“I didn’t know anything about drugs or any of that stuff. For me, acid was a chemical that stripped away paint”: A Guy Called Gerald on the birth of acid house

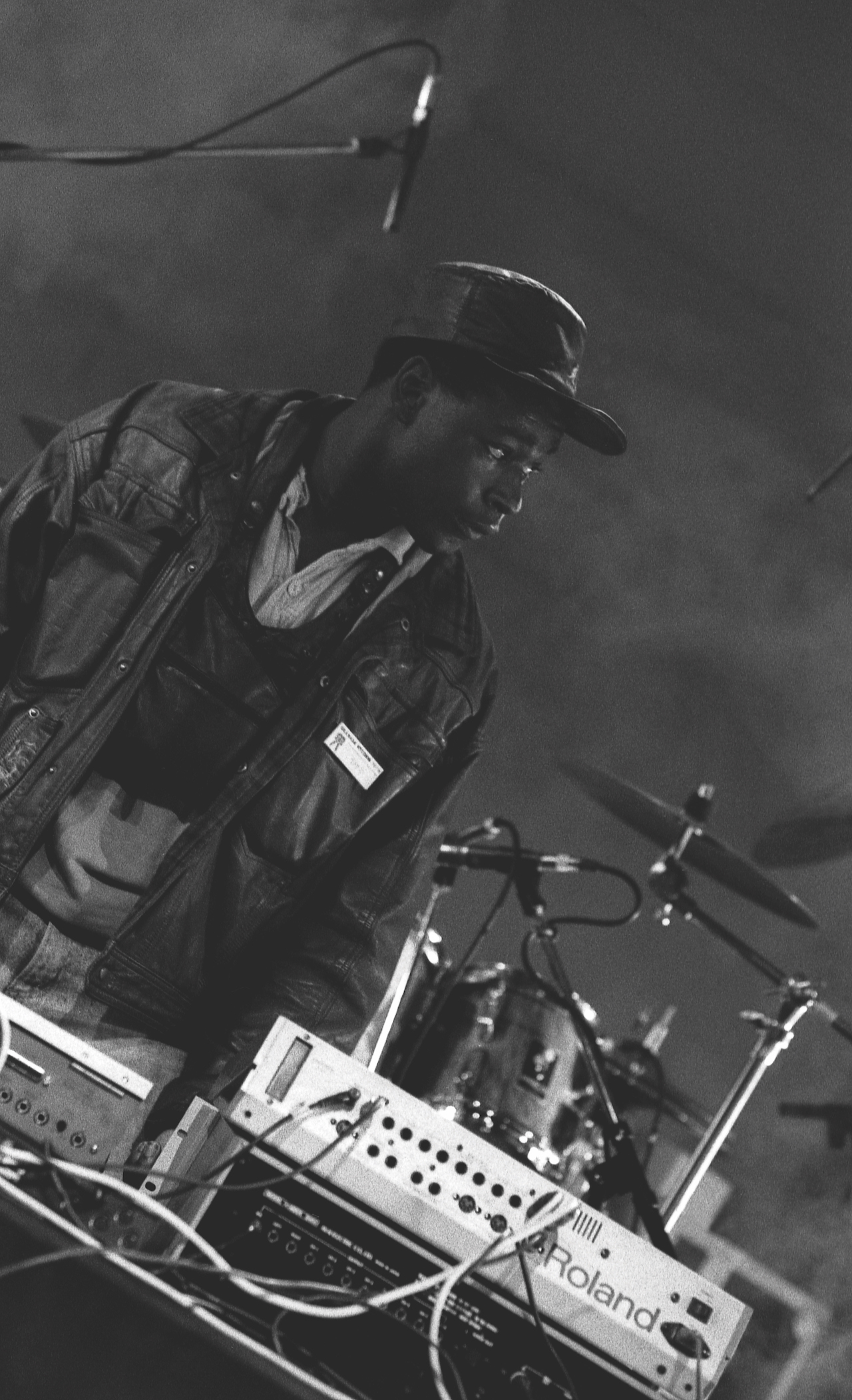

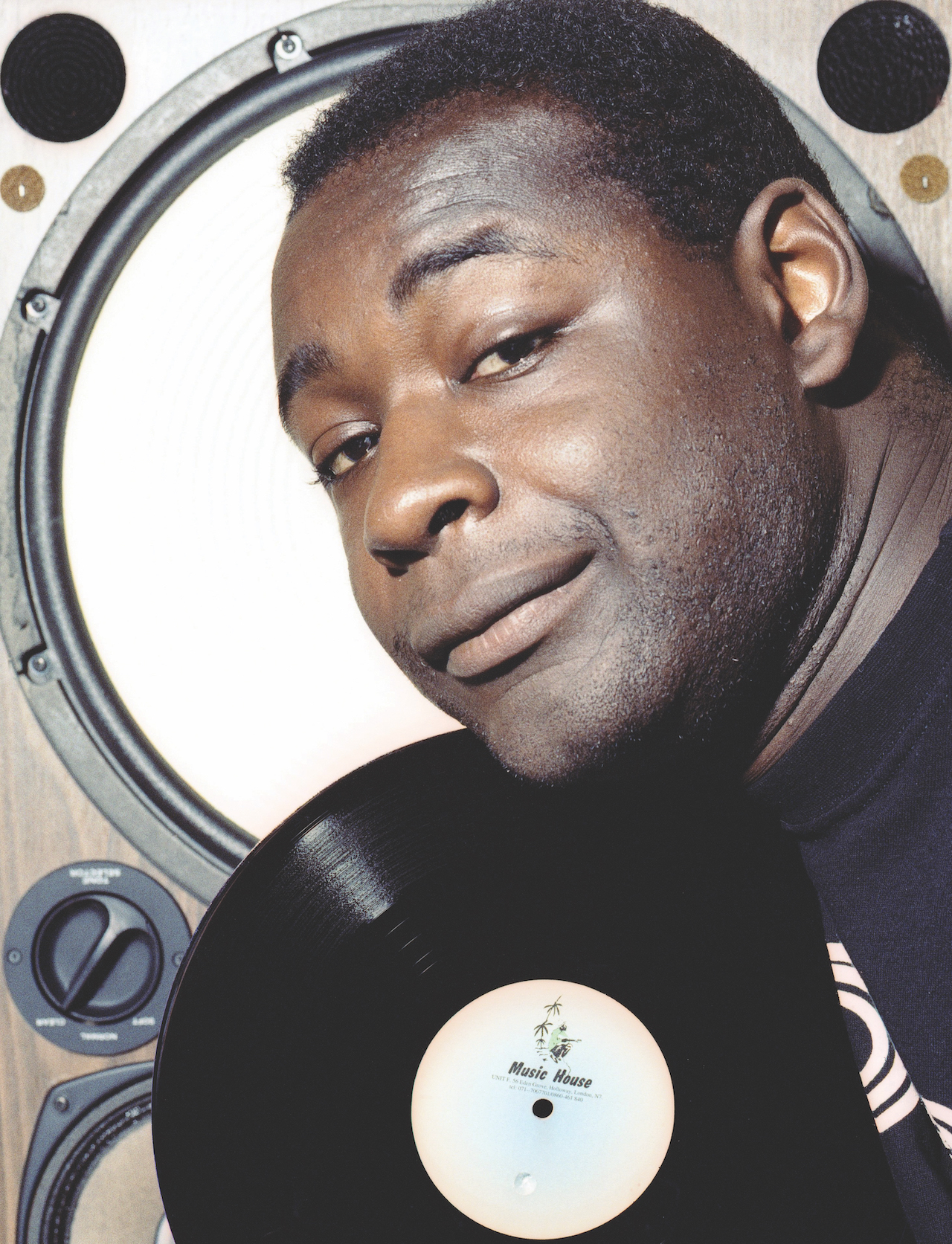

The acid house and jungle icon sits down to tell us his history with the 808, 909 and 303

Manchester-born musician Gerald Simpson is one of the most important figures in the history of British dance music.

In the late-’80s, as a solo artist and member of 808 State, he helped pioneer the British strain of acid house, releasing iconic tracks such as Pacific State and Voodoo Ray. As the ‘90s rolled around, Simpson moved from house into jungle, experimenting with early samplers and breakbeats, eventually releasing the influential album Black Secret Technology.

Throughout his career, A Guy Called Gerald’s music has been tied to certain pieces of equally iconic music technology, specifically Roland’s genre-defining synth and drum machines, including the TB-303 and SH-101 synths and TR-808, TR-909 and TR-707 drum machines.

