18 superstar guitarists ask Hank Marvin their burning questions

Brian May, Peter Frampton, Steve Howe and more pick the pioneering picker's brain

Introduction

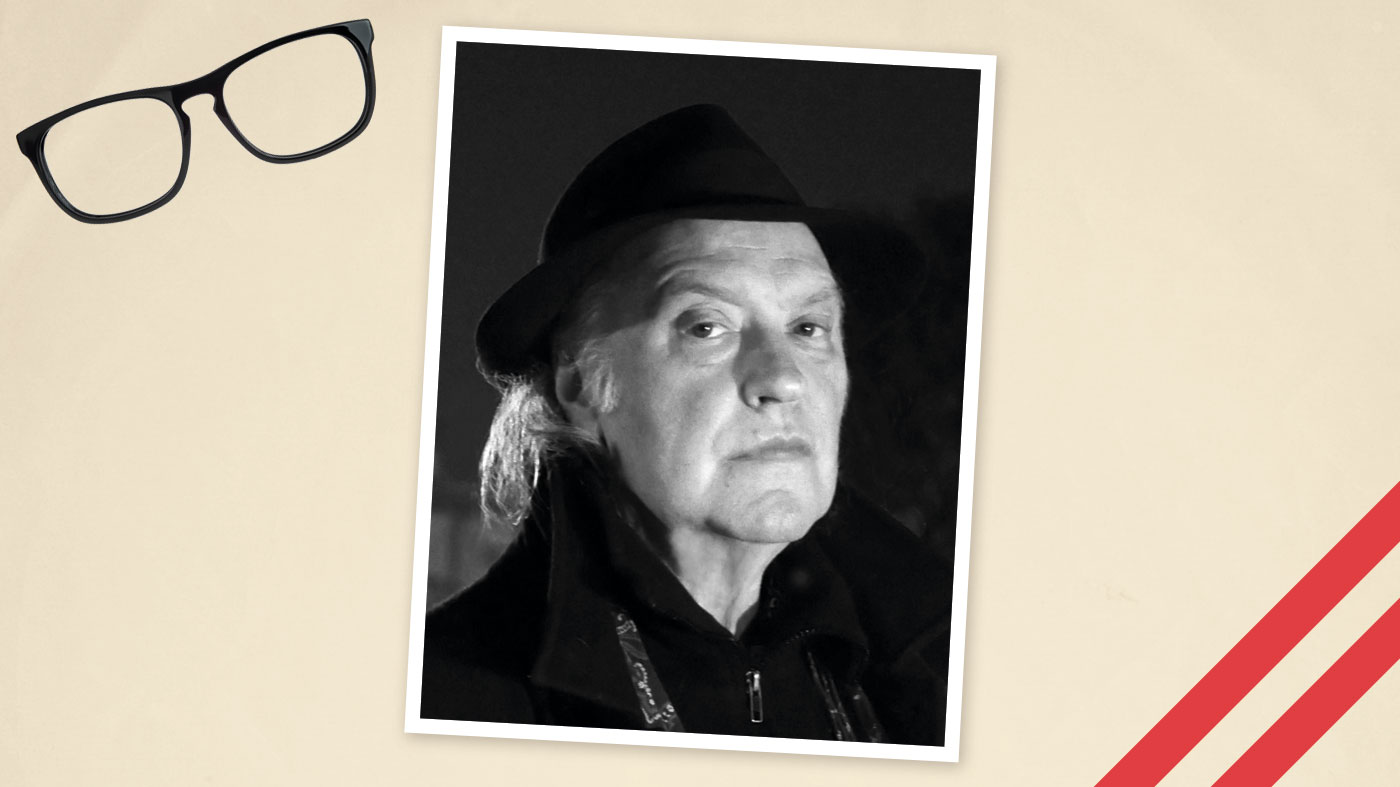

Hank Marvin has influenced the greatest guitarists of all time, so with a new album just announced, who better to quiz their hero on his playing, influences and gear than the guitarists themselves?

Hank Marvin’s new album, Without A Word, is one of the best of his 16 solo releases so far. Co-produced by Hank with son Ben, it brims with beautifully played instrumental versions of some of the ex-Shadow’s favourite melodies. Most feature Ben and Hank’s Gypsy jazz cohort Gary Taylor on acoustic rhythm guitars, with a production that’s modern, crisp and instantly pleasing.

For this album, I was flicking over to the neck pickup and cranking the amp for the solos, just enough to make it sing

Hank is on top form, bringing every nuance of his envious melodic style to bear, with guitar tones both familiar and surprising. You don’t expect to hear him say, “Yes, we put the Tube Screamer on for that one,” but these days the Twangmeister is all for a bit of sonic change. “It’s adding another tone colour to the music,” he says.

“I’ve found that sometimes when I get to some of the solos on numbers I’ve been doing since the early 90s, to play it with my normal ‘clean’ sound leaves something wanting. If I crank the amp a little, I get a bit more sustain and can do a little more with it. More voice-like, if you like.

“For this album, I was flicking over to the neck pickup and cranking the amp for the solos, just enough to make it sing. On Don’t Get Around Much Anymore, that’s a very nasty crunch, but it did seem to suit the number. It’s like, ‘Wow, I’ve suddenly got a Tom Jones voice here.’”

That’s not to say there’s not plenty of Hank’s delicious ‘plummy’ clean tones. But this time he wanted to get more experimental, with several tracks featuring pickup changes, some of Hank’s beloved Gypsy jazz influence and even some tasty bluesy licks. Blues licks? Oh yes, Hank loves blues guitarists, too.

“A lot of them,” he affirms. “One of the first guys I heard playing electric blues, funnily enough, was Eric Clapton with the Blues Breakers. Then Peter Green, very tasty player. Suddenly, I was aware of the original American blues players like BB King, Albert King, Freddie King.

“Of course, you had the new wave come along - Robert Cray, and Stevie Ray Vaughan was wonderful. I love to hear guys who can not only play with feel and dynamics, but have some technique to back it up; it means they’re not just playing the same basic licks over and over again. Gary Moore, for example, was an outstanding blues-rock player. Robben Ford, I like his stuff as well.”

However, since our first interview with the great man back in ’95 (with this self-same writer), we’ve asked and he’s answered every conceivable question. So… we put the feelers out to some fine players who admit to a bit of Shads in their own musical DNA, to ask some for us.

Six-string luminaries Brian May, Peter Frampton, Steve(s) Howe, Hackett and Lukather, Bill Nelson, Dave Davies, Guthrie Govan, Phil(s) Manzanera and Hilborne, Martin Taylor, Darrel Higham, Carl Verheyen, Marty Wilde, Andy Powell, Gordon Giltrap, John Jorgenson and Richard Hawley didn’t wait a second getting back to us.

Hank has answered their questions with his usual blend of humour, honesty and humility, so pick up that Red Strat, sit back and read on…

Brian May asks:

As you know, I’ve been inspired by The Shadows all my life. The very first track on your very first album was called Shadoogie, and on the face of it, it was a rendition of a traditional boogie 12-bar blues.

Our dear, departed friend Bert Weedon played a simple version called Guitar Boogie Shuffle. But your track is beyond astounding. It’s different from anything that had gone before… almost a declaration that The Shadows were in a different league of creativity and excitement - a new universe.

Shadoogie is beyond astounding. It’s different from anything that had gone before

The track opens with an original build-up on the B chord, and then the main riff kicks in and within seconds we are blown away. The riff is so complex and yet flows off your fingers apparently so effortlessly and so locked in.

The whole band is glued as if you’d played this already a thousand times before recording it. The production is immense, your massive clang on the lead guitar setting a benchmark that’s never been equalled. The drums are huge and enveloping, the bass is thunderous, and the rhythm guitar (as Bruce [Welch] always was and is) immaculate.

The whole thing sounds so incredibly evolved and steams through like a juggernaut. HOW DID YOU GUYS DO THAT? How did you become so flawlessly epic so fast? What inspired you? Cheers, Hank. Honoured to know you.

Hank Marvin replies:

Hi Brian. The thing is, in those days it was very different from recording now. We all played together, live, and the expectation of EMI Records was three sides in a three-hour session.

You just hope you can play as an individual well enough not to let your colleagues down

So we recorded 12 tracks in two days, in four sessions. And that was the album. So you just played it: there was the adrenaline rush, a certain amount of nerves - the red light is on, and we all know about that one - and you play.

You just hope you can play as an individual well enough not to let your colleagues down, that as an ensemble you can play well enough so it sounds as if you’re all in the same ballpark, as regards timing, feel and everything.

Naturally, we’d done our arrangements, but that was it - you just played it and all those factors come to the fore and sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. And when Norrie [Paramor, producer] was, ‘Oh that’s great guys, thanks,’ we’d go, ‘Phew.’ It was relief - we’ve done it. None of us knew it would have such an impact on a young Brian May. But I’m glad it did, because you inspire me with your playing.

