5 tracks producers need to hear by… Brian Eno

Best of 2021: In need of some inspiration? Draw yourself an oblique strategy card and treat your ears to the very best of the musician’s ‘non-musician’

Best of 2021: Rule-breaking, self-destructing, always there and yet never present… Working alongside Brian Eno has been compared to working alongside a gas. You might not feel his influence at the time but, when it hits, it’s a knockout.

He’s mysterious. He’s genius. He’s the self-described ‘non-musician’ who’s shaped million-sellers for David Bowie, U2, Coldplay, Talking Heads and more, earning himself a reputation as every burnt-out rock-god’s favourite muse in the process.

But, whether it’s through his stunning solo work or brave collaborations, in Eno world, nothing quite goes as you might expect. Meet the cat that hates to get in a box…

1. Roxy Music - Virginia Plain

It’s impossible to take a walk on planet Eno without snagging yourself repeatedly on the rosy thorns of Roxy Music’s Virginia Plain.

It’s a song without a chorus, instead serving up a laundry list of mad lyrics and honking stop/start experiments as recompense.

The title Virginia Plain refers to a painting (of a pack of cigarettes) Eno had recently completed and is barked out (by vocalist Bryan Ferry) only once before the song - completely spent - slams on the anchors at just 2:58 in length.

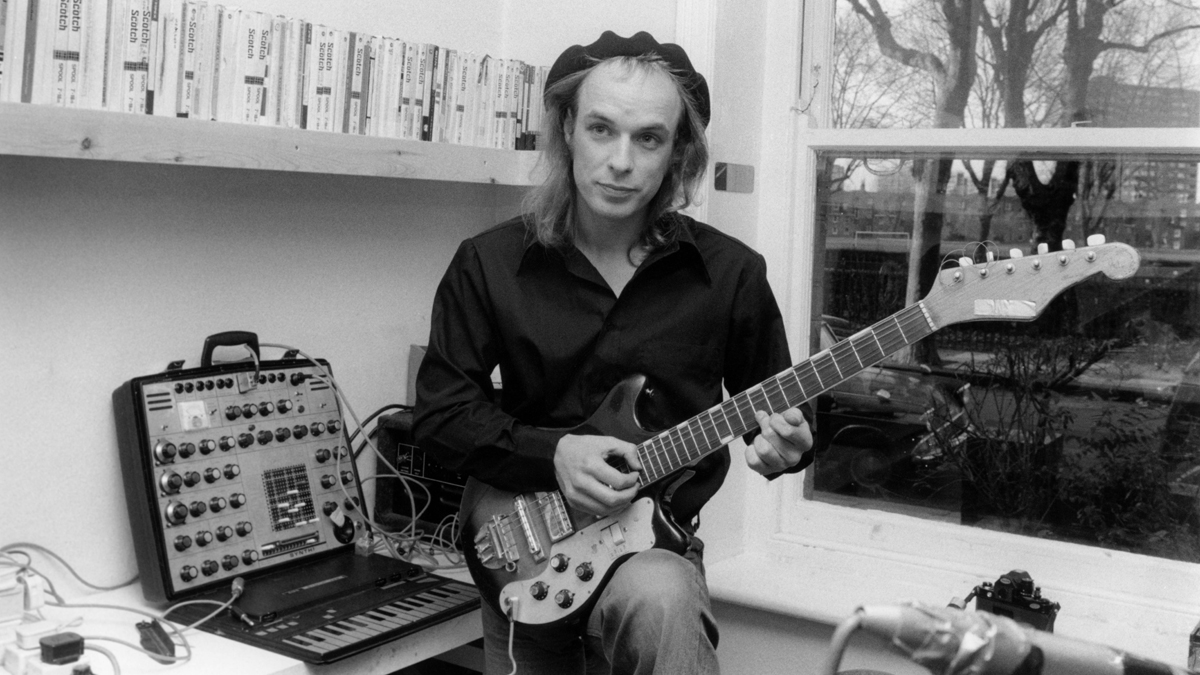

Let’s go back to 1972, when Virginia Plain was a production tour-de-force. Brave use of the stereo space, with rival instruments entirely dwelling hard left or right, serenade an ongoing procession of spot effects (including a motorcycle that kickstarts in the left ear and zooms over to the right) and repeated sprinklings of the only luggage that Eno always packed on a ‘trip’ - his trusty EMS Synthi AKS suitcase synth.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In his work with Roxy - while always a driving force behind the scenes for ever greater experimentation - it was his purposeful adjusting of the EMS (note: not keyboard playing) that was his raison d’detre. And while Eno’s costumes at the time were certainly enough to catch your eye - or even have it out - nerds and art-rockers alike instead marvelled past the sequins and that hair to gaze at the small white telephone exchange at Eno’s command…

