14 tips to master the art of wavetable synthesis

Get your head around one of the most powerful sound design techniques available to the modern producer

Yesterday, we invited you into the weird and wonderful world of wavetable synthesis, one of the most powerful and versatile sound design techniques available to the modern producer. Below, we share 14 essential tips for anyone trying to master the art of the wavetable.

1. Wavetables as multi-samples

The ability of advanced samplers to load and work with wavetables presents new options for working with multi-samples too. Let’s say you want to sample the pulse wave oscillator of a classic synth.

With a traditional sampling workflow you may choose to create multiple sample layers, one for each pulse width that you sample, and crossfade between these to mimic pulse width modulation. The same source samples combined into a wavetable are both easier to manage within the sampler, and result in a smoother, more convincing emulation of the original synth.

2. Multiple cycles per frame

There are circumstances where we may want to include more than a single waveform cycle within a wavetable frame. This may be because the sound source cannot produce notes that are within range of the target wavetable frequency, or where a collection of related waveforms include sounds that should be one or more octaves lower or higher than its counterparts, such as with a synth’s sub-oscillator.

In such cases it’s OK to include more than one waveform cycle per wavetable frame; simply double the number of cycles for each octave you go above the wavetable’s nearest note.

3. Marvellous macros

There are many synth parameters that you may wish to automate to create shifting timbres for use in a wavetable. Managing all of the resulting automation lanes and curves can be a pain, though.

Instead use a synth that has macro controllers; assign the parameters you wish to automate to a macro, with appropriate range settings. You then need only automate this single macro controller. Better still, the macro’s automation lane and curve can be reused to create other wavetables.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

