"The next generation of Moog products will push boundaries while remaining deeply rooted in the craftsmanship and creativity that defines the brand": Moog at 60, from the ladder filter to the Labyrinth

As the iconic synth-maker enters a new era under inMusic, we speak to several key figures at the company to ask if it can stay true to its roots while embracing the future

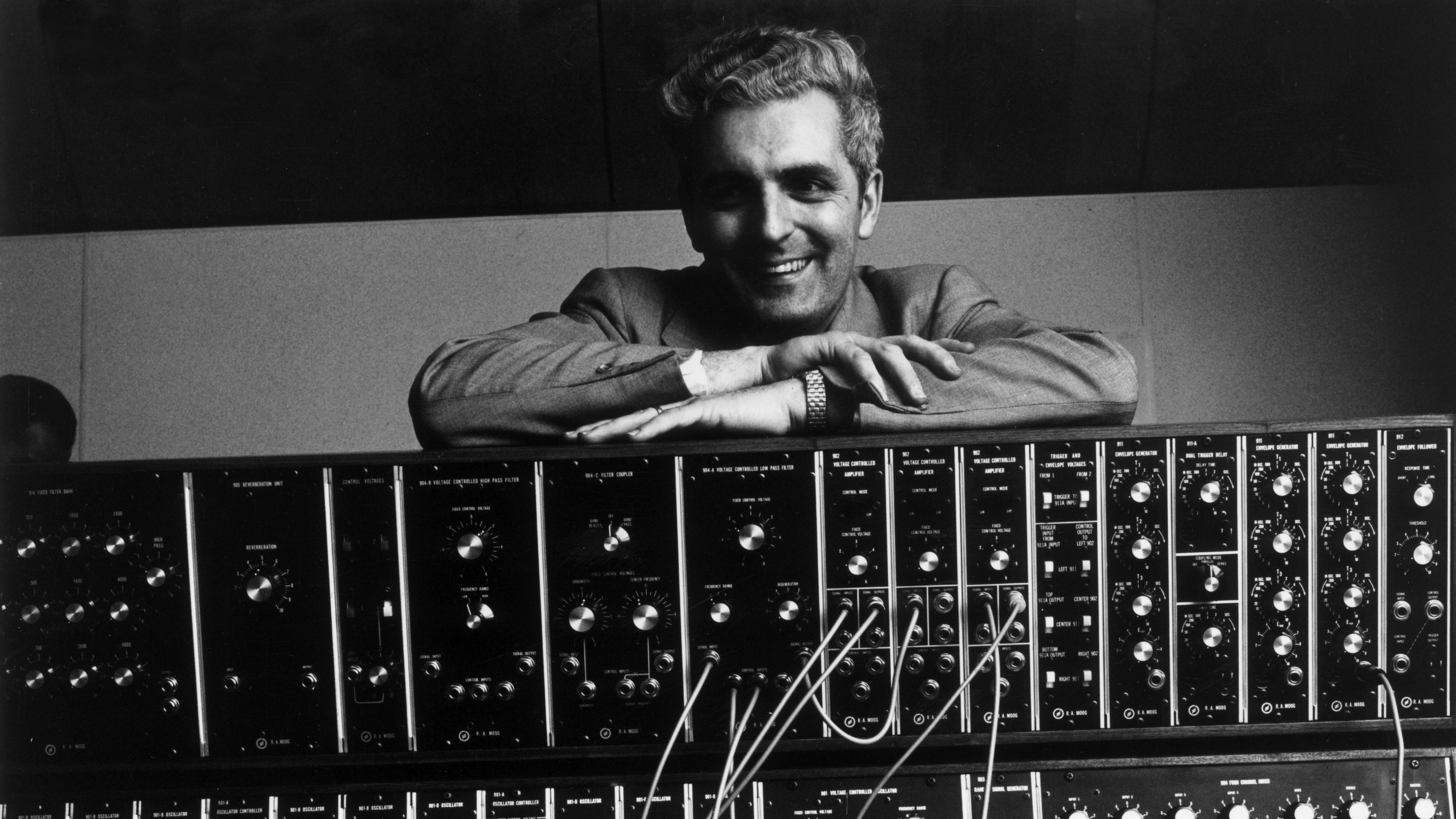

In 1964, Bob Moog didn’t just create a new instrument—he ignited a revolution in music. Working at first from his father’s basement in Queens, New York, Moog created the world’s first voltage-controlled modular synthesizer modules.