The Synthi was a modular synth, but rather that take Moog’s route of multiple jack sockets and patch cables, it used a small pin matrix, allowing users to route sound and make connections internally by jamming small pins into tiny holes. As a result, it was much smaller and far trendier than the kind of Moog wardrobes being sported by less enlightened proggers.

The chic, diminutive Synthi came in two forms. The first, the Synthi A, available from May 1971, had a simple flat touch panel keyboard added almost as an afterthought, which folded flat against the main control body, allowing the user to carry it around via the handle on top, earning the machine the sub-moniker, ‘suitcase’.

Then, realising that someone might actually want to play the thing, an improved Synthi AKS came in 1972, adding a proper keyboard and even - remarkable for the time - a sequencer,so you could program notes rather than manually tap them out. Imagine…

We suggest you always enjoy Virginia Plain in proper stereo, but for the visual majesty of the band in de-rigeur ‘70s ‘all in a line, drummer at the FRONT’ formation, check out the fur-coated Eno brooding hard right in this legendary Top of the Pops clip and thrill to his spangly gloved entry at 2:13…

2. Brian Eno - Another Green World

It all starts here… Or rather it all stops here. 1975’s Another Green World marks Eno’s move away from more familiar Roxy art/rock indulgence in favour of the more experimental music that would come to define all of his subsequent work.

Eno’s first two albums weren’t actually that far from old Roxy, but Another Green World hangs up the furs, gets its remaining hair cut and gives cover credit to the newly mono-named ‘Eno’ instead.

The tracks are short. Interesting. Brilliantly and carefully recorded, and while sharp, pointy and arresting as previous work, there’s a new maturity and confidence at play above the urgency to impress.

Take, for example, the brilliant title track, best known as the ‘80s theme to TV arts show Arena. It sounds wonderful - it’s a brilliant piece of writing and sound sculpture - but Eno is happy to let a great tune pass us by as it drifts into consciousness then fades into absolutely nothing, and all within 1:45. If ever you hear complaints of Eno being overblown, failing to get to the point or - heaven forbid - boring, point the naysayer at Another Green World.

The ingenuity on board is at least in some part due to the discovery and refinement of Eno’s Oblique Strategies, steering Green World’s creation with Eno powerless to resist.

Oblique Strategies were a box of cards concocted in partnership with painter Peter Schmitt. The idea was that, when in need of a creative push or influence, one would simply draw a card and carry out the instruction upon it. The unsaid rule being that WHATEVER THE CARD SAID YOU HAD TO DO IT. And with cards reading ‘Destroy the most important thing’, and ‘Give way to your worst impulse’, drawing a card was not something to be taken lightly.

Fortunately, other cards included ‘Take a break’, ‘Is it finished?’ and ‘Do the washing up’, so it wasn’t all bad.

Eno’s own first set was hand-painted onto bamboo cards (natch) but - in favour of spreading their influence wider - versions were made printing the unquestionable advice onto conventional cards and placing them within a box.

Over the years there have been five slightly differing sets of the cards, with certain cards drifting out of favour with Eno - being replaced by new, more timely cards - only to then drift back into favour in later years. “Cards come and go,” explains Eno.

Similarly, the exact number of cards in a set differs. ‘Over 100’ claims the current listing with befitting haziness.

Looking for inspiration? Previously costly eBay trawls were required to snag a box, but right now you can buy your own set of (actual, genuine) Brian Eno Oblique Strategies at the Eno store. Yours for £40. Grab them before Eno changes them, adds a ‘Go Directly To Jail’ card or deletes them altogether. And read all about their intriguing history (and perhaps make your own sneaky set) via the descriptions here.

