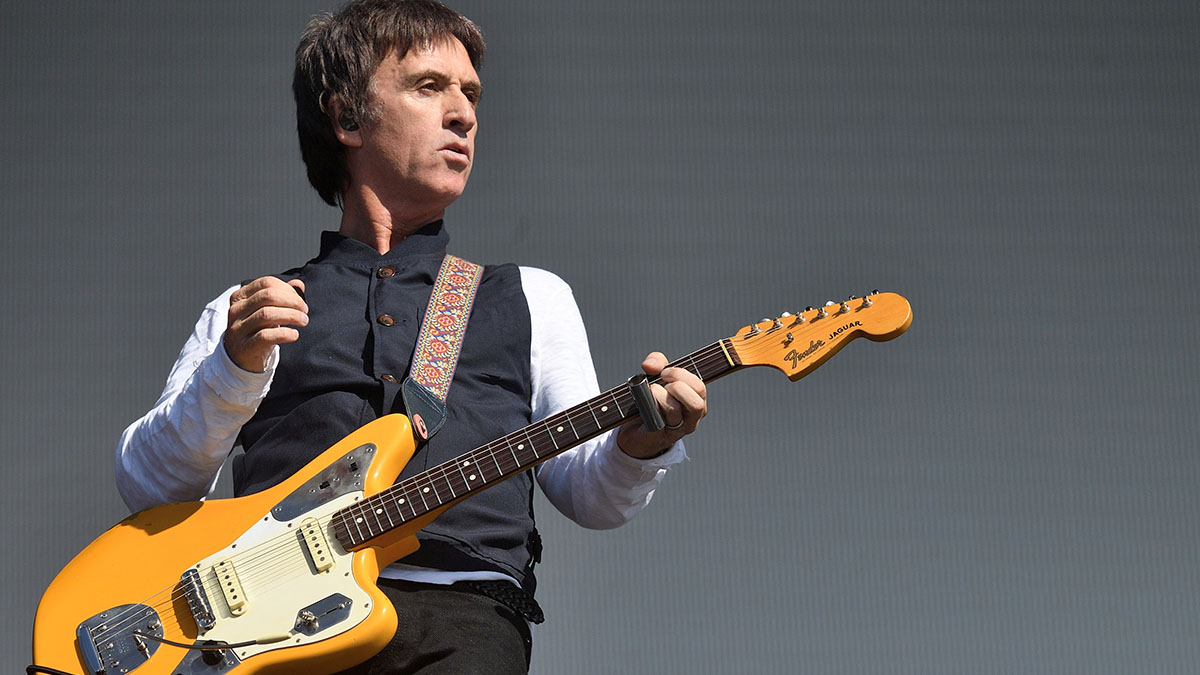

5 songs guitarists need to hear by... Johnny Marr

The former Smiths guitarist is a generational talent, the player Noel Gallagher calls the GOAT, but what songs should players check out to get a handle on his style?

There is no disputing that Johnny Marr is one of the greatest guitar players of his generation. The argument is whether he is the GOAT. Many people – Noel Gallagher included – would argue in the affirmative, and they would have ample evidence to back their claim up.

They could point to his discography with the Smiths, four albums that defined indie guitar in the first half of the ‘80s. It was as though Marr arrived on the scene fully formed. There was the kinetic spring of his electric guitar arpeggios. There was the naturally chorused jangle of 12-string guitar. There was acoustic guitar. There would be layers of guitars.

Marr would keep plenty in rotation; Rickenbackers, Telecasters, his trusty red Gibson Les Paul, an ES-335, and the Fender Jaguar – the offset electric he helped popularise.

Often, those guitars were capoed, perhaps at the second fret, pitching Marr’s guitar that bit higher and giving bassist Andy Rourke more room to manoeuvre and pick out the melodies and drive the song. The Smiths could be theatrical and playful; they could be brutal and to the point too. The Queen Is Dead retains its chastening drive and post-punk power all these years later, with Marr using the wah pedal as a filter over a righteous bassline from Rourke.

Marr was the perfect complement to Morrissey’s lyricism. The Smiths told stories rooted in everyday torments, in the humdrum of working class England; they saw the poetry in a grey sky, and it was just what a generation needed to hear.

After four studio albums it was over. The Smiths had split but Marr’s phone would not stop ringing. He would go on to play with Talking Heads, the Pretenders, Modest Mouse, the Cribs, dropping in every now and again for a cameo with Gallagher on High Flying Birds material.