He worked closely with experimental composer Herbert Deutsch, and this partnership—a direct collaboration between engineer and musician—would help define how Moog and his company would approach instrument design far into the future. “I’m an engineer,” Moog once said. “I see myself as a toolmaker and the musicians are my customers. They use my tools.”

The Moog modular represented a fundamental shift: its network of voltage-controlled oscillators, filters and amplifiers expanded and redefined the ways in which humans think about and generate sound. Sandwiched chronologically between the development of advanced acoustic instruments and the oncoming emergence of digital music-making, Moog’s analogue circuits allowed for an extraordinary and unprecedented level of control over the shaping of sounds. The Moog ladder filter, which he introduced during this period of creative output, would go on to become one of the most influential and imitated circuit designs in the history of electronic music.

The company's early years were marked by rapid innovation and growing cultural impact. The release of Wendy Carlos's Switched-On Bach in 1968 demonstrated the Moog synthesizer's potential for both technical precision and emotional expression. The groundbreaking album sold over a million copies, and helped legitimize the synthesizer as a serious musical instrument in the eyes of the mainstream music world.

1970 marked another hugely significant moment for Moog, with the introduction of the Minimoog Model D. The instrument took the discreet elements of Moog’s modular system and tailored them into a portable, plug-and-play synthesizer. The Minimoog's influence can’t be overstated: it’s all over countless recordings from the 1970s onward, from progressive rock to funk, jazz, and early electronic music.

Recounting the artists that embraced it effectively becomes a list of those that defined the music and sounds of the era: Stevie Wonder, Keith Emerson, Giorgio Moroder, Kraftwerk, Sun Ra, Pink Floyd, and Herbie Hancock (to name a few) helped bring the Moog sound into the popular consciousness. Wonder, who would become a lifelong Moog enthusiast, once described the synth as "a way to directly express what comes from your mind." It’s a sentiment that captures the transformative power of Moog’s instruments.

The company's history hasn't been without its challenges, however. Musical tastes started to shift later in the 1970s, and increased competition ramped up from other synthesizer manufacturers. The acquisition by Norlin Music in 1973 led to a period of corporate oversight that many viewed as a challenge to the company's creative freedom. Bob himself clearly agreed, leaving the company in 1977 and going on to found Big Briar (which would later be renamed Moog Music) in North Carolina.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The 1980s were a turbulent period for analog synthesis in general, and coincided with Moog’s absence from the company he founded. Digital synthesizers, particularly those from Japanese companies like Yamaha and Roland, began to dominate the market. These instruments offered dramatically different, more high-tech sounds; they were also easier to mass produce, and therefore could be sold for more affordable prices. Under Norlin’s ownership, Moog struggled to compete, and by 1987, the company ceased operations entirely.

Bob remained active in the industry, however, developing instruments through Big Briar, including his own theremin designs, as well as the legendary line of Moogerfooger analog effects pedals. (Moog’s lifelong passion for the theremin began at age 14, when he first discovered it in an issue of Electronics World; he built one based on plans published in the magazine, and five years later he and his father were building and selling theremins out of their home.) Meanwhile, during this period in the 1980s, a growing admiration for Moog’s classic analog synthesizer designs continued to emerge from a dedicated and active community of synthesizer enthusiasts.

This paved the way for a Moog renaissance in the 1990s and early 2000s, as interest in analog synthesizers surged among a new generation of musicians and producers. Now based in Asheville, North Carolina, the company began reissuing classic Moog designs while also developing its own original circuits and instruments. The 2002 Minimoog Voyager, Bob’s modern reimagining of the Model D, demonstrated that there was still a strong interest in (and vigorous market for) high-end analog synthesis—even in what had quickly become the digital age. The Voyager became an instant classic.

The period following Bob Moog's passing in 2005 has seen the company continue to evolve. The introduction of the Mother-32 semi-modular synthesizer in 2015 marked a significant moment, embracing the nascent Eurorack format and offering a more accessible entry point into modular synthesis, while maintaining the company's reputation for quality and innovation.

