Celebrating the hardware and heroes that built techno

We delve back through decades' worth of interviews to discover how the changing face of technology has shaped the sound of techno

SYNTH WEEK 2022: The dawn of techno – and the first true techno record – isn't easy to define but it's safe to say that 40 years ago electronic music began to splinter in interesting new ways with pop and dance, while both using the new synth, sequencer and drum machine tech, began to use it in dramatically different ways.

1982 Ten Ragas To A Disco Beat by Charanjit Singh is often held up to be the birth of acid and techno (being a 'modern' update of traditional indian folk music that bent the synths of the time in a direction they'd never previously pursued). But to pin that tag on this one curio as the kickstarter to a whole musical revolution? Unlikely…

Instead it's far more sensible to highlight the early 80s roots of synth pop and electro, with techno arriving as byproduct of the arrival of the first wave of truly affordable electronic instruments reaching wannabe music-makers and DJs, packed with bold new ideas and without any kind of desire to use the gear in the way in which its makers intended.

Even if the precise date is up in the air, you can certainly tie the birth of techno to a place - the city of Detroit - and a small circle of young Black musicians.

If there is a single originator, it would be Juan Atkins. As a young man at the dawn of the 1980s, Atkins acquired his first synths - first a Korg MS-10, then later a Sequential Pro One - and began experimenting with creating tracks, resulting in a string of proto-techno releases under the moniker Cybotron with friend Rik Davis.

While quite simplistic in their construction, the earliest Cybrotron releases, such as 1981’s Alleys Of Your Mind, bear a distinct similarity to European synth acts such as Kraftwerk and Gary Numan, whose hit Cars had arrived two years previously.

Atkins, along with close friends and fellow techno pioneers Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May, would absorb an eclectic melting pot of musical styles through Detroit’s legendary local radio stations and influential hosts such as WGPR-FM’s Electrifying Mojo.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The trio - informally dubbed the Belleville Three, after the suburb of Detroit they called home – have cited everyone from homegrown Motown icons to David Bowie, New Order, Parliament and even the B-52s as early influences. Despite the shared listening experiences, techno’s founders came from different places as musicians.

“I’ve been making music all my life, starting out with a guitar, then a drum set, but I didn’t really start experimenting with electronics until around 1978,” Atkins explained to Future Music in 1999 (FM80). “I hadn’t heard of people like Kraftwerk at that time, but I’d been working on demos, really early versions of tracks like Alleys Of Your Mind that were put together on cassette.

“At that time I had a basic mixer and a Korg MS-10, which was the synth that really developed my interest, introducing me to waveforms and oscillators. I’d just bounce between two cassette decks, taping from one to the other to create the overdub. There’s a real art to that.”

"I’d just bounce between two cassette decks, taping from one to the other to create the overdub. There’s a real art to that.”

Juan Atkins

For Atkins, an element of futurism and sci-fi played a role in these earliest musical experiments. There’s no doubt that this outlook was, to an extent, a reaction to the post-industrial landscape of Detroit, which had begun its much-discussed decline by the early ’80s. Atkins has cited the influence of American writer Alvin Toffler too, whose book Future Shock he’d studied as a teen, and whose writings inspired the fledgling genre’s name.

This tendency toward the futuristic would remain a running theme throughout techno and its numerous offshoots, found predominantly, for example, in the afro-futurism of later Detroit icons Drexciya.

By contrast, Saunderson, who grew up in New York and moved to Detroit later, was equally influenced by the soul and disco coming out of his home city. Through NYC radio he absorbed the likes of Chic and the extended remixes designed for the dancefloors of the iconic Studio 54.

Of the Belleville trio, Atkins was the first to release music, following up Cybotron’s debut with synth-pop indebted tracks such as Clear and Cosmic Cars.