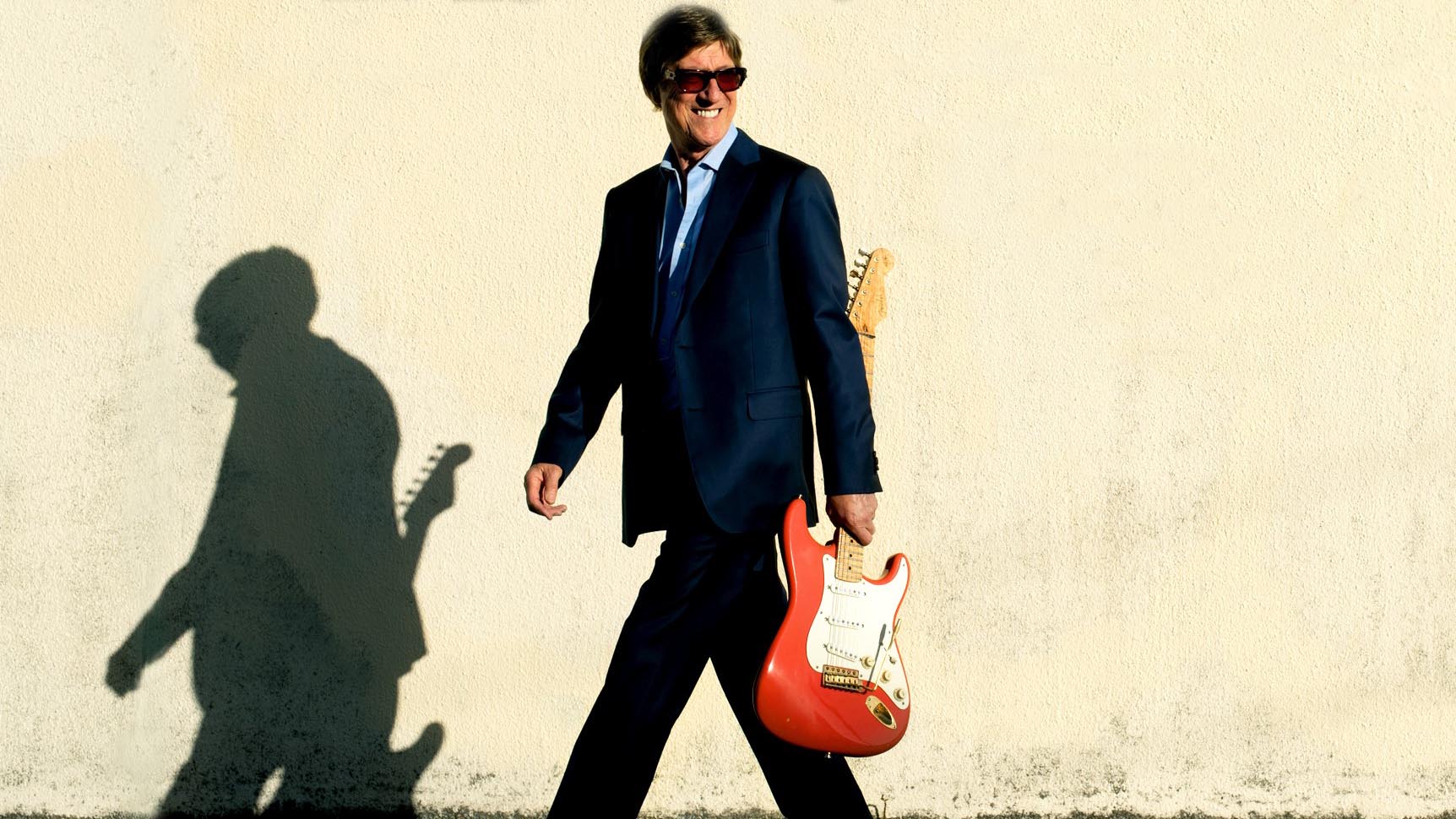

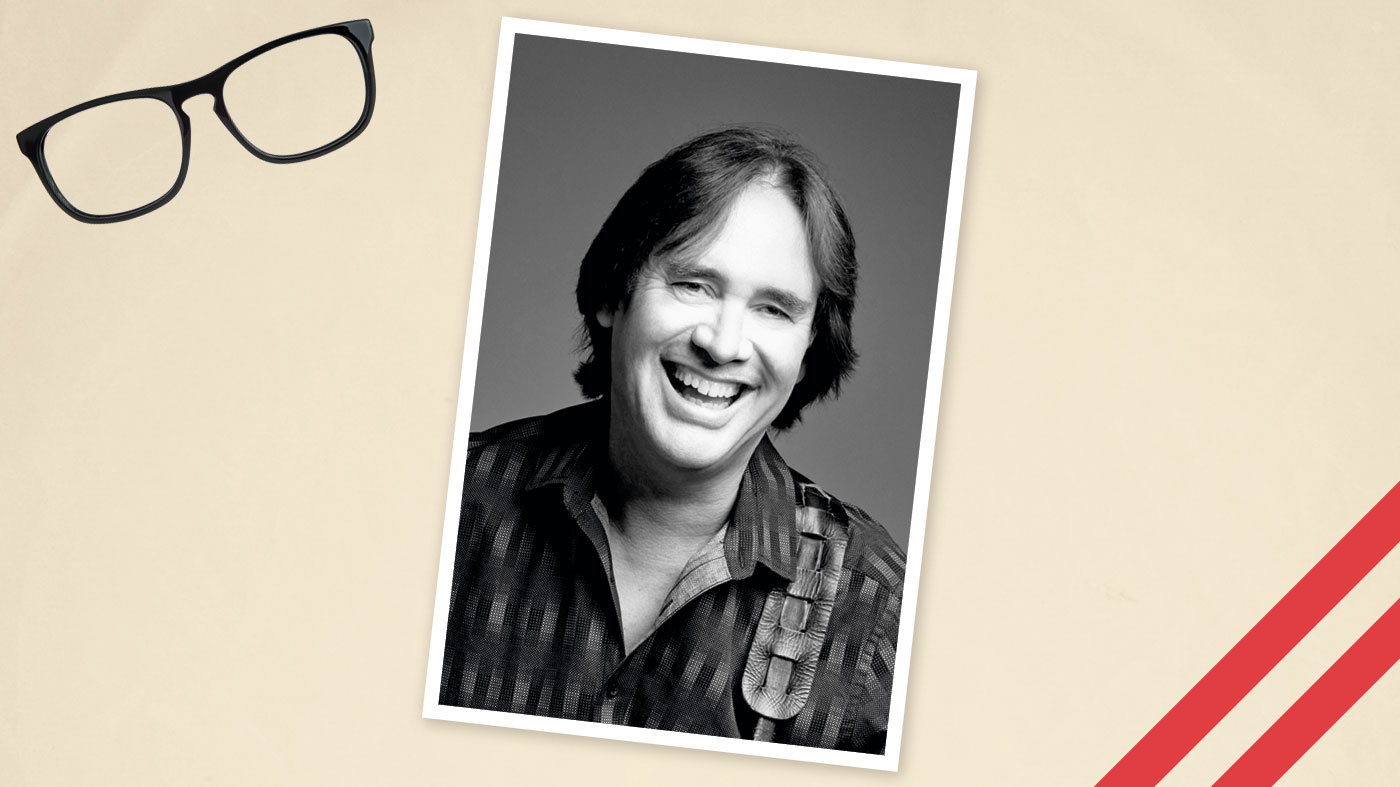

Peter Frampton asks:

I was doing a session for Cliff recently in Nashville and he told me the story of the original Fender Strat.

Is there a possibility you might play that original Strat again? I used to draw it during maths class!

He said you ordered a sunburst one, like Buddy Holly’s, but how the famous red one arrived instead. He said Bruce has that one now. Is there a possibility you might play that one again? I used to draw it during maths class!

Hank replies:

We called it Flamingo Pink, but the guy said it was Fiesta Red

Hi Peter. Actually, we didn’t order a sunburst one… we called it Flamingo Pink, but the guy said it was Fiesta Red. So we ordered that, to be different. Bruce has the guitar now. It was a lovely guitar, and still is. But as regards ever playing it again, probably not; I’m very happy with my signature models.

It meant a great deal to me - because of the whammy bar, I developed a certain style - and obviously the sound it produced, coupled with the Vox amp and the echo, was a new sort of sound. So that played a huge part in my career.

Marty Wilde asks:

You played on so many of Cliff’s great records - which guitar solo gave you the greatest satisfaction?’

Hank replies:

Hi Marty! There’s a question. One solo that has become almost an integral part of the song is the one on Living Doll. It’s not a rock ’n’ roll solo, but it was absolutely spontaneous.

Living Doll might not be the most rock ’n’ roll solo, but it gives me a lot of pleasure because it felt very musical

Again, fear and adrenaline played a huge part. Also, it wasn’t played on a Strat. A guy that we used to know down the Two Eyes had gone to France to play with Johnny Hallyday, and he came back over to London, came to Abbey Road and we had a bit of a natter: ‘Oh, we’re doing a session, blah, blah, blah.’ And he had this big guitar case with this lovely white archtop guitar that was a copy of a Gretsch White Falcon.

I was still using my little Antoria. He said, ‘Have a play.’ By this time, we were working on Living Doll and I found, purely by chance, that if I pressed down on the tailpiece I could give it a sort of vibrato effect. So I said, ‘Can I borrow this guitar for Living Doll?’ He said, ‘Yes.’

The solo came along and I just played this double-stopped solo and everyone said, ‘That’s great.’ At the end of the tune, I did the 6th chord and I used the tailpiece to give a whammy bar effect. So while it might not be the most rock ’n’ roll solo, it gives me a lot of pleasure because it felt very musical. And there were more than three chords in it!