This was followed by a series of complementary instruments including the venerated DFAM (Drummer From Another Mother) and Subharmonicon, each exploring exciting, idiosyncratic approaches to synthesis and sound design. Subsequent releases like the Grandmother and Matriarch synthesizers successfully merged vintage Moog circuits with modern patchability and features, while maintaining a connection to the company's classic sound.

The Moog Labyrinth, developed just before another existential moment for the storied company, represents one of the clearest examples of how the company has continued to evolve. Among other things, its generative sequencer, sinewave oscillator, morphable low/bandpass filter, and wavefolder all represent clear deviations from the norm for Moog. Max Ravitz, who was deeply involved in the instrument's development, which began in early 2022, explains that it was conceived as a deliberate departure for the company.

“I really wanted to make an instrument that was going to subvert expectations and be a big surprise for most people who are familiar with Moog,” Ravitz explains. “I pay attention to what people are saying in the marketplace, and I just noticed a lot of people when talking about Moog would point out a reiteration of ideas that we'd been using for a while.” This push for innovation manifested in a host of unique features and ideas, including parallel processing paths and a sophisticated wave folder. Moog’s Rick Carl, who was the main engineer on the project, notes that “every part of the signal path on Labyrinth is a new design for Moog.”

The instrument took inspiration from various sources, including West Coast synthesis, a number of Eurorack modules, and vintage percussion synthesizers, all while charting its own course. “This was definitely an attempt to appeal to some younger music producers who are maybe into Elektron gear, or stuff that’s more aimed at techno, house, IDM and these more forward-thinking electronic music genres.” (Lorre Mill’s Double Knot, Music Thing Modular’s Turing Machine, Winter Modular’s Eloquencer and Pearl’s classic Syncussion all get name-checked as inspirations.)

Labyrinth actually started its life as “Davis”, in the same form factor as Moog’s smaller Mavis synthesizer, and was meant to be an adjunct to DFAM that offered alternative approaches to percussion synthesis. But once Carl started actually messing with some designs, the team realized that the concept had more potential than the small footprint could accommodate.

Ravitz says that there were definitely some risk-averse headwinds within the company in getting the idea off the ground; still, the development process reflected a period of creative freedom. It seems safe to say it’s been a success: “It’s definitely paid off, and I think a lot of people are happy and surprised with how it’s landed,” Ravitz says. “But we will see if we keep getting to be this kind of unbridled and weird.”

While the Labyrinth is part of Moog’s semi-modular line—where most of the company’s more experimental designs have lived for the past decade—iterations of some of its ideas were integrated into Muse, which is very much in Moog’s “main line” of instruments. “Some of the generative nature of Labyrinth definitely found its way into Muse, but implemented in quite a different way,” Ravitz notes. “Once we can get the weird concept in, then it’s nice because we can at least get some kind of echo of it happening in later products.” The two expect that this won’t be the end of the line for Moog’s integration of generative sequencing ideas into its instruments.

In June of 2023, a year after development on Labyrinth began, Moog was acquired by inMusic, a conglomerate that owns brands including Akai, Alesis, and Numark. The announcement sent shockwaves through both the music technology industry and the synthesizer community. The subsequent closure of the factory store in Asheville, North Carolina—a destination that had become something of a pilgrimage site for synthesizer enthusiasts—and the layoffs that followed only intensified these reactions.

The acquisition sparked discussions about the future of American manufacturing, the preservation of Moog's unique company culture, and concerns about whether the brand's commitment to innovation would survive under corporate ownership. (It also marked the end of Moog's employee ownership structure, which had been in place since 2015. The company has said that as part of the transition, all past and present employees participating in the Employee Stock Ownership Program received a payout.)

But not all were surprised by the news. In the years leading up to Moog’s acquisition, the synthesizer market had become increasingly competitive, with companies like Behringer aggressively undercutting premium brands by producing affordable analog clones of classic synthesizers, including Moog’s own Minimoog Model D. Behringer’s ability to mass-produce these instruments at a fraction of the cost put significant financial pressure on Moog, which continued to manufacture its products in the U.S. with higher production costs. (Behringer has publicly stated that Moog’s then-CEO Mike Adams reached out to them regarding a potential acquisition; Moog has neither officially confirmed or denied this claim.)