Pretty Boy, off High Flying Birds’ latest studio album, Council Skies, features Marr on guitar. As Gallagher recently recounted to the NME, he didn’t need to send Marr the track in advance. Marr just turned up, plugged his Fender Jaguar in and worked on it there and then.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“He doesn’t get you to send him the track, he turns up, plugs his gear in, puts his guitar on, stands in front of the speakers and says, ‘Right, let’s hear it’. As he’s hearing it for the first time, he plays it,” said Gallagher. “I wouldn’t tell him what to play, I wouldn’t be so cheeky.”

Some of Marr’s best work was done in the company of Matt Johnson in The The – another of England’s great poets of the downbeat. It was a surprise that it would take until 2013 that he would launch his debut solo album, The Messenger, but if people keep calling you up and getting you to play, where do you find the time?

Recent years have seen Marr joining Hans Zimmer’s roster of musicians, collaborating with the composer on soundtracks to Christopher Nolan’s Inception and the latest Bond movie, No Time To Die – projects in which he has explored the electric 12-string in search of sounds out of reach of synthesizer and orchestral manoeuvres. Check out the live performance of Time to see how this sounds in practice.

Johnny Marr looks back on Electronic's debut album 30 years on: "I was living in a cultural revolution, at the real centre of it, and I was escaping a very negative scenario"

There are any number of places you could take any conversation about Marr’s greatest guitar tracks, any number of places that conversation could end. Some of his Marr’s most interesting work was outside of what would be conventionally be described as guitar music.

Teaming up with New Order’s Bernard Sumner in Electronic would play to Marr’s strengths with melody, as well as bringing us the collector’s item of an acoustic solo in Getting Away With It that is more Majorca than Manchester – a moment of Balearic levity at a time when dance culture became as habitualised to the Great British weekend routine as association football.

Forbidden City, from Electronic’s second album, Raise The Pressure, is another from the Marr/Sumner collaboration that reveals more of his style, the jangle pop abutting the avant garde when Marr takes another solo, only this time far more unconventional, blurring the line between guitar and synth.

“I wanted the guitar solo to be like a pop-art painting but still melodic,” said Marr. “That was me sampling a load of notes I was playing through Marshalls, and then playing it with a MIDI guitar so it still felt like I was playing with a guitar, but through a keyboard, and then with a Doppler effect on it. You can go to that extreme.”

At the other extreme, you can play to the guitar’s strengths and keep as many open notes in the chord voicings as possible, as Marr does on tracks like Hand In Glove. As the sole guitar player, there was a lot of sound to cover in The Smiths, spaces that could accommodate multi-tracked guitars and different textures.

His sensibility for layered guitars long predated The Smiths. As soon as Marr got his first drum machine and started writing, he would experiment with multi-layered guitars. He had a picture in his head how a recording might go.

“This was pre-Smiths, and I would often be like, ‘Does it sound like a record?’” he said. “I am not talking about technical things about compression. I’m talking about, ‘If I wanted to put 10 guitars on there I would have to make it sound like four or five.’”

Some players just live for the stage and look at the studio as a means to an end but Marr has always been fascinated by and enjoyed that process of creating something in the room with the band, leaning on the producer and engineer’s expertise.

“I did that with a lot of guitars stuff on The Smiths with John Porter at three o’clock in the morning,” he said. “I’m hitting the chord as he’s hitting the tremolo pedal. ‘Oh no, do it again – it’s not quite in time.’ Whereas now, you’d just move a mouse. There is a lot of fun in the physical art of making records and I am still very enthusiastic about that.”

That could make things difficult for him when trying to recreate the sound live. His logic, however, was sound. There is no good reason to sell the record short even if you’re going to box clever when performing it before an audience. On such occasions, Marr would play the song as he wrote it. If a studio overdub or effect had become such a feature in the track, he would play the overdub.

Marr’s influences are all over the map. There are the foundational rock ’n’ roll touchstones, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. There was glam rock, T.Rex et al. Folk was huge, too; Pentangle, Bert Jansch, Richard Thompson. Neil Young. Marr and Rourke became pals at school in part because they both likes Young. The players he grew up with in a working-class neighbourhood in Manchester were a source of inspiration, too. They would turn him on to new sounds, and those sounds would invariably make their way onto Marr’s records.

The five songs we have highlighted here are not selected as a Top Five but as examples of Marr’s playing style and the kinds of sounds he has been in thrall too since he started making records. There are the unorthodox chord voicings, guitars shifted into different keys via a capo.

Some are noteworthy for the studio engineering, others for Marr’s manual dexterity, his ability to play rhythm and lead as one, to carry the melody and the song while also giving us something interesting to listen to – and then ultimately to wonder just exactly just how he did it.

This Charming Man

This Charming Man is built upon Marr’s reluctant virtuosity and the Smiths’ ability to identify and articulate the profound agonies in the humdrum mundanity of everyday life. Here Marr has the inspired audacity to spritz up our dull existence with a guitar motif informed by Ghanian highlife guitar.