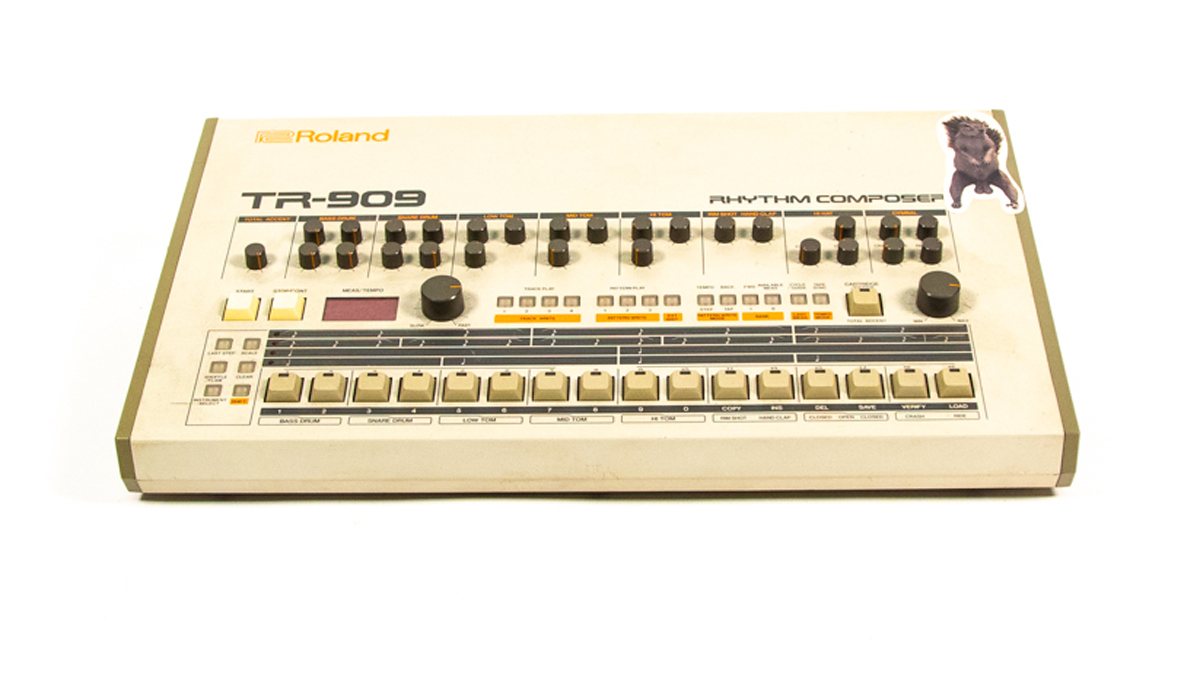

In 1985, Atkins’ collaborator Rik Davis left the group and shortly after, under the alias Model 500, Atkins released No UFO’s. Built around a punchy 909 beat, funk-style synth bass and repetitive vocal, No UFO’s is arguably the first track sonically recognisable as ‘techno’ as we know it today.

The years that followed would see the arrival of formative techno classics from each of the Belleville trio, such as Strings Of Life from Rhythim is Rhythim (May) and Good Life by Inner City (Saunderson), as well as contemporaries such as Eddie Fowlkes and Blake Baxter.

The sound, and its name, was eventually solidified with the release of the compilation Techno! The New Dance Sound Of Detroit, compiled by British journalist Neil Rushton in collaboration with the Belleville originators.

Hands on, hands off

Alongside the social and cultural influences, the impact that 1980s music hardware had on the creation of techno is inescapable. The genre’s birth coincides with the rise of ‘affordable’ music hardware, such as the synths from Korg and Sequential cited by Atkins and, most significantly, Roland’s run of iconic rhythm machines.

Techno’s style is derived from more than just the sound of these specific machines, though - it’s equally influenced by the way in which they were used. Early techno tracks were largely the work of one or two musicians, created in simple home setups rather than big, well-equipped studios. This meant that their production involved working around a lack of gear and manpower, making use of often-simplistic sequencers to loop and trigger patterns while wringing as many sounds as possible out of each instrument.

“We were using a four-track to record, when all of a sudden I just thought, ‘hang on why do I keep recording when it’s all happening live now? Why don’t I just use the four-track as a mixer and record into another tape deck?’ Chime was one of those funny things where you don’t really think about it. It turned out to be our best-selling record! I think there’s a lot to be said for doing music without any thought behind it, just slapping something together and seeing what happens. You get a good feeling, because you’ve started and finished before you’re fed up with listening to it.”

