"If you're not joining in, you're out… I got my P45”: How the Bee Gees, Burt Bacharach and coke derailed the first attempt at recording Oasis's Definitely Maybe

It started with a promise between friends and turned into every producer’s worst nightmare: Inside the aborted first attempt at recording Oasis’s classic debut

It’s sometime in the late ‘80s and Noel Gallagher, a guitar tech for Madchester psych-pop band the Inspiral Carpets, is in the back of a tour bus, skinning up and chatting with David Batchelor, the band’s sound engineer.

Despite their age difference – Noel is in his early 20s, Batchelor in his 50s – the two men share a love of the same bands, and Noel has a respect for the older man’s past production work.

Right away, it was there. That cassette was gold

David Batchelor

Batchelor produced albums by the likes of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band (SAHB) and Scottish punks the Skids. He was the man behind the desk for Skids’ hits like Into The Valley and The Saints Are Coming and his work with the SAHB was an influence on everyone from Nick Cave to Joe Elliott, Bon Scott to Robert Smith.

“I’ve written some songs,” Noel tells him, pulling a demo tape out of his pocket.

Dave Batchelor remembers playing that tape and being bowled over. “Right away,” says Batchelor, “it was there. That cassette was gold. I loved it.”

Noel appreciated Dave’s enthusiasm. Sitting in the back of the tour bus the two men passed a spliff around and Noel told him about this band he was joining, with his brother Liam on vocals. “Look, if I get a deal,” said Noel, “I'll get you in – you can produce.”

It was a pipe dream, just talk.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“But he was true to his word,” says Batchelor. “That's exactly what happened.”

David Batchelor should have been the producer of the first Oasis album, Definitely Maybe. Instead, he was fired before the album was finished and re-recorded with Owen Morris at the helm.

Batchelor has subsequently been cast in most accounts of the Oasis story as an old guy out of his depth with one of the hottest British bands of the 90s. In fact, although it didn’t work out, Batchelor was perfectly placed to produce the first Oasis album.

The songs that Noel Gallagher had been writing borrowed from the history of rock’n’roll – and Batchelor had been playing in bands since the birth of rock music itself.

In the '60s, his band the Bo-Weavles gigged four nights a week in the clubs and dancehalls of Scotland, playing covers of songs by the Byrds and the Beatles, the Association, Chuck Berry, and the hits of Tamla and Stax.

In the late '60s, as music got heavier, The Bo-Weavles developed into Tear Gas, influenced by Cream and Hendrix, Batchelor writing the songs with powerhouse guitarist Alistair ‘Zal’ Cleminson, and joined by Ted McKenna, Hugh McKenna and Chris Glen.

In Batchelor’s words, “Tear Gas could play like fuck”. They were a great live band and they could play anything – jazz, rock, soul – and that was reflected in the name they chose when they hooked up with singer Alex Harvey: The Sensational Alex Harvey Band.

With Harvey up front, singer Batchelor – who’d become the vocalist when their original singer dropped out on the eve of a German tour – moved into production, where he had a front-row seat on the development of SAHB.

On the first day of rehearsals, Alex Harvey suggested playing I Just Want To Make Love To You, the old Willie Dixon number popularised by Muddy Waters and Etta James. Dave Batchelor remembers it like this:

Zal started playing the riff.

Alex said, “Turn it down a bit.”

Zal turned down and kept playing.

Alex said, “Turn down a bit more.”

Zal turned down.

“A bit more,” said Harvey.

“A little bit more.”

“A bit more…”

“Eventually,” says Batchelor, “you could almost hear the wood of the guitar as loud as what was coming out of the cabinet.

"Zal has got the loudest fingers in rock’n’roll. No matter what level he plays at, there’s an energy in his playing. It's just fiery. He's one of the top players in the world, I believe.”

That day, with Alex Harvey forcing Cleminson to turn down, he says, focussed Zal on “recognising the essence of a part – it's not always about blowing the back wall out.”

It was a lesson that Batchelor took with him 20 years later into the Definitely Maybe sessions.

Except that Oasis really just wanted to blow the back wall out.

Batchelor was assistant producer on SAHB’s second 1973 album Next and produced all of the band’s albums until 1977. In 1978, Virgin asked Batchelor to produce another band with an inspirational guitarist: Dunfermline’s The Skids. Into The Valley, written by guitarist and band leader Stuart Adamson, with lyrics by Richard Jobson, was a hit single in waiting.

Opening with a reverberating bassline and a rabble-rousing chorus, it was a perfect three-minute punk-pop song that sounded uniquely Scottish.

Skids roadie Clive Ford remembers the impact that Dave Batchelor had on the song. “I can remember the first time Dave met the band,” he says. “He was in the rehearsal room, and he’d been there less than five minutes. The band we're doing Into The Valley and he goes: ‘Hold on a minute. Can I make a couple of suggestions?’ And he just chopped the song around. And it was for the better.”

“Into The Valley wouldn't have been a hit as it stood,” says Richard Jobson. “Not in a million years.”