Within one song we get an idea of how widescreen the Smiths sound was; the jangle from the late James Honeyman-Scott of the Pretenders; a melodic spritz that could be from an E.T. Mensah record, or from the legendary Nigerian guitarist Victor Uwaifo. That we are hearing this track and thinking highlife, or calypso, still seems daring for early ‘80s Manchester, England.

The version that was recorded for the John Peel’s BBC Radio 1 sessions that later appeared on 1984 compilation Hatful Of Hollow sounds more like a work in progress. The version that turned up on the US version of The Smiths’ debut gives Marr’s solo more room to work the floor and open up the track to all kinds of musical possibilities.

Guitar-wise, this had everything, but never to the exclusion of everything else. As ever on a Smith’s track, Rourke’s bass still carries so much of the melody and musical information, and the upbeat major key guitar that’s front and centre only makes sense in the logic of the the band’s unorthodox songwriting. Speaking to Guitar Player in 1990, Marr put the number of guitar tracks on the recording at “about 15”.

“People thought the main part was a Rickenbacker, but it was really a ’54 Tele,” he said. “There are three tracks of acoustic guitar, a backwards guitar with a really long reverb, and the effect of dropping knives on the guitar. That comes in at the end of the chorus.”

Dropping knives on the guitar? That’s another lesson we can take from a player like Marr, to use whatever we have at our disposal to find new sounds.

Check out (Nothing But) Flowers by Talking Heads for another example of Marr’s highlife-inspired playing.

“I’m not an avid follower of African music, but I’ve heard plenty of stuff that I really like,” Marr told Guitar Player. “I’m interested in how highlife and I come together, because unintentionally, I’m a very highlife player. I guess I like overstated melody.”

How Soon Is Now?

Marr threw everything at How Soon Is Now?, and in producer John Porter he had an able and willing accomplice to help create the most dramatic tremolo sound ever committed to tape. “Right from the off on a record I always thought the guitar should make its presence known in the first three seconds,” said Marr. He got that here and then some here.

The hypnotic pulse of the intro is one of the sounds every player wants to recreate at home, just to see if it is possible, only to finish the day staring at the tremolo pedal in disappointment. We can find workarounds, setting two tremolos at different speeds. We can get close. But what is coming through the speaker here is more than just a stereo tremolo effect.

This was studio voodoo, taking a leaf out of the Beatles’ book to use the environment as a laboratory, as an instrument itself. They would track a rhythm guitar through a Roland Jazz Chorus, one through a DI. The DI signal would be sent to a series of Fender Twin combos – three or four, the recollections differ – with the vibrato effect engaged at different speeds for a triplet feel. The sound, panned left and right, paints the song in e dimensions.

There are other tone tricks that add depth and movement, such as a Leslie guitar. Porter asked Marr just to play through the song and jam to it, and then would take those pieces of guitar and feed them into an AMS DMX 15-80 stereo digital delay. Then there is the slide guitar. Speaking to Guitar World in 2020, Porter likened the slide part to a backing vocal.

“The song was all on the I but it had these ‘III IV’ chord changes every eight bars or so,” said Porter. “Morrissey would never allow backing vocals on Smiths records – I think only one time, maybe, with Kirsty [MacColl on Ask] –and I thought it was missing out this huge area.

“I started thinking, well, if The Beatles had done this, they would have done some ‘oohs’ and ‘aahs’ or something at that point in the song, so I would get Johnny to do a guitar part that would be the equivalent of having a backing vocalist.

And yet for all the clever sound engineering, this is a track that moves to a simple groove inspired by Bo Diddley, by way of Hamilton Bohannon’s Disco Stomp single that caught Marr’s ear. Without that groove, all that sound is just ambience. The rhythm is king.

The Headmaster’s Ritual

The Headmaster’s Ritual is in open E (tuned E-B-E-G#-B-E) tuning and is a masterclass in seeking out chords from off the beaten path and then presenting them in a song that stirs with an urgent, fidgety countercultural energy.

This competing tension between dreamy psychedelic sounds and straightforward pop melodies are a leitmotif in Marr’s playing. “I love pop but it is not enough for me,” he said. “I never want it to be too straight.”

The song itself is about corporal punishment in the British school system and what is learning barre chords if not a form of self-imposed corporal punishment? Well, experimentation with open tunings can be a good way of building strength in the index finger for the inexperienced.

They are also similarly helpful for breaking out of a rut. They can rewire our playing and force us to look at the fretboard differently. Marr admits he chose the tuning for that reason.