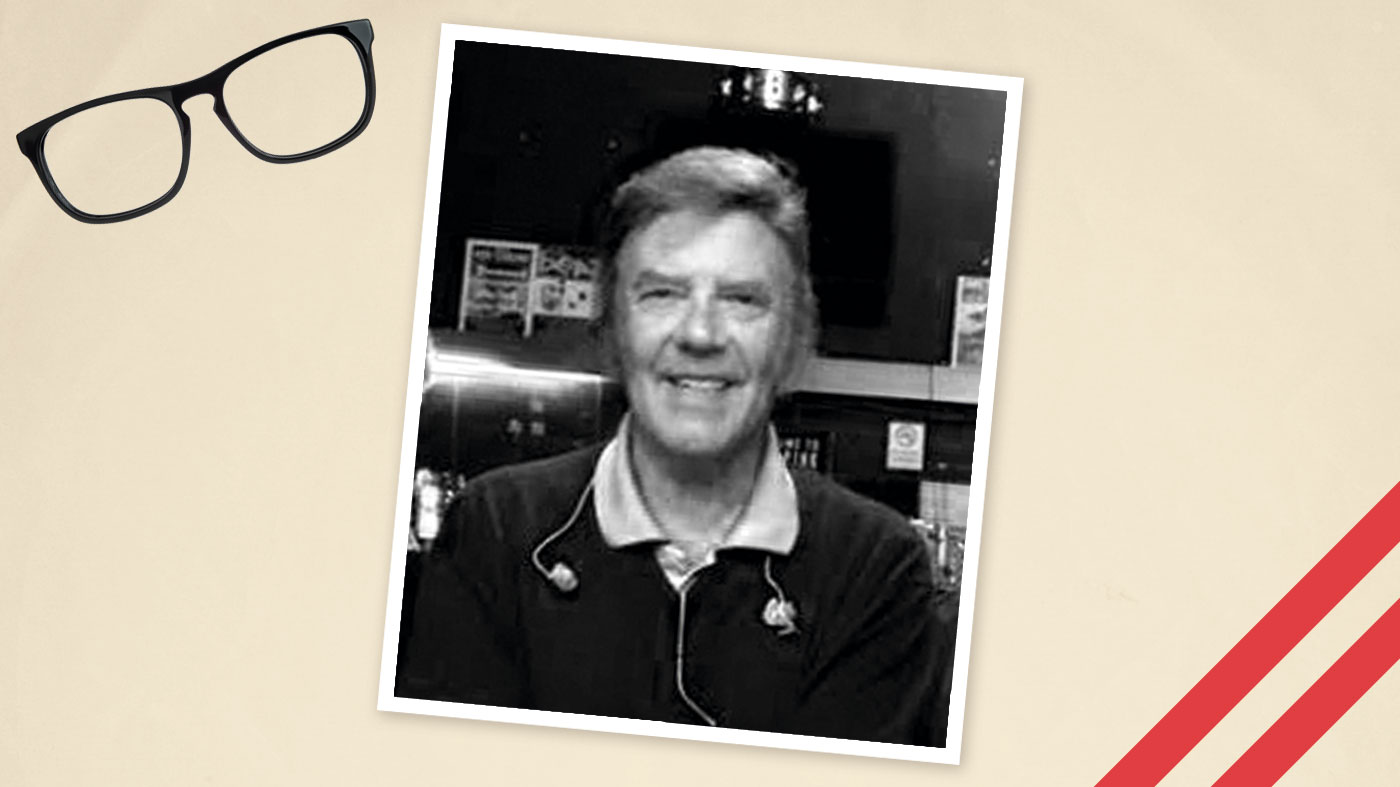

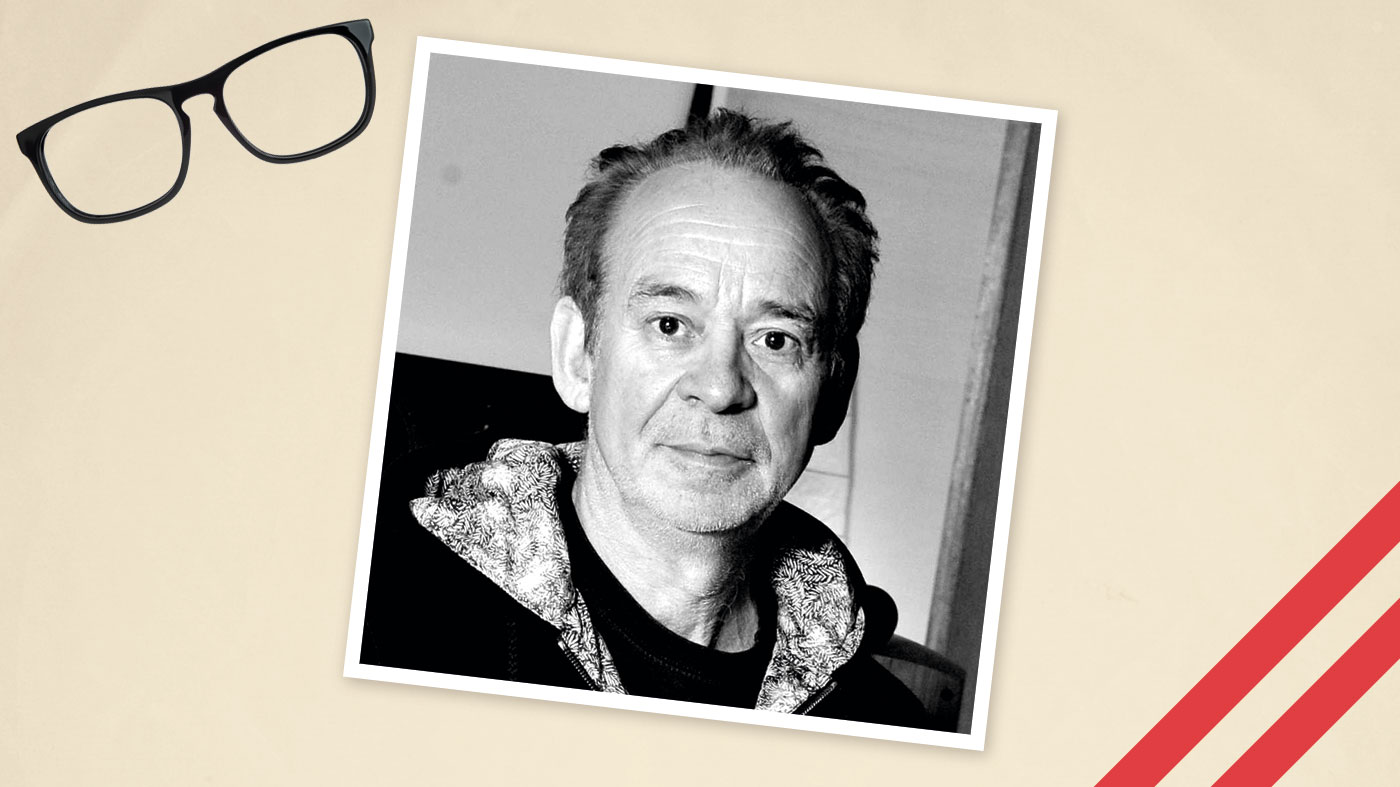

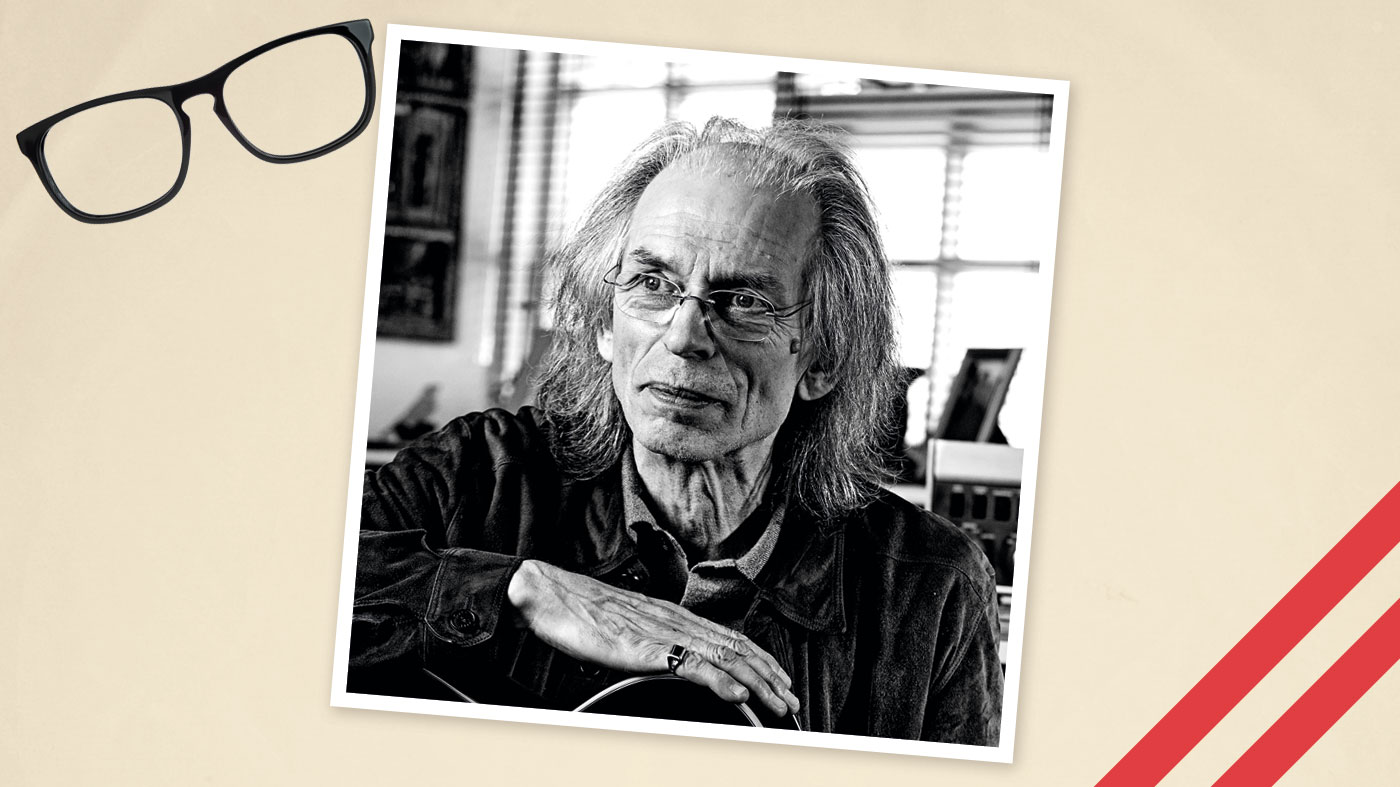

Bill Nelson asks:

Hank, it has been great to be able to ask you, after so many years of being a fan, about a concert you and The Shadows did so many years ago at a cinema in Wakefield in Yorkshire, the town of my birth.

