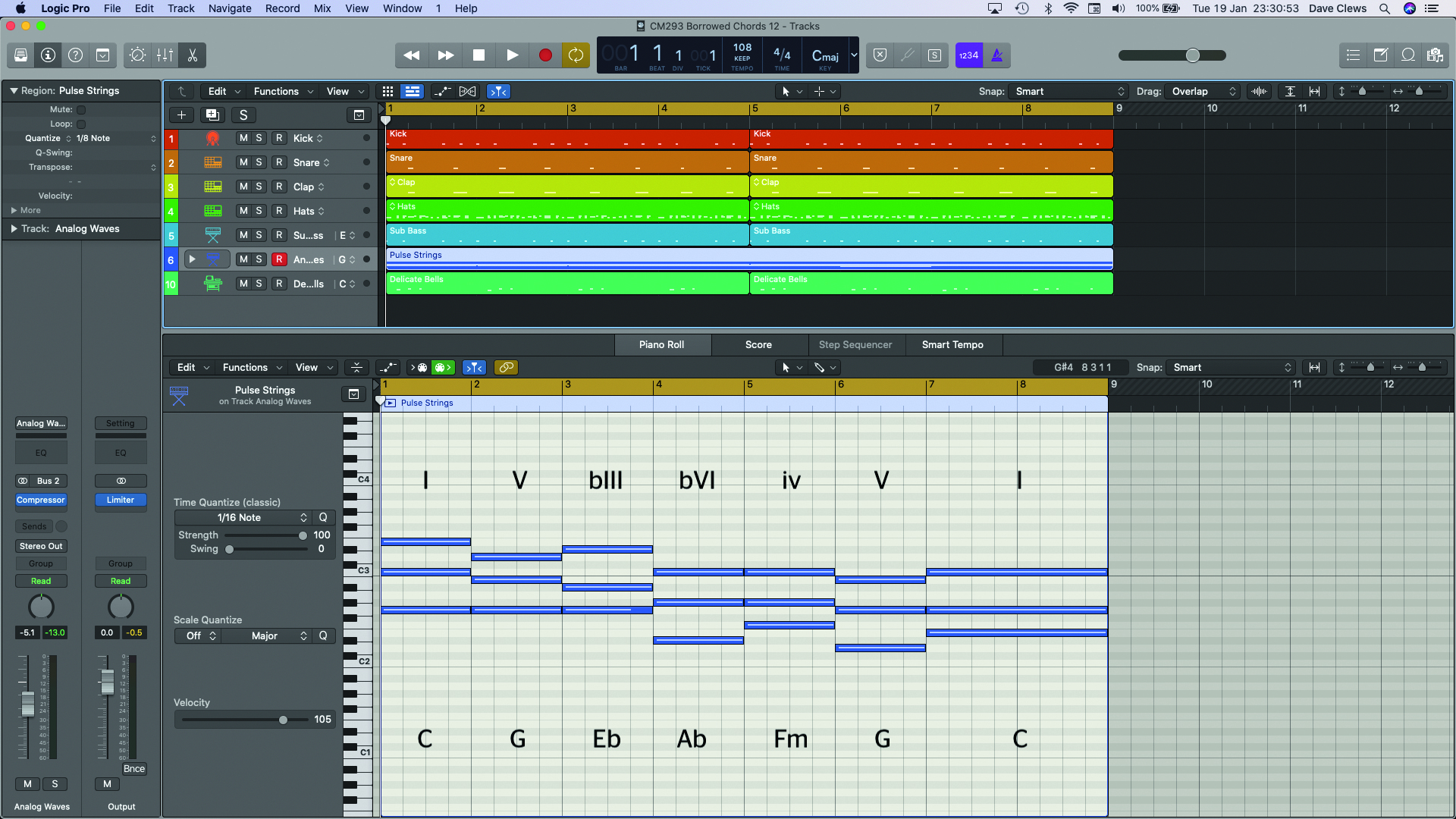

20. Use borrowed chords

Diatonic means ‘in key’, and diatonic chords are formed using only notes taken from a particular scale. So a C major scale containing the notes C-D-E-F-G-A and B – those are the white notes on a keyboard – would give you the following set of diatonic chords: C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am, and Bdim, formed by stacking alternate notes onto each note within the scale. These are the basic triads you may already be familiar with.

However, a palette of only seven chords can be limiting, so why not borrow chords from other keys? Borrowed chords are most often taken from parallel keys, which are keys that have the same root note as the original key. In the case of C major, the parallel minor key is C minor, so this gives us a whole new set of chords to choose from – Cm, Ddim, Eb, Fm, Gm, Ab and Bb.

21. Try pushing chords

There’s no doubt that any drums or percussion in your projects will do most to define the ‘rhythm’ of your tracks but the position of chords and even melodic notes will play a crucial role too. As such, if your chord parts only fall on the down-beats of each bar, you may well find that the overall sense of rhythm your track has is diluted or made predictable.