As part of this year’s Brighton Music Conference, we sat down with Gerald Simpson to talk about his relationship to those Roland machines and how that technology helped shaped his career.

Take us back to what you were using when you very first started making electronic music…

“My first introduction was an Amstrad stack-like thing with basically a Boss drum machine and a double tape deck, which was really important. I was basically playing the drum machine in and then scratching on the turntable over the top of the drum machine. I would do tapes like that. Kind of like electro beat type things because I’d seen Grandmixer DST playing with Herbie Hancock at the Apollo, doing the track The Rocket. I’d seen how he scratched – and I’d heard the scratching sound before that, on Buffalo Gals and all that – and I just thought it was a synthesiser or some new thing. But then when I’d seen him doing it, it was like ‘wow I could do that’.

“I had this little drum machine that I used to use for dance practice actually. I was studying to do contemporary dance at the time, to keep myself out of trouble [laughs]. I started to use this drum machine and then from that I got the Roland 808. I got that from this music shop I’d visited since I was 14 or 15. I went downstairs into the basement where all the synths were and there were a few second-hand things. And there’s this box I’d never seen before – but I heard it a million and one times, and I was like ‘I want that’. Basically I just started to collect all my pennies together. I worked at McDonald’s. I worked all the weekends, stole other people’s weekends. Got paid more than the managers. But the drum machine was something like £150 in the end. This was 1985 to 1986, I think.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

For context, did you have a reference of which other artists were using what gear?

“The only reference I had was records; so like Planet Rock, then there was The SOS Band and all that kind of stuff. All the stuff that I heard on Piccadilly Radio. A load of American import music. It was all kind of 808-orientated.

“I had loads of ideas about what I wanted to do, and how I wanted to work in the studio. There was a track called Renegades of Funk by Soul Sonic Force and I knew that they were using the separate outputs on the back of this drum machine and those were being put through separate effects. I had to find a way to do that. But I knew [the 808] was the drum machine that they did it with. I got a few guitar pedals and I tried it out myself.

“I was constantly buying studio gear and equipment to sit on the table – just home-type stuff – four track and pedals and all that. You’d have to just make the stuff up yourself. Like, putting, you know, flangers in a daisy chain with a reverb. Stuff that you could quite easily do on a laptop now [laughs].”

Tell us about how you started using the TB-303, which is obviously a cornerstone of acid house. At what point did you encounter that first?

“1987, something like that. It was basically being sold as a band-in-a-box type thing with the 606 and I found it in a second hand shop. I knew of it before then, because I think I’d seen someone playing around with one somewhere. But I found it in this second hand shop called Johnny Roadhouse Music. And it’s got like this five-pin DIN on the back, which was the same as on the back of the drum machine that I had. In those days, hi-fis had pin-DIN. So you could plug your tape machine into your tuner via this 5-pin DIN. So I plugged it in and it worked. And it was like, ‘why do I need to have anybody else play a bass when I can automate this kind of thing myself?’. I was pretty much a loner. So it was a way of basically putting bass through onto the drums and then on from the drums to the tape machine.”

How aware were you of what other people were doing with the 303 in those days? Was that kind of music coming over from Detroit? Had you heard the word ‘acid’ in that context?

“This is a little bit before acid, it was the electro funk days. I was well aware of stuff that was going on with electro funk and what you could do with a bass machine. If you could program the drums in the drum machine you could program bass on the bass machine. I was aware of that. The first thing I heard might have been Ice-T,6 in the Mornin’. That was the first thing I heard, with the 303, but it was just a raw 303 with no changes.

“I think it must have been a year later or something I was in, like, the video shop and I heard on the radio something that sounded like my machine. I was like, ‘oh my god what’s that?’. It was on Piccadilly Radio – probably [influential Manchester-based DJ] Stu Allan by then. He said the track was by Phuture. So obviously I went straight down to the import shop to find out what was going on.

I found out there was this stuff called acid house. I didn’t know anything about drugs or any of that stuff.

“I found out there was this stuff called acid house. I didn’t know anything about drugs or any of that stuff. For me, basically acid was a chemical that stripped away paint. I was thinking acid house was stripped down funk; because everything rotated around funk. Like jazz funk, electro funk so you know… acid funk. We kind of worked out ‘okay yeah it’s just a drum and this bass kind of thing’; and the bass was basically doing the talking over the top of the beat, which is basically reminiscent of disco. So I was like, ‘okay let’s go back to disco’. All this stuff was floating around in my head – like electro funk combined with disco, but stripped down.

