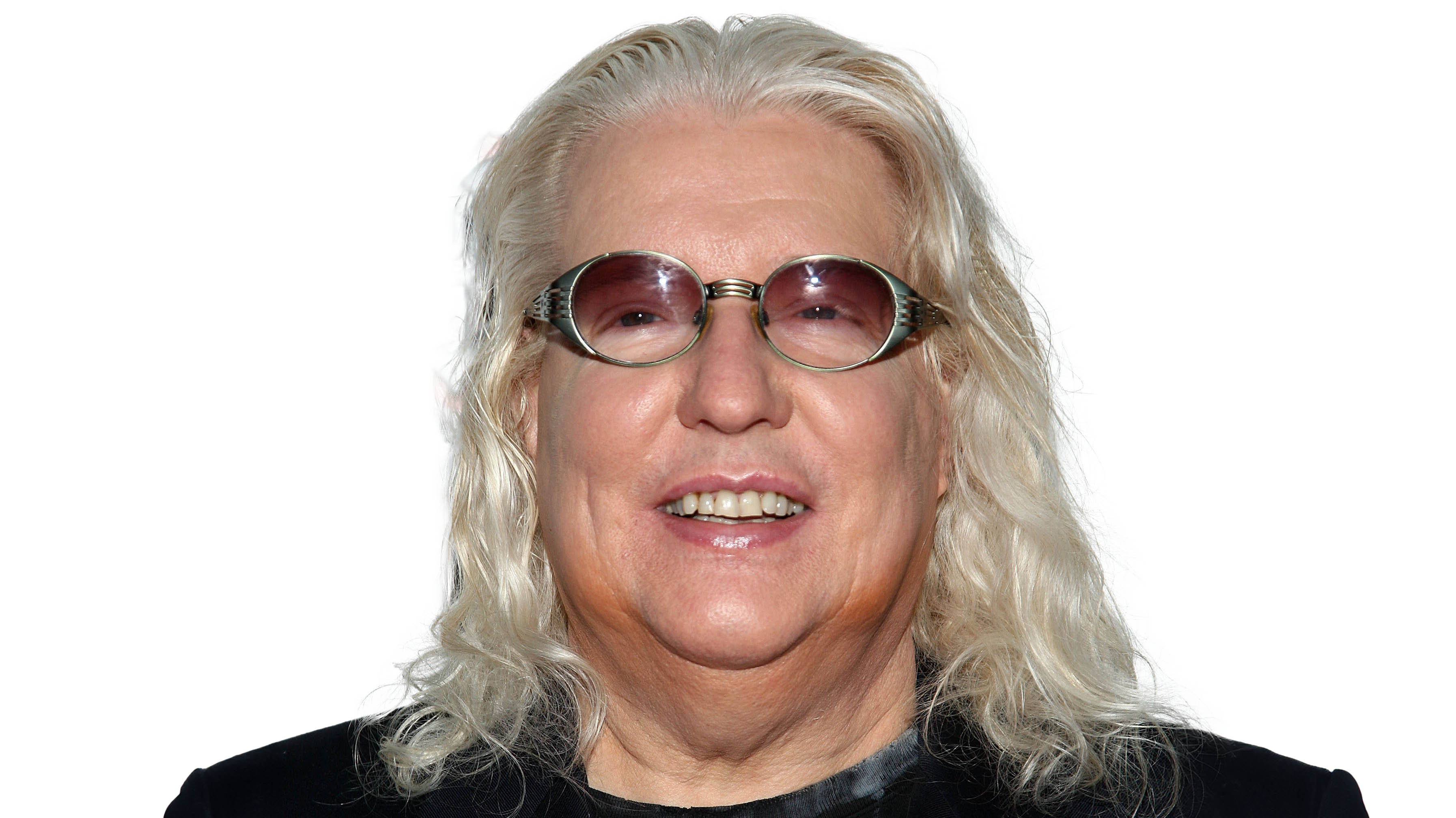

"Everybody around me kept saying, 'Norm, you can't carry on like this'": Fatboy Slim's career in gear, from tape to Atari to Ableton

25 years on from Slim's iconic second album, we take a backwards glance at Norman Cook's music-making evolution

Norman Cook, aka Fatboy Slim, has 'come a long way' since starting out as a Brighton DJ in the early 80s. He led the big beat charge, became an international superstar DJ, remixed just about everyone you can think of, sold millions of albums and scored hits around the world with tracks like The Rockafeller Skank and Praise You.