The broader synth market was also shifting toward hybrid and digital technologies, with brands like Arturia and Sequential offering innovative digital-analog hybrid instruments at competitive prices. Moog, known for its premium, hand-crafted analog instruments, found itself struggling to compete in an industry increasingly driven by affordability, accessibility, and technological advancement. Economic factors such as rising material costs, Covid-induced supply chain disruptions, and fluctuating demand further complicated Moog’s position, and economies of scale necessary to survive in the evolving market.

“Definitely we lost a lot of people that Rick and I were close to, and we’re getting used to the changes involved,” Ravitz says, speaking to the human cost of the transition. But he also offers a more nuanced perspective on the current state of things: “For the most part, it has been feeling positive and the good momentum is encouraging us to work on more instruments.”

"Before inMusic acquired us, we would still get PCBs manufactured in China, and then do a lot of mechanical assembly in Asheville"

One of the most contentious aspects of the inMusic acquisition has been the shift in manufacturing practices. It now seems clear that more of the process has indeed been shifted overseas, primarily to Taiwan; Moog does continue to produce instruments in Asheville, NC, but now at a new facility with the “required infrastructure and resources to help it thrive,” according to Richardson.

Engineering and product development will also remain in Asheville, but are moving to a new location in Asheville’s historic Citizen Times building in early 2025. (It’s worth noting that the local newspaper of the same name recently vacated the building’s second floor, which it had been in since 1939, though renting after its parent company Gannett sold the building to local investors in 2018—another sign of the times, to be sure.)

The reality for Moog, however, is likely more complex than the initial narrative of American manufacturing being replaced by overseas production might suggest. “People are talking about the manufacturing that we're doing that occurs in Taiwan and kind of speaking of it negatively,” Ravitz explains. “But to be totally fair, before inMusic acquired us, we would still get PCBs manufactured in China, and then do a lot of mechanical assembly in Asheville.”

This highlights a crucial point often overlooked in discussions about manufacturing; modern electronics production has long been a global endeavor, even for companies strongly associated with domestic manufacturing. “I think that people's perception of what US manufacturing in Asheville means now and what it meant before is a little bit skewed by a lack of understanding of manufacturing,” Ravitz notes. “I would say that our new contract manufacturers that we’re working with in Taiwan seem like a step up from those we were working with in China.”

Carl also reiterates that domestic production hasn't been abandoned entirely: “We're still manufacturing instruments in Asheville. We still have a factory, we still have lines running. None of that has changed. In fact, there's been a little bit of reinvestment in keeping manufacturing there.”

Carl also says the manufacturing changes have even led to certain improvements, both in terms of quality and scale. “The manufacturing, just the scale that we're able to achieve is remarkably improved,” he explains. “And the quality of what we're getting ... the prototype I'm looking at right now, they nailed it on the first try. I’m super optimistic about the future of manufacturing at scale, and our ability to pump stuff out faster because we have all these resources behind us.”

"I’m super optimistic about the future of manufacturing at scale, and our ability to pump stuff out faster because we have all these resources behind us"

This improvement in manufacturing capabilities has been accompanied by enhanced engineering resources. “We've gotten a lot more efficient just from the resources that inMusic afforded us,” Carl notes. While the romantic notion of all-American manufacturing may have shifted, the result of the acquisition on actual quality and capability of Moog's production operation still remains to be seen.

Moog president Joe Richardson emphasizes the acquisition’s ability to improve Moog’s ability to remain agile in a market that demands it. “Without divulging too much, I can share that the strengths of inMusic go far to shore up constraints that challenged Moog Music for many years,” he says.

“inMusic has a well-exercised focus on technology development and the practical application of that technology. Formerly, Moog resource constraints required a choice: leverage existing know-how or develop and integrate modern technologies. The lifted constraints and access to innovative technologies expands the choices our instrument designers and engineers have at their disposal. Moog’s instruments will come from the freedom inMusic provides.”

Richardson reiterates the point that the company’s decision to expand production internationally reflects a desire to achieve lower price points for its products. “As demand for Moog products continues to grow, this shift allows us to deliver the same level of exceptional sound and build quality while ensuring availability across markets,” he says, insisting that the decision was not taken lightly. “We remain deeply committed to honouring Moog’s heritage in Asheville, where the innovation and creative vision behind every product originate. Expanding production has allowed us to focus more heavily on advancing R&D efforts and introducing new product categories, while continuing to deliver the high standards expected of Moog instruments.”