Live, the sound was thrilling. It was a moment that literally changed my life forever

It was a package show with Lord Rockingham’s XI and other acts on the bill in the early 60s. Myself and a school pal were in the early stages of playing guitar. When The Shadows were introduced and the lights went down, the curtains parted in the darkness and the audience could glimpse the glowing lights of the band’s Vox AC30s, set on chrome stands with The Shadows logo in silver on the speaker cloth.

Then a spotlight hit you as the band erupted into Shazam, you all sporting midnight blue mohair suits and red Fenders. The sound was thrilling. It was a moment that literally changed my life forever. I can’t begin to describe how amazing it sounded.

But after all these years, thinking about Shazam, I wonder how much impact Duane Eddy’s music had on yours at the time, despite the differences in style. Were you a fan of Duane’s?

Hank replies:

What I really liked was that beautiful rich sound Duane Eddy got from that tremolo

Hi Bill. Thank you! Yes, I was a fan of Duane Eddy’s. His early records had a wonderful sound. Rebel Rouser - brilliant! Shazam - great piece of music that worked perfectly for us as a guitar band. And a very nice guy, too; I had the pleasure of doing a track with him on an album I did in 1991.

We did a version of Pipeline together: he did the low parts and I did the high bits. What I really liked was that beautiful rich sound he got from that tremolo on the amp - very moody and full of character. So yes, I was a fan of Duane’s, very much so, but I wouldn’t I ever consciously have tried to copy him.

Andy Powell, Wishbone Ash asks:

Did you use tapewound strings in the very early days? Your sound had twang, but there was also a ‘plunk’ to it.

Also, did you use reverb for live performances as well as echo? How about in the studio?

Hank replies:

The reason that the guitar would have a bit of a ‘plunk’ is because the strings were a bit dead

Hi Andy. I never used tapewound strings - hated the sound of them. The reason that the guitar would have a bit of a ‘plunk’ is because the strings were a bit dead. When we were young struggling musicians, you only changed a string when it broke so the strings would be on for quite a while so they lost that brightness and we’d end up with a slightly deader sound.

Hey! Maybe that is part of the secret [laughs]! On stage in the early days, [it was] only the Meazzi echo box, then I went on to a Binson, and then in the 70s the Roland Space Echo. As regards to reverb in the studio, I have an idea that they didn’t put reverb on my guitar because the echo was so prominent.

Phil Manzanera, Roxy Music asks:

Growing up in South America in the late 50s/early 60s, your records were one of the few possible to listen to, they really inspired me.

Was tuning ever a problem? Or do you have perfect pitch, as your playing is always so precise and in tune?

Hank replies:

We hit the tuning fork to get an A, tuned one guitar, then we’d tune it acoustically, one guitar to the other, and the bass to that

Hello Phil. Tuning could be a problem: we didn’t have electronic tuners; you had a tuning fork or you’d to tune to the piano in the venue. We didn’t have a tuning amp, so we tuned up acoustically.

We hit the tuning fork to get an A, tuned one guitar, then if there was a bench in the room we’d lie the guitar down, put the guitar headstock on it to get slightly more volume, and we’d tune it acoustically, one guitar to the other, and the bass to that. Later, we got Vox to make us a small amplifier so at least you could hear your guitar. But still no electronic tuners till much later.

So I appreciate your thought that we sounded in tune. We tried to be, but I always had problems because the whammy bar caused the third string, sometimes the second, to go slightly sharp.

I don’t have that problem in modern times - the way my guitars are set up, I can be pretty vicious with that whammy bar and it will pretty much be in tune. But in those days I was constantly having to adjust particularly the third string at any performance.

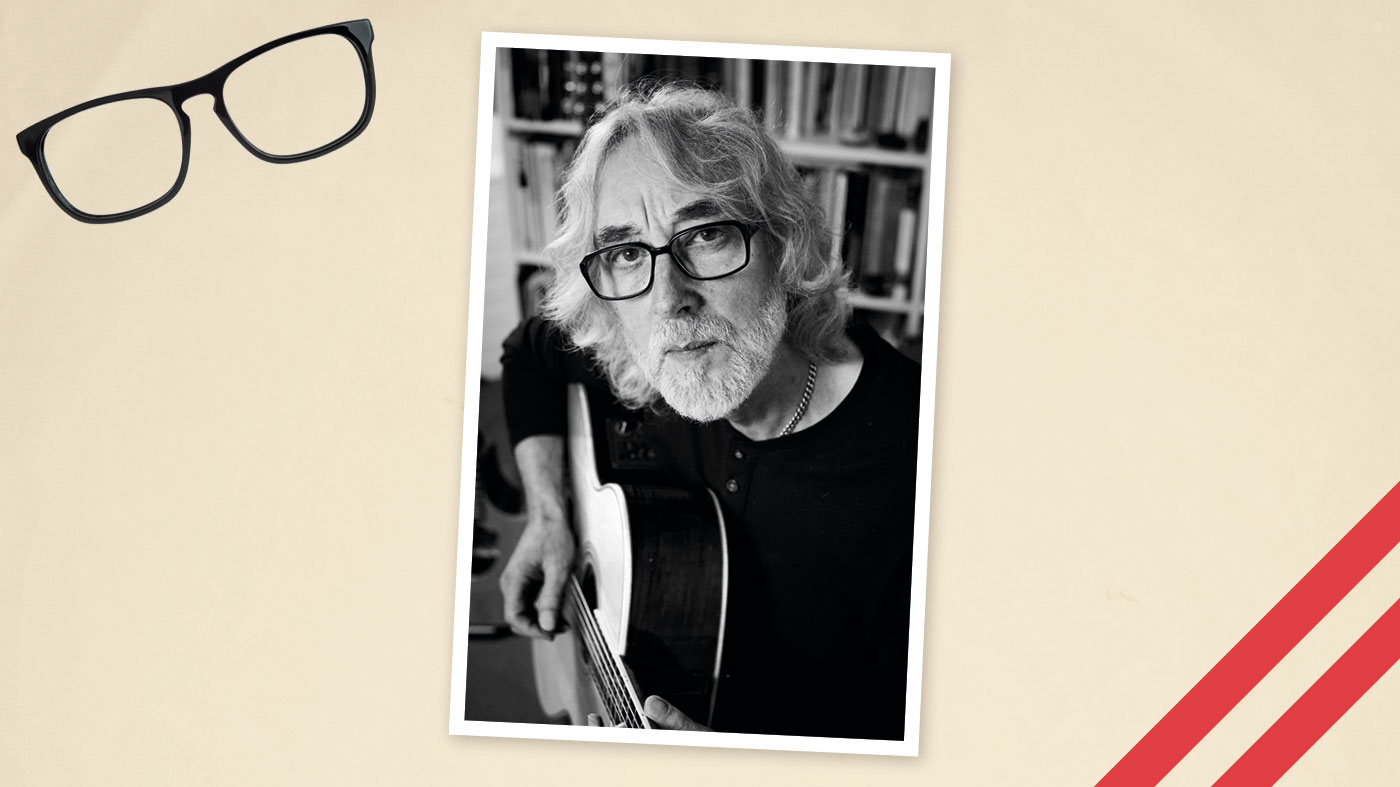

Martin Taylor asks:

I really enjoy your playing with the Gypsy jazz group. How big was Django’s influence in your early days? What did his music mean to you?

Hank replies:

Hi Martin. In the early days I hadn’t heard of Django, but I did have a couple of experiences… One was Bruce and me coming home from a gig that we’d done with our skiffle group in a working man’s club in the Newcastle area.

I said, ‘What is that?’ He said, ‘Django Reinhardt, mate.’ I wasn’t quite sure what that meant

Two guys accosted us and said, ‘Oh, what do you guys do, you’ve got guitars?’ ‘We’re in a skiffle group.’ He said, ‘Can I have a look at your guitar?’ So he picked it up and he played a couple of things. I thought, ‘That’s pretty good.’ I said, ‘What is that?’ He said, ‘Django Reinhardt, mate.’ I wasn’t quite sure what that meant. So I asked around a bit: ‘Does anyone know what Django Reinhardt means?’ Someone said, ‘Yes, he’s a guitarist.’

So I bought a Django LP and it sounded awful. It was so thin, there was no bottom-end, it was just like playing through a little tube or something. I later learned that the very early sessions that Django and Stéphane [Grappelli] did, the materials the record company used were recycled, which apparently made things sound pretty grim. I wasn’t that impressed.

Then years later I heard the Rosenberg Trio and I thought, ‘Wow, that is fantastic.’ So I started to revisit Django and I now have everything he ever recorded. There are some tracks where the vibrato is just sensational, and the way he bends notes and the feel and the runs.

The guy has been a huge influence on so many people. But thinking about it, in some of the early stuff, like Please Don’t Tease where I did a little bit of sweeping, and then I did octaves at the end of Apache, maybe you listen to something and don’t realise you’ve retained the way to phrase something. So it could have had more effect on me than I realise, listening to that dodgy Django thing. But now I’m a huge fan - way ahead of his time.

Darrell Higham asks:

On the first three Cliff 45s, they use session musicians. Ernie Shear played lead guitar, but I’m pretty sure you were playing the live gigs with Cliff at that time.

Who made the decision to have Cliff’s live band back him on his records instead of the session guys?