As Saunderson told FM in 1998 (FM71): “I think [The Groove That Won’t Stop] is a good example of what you can do when you get into some deep sound programming. I think that played a big part in creating Detroit’s unique sound back then; we really did spend a lot of time programming. Programming sounds is an important part of how your vision comes alive. It helps you create. You can come up with sounds which just trigger all kinds of ideas or give parts a whole new life.

“You’ve got to remember that back then we didn’t know anything, a lot of times we created something and it almost happened by accident. It wasn’t done because we were sitting down thinking through logically, it was done because we were in a creative mood working on sounds that inspired us…”

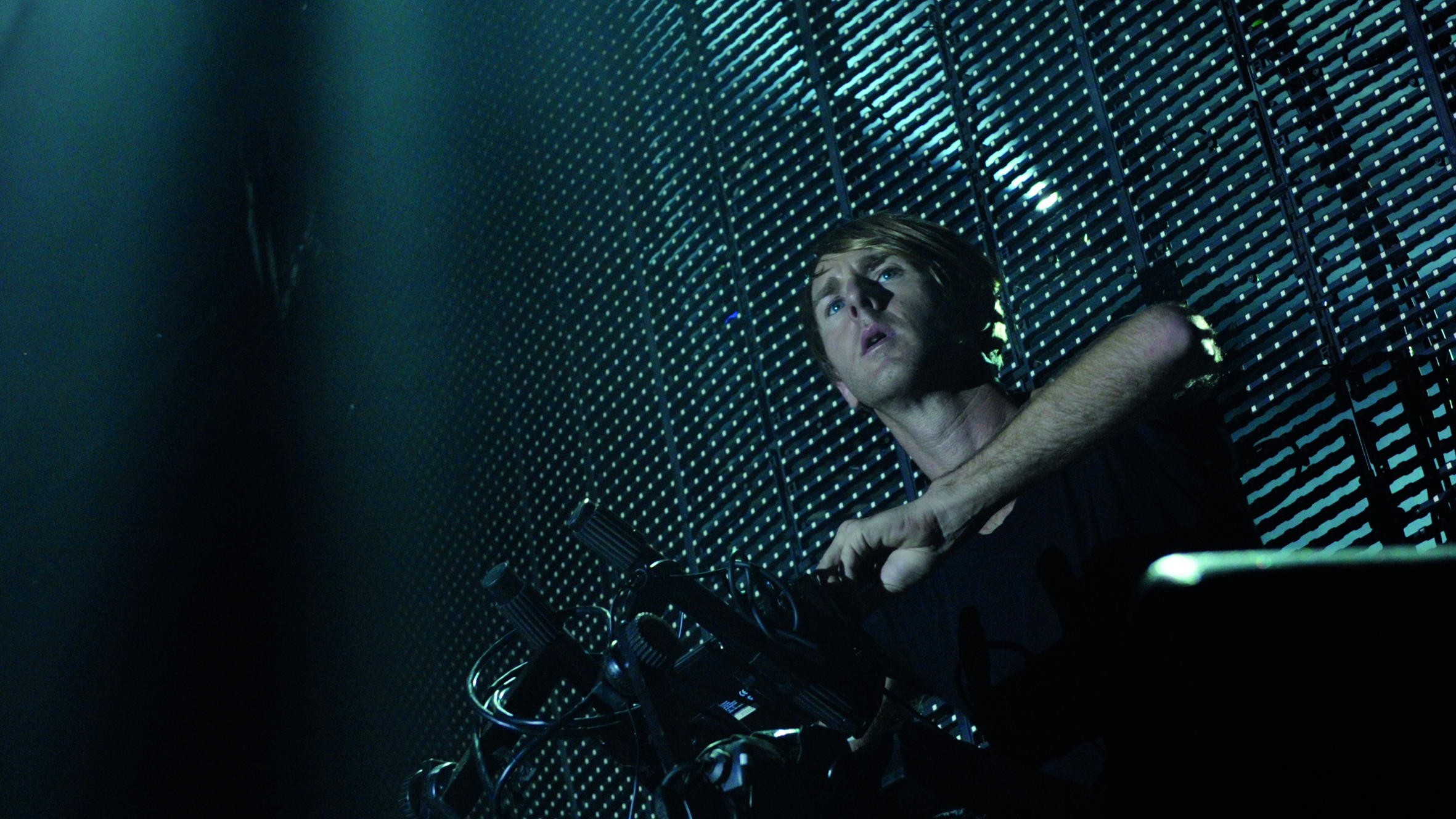

In the years following techno’s initial breakthrough, a new name rose to prominence in Detroit. Originally known by his radio DJ moniker The Wizard, Jeff Mills became popular for his mixing style, initially marked out by quick mixes between records, and later evolving to create live edits using a combination of three turntables and drum machines.

Mills explained the origins of the setup to us in 2009 (CM Special 36): “For years it had been the dream of DJs to search out really minimal tracks... things that would allow you to extend. That comes from hip-hop, where you want a fairly simple break or groove so you can then do things to it.

"The three decks thing came as a direct result of music becoming more minimal. The idea was that if it was that minimal, you could layer it together the way you’d layer tracks in the studio, and that would give you more options to create something for people to hear. I could layer three or four turntables together, because the music doesn’t change if there are no breaks, bridges or choruses. You realise that you can juggle the minimal tracks or mix them together to create a whole new track.”

Mills backs up the idea of techno being heavily inspired by the gear available at the time. “A lot of it has to do with the machines themselves,” he told FM in 2018 (FM338). “Making the analogue sequencer more regularly available and cheaper played a big role in shaping techno music – we started using these random sequences to create a certain type of sound. We’re influenced by what these machines can do, which comes down to what people design for us.”

Making the analogue sequencer more regularly available and cheaper played a big role in shaping techno music.

Jeff Mills

In 1989, Mills formed Underground Resistance with Robert Hood and ‘Mad’ Mike Banks. The group became known for their distinctive style, which was sonically hard-edged and lo-fi, with a propensity for anti-establishment and anti-corporate statements that tapped into the same class and race tensions as those explored by hip-hop contemporaries Public Enemy.