“I think it is a handy device for cutting out the brain static that gets in the way of chord changes,” said Marr, teaching the track on a Fender Artist Check-In series.

Open tunings also play right into his signature style, allowing his arpeggios to ring out, to find common tonalities and that thread the chord changes together, all of which goes a long way towards support the melody.

But the funny thing is Marr takes those precautions against automatic chord changes and yet his choices are classically his, finding himself at the eight fret for a Cadd9, and enjoying that sound, he moves the same shape up and down the neck – a similar principle as playing a riff on power chords but with a very different result. Marr then resolves this with a signature riff worked around a couple of arpeggios.

While the song is performed in open E, Marr told Guitar Player that he wrote it in open D and used a capo at the 2nd fret – Joni Mitchell meets the MC5 was the vibe, with some George Harrison in there too – and we are hearing a Martin D-28 with two tracks of Rickenbacker. The high-end sheen at the end of the track comes courtesy of an Epiphone Coronet strung with high-strings from a set of 12-strings.

Bigmouth Strikes Again

The Queen Is Dead is front-to-back essential listening, opening with the propulsive post-punk of the title track, with Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others closing things out with a brisk tour-de-force of eighth note arpeggios. It also features the band’s finest hour, There Is A Light That Never Goes out.

From a guitar perspective, the track that opens Side B – described by Marr as his Jumpin’ Jack Flash – is definitely worthy of study and the one we’re choosing. It’s a lesson in how acoustic guitar can be used as a steamroller.

Heavy strummed on six and 12-string acoustics with a capo at the fourth fret, it is a tidal wave of C#minor open chords. There is something in the Jumpin’ Jack Flash comparison; this, too, is all forward motion. And yet the energy is very different.

The relentlessness in the rhythm guitar calls to mind the Wall of Sound production of Phil Spector, and the girl group sounds that would be percolating among Marr’s many different influences. All those strings give it a papery brittleness. The chord progression – minor to min7, add11, add9/11, minor, major, maj7 – sketches out the melody where typically we might have expected Marr to add another guitar track to make it more explicit.

Staccato lead breaks on electric break things up. Once more the AMS DMX 15-80 unit is doing some work. Marr told Guitar Player in 1990 that he is playing slide through the AMS, “really high”, while the second break his is Les Paul Black Beauty mixed with his Rickenbacker that he samples and triggers off a roll of the snare drum.

There are more ornate, more decorated, busier compositions in his catalogue but Bigmouth Strikes Again shows what Marr can do when he seems under the spell of one simple yet overwhelmingly convincing idea. Upstarts, the first single from his debut solo album, The Messenger, has a completely different vibe but feels like it could be one of those tracks that came together in service of one idea or mood, in the latter case T.Rex and the glam-rock scene that helped give Marr the guitar bug in the first place.

Slow Emotion Replay

Marr’s brief in The The was to explicitly seek out new sounds and go off the deep end, and that he did. Marr did a lot of great work on The The’s 1989 album Mind Bomb, and just as on How Soon Is Now?, inspiration often arrived in the wee small hours.

Good Morning Beautiful was another of his 3AM epiphanies, playing a ’59 Les Paul with a wah pedal and a pair of Fender Twins for the biggest tone possible. Mind Bomb’s Beyond Love is a good example of Marr’s sound with a Strat, working the volume knob and using a TC Electronic 2290 rackmounted delay unit.

One of the coolest tones he got with The The comes on The Violence Of Truth, and it’s notable because for all the weird tones he has engineered over the years, he has tended to stay clear of overdrive and distortion. On The Violence Of Truth, however, he ran his Les Paul into the desk and ran the inputs hot for “almost hi-fi distortion”.

But The The’s follow-up to Mind Bomb took Marr and Johnson’s collaboration deeper. It’s a darker album. Johnson was going through a tough time after the death of his brother Eugene in 1989. Just listen to Dogs Of Lust, with Marr’s harmonica hyperventilating over a relaxed swampy guitar groove.

Helpline Operator finds Marr working a louche riff with a wah, accenting the beat on the toe down. But Slow Emotion Replay is the standout for guitar players – for the chord changes and the sparkling arpeggios alone.

The harmonica traces out the melody. Slow Emotion Replay should have been a hit. It should have been massive. It is almost like listening to the Smiths through the looking glass; again, Marr with a poetic lyricist, allowing those chords to tumble out under the verse.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

“Every note counts and fits perfectly”: Kirk Hammett names his best Metallica solo – and no, it’s not One or Master Of Puppets

“I can write anything... Just tell me what you want. You want death metal in C? Okay, here it is. A little country and western? Reggae, blues, whatever”: Yngwie Malmsteen on classical epiphanies, modern art and why he embraces the cliff edge