5 songs guitarists need to hear by… The Doors

Robby Krieger’s quicksilver style helped the LA quartet marshal jazz, blues, flamenco and more under rock’s acid glare

The Doors were the original fusion band. Whatever fusion is, whatever it means, surely the descriptor applies to the Los Angeles quartet – a band who folded jazz, classical, psych, flamenco, blues and funk into a singular rock ’n’ roll sound.

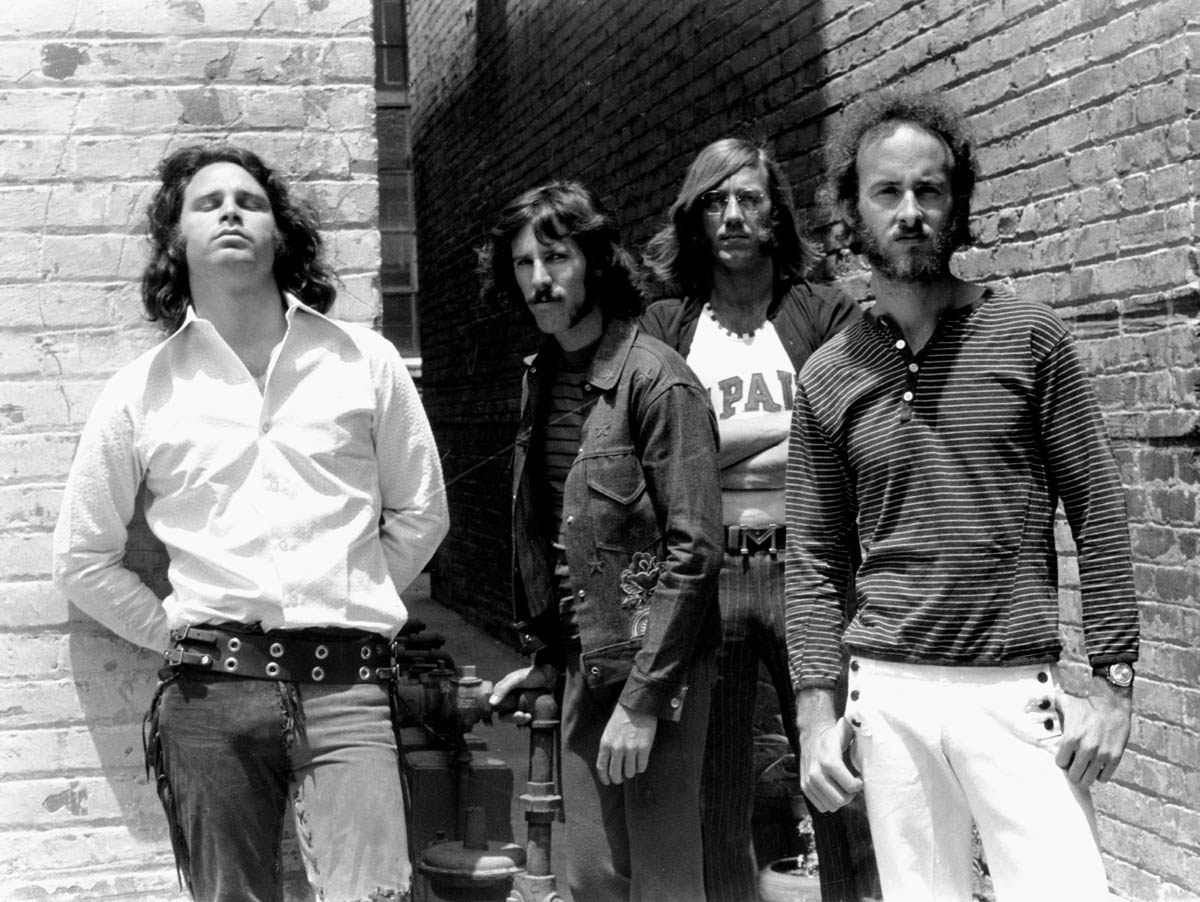

Formed in 1965, a febrile period for popular culture, The Doors were a freak occurrence that could have only happened in the 60s. You had John Densmore on drums, Ray Manzarek on keys and organ, Robby Krieger alternating between electric guitar and classical.

All three players were formally introduced at a meditation group, as each sought an alternative to to LSD as a means of mind-expansion. They were joined by Jim Morrison on vocals, the vinyl-trousered Lizard King, a totemic frontman whose charisma masked a self-destructive impulse.

If rock ’n’ roll anchored their sound, it was pulled in all different directions, chief among them jazz. Densmore was in his high school jazz band, and he and Krieger would frequent jazz clubs and immerse themselves in it. Krieger’s background was in flamenco and classical guitar.

This allied to a blues sensibility and a proficiency for slide kept his style moving on record, weaving in and out as Manzarek’s offered a melodic counterpoint with his Vox Continental and a Fender Rhodes Piano Bass.