Of course, the same unknowns apply to the company’s willingness to take chances on innovative instruments. It seems clear that the acquisition has brought about significant changes in terms of how products are developed at Moog; what’s less clear is whether these changes are entirely for the worse.

Where once the process involved numerous stakeholders and what Carl describes as “a lot of cooks in the kitchen,” the approach has become more streamlined. The development of the Labyrinth, which occurred just before the acquisition, offers an interesting point of comparison. “The reason that we were able to develop it so quickly, I think, was partially just because Rick and I were allowed to kind of run with it,” Ravitz explains, noting that other projects with more stakeholders, like the Muse, took “a good five or six years.” It’s unclear whether this instance was a relic of the past, or a sign of things to come.

The new, more structured approach certainly has its advocates. “Our engineering group has remained, we've continued to operate the same as we always did,” Carl notes. "We've also improved our process quite a bit. We've gotten a lot more efficient just from the resources that inMusic afforded us.” As Moog moves forward under inMusic's ownership, the challenge remains to balance its storied heritage with the demands of the modern synth market and globalized capitalism.

“Over the next decade, we intend to lead the charge in synthesizer innovation while expanding into new frontiers and enhanced connectivity for music production”

Though Moog appears to be maintaining its commitment to innovation while adapting to new organizational structures, it’s difficult to predict the future. The release of fantastic instruments like the Labyrinth and Muse suggest a company willing to explore new territory. But given that their development was largely finished before the acquisition, one can only guess as to whether those designs would have been greenlit or executed as well had their development been entirely under the supervision of its parent brand.

As Moog looks toward its next 60 years, the company appears to be finding its footing in a new era. While the creative process has become “a little more streamlined” post-acquisition, according to Carl, the company maintains its ability to innovate and push boundaries. The engineering group has remained intact and has even seen improvements in their process. “We've gotten a lot more efficient just from the resources that inMusic afforded us,” Carl explains. This efficiency, combined with improved manufacturing capabilities, suggests a company better positioned to bring new ideas to market quickly.

These changes haven't come without cost—the loss of some long-time employees and changes in internal structure have altered the company's creative dynamic. Where once there were “a lot of cooks in the kitchen” bringing different viewpoints and experiences to the table, the process has become more linear.

"The next generation of Moog products will push boundaries while remaining deeply rooted in the craftsmanship and legendary creativity that defines the brand"

Richardson, however, unsurprisingly remains bullish on the subject. “Over the next decade, we intend to lead the charge in synthesizer innovation while expanding into new frontiers and enhanced connectivity for music production,” he says. “We’re particularly excited about introducing products that cater to both the seasoned artist and the new wave of creators exploring synthesis for the first time. The next generation of Moog products will push boundaries while remaining deeply rooted in the craftsmanship and legendary creativity that defines the brand.”

As Moog celebrates its 60th anniversary, it stands as a company in transition but not in retreat. It certainly seems possible that the spirit of innovation Bob Moog instilled will continue to manifest in new and unexpected ways, even as the company adapts to modern business realities and changing market demands.

The next chapter in Moog's story will likely look different from its past, but the core elements that have made the company a crucial part of electronic music's development—innovation, quality, and a top-tier talent pool to draw from—appear to remain mostly intact. As Moog enters its seventh decade, the question remains: Can a brand so deeply rooted in analog tradition thrive in an increasingly digital world? If the Labyrinth and Muse are any indication, the answer may lie in Moog’s ability to honour its past while exploring new sonic frontiers.

Evan's writing has appeared in a host of print and online publications, including Rolling Stone, Wired, and The Fader. His primary areas of focus have been music technology, visual art, and videogames, and the intersection of the three. He's been using tools from all of these realms since the early 00s, and continues to do so from his worryingly flood-prone shed in Los Angeles.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too

MusicRadar deals of the week: Enjoy a mind-blowing $600 off a full-fat Gibson Les Paul, £500 off Kirk Hammett's Epiphone Greeny, and so much more