‘Pushing’ chords so that they fall a little early or late can make a big difference, by keeping your listeners on their toes. Even a push of 1/8th note either early or late can make a big difference.

22. Experiment with chord inversions

Inversions are, put simply, the idea of playing a chord with the notes in the ‘wrong order’, so instead of playing D major D-F#-A, you could play it A-D-F#, and still maintain the exact same feeling. One way to use inversions to good effect is to have the lowest notes match a bassline below.

23. Throw in passing notes

In our desire to make sure we hit the right notes in the right places, we often end up recording ‘block chords’ where the flow from one note to the next isn’t our first priority. That’s no problem, particularly if we go back to our recording and take a pair of scissors to it, chopping notes to create melodies and looking for ‘passing notes’, which help chords blend more sinuously from one to the next.

For example, cut holes into the top line of your chord progression and fill in the gaps between note steps, leave a note hanging over from one chord to the next, or add extra notes to enrich your harmony.

Artist tips

Opening up the blank canvas of your DAW can be an intimidating prospect for all of us, not just those at the beginning of their journey into music production.

The question of where exactly to start when you’re building a track is one that’s puzzled artists of all stripes, from bedroom beatmakers to hit producers, and each one has different methods for taking that first leap into the creative abyss.

We’ve spoken to more than a few accomplished music makers over the years, asking each artist how they typically embark on the creative process and get started on a track. Here’s what they had to say…

24. Tom VR

“I will often just pick a random project that I ditched months back and export it, drag it into a new project and manipulate it, then work on top of that. Almost like starting by messing around with a sample, but it’s my own discarded material. Recycling my old ideas and then building on top of them, that’s usually my process.”

25. Jas Shaw

“I tend to start with a ‘what if’ type idea, and usually it involves undoing something that was working and replacing it with something else that most likely doesn’t work yet. Then it’s a problem solving exercise that eventually results in a new working system. Secretly, the whole time I keep my ear out to see if it makes music for me. Once it’s working it’s not very interesting, so we start again.”

26. Sheep, Dog & Wolf

“Usually I’ll begin with a series of chords. Sometimes from piano, sometimes guitar, sometimes from vocal or saxophone improvisations. I’ll play those chords over and over and over, getting a loop going, then layer things up from there.”

27. Roosevelt

“That really depends on the idea, but it’s often based on a rhythm track. I’d record a drum beat and add a bassline on top. Drums and a bassline are often the fundament of a track for me, and I think you can hear that as the bass never plays just a functional role in my productions, it’s always adding a groove pattern.”

28. GOOSE

“It can be a melody you recorded on a phone, a drum loop, anything basically. After all those years we can say that we all have a couple of ways to approach a new track, but there is no formula – luckily! Making music is supposed to be done with magical, childlike enthusiasm; that’s why we do it. With every new song, I’m wondering where it came from.”

29. Model 86

“Up until recently I was starting with vocal samples but I’ve just changed my workflow. I’ve just sworn not to touch any samples at all if I can, just start on an instrument and vibe and manipulate stuff more organically and go from there.”

30. Coma

“Recently we’ve liked starting with an interesting-sounding instrument, which ends up putting a very unusual effect chain on a Rhodes, or download free animal sounds from a sample library and try to create an instrument with this on a sampler.”

31. Emptyset

“Often it’s much more interesting to develop a system for making music before you commit to making music. For example, you might limit yourself to recordings of playing your table percussively and then using extreme EQing. In trying to push a very limited sound palette as far as it will go you might discover a unique voice.”

32. Housemeister

“I’ll have days where I just program patterns and sounds. I might sit for a day just playing on the Analog Rytm programming beats. When one pattern is done, I don’t start a track, I just go to the next pattern and do it again – and so on. I’ll do that with all the machines, more or less.

“Then another day I’ll switch on the studio and a track is already there… by accident. I’ll find a nice hook made with a synth, then I already have loads of beats to choose from. It’s then a bit like a DJ set – all the instruments are the records which I mix.”

33. Ex Mykah

“When I start making a new track, I try to start with the story. This goes for classical music too. I feel like if I have a general idea of what kind of song I want to write, that really helps zero-in the production for the song. Otherwise it feels like I have way too many options.”

34. Suicideyear

“Usually when starting something new, it’s always melody that comes first. Most times I’ll come up with an arrangement and try a few different sounds/VSTs with it and decide where I want to go. I like to work on more melodies before going to drums, because, when I start making drums I get into a finish mode. Leaving the melodies open-ended/free of drums helps me build on it more.”

35. Pythius

“I try to start with writing a riff, since (at least for me) I noticed that putting drum patterns in early kinda dictates where the riff is going and that restricts creativity. Or I start with just messing about with a synth and build some sounds and sometimes that really helps with getting new ideas for melodies and riffs too.”