So many achievements, in fact, that you almost forget that he once led a strange, parallel life in The Housemartins for four years, enjoying hits like Caravan of Love along the way.

From avoiding the computer to embracing an Atari, Norm's studio has changed as the tech has ebbed and flowed

On the 25th anniversary (yes, really) of his five million-selling (yes, really) album You've Come A Long Way, Baby, we thought it an appropriate time to examine the Fatboy Slim studio and how it has changed over the years: from avoiding the computer to embracing an Atari, and from early sampling to remixing the stars, Norm's studio has changed as the tech has ebbed and flowed.

So let's look at those Fatboy Slim 'years in gear'. And as we begin the journey, we're stepping back even further in time to the 1980s.

The '80s

In 1984 Cook was a rising DJ and remixer in Brighton, UK, but got a call from school friend Paul Heaton asking him to play bass in The Housemartins. That would mean a four-year break from remixing and DJing as the Housemartins were very much an acoustic and pop outfit, and Cook was unable to pursue his more electronic passions.

There were arguments about what I could do without damaging the Housemartins. In the end, I wasn't really allowed to do anything

Norman Cook

"I put the remixing on hold when I joined", he told Music Technology magazine in 1988. "The band said 'the Housemartins aren't associated with that kind of music, you can't do it'. There were arguments about what I could do without damaging the Housemartins and, in the end, I wasn't really allowed to do anything." After the Housemartins split in '88, though, Norman was able to return to his first love, so assembled a studio based around a 16-track Fostex E16 tape recorder. Cook would remix tracks by isolating individual song parts on the original multitracks and sampling them, or by using 'vicious' EQ-ing if the multitrack wasn't available.

Remixing was a complex and tortuous process back then, and sampling in those days was very much in its infancy too, leading to all of those early debates on the ethics of sampling versus using other people's melodic hooks. Cook certainly knew where he stood compared to the other big producers of the time, like Stock, Aitken and Waterman.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"They say it's wrong to sample other people's sounds, but it's alright to rip off other people's ideas and tunes. Every time you do anything musical you're copying somebody else. If you play a conventional drum kit, you're playing it in the way you've heard other people play it. Also, if you just rip off someone's idea you're not crediting them for it; if you use a sample of their voice, everyone knows it's them. You've only got to look at James Brown and Ofra Haza to see how their careers have been launched or relaunched by people's usage of them."

After making his mark remixing the likes of Eric B. & Rakim, James Brown and even The Osmonds, Cook had his first success with the track Blame It on the Bassline, the video of which is… very much of its time.

Early successes

Interestingly, Cook's setup at this time was mostly hardware, although he'd used what he called 'The Steinberg' for sequencing (which we'll assume was someone else's Creator on an Atari). However, he preferred a mostly Roland setup for his sampling and sequencing – an MC-500 sequencer, S-10 sampler, plus some classic synths and drum machines in the form of the JX-3P, TR-808 and TR-626 – and used those over an Akai S900 sampler and Steinberg sequencer.

I'm really anti too much technology. I didn't want to fall into that trap - that's why I haven't got a computer

Norman Cook, 1988

"I'm really anti too much technology. The Steinberg does too much for me. I'm happy with an old-fashioned sequencer. You can take technology too far. People have different ideas of what is 'too far', but it's easy to forget that you're trying to make a song that sounds good. I was scared when I set the studio up because I didn't want to fall into that trap - that's why I haven't got a computer."

Cook would feature in various acts in the 90s like Pizzaman, The Mighty Dub Katz and Freak Power, but found most success with Beats International and the excellent number-one single Dub Be Good to Me.