Hank replies:

Hi Darrel. It was a combination of Cliff and Norrie. Cliff had recorded some sides before we met him - Move It, Schoolboy Crush then High Class Baby. We met up with Cliff at the end of September ’58, just a few weeks after Move It was released. We did his first tour, then they released High Class Baby.

Cliff came up to me surreptitiously and said, ‘Hank, I think I sang better on your version than on Ernie’s’

Cliff had some more recording sessions coming up for Livin’ Lovin’ Doll, Never Mind and Mean Streak. Cliff said to Norrie, ‘I want my band to play on the records.’ Norrie was apprehensive, we were very young and inexperienced and obviously he wants to make good records and to a budget.

So he compromised with Cliff. Norrie said, ‘We’ll do a version with Ernie playing and a version with Hank.’ And on Livin’ Lovin’ Doll I did a lot of string bending - bizarrely on my Antoria, which had this banana-shaped action.

Cliff came up to me surreptitiously and said, ‘Hank, I think I sang better on your version than on Ernie’s.’ So we had a listen and Norrie was happy, so we were on the third single, Livin’ Lovin’ Doll, then Never Mind, Mean Streak and after that Norrie was happy just to use us. We got £7.10s session fee!

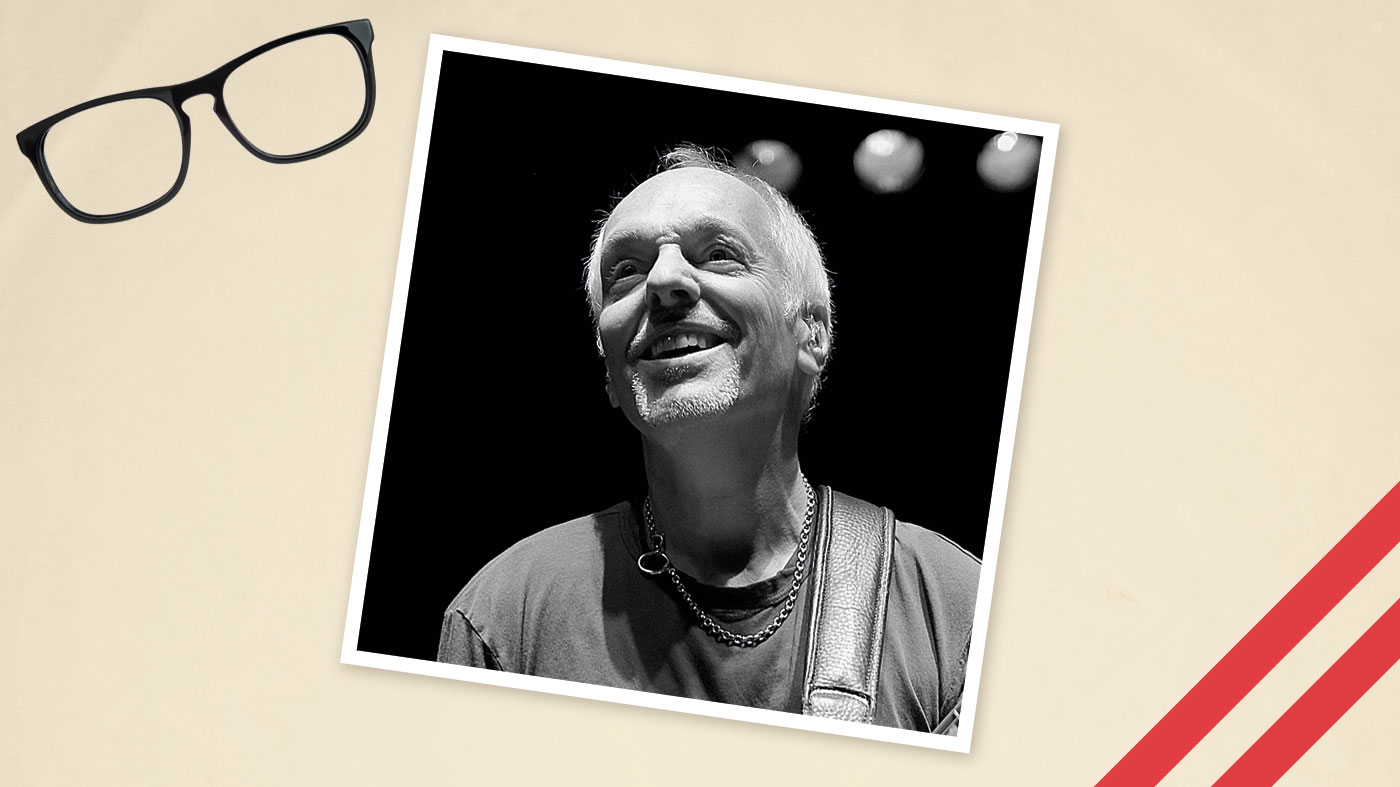

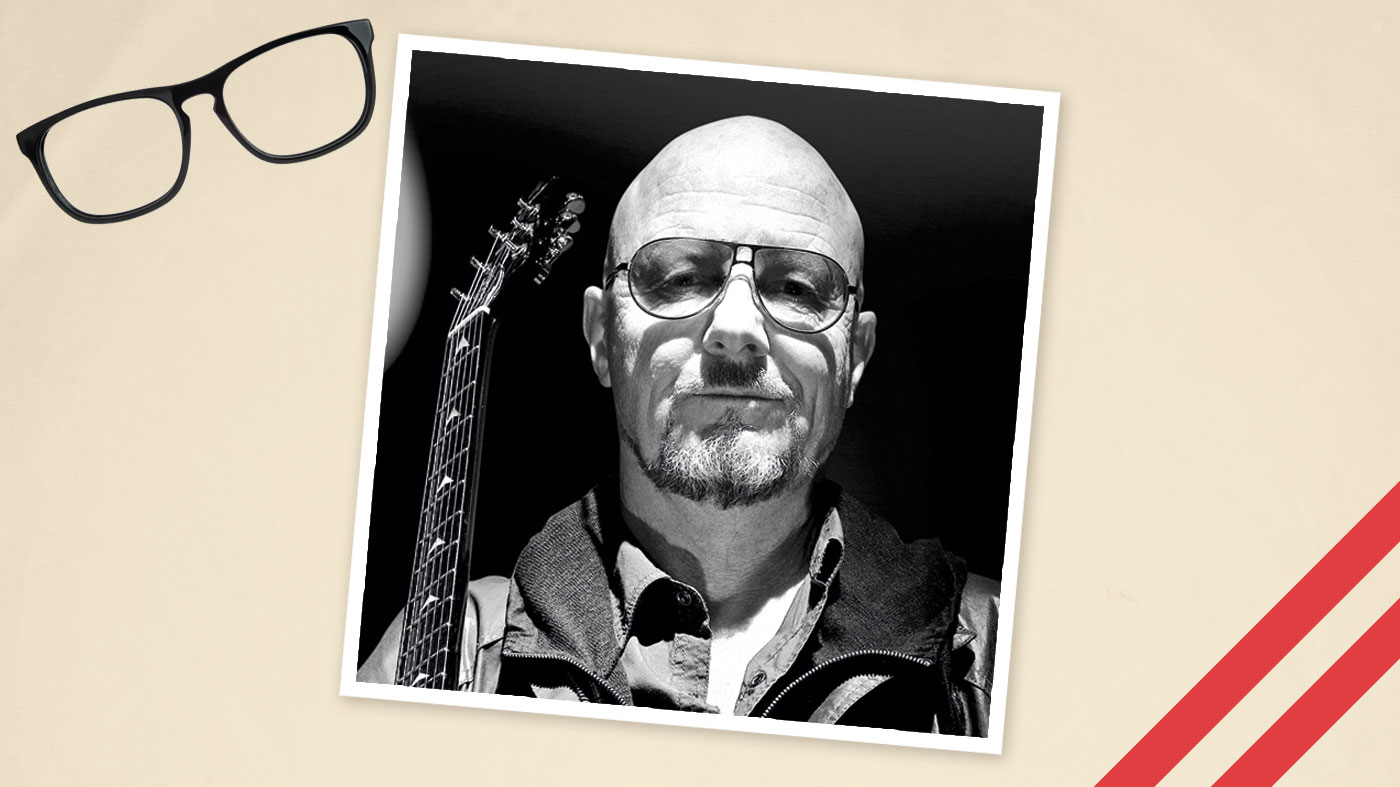

Steve Hackett asks:

I loved hearing your guitar as I was growing up. Which guitarists did you enjoy when you were starting out?

Hank replies:

Guys like Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy were the first guys I really heard playing guitar

Hello Steve. Guys like Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy were the first guys I really heard playing guitar. Then one guy who impressed me was Denny Wright, who played with Lonnie Donegan. I wouldn’t say he influenced me, because he was playing a jazzy style with Lonnie.

Then I started hearing Elvis Presley records, like Heartbreak Hotel and that first LP with Mystery Train and all those things with Scotty Moore; Cliff Gallup playing on things like Be Bop A Lula; Buddy Holly on the Crickets’ stuff; James Burton on Ricky Nelson’s records.

The early Chuck Berry stuff was cool. They were the guys that I really got excited by; it wasn’t jazz, it wasn’t dance music - it had a twangy sound. Sometimes they were bending strings and I thought, ‘Wow, I want to play like that.’ I tried to copy their solos, not always very well, but at least it gave me a bit of a grounding in that style. They were the guys that strongly inspired me.

Steve Lukather asks:

First off, I love your playing and your style is one of a kind.

My question is: when you’re hungry, do you ever walk into catering at the gig and say, ‘I’m a little ‘me’ ’ (as in the Cockney rhyming slang - Hank Marvin: starvin’)?

Hank replies:

Hi Steve! That is very funny. My answer to that is, now that you have mentioned it, I just might!