4. Destructive processing in DAWs

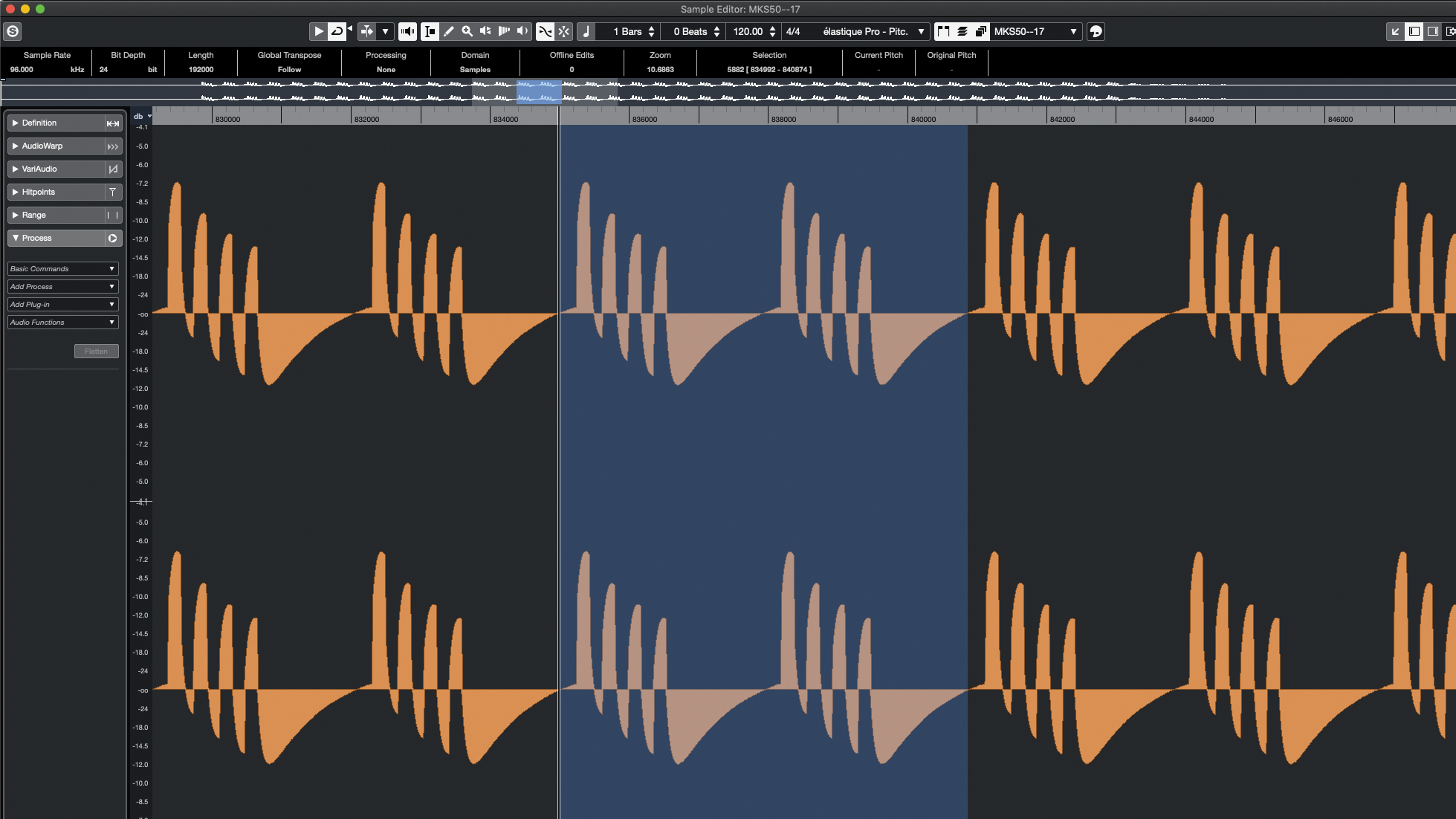

When it comes to processes that directly manipulate the underlying audio recording – time stretching, DC offset removal, etc – most DAWs will create a new copy of the original audio file and apply the processing to this copy.

Be aware that some DAWs will also apply auto fade-up and fade-downs to the new file, meaning if you process just a single waveform cycle, the auto fades will significantly modify that waveform’s shape. Avoid this by processing a longer waveform recording before extracting a single cycle that’s unaffected by any auto fades.

5. Overdrive, distortion and waveshaping

Automating synth parameters is a great way to create waveforms for your wavetables, but don’t forget your DAW’s other capabilities: plugin effects.

Any effect that modifies timbral content is fair game – distortions, saturators, waveshapers, and other processors that like to smash up a sound (although be careful not to use an effect that changes a sound’s pitch). You could apply these effects to a steady unchanging source sound or, if using a synth, you could also automate the source to create some huge timbral variations.

6. It's all just noise

Often, the most interesting wavetables to synthesise with are those that include a very wide range of timbral variation. The point-to-point design approach to wavetable design strongly lends itself to creating this sort of wavetable. The trick is to include increasingly intense, dirty and/or noisy waveforms in the final 10-20% of your wavetable – the final waveform can be little more than noise if you wish.

7. Natural decay

Many acoustic instruments produce timbrally complex decay phases – think of the way a held piano note changes as it decays, for example. We often emulate this in samplers by employing filters and envelopes to mimic the decay, but a wavetable can give far more natural results.

Lift single-cycle waveforms at regular intervals from within the decay portion of the source sample and assemble these into a wavetable. Then, in the sampler, use an envelope to shift the wavetable position to produce a natural instrument decay. The more waveforms you include, the more realistic the results will be.