In 1994, UR member Robert Hood would go on to release Minimal Nation, a foundational blueprint for minimal techno, an offshoot that distilled the genre’s machine-driven rhythms down to their purest form.

With tracks based around just one or two synth riffs and stripped-back drums, Minimal Nation put the production emphasis on the grooves and subtle shifts in sound. It was a style that would be highly influential on later artists like Richie Hawtin.

The Berlin connection

As techno spread from Detroit in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, it quickly found popularity in the UK, tying into the burgeoning acid house scene and inspiring artists such as A Guy Called Gerald and 808 State and later the likes of Kirk Degiorgio, The Black Dog and many others.

As Degiorgio explained in 2013, as the UK scene established itself, it quickly created a relationship with the second generation of techno artists emerging in Detroit.

“Shut Up and Dance sampled Carl Craig so he sampled them back. There was a lot of that. [Craig] loved the stuff we were doing and licensed some of it for Planet E. The third release on [Degiorgio’s label] A.R.T. was from him before he was as well known. It really was the birth of it all.”

While the genre was popular in the UK and elsewhere in Europe - such as Belgium, where the label R&S became a significant supporter - it was Berlin that quickly established itself as techno’s second city.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and a new mood of open-mindedness created the perfect breeding ground for techno’s anti-establishment and futuristic undertones and sense of sonic adventurousness.

“I would say don’t overcomplicate things. Create something that feels right to you that has a pure, honest energy and is infectious.

"An example of that is when I spent three or four days with the engineer explaining the patchbay to me. He showed me all these great effects, but I was like, no, fuck it, put all the effects in mono please - I want eight mono sends with everything coming back to the board so I can do feedback loops and EQ the hell out of them with minimal panning. It’s about making a track that feels good.”

Dimitri Hegemann, founder of Berlin Atonal festival, is credited with first introducing the pioneers of techno to Berlin in the mid-’80s. It was in ’89, however, that the scene really took root; a year that saw the first ever Love Parade - and its influential afterparty at Hegemann’s Ufo club - as well as Mark Ernestus founding the influential Hard Wax record store.