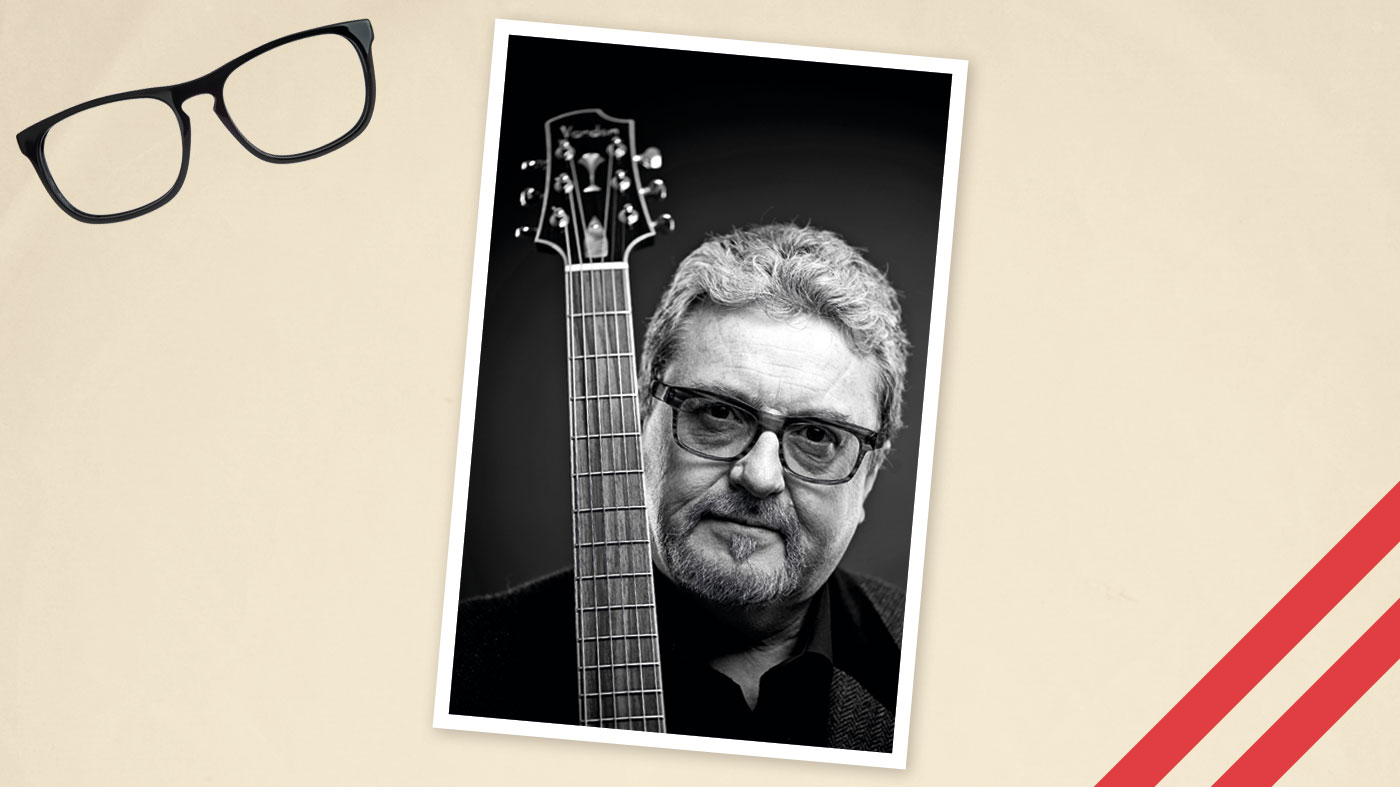

Carl Verheyen, Supertramp asks:

Hank, you have one of the most iconic Strat sounds of all time.

In your early days of playing the Stratocaster, did you do much tweaking or adjusting of pickup heights, spring tension, tone knob to pickup delegation, or did you just take it out of the case and play it as is?

Hank replies:

I basically took my first Stratocaster out of the case, plugged into an amp, played it and was horrified at how heavy the strings were

Hello Carl. Excellent question! In the first instance, none of us knew anything about guitars as regards setting them up. So I basically took my first Stratocaster out of the case, plugged into an amp, played it and was horrified at how heavy the strings were. They felt much heavier than the strings on the Antoria. They came in with 13 to 56 and, oh man, they felt ridiculously heavy.

The action wasn’t that good either, it was a little high, but being a man I pursued it, I carried on, endured. And pickups? No, again, I left them where they were. I think we all thought, ‘Well, they’ve been set up at the factory.’ Later on I became more aware of things such as adjusting pickup height. Tweaks with the wiring? Not until modern times, where I put a switch in to get the bridge and neck pickup on. And I didn’t even know about lodging the switch in between the two.

The only fiddling I did was when I found out that one of my strings was buzzing, I used to take a little bit of the string packet, fold if over a few times, cut it into a small bit, and put it in the nut slot to raise the string. That might be another reason why my string sounded like a ‘plunk’!

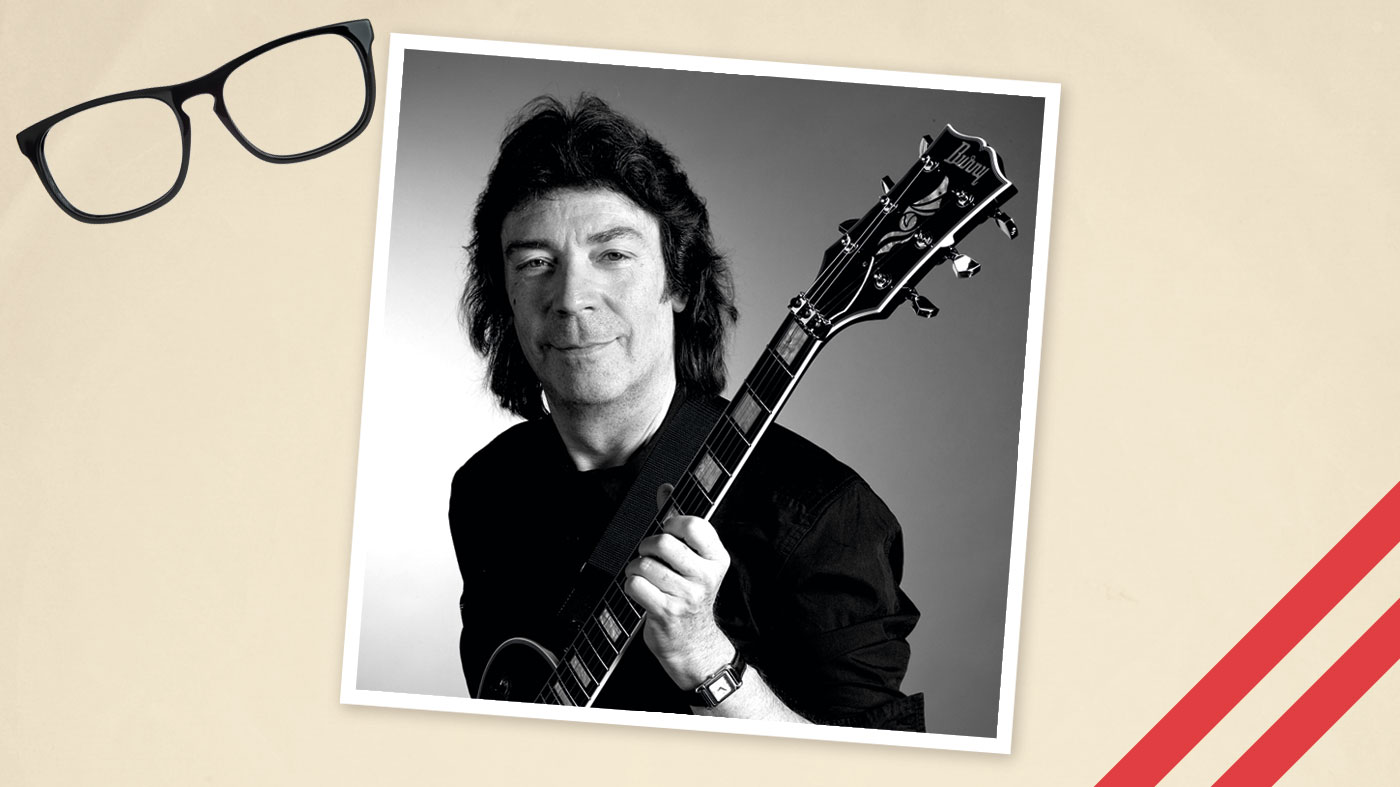

Steve Howe, Yes asks:

During the transition from the Strat to the Burns, did you think the sound was as good?

Was the guitar set up to imitate the sound of the Fender or did you develop an ear for its own qualities?

Hank replies:

Hi Steve. The sound of the Burns was a little different but close to the Strat. They had a good sound. Although I expected some subtle change I didn’t really want it to be dramatic, so Jim Burns and his team endeavoured to get the sound as close as they could to a Strat given the different pickups [Rez-o-matic] and bridge construction.