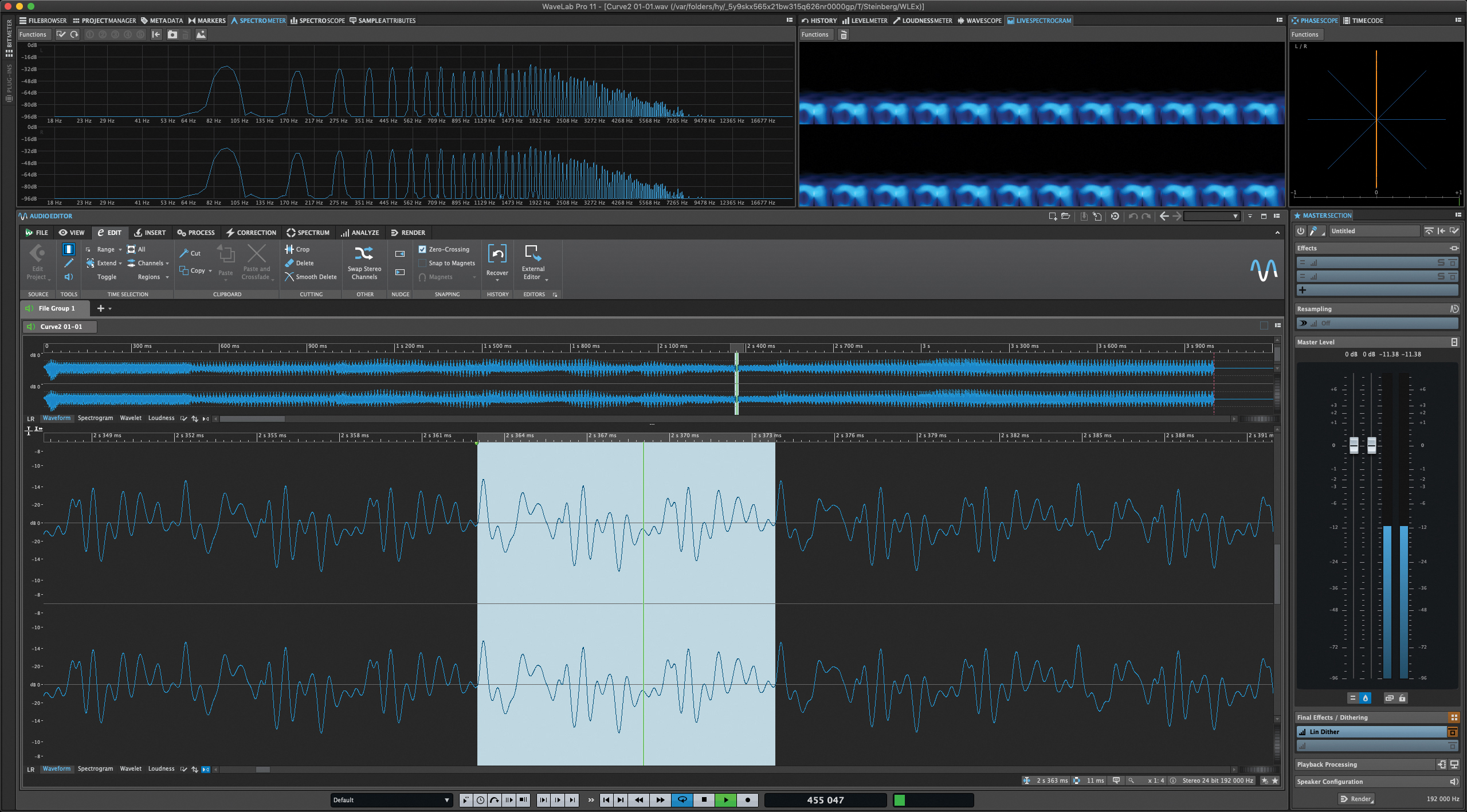

8. Err towards time-stretching

In principle, using tuning to match waveform length to wavetable frame size is preferable to time stretching because it removes a fiddly stage from the wavetable creation process, and avoids any unnecessary processing of the original waveform.

In practice, however, getting the tuning just right is very difficult, even where a synth provides very fine-grained tuning control: the synth’s internal clock may not be 100% accurate, and things like oscillator cross-modulation and filtering can shift the pitch slightly. Conversely, with time stretching, you can measure the recorded waveform and adapt the processing to give perfect results each time.

9. Recreate a classic

We all love a classic analogue synth, but working with such beasts in a modern studio is not the easiest proposition, and is certainly much more of a handful than working with a modern instrument or plugin. A common solution is to use a sampler to capture sounds and patches from the synth, but this can be somewhat inflexible. If you want flexibility, then, record raw and filtered oscillator tones, and build them into wavetables. With careful planning and execution you can capture and recreate the natural nuances and subtlety of the original instrument.