Krieger favoured a Gibson SG Special going into a Fender Twin Reverb, occasionally using a Gibson FZ-1 Maestro fuzz box, and definitely making use of the echo room at Sunset Sound where, under the watchful eye of producer Paul A Rothchild, The Doors began their recording career.

From the beginning, The Doors had an iconoclastic impulse. Perhaps it was not so much the styles that they drew from but the spirit with which they used them that was key. Above all, there had to be dynamics.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Krieger and Manzarek will often withdraw from a composition, letting Densmore keep the beat going, or Morrison cut loose on the mic, and then they’ll dial it up. There are moments of pop psychedelia, moments of noise-rock, blue-collar boogie and beat poetry.

Where do you start with The Doors? Perhaps it is best to start from the beginning, and go on the journey with them. L.A. Woman might be their most complete album. With Morrison’s lifestyle catching up with him, there was an effort to pare their sound back to its essence. Defining that essence, however, is easier said than done.

After all, The Doors' sound was kaleidoscopic. Just look at their biggest hit, the first pick on our list, a song that is an obvious choice, sure, but one that brings Bach and Coltrane together and somehow makes it work. Such stylistic choices could only have been made by The Doors, because only they could write and perform them. Besides, no one else would dare.

1. Light My Fire – (The Doors, 1967)

The Doors’ most famous track is a propulsive work of excess, of psychedelic lounge jazz and casual virtuosity. And when you strip it down to its raw materials, it was a most unlikely hit. Light My Fire finds the LA quartet at their most formally audacious, with Manzarek’s gaudy keys a celebratory Roman candle of Bach-inspired melody, ushering in a complex arrangement in which Krieger uses as many chords as he could.

“When I wrote that, I said to myself, ‘Okay, I’m going to put every chord I know into this song!” he told Total Guitar in 2020. “I think there’s seven chords just in that intro. G to D to F to Bb, Eb, Ab, A. People don’t realise how many chords are in that song.”

Inspired by John Coltrane’s My Favorite Things, the middle section finds The Doors hit their stride as a jam band par excellence.

When I wrote that, I said to myself, ‘Okay, I’m going to put every chord I know into this song!‘

Robby Krieger

As ever, John Densmore’s sumptuous touch keeps the performance light on its feet as Krieger and Manzarek vamp over the top. Krieger’s phrasing has the raw instinctive whimsy of free jazz, but as in the rest of The Doors canon, he never overplays.

Leaving space in the mix was a crucial part of The Doors’ sound. Jim Morrison was a quasi-mythical figure, a shamanic lightning rod for the audience’s (and the authorities’) attentions, but he, too, knew when to step aside and let the light and shade of dynamics work their sweet magic, proving that even in the spiralling dysfunction of the late 60s, a little discipline and patience goes a long way when constructing a sound.

2. Spanish Caravan – (Waiting For The Sun, 1968)

Another triumph of stylistic abandon, Spanish Caravan sees Krieger lean on his classical and flamenco training, reworking the great Spanish composer and pianist Isaac Albéniz’s Asturias on what would be another vehicle for Morrison’s countercultural mysticism.

Opening with a flurry of fingerstyle nylon guitar, Spanish Caravan is given depth and weight as Manzarek chimes in, the leyenda form giving what might have been a whimsical piece a sense of the profound. The rubato feel of the intro shifts the ground beneath your feet, removing any expectations of where the piece is going next.

In an era when everyone was a seeker, Spanish Caravan offered rock ’n’ roll a new horizon. It extended its possibilities. Krieger’s use of a fuzz pedal here, most likely a FZ-1 Maestro, prefigures metal’s appropriation of classical melody – just the sort of thing that Ritchie Blackmore and Iron Maiden would do in later years.

Waiting For The Sun has some of Krieger’s finest moments. Besides Spanish Caravan, Yes, The River Knows has some breathtaking interplay with Manzarek, and Kreiger reworked it for his latest solo album, The Ritual Begins At Sundown, his slide guitar assuming the role of Jim Morrison’s vocal line.

By this point, perhaps Krieger was enjoying more freedom. Douglas Lubahn was guesting on electric bass, and was joined on Spanish Caravan by jazz bassist Leroy Vinnegar, who played acoustic. Nineteen-sixty-eight proved was a year of contrasts for The Doors. Amid their cresting popularity, storm clouds gathered overhead.

There was the controversy over Hello, I Love You and its similarity to The Kinks’ All Day and All of the Night, Morrison’s drinking was a growing concern, while the combustible atmosphere surrounding their live shows promised disorder somewhere down the line...