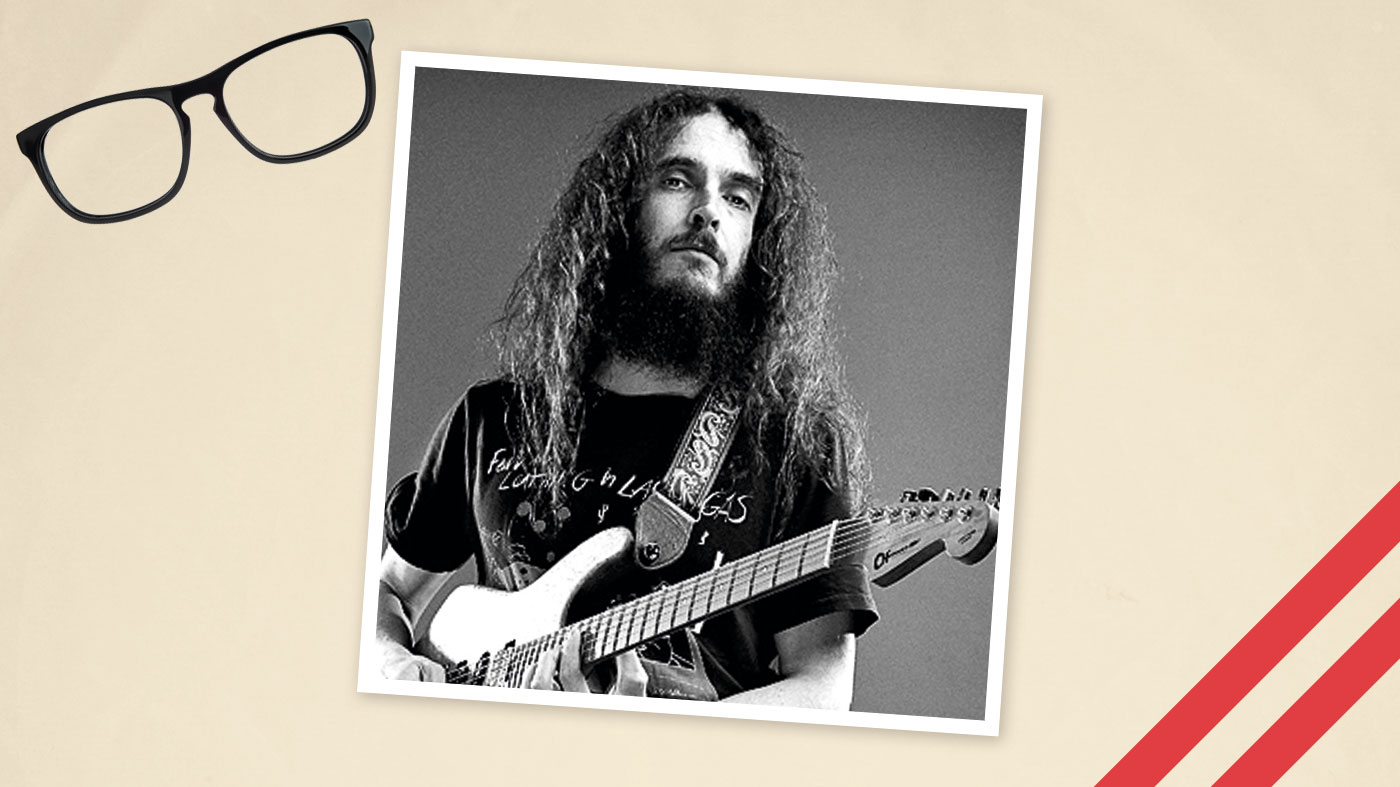

Guthrie Govan asks:

The guitar instrumental was a relatively young art form when you recorded tracks like Apache.

Who or what were your main musical reference points when you started to record tracks in which the guitar carried the main melody? Were you conscious of being an innovator, or was your motivation more of a desire to refine or perfect an existing genre?

Also, your work has inspired countless players. When you hear someone like Jeff Beck, do you recognise elements of your own voice in his playing?

Hank replies:

The human voice and saxes usually had a vibrato that I emulated on the Strat, helping the notes to be more expressive

Hi Guthrie. My reference points were the human voice, various jazz sax ballads with a strong melodic content and, of course, guitarists like Les Paul whom I heard on the radio before I even started playing.

The human voice and saxes usually had a vibrato that I emulated on the Strat, helping the notes to be more expressive. I wasn’t aware of being an innovator. My sound and style more or less happened by accident; the combination of the Strat, the AC15 amp, which soon became the AC30, and the echo box sort of pushed me in a direction, and who was I to argue?

Jeff Beck is one of my favourite electric guitarists. He has wonderful feel and expression, but I don’t know that I hear any of the elements of my musical voice in Jeff’s playing. If there are, he’s taken it to a different level. Some of the next generation of guitarists probably thought, ‘If Hank can get away with it, so can I.’

John Jorgenson asks:

Knowing well your passion for Gypsy jazz, I’ve got a two-part question for you.

What have been the most enjoyable parts and the most challenging aspects of delving in the world of Gypsy jazz, and how has your gift for melodic phrasing on electric guitar helped your playing Gypsy jazz on acoustic guitar?

Hank replies:

Improvising over the Gypsy jazz chord changes was a big challenge; I still have a great deal of room for improvement, but I love it

Hi John. Being blown away by the artistry of Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli was enjoyable and inspiring, as was learning some of the tunes they played with the Hot Club.

Then came the challenge of trying to incorporate the Gypsy picking technique - very different from the technique most of us use, and now I use way more downstroking when I’m playing Gypsy jazz than I ever used to. It’s a sort of semi Gypsy picking technique, but I will carry on regardless.

Improvising over the chord changes was a big challenge; I still have a great deal of room for improvement, but I love it. I do seem to incline toward melodic improvisation, probably because I haven’t got the blinding speed that some like yourself have.

I think, too, that a feel for melodic phrasing is naturally a help in playing the heads in Gypsy jazz tunes. I love your playing, John. I still remember that gig at the Samois jazz festival you played with your Gypsy jazz group. Outstanding, stole the show, and your version of Man Of Mystery still leaves me in a daze. Brilliant!

Phil Hilborne asks:

Do you find the transition between your Shadows-style work and Gypsy jazz difficult? Also, do you see any common threads between the two styles?

Hank replies:

Common threads between Gypsy jazz and rock 'n' roll? Six strings and a pick!

Hi Phil. There was and is a difficulty in transitioning from the Strat to a Gypsy acoustic guitar (with a longer scale), playing what is usually swing jazz music that calls for improvisation.

Playing the acoustic demands a different right-hand technique: you can’t rest your wrist on the bridge unless damping, so the wrist is well arched away from the bridge. Rest stroking and lots of downstrokes are necessary and do produce more volume.

All of the above clearly presents challenges, not the least is trying to play flowing, coherent improvisations that contain Gypsy jazz characteristics such as octaves, trills, ornamentation, injections of chord stabs and so on. Common threads? Six strings and a pick!

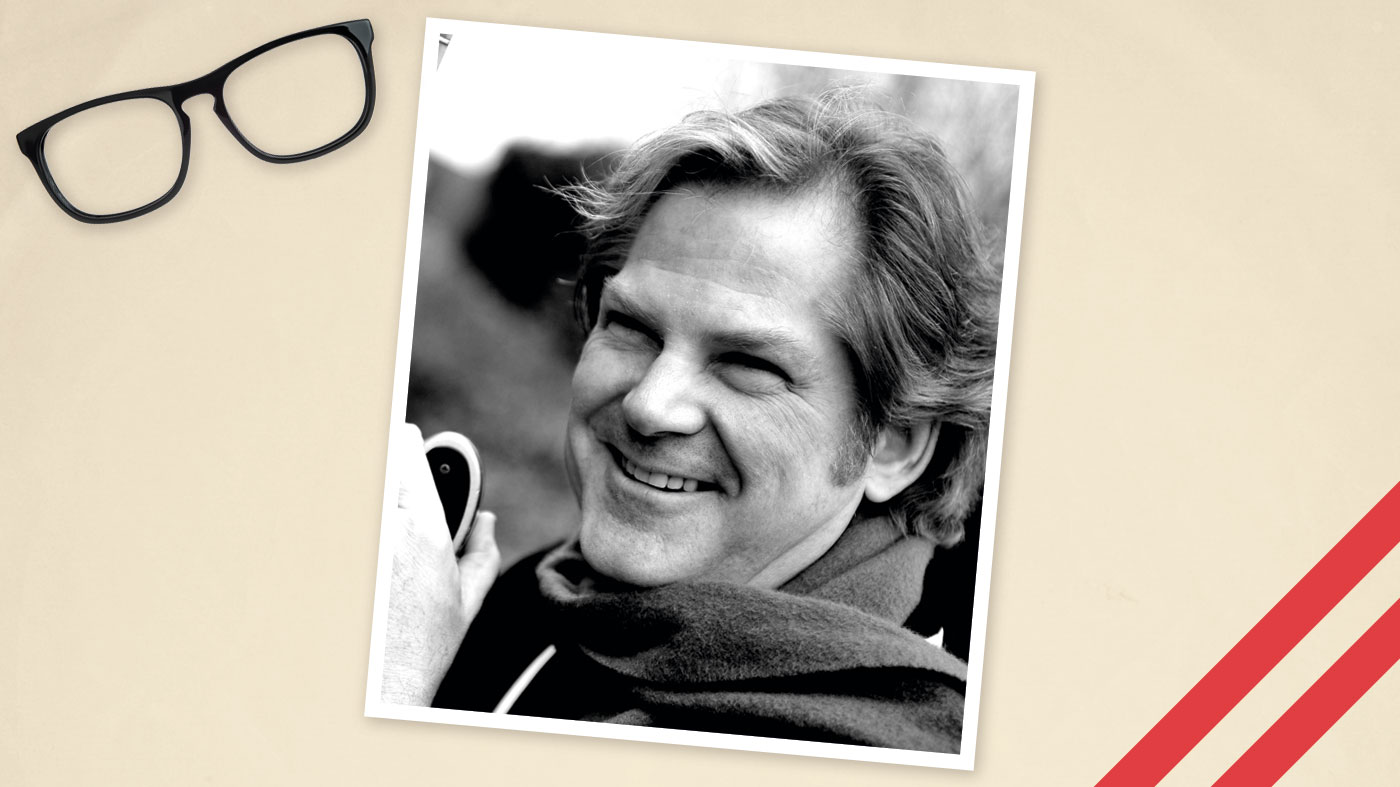

Dave Davies asks:

I was a big fan of your work, but who did you listen to as a boy?