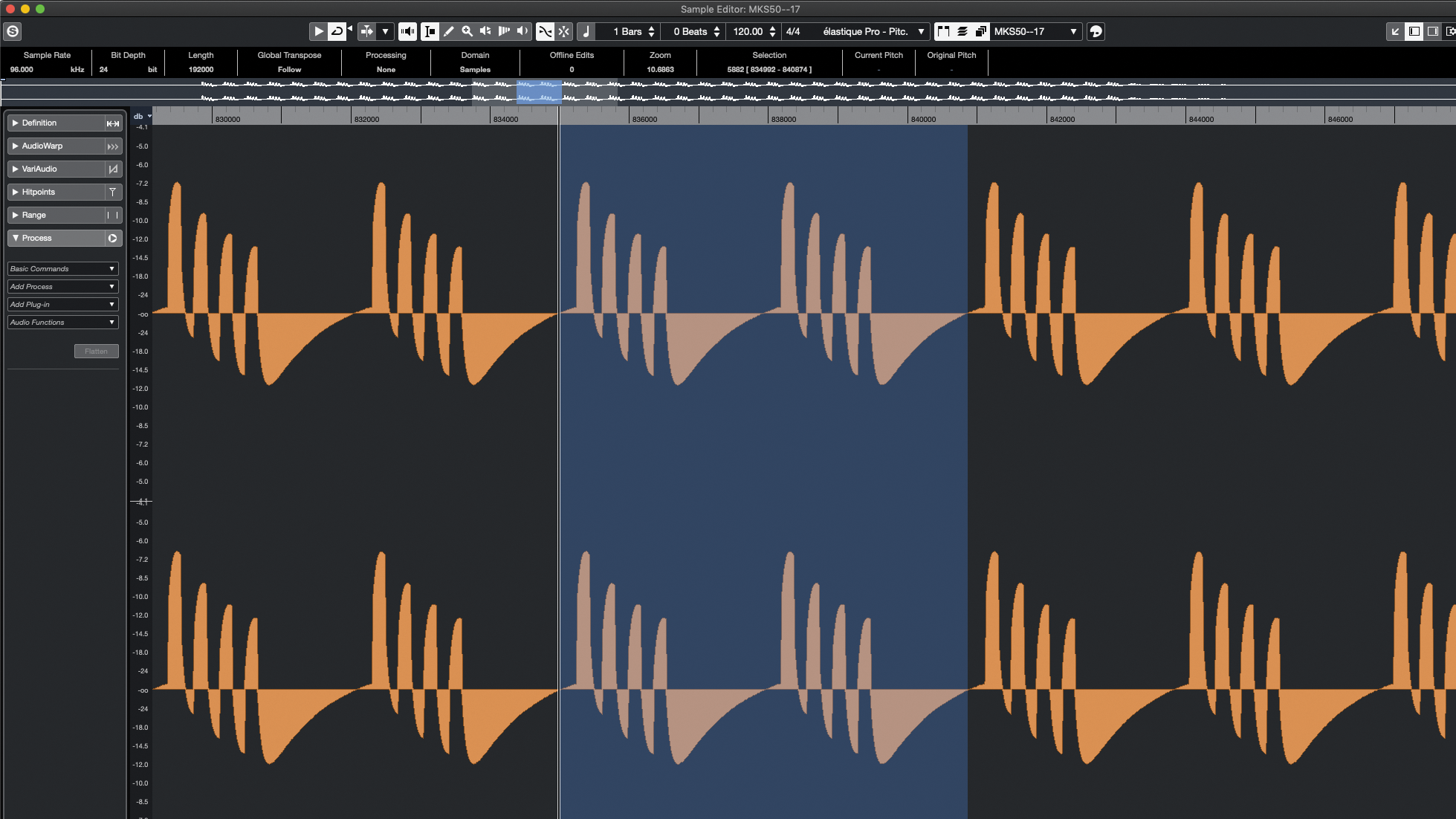

10. Identifying waveforms

Identifying single cycles of a waveform can be quite tricky at times, and when working with an evolving waveform it’s vital that the start and end edit locations you choose are consistent with other waveforms within the recording.

If you’re unsure, calculate the waveform’s single cycle length (in samples), and drag-out selections of this length starting from a zero-crossing point. Then use the number of zero-crossings within the cycle, as well as the number and distribution of peaks and troughs, to help you identify single cycles.

11. Stable waveforms

There are various synth parameters that, when modified, can create a momentary instability in the synth’s output waveform. This isn’t something our ears pick up on, but your recording software certainly does. This can be problematic when using smooth automation curves because the waveform never has a chance to settle down into a steady state – the resulting wavetable will work but may not be what you were aiming for.

For predictable results, then, advance your automation in steps, with each step long enough to allow a consistent waveform to develop, and then extract a stable single cycle waveform from within each step.

12. Be unconventional

There’s no rules that say what sounds can and cannot go into a wavetable, and so there’s no reason to build your wavetable from related evolving waveforms.

Some startling results can be achieved by throwing in waveforms that are markedly different to each other, and relying on the host synth to find a way to morph between them. This works best if the host synth uses spectral morphing as opposed to basic crossfading when traversing between wavetable frames.

13. Wavetable iteration

Random recordings used as wavetables tend to produce harsh timbres, but those timbres can themselves be tamed and tuned using a synth’s filters and EQ (if it has it). One passage through a synth’s innards is unlikely to turn a harsh blarp into a pleasing tone, but it will calm things down.

Create a new wavetable from this calmer source, then rinse and repeat. After a few iterations with some well-chosen filter settings, you can end up with a some very useable and unique-sounding waveforms to synthesise with.

14. Random but not random

The fixed length of a wavetable frame means that repeatedly replaying a frame always produces a pitched note (unless the frame contains pure noise). We can harness this by dropping random recordings into a wavetable synth, but the resulting timbres are usually nasty and only useable in certain ways.

But there are different forms of random – a wash of reverb can have an intrinsic pitch despite its randomness, for example, and so is likely to make far more useable wavetables. Listen for such random-but-not-random sound sources and try them out.

- Read more: The ultimate guide to wavetable synthesis

“A synthesizer that is both easy to use and fun to play whilst maintaining a decent degree of programming depth and flexibility”: PWM Mantis review

“Do you dare to ditch those ‘normal’ beats in favour of hands-on tweaking and extreme sounds? Of course, you do”: Sonicware CyDrums review