36. FVLCRVM

“Over the years it’s turned into recording ideas to my phone. Could be a sound, a hook or a drum beat. Sometimes I do it on the street, pretending I’m calling someone! But I guess it’s not common to beatbox to someone down the phone… So I act like I’m on a line to tech support and I wait for an answer while whistling. I know.

“I often take what is recorded and throw it straight into Live. The melody/beat-recognising algorithm is magical. And offbeat/off-scale stuff is sometimes really interesting.”

37. School of X

“In general I’ll have a melody recorded in my memos or I’ll start making a chord progression. Then I usually pick up a bass or drums. It can also be the other way around. I’ll have waves of recording lots of things and deleting. I try to kill my darlings. It’s important to tell yourself that there will be slow, less productive hours in creativity but it’s all part of getting where you wanna go.”

38. Jennifer Touch

“Mostly I start with a synth sequence from a single synth, I never play more than one, I just concentrate on that sound. This is the heart of the song or track. Usually a bass voice. Then I’ll add drums and try to get the vibe.

“Then I try vocals or another synthesiser or a guitar to wrap a melody around it. Usually the vocals are the last part of the meal. Once the basic notes are established, I go into individual parts for structuring, do the actual songwriting and put things in place.”

39. Selective Response

“Here’s something funny for you: I have no idea how I make the music I do. Like, I can tell you how I made it, but sometimes I listen back and think, ‘where did I even come up with that sound or idea?’. I enjoy pressing play and making things happen as I go. I have a rule that I must record a rough draft when jamming. Even if I don’t do anything with it, if I have a rough draft, I can either chuck it or have a foundation to work at.”

40. Becker & Mukai

“We normally hook up a load of hardware, often the Roland Juno-60, the TR-707 and TR-727… and with those create a bed for experimentation. We press record and let it roll for a long time, often 30 minutes, sometimes more, and create ideas from those long sessions. We’d include some random pieces of gear that happened to be around and try to push them to their limits.”

41. Niklas Paschburg

“I usually start on my piano and see if some melodies or harmonies inspire me. But it depends on the day and mood – whether I feel more into acoustic or electronic instruments. Sometimes I start with the OB6 and go later to the piano. I try to have every instrument ready to record so I can quickly jump to the synth or percussion instruments.”

42. Amirali

“It’s different each time, there’s no rulebook for me. Sometimes it starts with a melody or harmony, or it could simply be a bassline or a hook. There are also many times when I just press record and start jamming for half an hour, playing with the piano or a synth, then manipulating the sound and going crazy with it.”

43. Fahrland

“Everything I do in music is trial and error, watching others, thinking outside the box and staying true to your feelings. Sounds easy, but it’s an everyday challenge. Sometimes it’s difficult to find a musical detail worth making a song out of. It may be random jamming on new gear, or just the radio. It’s not always the ‘how’, but also the ‘why?’.”

44. Hypoxia

“For my Hypoxia material, those compositions begin with selecting one instrument from my collection, taking it out of the studio and isolating myself with that instrument, trying to create something compelling within that instrument’s limitations.”

45. Lapalux

“Thinking of music in a visual sense can really help break away from times where you feel uninspired. I like to try and write music to an image sometimes, moving or still. I find it really helps break away from stagnated ideas and the feeling that you’re stuck sometimes when creating music.

“Go to a gallery and research some artists that you find interesting, and try to recreate their work using sound. Likewise, watch a scene from a movie you love and try to build ideas and sounds that you think work with the visual in context.”

46. Visionist

“I like to gather a lot of sounds for a project and then work from them multiple times, this keeps a sonic consistency… Depending on what I want the track to represent determines whether I start with drums/sound design or melody, but the starting point is gathering and making sounds.”

47. Rural Tapes

“I enjoy using improvisation as a method for creating and composing. I can start with a drum beat, a weird sound, a drum machine, a series of chords, a simple melody or a field recording. Sometimes I can press record and tape for hours. Then I can pick out parts that I like and keep on layering them.

“There are no rules for the process of creating music in my world. I work very intuitively and usually I don’t have much planned before I start. Sometimes I end up using plain structures for a song and sometimes the lack of structures can be better.”

48. Project Pablo

“The flow varies from time to time, but I usually build a palette of sounds, then start with percussion and move from there. Sometimes I’ll just record as many different sounds as I can from some hardware, with no tempo or overall vision in mind, and save them in a folder to sample or rework at a later date.”

49. Jimmy Edgar

“It can start with an idea of any kind. A beat, a melody or chords. I like to play games with music when I am coming up with ideas for myself. My session last night was playing with chord progressions and reharmonisation using the Studio Electronics Omega 8. I wanted to see if I could make a song in which each bar is its own song and doesn’t repeat. I like to have fun and make my own parameters.”

50. BON

"I feel it’s like pottery, or woodcraft. I chisel away bit by bit, creating 4/8 bars at a time before moving on to the next and building on that. I like experimenting and exploring. I call it "letting the universe in", that delicate balance of curation vs creation. Sometimes you need to let go and see where it takes you."

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.