I also loved your tone, your swagger and your stage persona. I liked your glasses like Buddy Holly!

Hank replies:

Lonnie Donegan came on the scene and I got right into skiffle

Hi Dave. Thanks for your kind comments. I still have some of The Kinks recordings on vinyl. In fact, I did an instrumental version of Waterloo Sunset on my last CD [Hank].

I saw Big Bill Broonzy perform at the City Hall Newcastle, and Leadbelly, then Lonnie Donegan came on the scene and I got right into skiffle. After that, I heard Scotty Moore, Cliff Gallup with Gene Vincent, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry and James Burton.

The way they played and the sound they produced was so excitingly different from anything we’d heard in the UK. I wanted to try to play like them, but, as you know, I failed.

Gordon Giltrap asks:

Do you still play the Dave Hodson Selmer copy he made for you?

Hank replies:

I try to give all my Gypsy guitars a loving hug once in a while

Hi Gordon. Actually, I had three, but one was stolen! He made me an experimental copy with a shorter scale, same as a Strat. I still have that, but it doesn’t sound as good as the other two.

Recently, I’ve been using a 60s Favino and a Stefan Hahl: good tone and quite loud. Guitar Man had an original composition on it entitled Song For David. Gary Taylor and I wrote that after David Hodson’s untimely death.

We used the two Hodsons; it had a vaguely Gypsy Latin feel. That was before the theft. I pick it up and play it now and again. I try to give all my Gypsy guitars a loving hug once in a while.

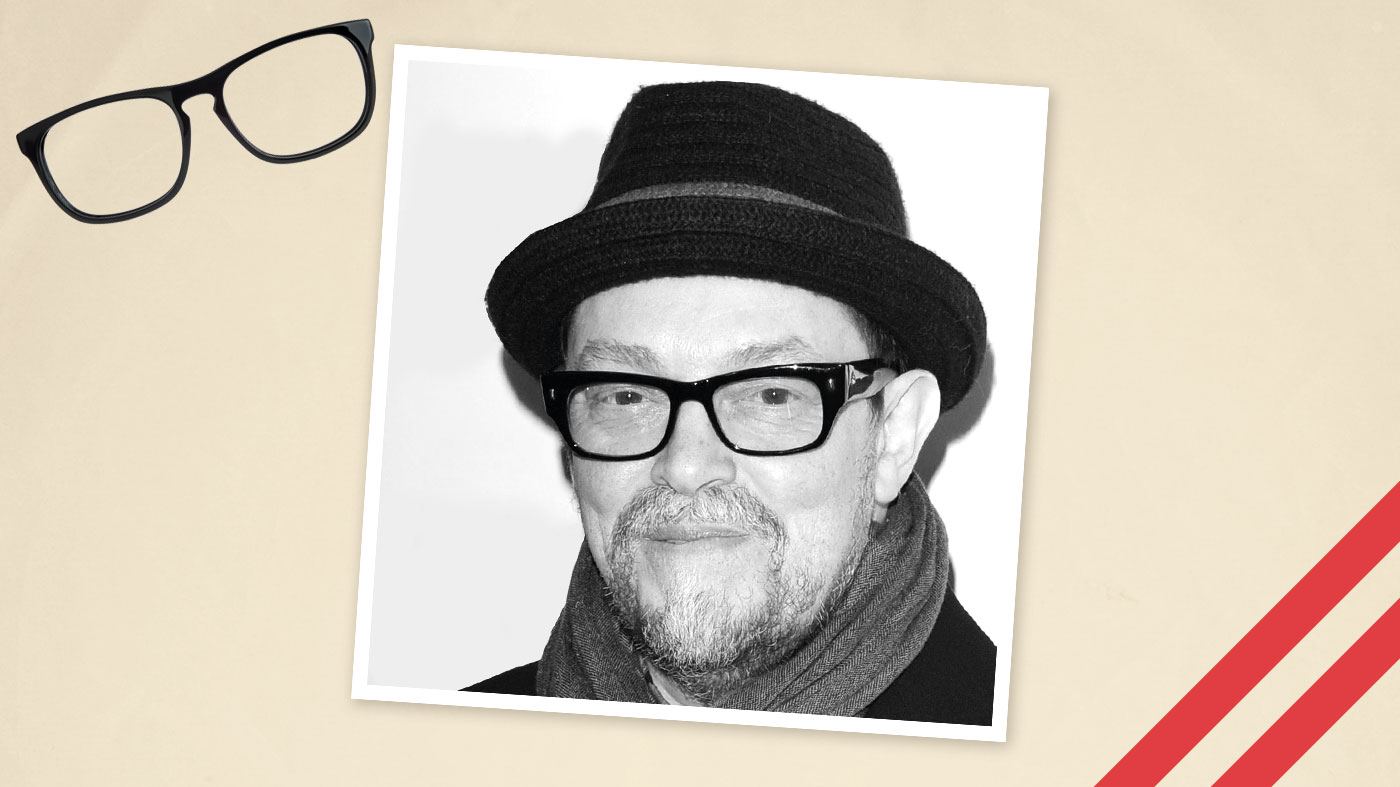

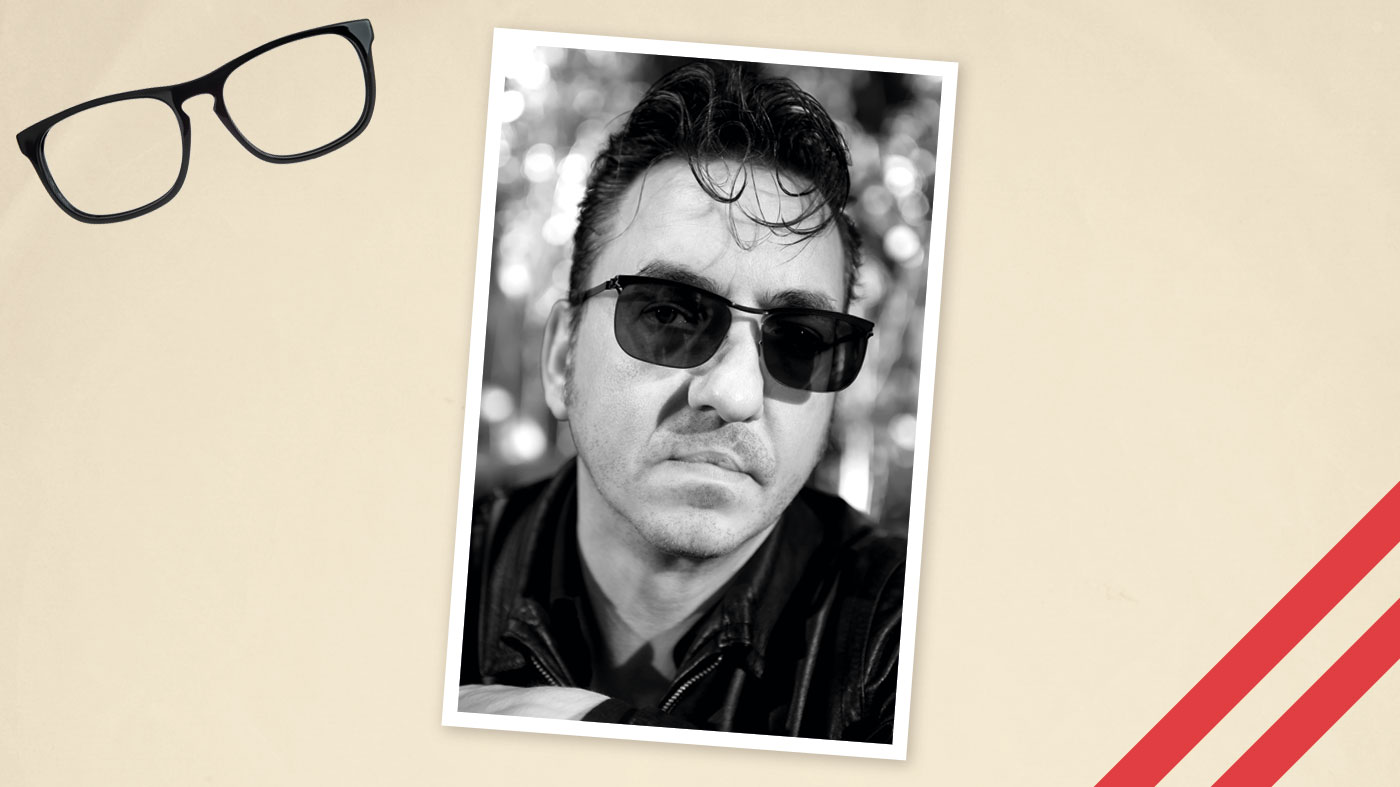

Richard Hawley asks:

One of my favourite tracks of yours is Scotch On The Socks.

How did you come to use the DeArmond pedal on that song and why you think it disappeared from being more widely used?

Hank replies:

Hello Richard. Scotch On The Socks was the result of a bit of fun one night at Abbey Road Studios. I got a grungy sound on my guitar and used the DeArmond pedal to simulate a trumpet ‘Derby hat mute’, wah-wah effect. It was a tone and volume pedal: swivel the pedal horizontally to the left, full bass; to the right, full top.

Add to that the vertical up and down movement to alter the volume and a crying sound could be produced (me when I got it wrong!). But it caused a considerable volume loss and the gear wheels were a kind of plastic and could come unseated.

Reliability was a problem, so I suspect all of the above is why they fell out of favour. I moved onto Morley and Boss volume pedals, which are much more robust - the only thing missing is the DeArmond’s tone shift.

“I’d like to extend my thank you to all the fab guitarists who took the time to pose their questions” - Hank Marvin