“It’s rumoured to have been used by everyone from Björk to Aphex Twin”: The history of making music with video games consoles

For many of us, video games were a potent point of introduction to the world of music production. We take a look back at the games and consoles that have inspired music-makers over the years

In 2003, a then 17-year-old Benga was challenged by the BBC to make a beat in his bedroom. His music production software of choice? Music 2000 for the Sony PlayStation. Yes, a video game console.

Although this may seem surprising in an era where anyone can make a beat with their phone, things before were very different indeed. Not every young person had access to powerful technology - but they sure as sprites had access to a video game console.

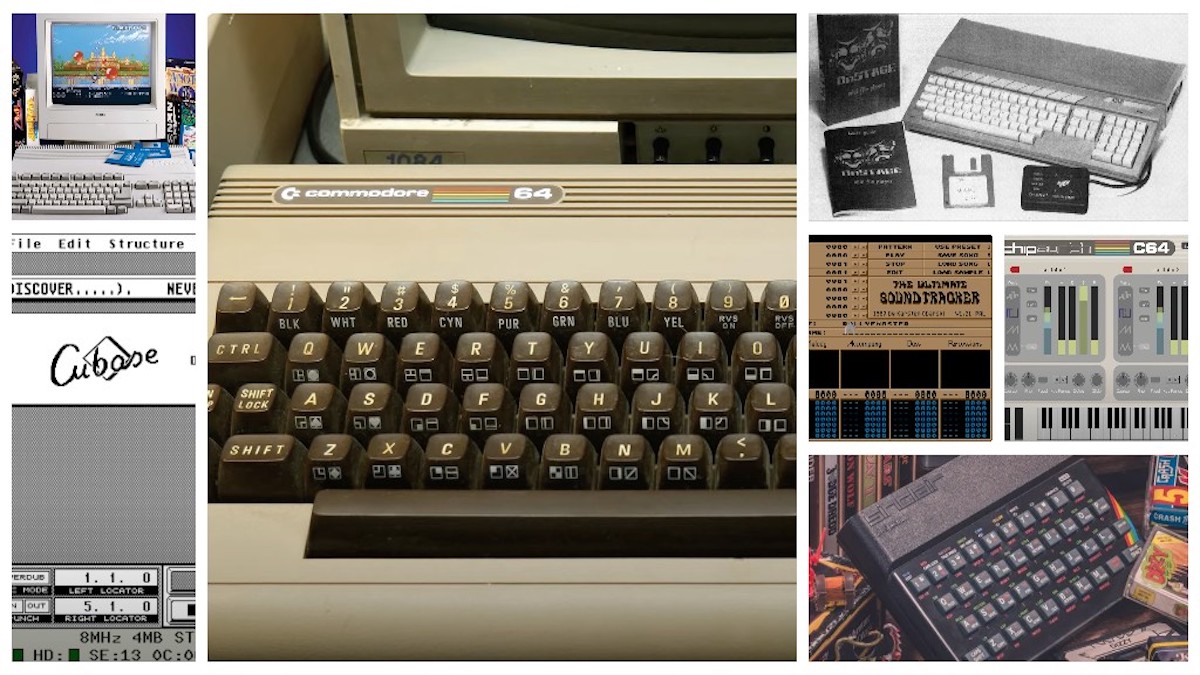

The story of video game console music production is nowhere near as well-documented as that of computers. We all know about the Atari ST and Amiga and what a big part they played in early dance music. But video game consoles? That’s a bit more obscure.

Let’s pull back the 8-bit curtains on this sidelined area of music production history and examine how sitting in front of a cathode ray television turned many of us on to the power of music and the joy we can find in making it. We’ll finish by looking at how you can harness the nostalgic and emotive power of video game console music production in a modern context.

In an era before the widespread adoption of computers, tablets and smart phones, video games were the first time many of us had the opportunity to engage directly with music-making.

"Music and beat games were important because they introduced gamers to wanting to make music"

“I think music and beat games were important because they introduced gamers to wanting to make music,” commented Norm Badillo, the Senior Art Lead/Technical Artist at Digital Eclipse, whose Atari 50 title blurs the line between video game and historical document. “With the amount of systems out there and the accessibility, people could learn or make music without having to put in money for classes or for specialized equipment. This generated a whole new interest in music, coming from a place of pure entertainment.”