Fatboy Slim

In 1996 Cook created the 'goofy and ironically' named Fatboy Slim persona. While championing the then new big beat genre, he signed to Skint Records to release the debut Slim album Better Living Through Chemistry. It was notable for the track Going Out of My Head, the epitome of big beat with huge riffs and even bigger beats (of course).

These were all laid over massive guitar, vocal and drum samples, including Led Zeppelin and Yvonne Elliman's cover version of I Can't Explain, which led to The Who's Pete Townsend being given a songwriting credit on the track.

The epitome of big beat were the huge riffs and even bigger beats, all laid over massive guitar, vocal and drum samples

Even though he'd have to share the credits, the song would do enough to put Slim's music in both movies and back in the charts. Meanwhile the track Everybody Needs a 303 became the anthem for gear nerds everywhere, celebrating the iconic piece of Roland equipment that everyone wanted to get their hands on in the 1990s (and to this day, come to mention it).

Ironically, while the beats are big and the arrangement is frantic, the actual 303 is initially outshone by a more acoustic but insistent acoustic bass sample before the Roland bassline completely swamps the song – as TB-303s tend to do – from a couple of minutes onwards.

You've Come a Long Way, Baby

On October 19th 1998, Fatboy's Slim's second album, You've Come a Long Way, Baby was released. Even though Cook had enjoyed successes with a variety of acts by then, nothing could prepare him for the millions of sales and the success of the tracks The Rockafeller Skank, Right Here, Right Now and Praise You which all charted globally.

"I’d hit the formula, of what was, by then, called ‘big beat’," he has said of the time. "A lot of the underground club stuff was great, but they were missing that verse/chorus, verse/chorus, middle eight. I’d been in enough pop bands over the years to know that’s how it worked."

Cook had also mastered the art of the drop and the build, leading to those famous hands-in-the-air moments that have marked out many a Brighton beach party.

“I wanted to take this music out of the nightclubs and onto the radio," Cook said. "So I took all of those dancefloor ingredients, but arranged them in a manner that the human brain would associate with pop music. That was one of the many things I learned by the time I got to this album.”

By this time Cook had, of course, moved on with his studio gear and finally embraced the computer, although he was sill using an Atari with C-Lab Creator software (that would eventually become Logic).

Cook was also still using mainly hardware and you can spot a good deal of this in this later video from 2016 in which he describes how he put together The Rockafeller Skank.

We can see a Studio Electronics rackmount MiniMoog clone, Roland TR-909, Phat-Boy MIDI controller, classic Roland Space Echo delay, Eventide Harmonizer, Nord Lead rack synth and, of course, a bunch of Akai samplers and a Roland TB-303.

"By today's standards it [the Atari and Creator set-up] is very rudimentary but it did everything you could do," he said in 2016. looking back at The Rockafeller Skank. "When the drum machine, this [the Atari] and the sampler became accessible to us, that was when you could get the funk just by using drum loops and samples rather than pretending to be Bootsy Collins on the bass."

- Read more: Fatboy Slim on You've Come a Long Way, Baby: "At this point, I’d cracked the big ‘drug build’"

The slimmed-down setup

From around 2012, Norman Cook slimmed down everything, giving up drink and other 'naughty substances' and embracing a more laptop-based studio setup.

Everybody around me kept saying, 'Norm, you can't carry on like this'

Norman Cook, 2012

"It wasn't my idea at all," he told Future Music. I was completely happy working with the Atari and the Akais, but everybody around me kept saying, 'Norm, you can't carry on like this'. I suppose I was bullied into it by my management. They just kept pointing out all the positives of Ableton. The way you can lash bits of songs together. I think I was scared of changing things, just in case it didn't work as well as what I was used to."

Even at this point Norman wasn't entirely convinced about the Ableton route going forward and would still boot up his Atari.

"I switched on the laptop, looked at the screen for several hours and then thought, 'Nah, let's go upstairs'. I hadn't switched on the Atari for months, but it felt great. I dug out my floppy discs, dusted everything down and just started playing loads of samples."