As well as being one of the most important importers of techno records with Hard Wax, Ernestus would have a huge impact on the genre as one half of pioneering dub techno outfit Basic Channel, alongside Moritz von Oswald (among numerous other aliases the duo worked under).

Structurally, dub techno bears similarities to the minimal sound Robert Hood was refining across the Atlantic - both representing the genre at its most loop-centric and groove driven. However, whereas Minimal Nation made use of few effects - mostly a simple touch of reverb - the dub techno of Basic Channel makes liberal use of delays, reverbs and modulation effects to create a more spaced-out take on the sound.

The ‘dub’ in the name comes from the hardware-heavy process of ‘live remixing’ adopted from reggae - a genre link Ernestus and von Oswald would explore more thoroughly as Rhythm and Sound - and the heavy use of tape echoes such as the Roland RE-201 imparted most tracks with a muffled, bassy quality and a soothing coat of tape hiss.

As dub techno progressed, another defining trait was the often low-level of the percussion - whereby kicks, snares and hats would take a back seat to pulsating synth chords and delayed stabs.

The origins of Berlin techno didn’t happen in isolation from the genre’s origins though. By the early ‘90s Berlin artists like von Oswald were regularly collaborating with Detroit artists, creating what was often known as the ‘Berlin-Detroit axis’.

After the Ufo club closed in 1990, Hegemann opened Tresor in part of a former department store near the city’s Potsdamer Platz. The club, along with its associated record label, would go on to play a major role in making Berlin a global mecca for techno fans and aspiring producers.

Over the years, techno artists from all over the world have relocated to Berlin, from Richie Hawtin to modern luminaries such as Objekt, Blawan and PAN-founder Bill Kouligas.

The ‘Berghain sound’

In recent times, Berlin techno has been synonymous with Berghain - a club world-famous for its unpredictable door policy as much as its music - and its associated label, Ostgut Ton.

The ‘Berghain sound’ (if there is one), is probably most closely associated with artists such as Ben Klock and Marcel Dettmann, whose atmospheric but tough tracks play like a more industrial update to the dub techno of ‘90s Berlin. It’s a take on the genre that puts the kick at the forefront, too, often using sub-heavy, reverb-drenched drums as both rhythmic backbone and bassline.

The percussion in modern Berlin techno often has a sound designed to match the post-industrial clubs where tracks are regularly played - effect treatments are dark and cavernous, bringing to mind spaces like the former powerplant that houses Berghain’s main dancefloor.

Speaking to FM in 2019, Berghain regular Fiedel shared his secrets to creating tough, Berlin-style drums.

“As a source I sometimes use the Max For Live Drum Synth plugin, and sometimes I use [Live’s] onboard drums like the 808s or 909s. I’ll layer drums, though, in order to separate the lower and higher parts so I can focus on the low end. I’ll have the same drums - for example a 909 - split into two so I can shape both elements separately.

Then, to create powerful drums, of course, you have to compress them and limit them. That’s the key to making sure you can hear them and feel them in the club.”

It’s no coincidence that, alongside its long history as a hub for techno artists, Berlin is also home to several significant music technology brands. The crossover between the genre and those creating new music technology has always been strong in the city - Ableton co-founders Gerhard Behles and Robert Henke were both members of minimal techno outfit Monolake at the time of the company’s launch, and Native Instruments has employed a number of notable DJs such as Objekt and Errorsmith, the latter of whom developed the company’s excellent Razor synth.

In a neat bit of reciprocation, both companies have significantly advanced the ways in which techno is produced in the 21st century. NI software such as Reaktor, Massive and Kontakt are key tools for creating the textural, often-atonal sounds used in modern techno. With its hybrid take on the classic MPC format, Maschine is a prime conduit for the genre’s hands-on ethos.

Ableton Live, meanwhile, has become the de facto DAW of choice for modern techno producers thanks to its loop-focused workflow and non-linear approach (although it’s by no means the only viable option).