3. Brian Eno - 1/1

Taking a firm viewpoint on Eno’s ambient work involves balancing on a particularly arty fence. On one side the music is simplistic, meandering and aimless, with any possible deeper admiration for it instantly zapped by any knowledge of the random, machine-dependant way in which it was created. On the other… it sounds simply fantastic.

We’re all familiar with the old moans of ‘not real music’ and ‘made by machines’, and while these baseless accusations are frequently and foolishly levelled at anything that dares to use a synthesizer, in the case of Eno’s ambient works it’s an entirely fair finger to point.

Eno’s Ambients - our pick being Ambient 1: Music For Airports - are the products of long loops of tape of different lengths, each featuring slow-moving, evolving tones and melodies, that are left to run together, interacting differently at every pass and with the net output never repeating. Eno may have straight-faced the fact that one of the loops “repeats every 25 and 7/8ths of a second” in interviews, attempting to artfully analyse its deconstruction, but such stats are merely products where Eno made the cut and placed the sticky tape rather than any genius forward planning.

Worth saying that similar tape snippage on Airport’s superb predecessor Discreet Music does have a modicum of forethought involved, as the left channel (at 1 minute 3 seconds long) is almost exactly five seconds longer than the right channel (at 1 minute 8 seconds long). This means that the tracks drift five seconds further apart with every repeat and therefore - at roughly 15 minutes in - the two tracks step back into their original alignment. But genius? The (EMS Synthi suit) case remains open…

And yet there’s no denying that tracks such as Airport’s 1/1 and Discreet’s title track are enticing, daring listens that sound simply fabulous. So, like Jackson Pollack flinging paint at a canvas, who cares if Eno did little more than set up the gear and press go if a masterpiece is the result?

“Yeah, I could have done that,” you might argue. But you didn’t, did you? And you certainly didn’t do it in 1972.

4. Talking Heads - Once in a Lifetime

As with most bona fide classics, nailing origins and correctly portioning out credit starts out tricky then, as the track becomes recognised as one of the most important in musical history, becomes downright impossible. Suddenly, everybody claims a chunk of that impromptu jam turned global wonder…

So the story goes with Once In A Lifetime. Eno had been working with Talking Heads since 1978, producing their previous two albums before embarking on 1980’s Remain in Light. Keen to avoid repetition (including the merely mild commercial success of the previous albums) Eno exerted the influence of African rhythms on the band (the work of Fela Kuti being a favourite at the time) and encouraged ever lengthier jam sessions, after which the band would re-learn and replay their happy accidents as deliberate compositions.

Such a session created this tight, tuneless, shuffling jam, with very few musical elements other than Tina Weymouth’s famous pulsing bassline, made magnetic through David Byrne’s electrifying vocal.

Relief comes in the form of the chorus, the work of Eno, creating an odd writing credit, with ‘Initial Music’ credited to the band and Eno, and ‘Additional Music’ being the work of Byrne and Eno only.

The story goes that Eno disliked Weymouth’s now legendary bassline, thinking that the first note of the repeating riff was ‘too obvious’. So much so that he re-recorded it himself without the band or that introductory note present. However, Weymouth took exception and re-re-recorded her part with the note back in place… though in a nod to Eno, absent sporadically. Listen closely.

The song reached number 14 on the UK chart though, incredibly, only number 103 in the States. It did, however, go on to power Talking Heads’ famous Stop Making Sense live movie (home to Byrne’s equally famous big suit) and subsequently ’hit’ number 93 in live version form… Same as it ever was…

Oh, BTW: One track that narrowly missed our selection is Eno’s own excellent King’s Lead Hat, from his 1977 pre-Talking Heads album, Before and After Science. King’s Lead Hat being… wait a second… an anagram of… Talking Heads… Huh?…

5. U2 - The Unforgettable Fire

After their basic (but brilliant) War album, U2 went in search of their next level. They - of course - found it, and thus began a legacy that saw them move from lovable rough and ready proto-punks to global superstars to art/rock pranksters to their current ‘where next?’ hiatus (with a critical mauling as the stinkiest T-Rex in the graveyard of overblown rock dinosaurs somewhere in between).