3. Roadhouse Blues – (Morrison Hotel, 1970)

For straight-up blues jam on which The Doors are their most accessible, Roadhouse Blues is a work of alchemy. Consider this: it has been covered to death, most notably by Status Quo and Blue Öyster Cult, is on regular rotation on jukeboxes the world over, and at heart it is but a simple boogie-woogie shuffle, and yet somehow its magic remains undiminished five decades on.

For all the cover versions, for all that this is Krieger at his most conventional – with his phrasing favouring pentatonic triplets on what was an improvised solo – there is a quality to the production and performances that convinces you that you are hearing it for the first time. And that is exhilarating.

Much credit for this must go to a rhythm section that included Lonnie Mack sitting in on bass after Ray Neapolitan couldn’t get to the studio in time, and, of course, Jim Morrison, who is at his ursine best here – an end times master of ceremonies with a throat loosened by whiskey.

But when all is said and done, Krieger’s blues playing here is exceptional. For further examples, see Crawling King Snake (L.A. Woman, 1971), Five To One (Waiting For The Sun, 1968). Krieger always lands on the groove, finding the sweet spot to best complement Manzarek.

Roadhouse Blues? There is a difference between being able to play Roadhouse Blues – which Krieger helpfully shows us in the video below – and being able to, y’know, really play it.

4. Moonlight Drive (Strange Days, 1967)

Moonlight Drive is a blues jam for acid freaks. On a page of score, it might do a decent job of appearing as blues, but there’s something off about Krieger’s slide playing, and what we mean by off is that his phrasing and note choice are Dali-esque, playful and surreal.

If slide playing has forever served the guitarist as shorthand for the human voice, here it is as through Krieger is referencing the animal kingdom on a lysergic, hypnotic groove.

Moonlight Drive features one of Krieger’s most flamboyant solos, the softly-spoken guitarist cutting loose on a blues I-IV-V progression laced with the cuckoo clock squawk from the verse. Genius, and to think this was a B-side…

As with Wild Child (The Soft Parade, 1970), Moonlight Drive is performed in open G tuning. Krieger tracked it on his 1954 Gibson Les Paul Custom, which would be his go-to guitar for slide, and most likely this would have gone into a Fender Twin Reverb.

Lyrically, Moonlight Drive was one of many songs written by Morrison on the roof of his house on Venice Beach. As Krieger remembers it, this was the good old days, when Morrison was on the weed and the acid, before the hooch darkened his outlook.

This was a banner year for acid freaks. You had Strange Days, Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow, Pink Floyd’s debut, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn. No two sounded alike, but a similarly mind-expanding spirit guided them. Far out. Moonlight Drive is one of The Doors most-fun trips.

5. The End – (The Doors, 1967)

The End was a breakup song of Morrison’s that was fleshed out in the moment onstage and would go on to become one of The Doors’ most notorious tracks.

This was the song in which Morrison’s Oedipal poetry lost them their regular gig at the Whisky a Go Go. Its profanity spooked the suits. Morrison went where no one had gone before in verse and it set the tone for The Doors’ countercultural resumé.

The End is crucial to understanding The Doors, Morrison’s fundamental preoccupations with sex and death, with creation and destruction, and opening up the rock song to the promise of performance art. What else is a jam if not performance art?

One of their many apocalyptic tracks, The End feels like a spiritual precursor to the sour darkness that would course through their heaviest jams, L’America, Five To One and Not To Touch The Earth

The Doors were masters of walking the line between abstract chaos and the discipline of a rock ’n’ roll composition. One of their many apocalyptic tracks, The End feels like a spiritual precursor to the sour darkness that would course through their heaviest jams, L’America (L.A. Woman, 1971), Five To One and Not To Touch The Earth (Waiting For The Sun, 1968).

Much of it sounds improvised, and no two live versions sound the same. Their 1970 Isle Of Wight Festival performance could be definitive, but the old caveat applies, ‘You had to be there, man.’

Krieger’s guitar comes and goes, ascending and descending through Arabic scales, chromatics, free jazz as psychedelia, atonal noise and skronk, and yet there is a regular motif that grounds the song. What was being heard through the control room in Sunset Sound was in tune with what was going on across town at TTG Studios as The Velvet Underground tracked Heroin, both stretched the rock song into the realm of the doomed epic.

Musically, structurally, it is fascinating. Whether you are listening to the studio edit on a Best Of…, journeying through the heart of darkness as Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now unspools, or you immersive yourself in the 1968 live footage from the Hollywood Bowl, its narrative structure remains provocative and daring.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

“It is ingrained with my artwork, an art piece that I had done years ago called Sunburst”: Serj Tankian and the Gibson Custom Shop team up for limited edition signature Foundations Les Paul Modern

“The last thing Billy and I wanted to do was retread and say, ‘Hey, let’s do another Rebel Yell.’ We’ve already done that”: Guitar hero Steve Stevens lifts the lid on the new Billy Idol album