These, along with the likes of Bitwig and modular mainstay Schneidersladen – and its Superbooth trade show – mean that Berlin remains a prime spot for adventurous music makers and technologists alike.

Roland domination

It’s difficult to talk about most electronic genres without eventually mentioning Roland’s 1980s machines, but the links between the Japanese brand and techno are arguably tighter than with any other genre.

The TR-909 is effectively the foundational machine of the genre; its sounds and workflow inspired the earliest Detroit techno releases and it remains the go-to rhythm machine today.

Jeff Mills, an undisputed master of the 909, explained its appeal in FM 338: “its sounds are kind of party-ready. They’re so distinctive and have just the right amount of resonance and tuning that you don’t need to put effects on them to make them sound great.

"It’s also a really powerful machine that came along at a time when music needed to be powerful. This was during the rave era and electronic and techno music, where you often needed the drums to be very strong.

"The 909 was always ready to go, straight out of the box, which is different from the 808 where some sounds are a bit soft. On that machine, the tuning is interesting on the kick drum, but when you need to hammer the sound it doesn’t have that type of dynamic.”

Sven Väth voiced a similar opinion back in 2002 (FM122): “I think the 909 is so enduring because somehow you have a relationship with the machine. There are certain sounds you always remember. We sample it a lot as well, especially the bass drums, and then distort and loop them.

"But even so, a good 909 kick is still a good 909 kick. Also the hi-hats, they’re just unique. They give the tracks that techno feel because old techno always had those sounds.”

It’s not just the 909 that has had a major impact on the creation of techno though. The TB-303, obviously, is the cornerstone of acid, first misused to iconic effect by Chicago outfit Phuture, while the SH-101 has long been a techno favourite, thanks largely to its simple but hands-on workflow.

As Richie Hawtin put it in 2016 (FM301): “The 101, honestly... You can have all the most amazing synths with as many knobs as you want, but you only have so many hands. I did, and still do, gravitate to simplistic machines that I can get something out of very quickly.”

The 101 was among the Roland gear instrumental to the creation of Daniel Avery’s ambient techno modern classic Song For Alpha, too, as he told us in 2018 (FM330): “I bought an 808 and those long, drawn-out kicks feature heavily. For pads, finding a Roland JX-3P and running it through a series of different reverb units instantly made a huge difference in the studio. The 101 was used a lot again this time and the sound of it will never not be totally satisfying.”

It would be a misnomer to suggest that techno production is simply a case of using one specific set of retro instruments. The genre’s sound and evolution comes down as much to the way that musicians interacted with these – if we’re being honest – fairly limited machines, as much as the sounds themselves.

As Glasgow techno pioneers Slam told FM in 1998 (FM71): “Techno is all about exploring the machinery. It doesn’t matter if you don’t have [a 909 or 303]. What matters is your attitude. If you’re willing to push beyond the boundaries and make original, innovative music, to push the machines to their utmost, that’s techno in its purest form.”

Innovation and exploration

While, as with other electronic genres, you could certainly accuse some techno producers of being overly obsessed with retro gear from the heyday of analogue, there has also always been a strong trend toward innovation within the genre.

Hawtin is a prime example, having been instrumental in the formative days of digital DJing with his early adoption of Final Scratch and Ableton Live, through several innovative interactive live tours and, in recent years, launching his own MODEL 1 DJ mixer.

As sampling and digital technology began to become commonplace in the ‘90s, techno producers were quick to make use of it to adventurous ends. Compared to genres like house, where samples are often used as wholesale loops, techno production tends to involve more oddball creative processing and manipulation.

As Dutch pioneer Speedy J explained of his process in 1997 (FM57): “I like shaping sound and inventing new textures and always record while I’m doing it. I’ll play something, loop it with the sequencer, and keep shaping it until I’m happy with it. The whole process has interesting results or will have useful parts in it. Then I will sample bits from that again, treat it again and again. I have a huge library of my own sounds to work from.”

“A lot of it is about the relationship with the machine. The different characteristics you get with them. If you come from this era, you can probably get the same kind of feeling from software, but for us it’s like, this 909, not only does it sound different but there’s a way it reacts differently. Like, a particular synth has an individual way it reacts; it’s the quirks, the little nuances.”