It went to no.10 in the UK charts.

Producing the Skids, and working with a band leader as perfectionist and principled as Stuart Adamson was not dissimilar from working with Noel Gallagher.

“Stuart wanted to keep the recording as close as possible to what we did live,” says Skids bassist Bill Simpson. “We only had one guitarist: Stuart. But obviously, when you’re in the recording studio, you have to have overdubs and layers of guitars and harmonies. Stuart just didn’t like it.”

Eventually, with the album almost finished, Adamson walked out on the session. He wanted their live sound - or the sound in his head. And he didn’t want anyone messing with it.

The engineer on the session, Mick Glossop, says Stuart Adamson’s reaction is not unusual. “That’s a common, and not unexpected, type of reaction that you might get from someone who’s unfamiliar with how you make records.”

One of the main initial hurdles for me was the drummer

David Batchelor

Fast-forward to 1993. After years of doing live sound for bands like Inspiral Carpets, Big Country, Ray Davies and more, Batchelor finds himself in Monnow Valley Studios, formerly the rehearsal space for nearby Rockfield Studios, with Oasis.

It went wrong before they even got to the studio.

“One of the main initial hurdles for me was the drummer,” says Batchelor. In the studio, the band would run through a song, and the producer would spot sections that could be lengthened, shortened, or ditched.

“Their drummer Tony McCarroll – he was young, a really nice guy. His instincts were spot on. A nice player with a natural, good feel in his playing,” says Dave. “But getting him to change his part, or the arrangement of the song, proved a hurdle for him.”

Batchelor suggested that they have at least a week of rehearsals before going into studio. But Noel disagreed. “So we had two days of rehearsals.”

The next problem for the producer was the engineer. Dave Scott had recorded demos with the band at The Pink Museum in Liverpool.

“He'd done a demo with them,” says Batchelor. “A really good demo. I liked what he did, but he was just taking over the whole thing.”

“I personally felt that Dave Batchelor was unhappy because Noel had chosen me to be the engineer,” Dave Scott told Oasis Recording Information. “As producer he should have had the say.”

The engineer and producer just didn’t gel. “I couldn’t connect with him artistically or technically,” said Scott.

This was just to the point where I had no input. It got out of hand. And they were smoking – just out of their heads most of the time

David Batchelor

Batchelor felt like the engineer was trying to lead the sessions. “He was plonking himself in the studio and just throwing everything at the guys,” he says.

“‘Okay, we'll do this, we'll do that’. And I don't mind, I've been there many times, anyone can come up with ideas – you recognise a good one and you go with it – but this was just to the point where I had no input. It got out of hand. And they were smoking – just out their heads most of the time.”

Dave Scott says he was fired over the tempo of Slide Away. When the band couldn’t nail the tempo Batchelor wanted, the engineer stepped in. It was one interference too many. “I said, ‘No, sorry – we'll need to get somebody else in,’” says Batchelor.

But he was starting to feel that it was slipping away. “I'd been out of the producing business for some time,” he says. “I wasn't really clued up on what the best studios were, who were the current top engineers, who were good guys. You need to be on top of all that.

“I wasn’t really up to speed to take on what they had to offer. I was busking it and relying on other things to be right, without knowing enough to say, 'No, we're going to that studio. We're going to use that engineer' – that kind of detail. That way you can sit back and relax and focus on the music.”

And when it came to his vision for the album he was thrown a little bit by comments Noel had made about his influences.

I showed [Noel] how to play This Guy's In Love With You on a hotel piano. He picked it up and off he went...

David Batchelor

Somewhere on tour with the Inspiral Carpets, they had sat down at a piano. “Noel was talking about how he loves the Bee Gees and Burt Bacharach and stuff like that,” says Batchelor, “so I showed him how to play This Guy's In Love With You on a hotel piano. He picked it up and off he went. It was good craic.”

(Later, Gallagher based his song Half The World Away on the Bacharach song – “It sounds exactly the same,” he commented. “I'm surprised he hasn't sued me yet” – and Noel played the drums on the track himself, apparently frustrated at McCarroll’s inability to nail it.)

When they went into the studio, those references stuck with Batchelor and threw him off-course. “You obviously have to have a vision,” he says. “And that vision was kind of disturbed a little bit by the Bee Gees and Burt Bacharach.

"I saw a strong song element to whatever he might want to do. So that was part of my thinking.”

The replacement engineer [presumably Roy Spong. Previous credits: The Pogues, Kirsty MacColl, the Pet Shop Boys] wasn’t ideal either. “He played me his show reel, and it’s as pristine as you could ever imagine.” So suddenly Batchelor was having to push against the engineer as well. “He wasn't really feeling it.”

And then, he says, he “made a schoolboy error”. At the mixing stage, he picked out a song that he felt was a single. “I thought, ‘I'll impress the record company. We'll mix this first, get it rocking’,” he says.

“But I was never really into the song and the proof was in the pudding because it never really happened – it didn't make on to the album. But, in a sense, it was my downfall in the eyes of [Creation records boss] Alan McGee. McGee comes in and they were listening to some of the stuff that wasn’t quite Oasis as we know them, and this track – it was rocking, it was good, but it wasn't a killer song.