For many of us, music-making video games were an introduction to the concept of music creation as entertainment; music-making framed as an enjoyable diversion, rather than a means to an end. Whether it was through a rudimentary sequencing program like Mario Paint, a rhythm game like Dance Dance Revolution, or even the first time we had the chance to use a piano-style keyboard, video game consoles functioned as a portal to a world where music was experienced not just passively, but interactively.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In the late 1980s, there were few ways that you could connect a controller to a PC to engage with music software, let alone a video game console. But in 1987, Konami released what is considered to be the first console keyboard controller as part of DoReMikko, a music-making title for the Japan-only Nintendo Famicom Disk System. You could hook the mini key controller (it looks remarkably like a Korg Micro Key) up to your console and jam along with a band, play different instruments and even record your performances to the built-in disk drive.

Non-Japanese music fans would have to wait until 1990 for the cross-platform Miracle Piano Teaching System from The Software Toolworks, which also included a MIDI keyboard controller. This one provided lessons to help you learn songs. There was even a game section where the piano keys could be used to control gameplay. Don’t be surprised if you’ve never heard of it; the $500 price tag kept sales very low.

Tucked away inside Nintendo’s Mario Paint, a 1992 Microsoft Paint-style art title for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System that came bundled with a mouse, was a music composer section. By stringing notes along in a score-style GUI, with 15 sampled sounds available, it was possible to make rudimentary songs. It was very limited - there were only eight melodic sounds with no sharps or flats possible! - but for the budding composer, it was a real boon.

These days, there’s a rather large community of musicians who embrace the limitations of the game - although they use computer emulations to do it rather than vintage SNES machines. Mario Paint Composer is the OG emulation but there are a variety of PC recreations, including Super Mario Paint. For a taste of what’s possible, check out Mario Paint Works by Booji Bomb, an album made entirely with Mario Paint.

At the turn of the millennium, two independent developers had roughly the same idea: create a DIY cartridge to turn the Nintendo Game Boy into a music sequencer. Those two titles, Nanoloop and Little Sound DJ, would go on to have a massive impact on the world of electronic music, helping to spawn the chiptune genre and bring the sound of old-school games into modern productions.

“Chiptune music exists at the junction of music, gaming, and nostalgia,” Matthieu Gallais, the Creative Director at Eidos Interactive, said. Gallais is not only involved with video game creation, he’s also a chiptune musician who records under the name Pixoshiru.

“As a genre, it is infused with signature sounds that evoke a specific era of gaming that anyone who grew up with a Game Boy, an NES or an Amiga will relate to. As a culture, it is vibrant, welcoming and playful. As a medium, it is a very unique approach to composition, focused on technical limitation and idiosyncratic tools, notably trackers.”

While trackers are often associated with computers like the Amiga and old-school jungle and IDM, they're a big part of the chiptune scene as well, as Matthieu said. This is largely because of the efforts of one Johan Kotlinski, the creator of Little Sound DJ. LSDJ (as it’s known to its users) is a tracker-based DIY cartridge that lets you turn a Game Boy into a music-making machine. It’s rumoured to have been used by everyone from Bjork to Aphex Twin and even Kraftwerk. That’s quite a CV!

“I don’t care too much about famous people,” Johan remarked when asked about this. “But it was interesting and crazy when chip music briefly got mainstream and artists like Beck and Timbaland leaned into the sound.”

Johan, who has also worked at Teenage Engineering on software for the OP-1 and KO-II, had been making music with Amiga trackers but wanted to try something new, he explained when asked how he created LSDJ. “The Game Boy Color was new at that time,” he continued. “It seemed like a fun retro-style machine, and I thought it could be a nice way to learn assembly programming. Its sound was relatively unexplored, and the portability was a nice bonus. I was surprised at how fun it turned out (to be). It was a perfect fit for me and many others.”

Johan continues to update LSDJ. “I have been releasing free upgrades regularly since then. Hopefully, there is still more to come for the 25th anniversary (next year)!”

According to the LSDJ site, the most affordable and reliable way to use the tracker is with a Game Boy emulator on a computer. If you insist on doing it the old-school way, you’ll need a reprogrammable flash cartridge. The ROM is free to download.