It’s this sort of adventurous approach that has made techno one of the prime drivers behind the rise of modular synthesis in recent years. With its emphasis on rhythmic triggering, modulation and complex interaction, modular synthesis is a seemingly perfect match for a genre like techno.

Berlin-based artist Rebekah explained its appeal to FM in 2020: “With soft synths I was always trying to find a proper raw techno sound, but found it a real struggle. With modular you have to learn the lingo but the sound is instant - and the sound I wanted was in the modular realm. With soft synths, I have to do a lot more layering and adding distortion.”

So, what’s the key to creating the perfect production setup for techno? As we’ve seen, vintage Roland sounds are a solid starting point, although by no means mandatory. There are countless solid software recreations these days, with Roland’s own Cloud service providing the most convenient bundle.

In hardware, Behringer’s remakes offer cheap authenticity, although, for us, Roland’s TR-8S is the best balance of vintage vibe and modern flexibility.

Whether you’re using hardware or software, the ability to get hands-on is key. As Ostgut Ton mainstay (and owner of an enviable synth-stuffed studio) Steffi explained to FM in 2017, studio layout is key to her workflow.

“I guess I just like to get everything laid out before I record. When I stepped away from the computer and found my love of hardware sequencing, for me that was a way to connect all my instruments. The desk has a very important role in that, because if I had to record each sound separately, you kind of lose the moment. It’s all about pushing the fader, seeing what it does, putting some effect on it, then moving on. I feel if you’re loading everything into a computer then, for me, it becomes static.”

Sequencing remains a key element of techno creation, too. In the software realm, something like Bitwig Studio, with its modular ‘Grid’ system, offers a mass of modern sequencing tools, as does the wealth of free and commercial tools available for Reaktor or Max (now integrated into Ableton Live).

Even setting aside the near endless possibilities offered by Eurorack, it’s a boom time for hardware sequencing though, thanks to innovative and easily integrated tools such as Korg’s SQ-64, Pioneer DJ’s Squid or Arturia’s excellent ‘step’ range.

As 808 State’s Graham Massey told us in 2019 (FM349): “The BeatStep Pro plays a huge part due to its tight CV/gate sequencing. You know those drawings by Escher where you can’t tell whether you’re going up the stairs or down? It gave rise to these weird earworms – patterns that move around and give a tweaky aspect to the record.”

As was the case for those Detroit originators, learning the ins-and-outs of an instrument remains the key to getting the most out of it. As Bloody Mary said in 2020: “If I’m using the Access Virus, say, I’ll go to the studio and work only using that. I’ll just play with the synth, jam and make crazy noises using the LFO and all the frequencies and try to get the best that I can from just one sound. I’d say it’s better to know exactly what you can get from the gear you’re working with. It’s not a competition. I would love to have more gear in my studio, obviously, but if you really work with one piece you’ll be surprised what you can take from it.”

Into the future

In 2021 techno is still a huge global force, albeit one that sits somewhat outside of the mainstream. While clubnights and festivals from outfits like Drumcode - the world-conquering label run by Swedish producer Adam Beyer - can sell out arena-sized venues for multiple nights, in the public consciousness, techno is still a mysterious subculture, often misused as a byword for any and all electronic music. Indeed, much of the most exciting music comes out of underground circles, from the leftfield bass of UK labels like Livity Sound or Perc Trax to the playful hard-edged sounds of up-and-coming artists like VTSS.

As Kevin Saunderson told us in 1998: “When Juan, Derrick and I first set out on this thing, we had no idea what would happen. I could never have imagined how it would turn out. But no doubt what we did back then changed the world.”

Want more synthy goodness? Get all our features, tutorials, tips and more at our Synth Week 2022 hub page.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

MusicRadar deals of the week: Enjoy a mind-blowing $600 off a full-fat Gibson Les Paul, £500 off Kirk Hammett's Epiphone Greeny, and so much more

“A well spec’d device that bridges the gap between a basic stereo field recorder and a more advanced multitrack device”: Zoom H4 Essential review