It’s easy, therefore, to at least ‘tut’ at the mention of The Unforgettable Fire (and you’d be forgiven for cocking an even bigger snark at ‘Edge’s Hat’-era sequel The Joshua Tree) but it’s time to forgive the prattle and hum and dish credit where it’s due.

The Unforgettable Fire - the title track of the album - is - by a whisker - the neatest way to sum up what the band and Eno (with co-producer Daniel Lanois) achieved in 1984. For a band that could simply have put their foot back on the low-key gas and ground out another slab of practice-room rock, U2’s quest for a higher plain is at least commendable and - in the end - remarkable.

TUF is a successful, curious fusing of the punky drive they still had in spades, the soundscapey, airey, ambient BIGNESS that only an Eno can bring, and the rock ‘n’ roll folklore that - at this point - was yet to overpower and implode their music.

Yes, it’s a band playing their heart out. Yes, it’s all live, all real, but listen with a 2021 head on (rather than a 1984 one) and suddenly rather than ‘space’ and ‘gravitas’ you hear Lexicon reverb, the tinkling of the DX7 (alongside U2’s go-to Yamaha CP-80 electric grand) and - in the bridge - Fairlight Lo-Strings and Orch5 presets.

And, in hindsight, perhaps The Edge got too much credit for his genre-defining dub guitar work at the time. Take, for example, the syncopated repeats throughout the electric fan favourite Wire. Once you take on board that it was experimental, tape-loop-loving Eno at the controls, things sound rather different.

It’s easy to see how the new sound gained them broad American success, but less graspable (and more praiseworthy) is how their established fans came along for the journey, too. The Unforgettable Fire was HUGE internationally, reaching number 1 in the UK and other countries, and a balance-tipping 12 in the States.

Brian Eno: The widescreen collection

Say hello to more Eno. Take in the bigger picture and take FIVE MORE trips inside the expansive mind of the world’s most brilliant Brian via our extended selection of perfection.

1. Brian Eno - Deep Blue Day

Awash with pedal steel and synth tones in equal measure, this sumptuous, bluesy meandering truly washes over you in waves. Deep Blue Day, taken from 1983’s Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks - originally part of a lengthy art-flick/documentary setting old Apollo space mission footage to music - it’s simultaneously earthy and retro yet hauntingly space-age and alien.

We’ve already determined that if one instrument defined Eno’s sound it was the EMS Synthi AKS, but if there was a second love in Eno’s arsenal it would be Yamaha’s DX7. Introduced in 1983, the legendary DX7 was actually the third in Yamaha’s epoch-making all-digital FM synthesis ‘DX’ series, after the insanely expensive (only 140 made) DX1 and cut down (but still massive) dual-voiced DX5.

The DX series (including the DX7’s many more affordable spin-offs) changed the sound of synthesis, modulating layers of simple sine waves to create tones hitherto unheard and unimagined. A casual leaf through the two banks of 32 presets on board circa 1983 revealed stunning electric basses, impossible metallics, warm realistic brass and the classiest, glassiest electric pianos ever heard.

Problem was that, thanks to its non-intuitive, mind-blowing new paradigm of synthesis and a desire to keep the front panel as ‘80s un-knobular as possible (there are instead two rows of 16 flat buttons and a single ‘data entry’ slider), the DX7 was an impenetrable thing to program, meaning that very few users actually went beyond the 64 new sounds that came in the box.

Instead of liberating musicians to new levels of creativity, this UI face-palm instead froze modern music overnight, imposing the exact same bass, chimes, brass and pianos all over every hit record from 83 to 89.

That said, one user who did read the manual and get beyond simply stabbing ‘Electric Bass 1’ for the 57th time was - of course - Eno, who took to the DX7 like a duck to water, using it extensively across Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks.

“The reason why I enjoy the DX7 so much is because it teaches me so much about sound,” Eno told Keyboard magazine in 1987. “Samplers are fine and dandy, but not conceptually different from a tape recorder or a Mellotron. The DX7 on the other hand is a new way of generating sound.”

As part of the feature he even included four of his own favourite DX7 sounds relayed as tables of numbers requiring laborious data entry into the synth… But don’t worry. Here’s a download of those very same Eno presets in DX7 format .SYS file, compatible with your favourite DX clone plug-in and Korg’s Volca FM hardware.