“They were all in the other room, and the old white powder comes out, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah and I couldn't tune into it,” he says.

“I mean, I've taken the odd line on tour or whatever, but I've never been into coke at all – I've seen so much damage from it. So I couldn't tune in and I know what that's like: When the posse is taking cocaine, if you're not joining in, you're on the outside. The spell was broken. I got my P45.”

Noel claimed later that he sacked Batchelor. “We had the same record collection,” Noel told Mojo in 1995. “But he’s so old – he’s in his 50s, does front-of-house for Ray Davies and stuff – and I’m like 27.

"When it came to sitting at the mixing-desk, I’m pissed and saying, ‘Let’s get a bit mad here, let’s really let go and be young and compress the shit out of this so that the speakers blow up’, he’d go, [stubborn old-timer], ‘Nope, ’cos this is the way we done it in our day, son.’”

Noel just wanted to blow the back wall out. Like Stuart Adamson, he wanted the live sound he heard in rehearsals and onstage.

In his book Creation Stories, Alan McGee says that he pulled the plug on the Batchelor sessions: “Noel was innocent at the time and said, ‘Oh we’ll get it right by the second album’. There was no way I was going to take that risk – most of the time you only get one chance. We did keep Slide Away from those sessions.”

McGee put it down to Batchelor recording the band separately: “They were trying to record the instruments separately, something that never works for our bands. It was another of our links to the 1960s: our bands worked best when recorded live.” Oasis went to Sawmills Studios in Cornwall with Owen Morris and did just that.

The Monnow Valley sessions were released this year on the 30th-anniversary release of Definitely Maybe. What is most striking about them, after three decades of claims that they were too polished or sterile, is how similar they are to the finished album. Less overdriven, less loud, yes, but incredibly similar. The Dave Batchelor sessions had been a clear dry run.

“I stand by this statement,” says Batchelor: “They probably learned a lot from going into the studio with me. They would have gained a lot of ammunition, a lot of knowledge. They would be in a better place to decide how it should sound. And the way they made it sound is fantastic.”

John Cornfield, co-owner of Sawmills, seems to back that up: "They just went in there and bang, bang, bang - three takes or so and nailed it. You could tell they had played them a load of times as there was no messing about," he said.

You know, how he goes ‘Nyyyyyyyaaaaaaahh’ and he keeps holding on and holding on? I mean: he sounds great. But Jesus Christ

David Batchelor

Batchelor is philosophical. “I'd be sitting there, listening to what we’d recorded and it wouldn't be floating my boat either,” he says.

“There's stages that you need to go through to make it really take off. I wasn't given that opportunity. The confidence link had broken, and you can never repair that kind of thing.

“Maybe I wouldn't have been able to do them justice – but I might have been able to tell Liam to stop holding those sneary notes for so long. You know, how he goes ‘Nyyyyyyyaaaaaaahh’ and he keeps holding on and holding on?

“I mean: he sounds great. But Jesus Christ.”

The Definitely Maybe 30th Anniversary Edition, featuring the Monnow Valley sessions, is on sale now.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, which means he’s responsible for the editorial strategy on online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years. Scott appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.

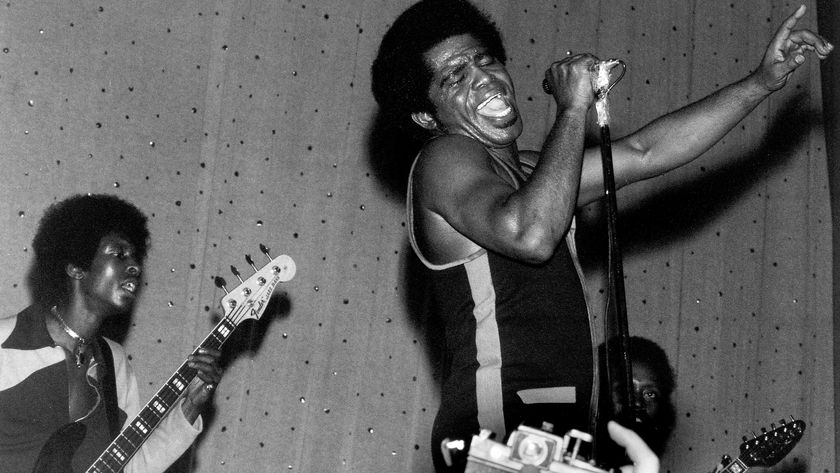

“James felt the fines would make you work harder. He was using that reverse psychology on us, and we didn’t understand at the time”: Bootsy Collins on why James Brown’s fines worked for his musicians

“Hybrid Theory came out and nu metal was everything. I bought the album and showed it to everybody at school": New Linkin Park singer Emily Armstrong says she was a fan of the band in high school

![Oasis - Live Forever (Monnow Valley Version) [Official Visualiser] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/pmPEsZHosh0/maxresdefault.jpg)