Nanoloop is the other well-known sequencer for the Nintendo Game Boy. As the name suggests, it’s not a tracker, but works more like a drum machine with a looping step sequencer. The 16-step sequencer appears as a 4x4 grid, much like on an MPC. You get access to three tonal sounds - two rectangular waves and a custom wave - plus noise. And that’s it. The trick is getting as much tonal and rhythmic variety out of the limited palette as you can.

Nanoloop is available in a number of different configurations and formats, with versions for the original Game Boy and Game Boy Advance plus iOS and Android devices. It also works on emulators.

If you’d prefer to engage with hardware but don’t fancy buying something vintage, you can also find Nanoloop inside Pocket, a new handheld console that can run Game Boy, Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance carts and - crucially - comes preloaded with Nanoloop.

In 1999, most electronic music producers were still working with hardware. Fully in-the-box music setups were few and far between. Kudos then to Codemasters, who released Music 2000 (called MTV Music Generator in the States) for the first Sony PlayStation, letting a generation of young people not only sequence music but also sample with software, something that most adult producers couldn’t even do at the time.

This is the console title that launched the careers of countless 2000s dubstep and grime beatmakers, including the aforementioned Benga and his frequent collaborator Skream. While there are rumours that Benga, Skream and even Dizzee Rascal made actual records with Music 2000 (they most likely didn’t), seminal grime track Pulse X from Youngstar is widely considered to be a Music 2000 production.

As with many of the other old-school titles in this list, there are emulations out there if you’d rather not spend your evenings trawling eBay for a used PS1.

Of the big three Japanese musical instrument companies, that being Roland, Yamaha, and Korg, the latter has always done things a little differently. One thing that’s set them apart from the other two is a willingness to reconceptualize what a synthesizer can be. A piece of hardware? Definitely. A software emulation? Yes, sure. But a video game?

In 2008, Korg took the unusual step of digitizing its 1978 analogue classic MS-20 into a title for the Nintendo DS handheld console. Called the DS-10, it features two “analogue” synthesizers based on entries from the original MS series. These have two oscillators, each including sync, which none of the original hardware models had. Additionally, you get a four-part analogue-style drum machine, effects and a step sequencer. Pages are spread across the DS’s two screens and you can use the included stylus to make adjustments. Most importantly, it sounds great.

So great, in fact, that Jamie Stewart of Xiu Xiu has used the DS-10 on a number of occasions - both live and on record. When asked why they liked the DS-10, Jamie said, “Its immediacy and portability. You can use it anywhere for only a few minutes and get something interesting done.” They used it “extensively” on the Dear God, I Hate Myself record and for drones on Unclouded Sky.

Another artist who favors the DS-10 is Mattelica, whose name comes from a childhood fascination with electronic sounds made by the pocket games of toy manufacturer, Mattel.

“What I like about using these types of tools is that the sound quality is different from your standard synths,” Mattelica said. “I like the challenge of making cool sounds and tracks with small, portable, and low-cost tools.”

Korg has continued its relationship with handheld Nintendo, releasing M01D, an M1 emulation, and DSN-12 on the Nintendo 3DS as well as a port of Gadget, its self-contained DAW originally released on the iPad, for the Nintendo Switch.

If you’d like to incorporate some of that old-school console flavor into your productions but don’t fancy dealing with the actual hardware or even emulators, there are still a number of options available.

Think outside the box by using your hands in a different way. Try using a game controller as a MIDI controller. Most modern game controllers are essentially just plug-and-play USB MIDI controllers. MIDI map the buttons to your DAW or soft synth, or use a MIDI device like Light Reft’s Monolit as an intermediary control device.

If you’re a beatmaker or finger drummer, look into replacing your usual grid controller with a Midi Fighter, which use arcade-style buttons rather than rubber pads. If you like the sound of old games but not the interface, there are plenty of instruments both hard and soft based on old game chips. Plogue’s Chip Synth MD emulates the FM chips in the Sega Genesis, while Sonicware’s Liven Mega Synthesis does the same thing in hardware form.

Lastly, try using a tracker like Dirtywave’s hardware M8 or the Renoise DAW to compose rather than sticking to your usual piano roll. You’ll find yourself coming up with phrases and rhythms that you normally wouldn’t - which is the whole point, right?

Adam Douglas is a writer and musician based out of Japan. He has been writing about music production off and on for more than 20 years. In his free time (of which he has little) he can usually be found shopping for deals on vintage synths.