2. Coldplay - Princess of China

Yup, we’re forgoing the extensively more Eno-heavy and dense Viva La Vida album (including the title track, which borrows the chords from Eno’s own An Ending (Ascent) from Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks) in favour of his parting shot with the band, the co-written fourth single from follow-up album Mylo Xyloto.

Xyloto is an altogether more electronic affair than the dusty, physical world of Vida, with a major production and writing squad of which Eno was just one element. However, it bears Eno’s experimental touches, with glitchy electronics, tribal, world-music beat and repeated glimmers of a sample of the opening moments of Sigur Rós’s ambient Takk clearly present at the start and throughout the song.

Mylo Xyloto represents the band’s fully blown moves for global takeover, building on the art-rock bedrock that Eno built for the band. Here the colours are a little brighter, the songs a little more pop and the backstory ‘concept album’ themes of the world of Silencia and the triumphs of music over its supremacist government a little more daft.

Mylo Xyloto is a ‘silencer’ tasked to hunt down the creative ‘sparkers’ under the command of Major Minus who sees the error of his ways and discovers the power of music and love… It’s like Paul McCartney’s Frog Chorus and Mike Batt’s Wombles never happened.

Either way, it fuelled the kind of world tour that a band only ever has to do once, and this hit single was written with Rihanna in mind, despite drummer Will Champion harbouring an intent to take on her vocal himself. Shame, as we’d have loved to have seen him take on Rihanna’s outfit in the video, too.

For all its prog/pop repositioning, concept confusion and critical naysaying, Princess of China broke new pop/rock boundaries for the band, reaching number 4 in the UK and a respectable 20 in the US while establishing the band as a global hot ticket for girls on shoulders everywhere.

3. Passengers - Original Soundtracks 1

Or - to call it by its proper name - U2’s weird album that they didn’t put their name to and which nobody bought.

Yes, it’s easy to get caught up in Eno’s reality distortion field and even U2 - after the success of The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree, ballsy comeback Achtung Baby and the coup of pulling off career reinvention Zooropa - finally stepped in the Eno do-do with this concept album without a concept…

The idea was that Eno and the band would jam while watching video clips and create soundtracks to films that didn’t exist… Stay with us here. Coming off the Zoo tour with nothing doing, the band found themselves cranking out 25 hours of experimentation.

In a sense, the result is a sequel to Eno’s own Music For Films album from 1978, but with the high-profile presence of Bono alongside ham-strung input from The Edge, Adam Clayton and - in particular - drummer Larry Mullen, it sounds like U2 with their balls on holiday.

Incredibly, the project was to capture some degree of zeitgeist upon release with first (and only) single Miss Sarajevo (featuring Luciano Pavarotti’s track-saving input from 2:41) reaching number 6 in the UK, but not getting a release in the US. The album went on to peak at 12 in the UK, but a less said the better 76 in the States.

And - despite that Original Soundtracks 1 title - we’re still awaiting Original Soundtracks 2…

4. The Microsoft Windows 95 start-up sound

Famously Microsoft paid The Rolling Stones $3m to use Start Me Up in its ads for Windows 95, its operating system revamp from that year. But did you also know that it employed none other than Eno to devise its six-second start-up tone?

His fee? $35,000. Nice work if you can get it. Had he been paid the same ‘per second’ rate for the 58+minutes of that 1995 Passengers album he’d have trousered $20.3million…

5. David Bowie - Heroes

Co-written by Eno and - of course - exemplary in album form on the album of the same name.

But let’s thrill to perhaps the best version of the track, Bowie’s live take from the 13 July 1985 Live Aid event. It can be argued that the global, stadium-rocking excess of Live Aid helped steer Bowie’s subsequent efforts into more pomp than circumstance (grinding to the career-derailing Never Let Me Down two years later) but it’s this heroic performance (with Thomas Dolby on synth) in front of 72,000 new fans and with the entire world watching that perhaps marks the height of Bowie’s power.

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too

“Turns out they weigh more than I thought... #tornthisway”: Mark Ronson injures himself trying to move a stage monitor