He was, however, getting to grips with Ableton Live and seeing its potential.

"Yes, I am a bit of a moaning old Luddite, but I'm not against 'change' per se. I don't think that the Atari and the Akai are the only legitimate tools to make music. Ableton is a fantastic piece of kit. I just haven't found a way to link my creative urges to working with a laptop. It'll come. I'm almost there."

However, it does seem that this epiphany was short lived, and that this introduction to the vast world of synths and other soft options might have been Cook's undoing when it came to producing more music.

In 2022 he told Synth History: "I always love the old gear more than the new gear. I find it more inspiring. When you're making electronic music, I think the most inspiring times are when people had very limited equipment and it was what you could squeeze out of that."

"That is one of the reasons I don't make so much music anymore," he continued, before talking about those too many options. "It's got every single drum machine, every single synth sound, every single - potentially - sound known to man, every record that's ever been released. And they're all there. And I just sit and go, ‘pfft, where do you start?’”

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.

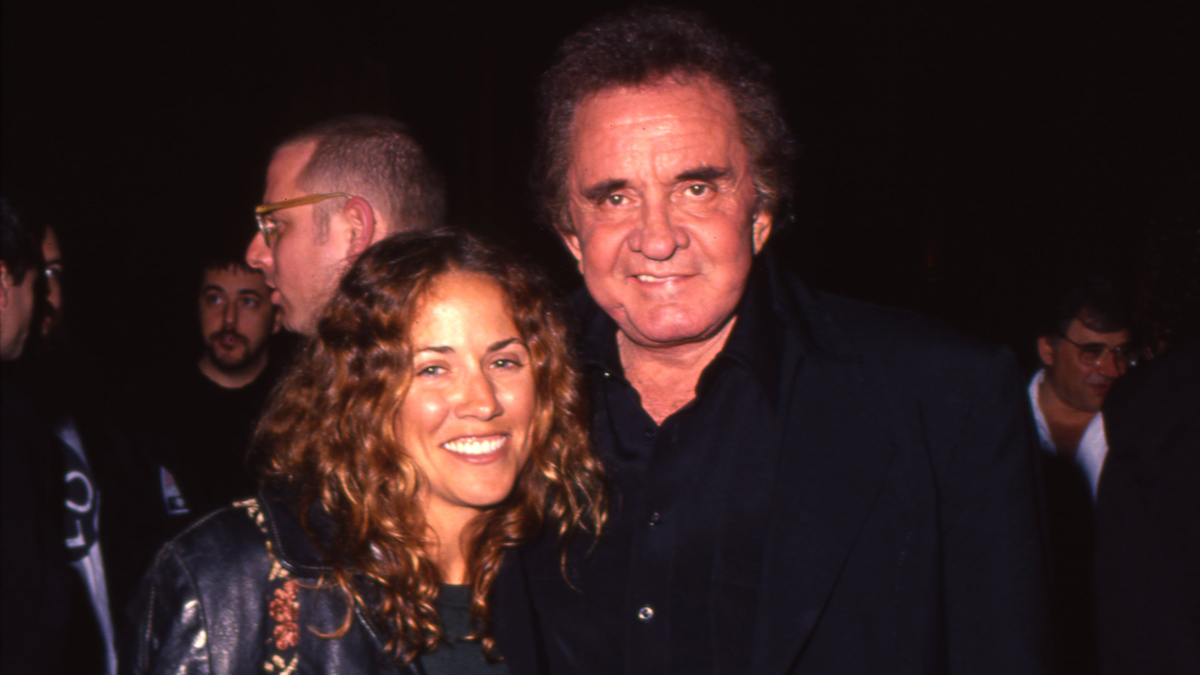

“So I’m standing in the vocal booth one night and I felt Johnny’s presence. I am not a woo-woo, but I felt his presence pushing me": Sheryl Crow says it felt like Johnny Cash was with her when she recorded her vocals for their posthumous duet

“Chris, that’s not how it goes”: Chris Martin does his best Bruno Mars impression as Rosé joins Coldplay on stage to perform APT in South Korea