“At the time there were only really a few acid house tracks around. I wouldn’t even call them that. They were more elaborations on things that were around [Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk’s] Love Can’t Turn Around and a few other little bits and pieces like that. It was all about jacking. [Raze] Jack the Groove came out, and so many other kind of ‘jack’ things. Then I started to pull on that kind of vibe. By accident in a way.”

For anyone who’s not actually used an original 303, they’re notoriously weird to actually program. How were you working with that? Were you trying to properly replicate basslines in your head?

“I didn’t know that they were supposed to be hard. I mean, I was programming it like the drum machine so I didn’t realise that it was supposed to be hard. I found a way basically. Everything was by kind of serendipity and by accident.

“I spent a lot of time on my own, just trying to figure out each one of these machines, and over time I actually learned how to write on it – I mean I could do Happy Birthday to You without the manual. Typing out the melody first and then afterwards tapping in the rhythm [mimes programming ‘Happy Birthday’].

“I could do that live too. Live, I would literally be programming the 303 at the same time as I’m putting things into the SH-101 sequencer, which I was programming from the accent of the 808. So I was running around like a mad rat. I started to write down little notes to memorise the tunes. I’d have this little book of notes open whenever I was doing a gig.”

Tell us about the rest of the setup around that time of those early releases. Where did things like the 909 and the 101 fit in?

“All this stuff, people were basically throwing it away. I had two SH-101s, the TB-303, an 808. The 808 was giving DIN-sync to the TB-303 and it was giving clock to the two SH-101s. The clock was coming from the cowbell to one of the SH-101s, and from the accent to the other one. That was my main system.

“Then I got a 727, which brought percussion into the mix. Then I got a Juno-106 to do the pads. People were just giving this stuff away. If you look at the old magazines you could see the price of things slowly started to rise. By the ’90s it was over; you couldn’t get anything. I was getting stuff from Akai. I was sampling some of these machines. People became aware of what they could do.”

You mentioned using guitar effects pedals. Were they part of the live show? Did you have any particular effect pairings that worked well with the 808, for example?

“I would mimic some of the things I would hear. By then I was combining what I was getting from Chicago and Detroit in my own little way. I actually liked what Derrick May and these guys would do with hi-hats and a flanger; so I would put flanger on the hi-hats and reverb and chorus on the bass. That was really nice. Just treating stuff with delay, and tapping out delays so that it would make this whole other pattern. You’d only have to use really simple elements and it would create like this whole movement. I suppose it started to get really dubby and strange at some points – big reverbs on snares and claps. I had this stuff going through auxiliaries by the end of it.”

By the early ‘90s you changed up your sound and were moving towards making jungle. Was that a reaction to what was going on within house music?

“Oh yeah I think I was really pissed off. I felt this abuse from the music system that I didn’t realise would have happened. I still wanted to create, so basically jungle was letting off steam. I remember at one point, one of the guys from 808 State said ‘I don’t like breaks’. And I was like [adopts sardonic tone] ‘Oh yeah, really?’. The first thing I did was a track called Specific Hate and I used this break beat. I was like ‘this is alright, isn’t it?’

“After that I kind of continued with the breakbeats and did a sound system called Juiceboxx with Nicky Lockett who’s from my estate [MC Tunes] and then I decided ‘yeah let’s do some tunes’. Like dubplates. We started doing these breakbeat tunes and the rest was history, really.

“By the end of it I was just trying to find a way out of Manchester. Crazy things were going on there. People with firearms and stuff. But I managed to evade all that and focus on what I was doing and I just kept with the music. I managed to get away with my life and escape. The people that were doing jungle at the time wouldn’t come to Manchester so I had to go to London [laughs]. Nobody in London wanted to keep guns in my house.”

Was there any place for those Roland drum machines in your new music, or did you completely make a break with them?

“What I thought I was doing at first was a step on; but I found that there was a lot within the sampling [domain] that was really similar. I was happy that I’d learned about envelopes and attack, sustain, decay and release because that came in very handy when it came to smoothing in loops and stuff like that. I did a lot of looping, a lot of cutting and listening to how I wanted sounds. Stuff like that. Trying to create… not a natural acoustic… but, like, I knew how I wanted the bass drum.

A lot of it was about trying to show off your production skills to the other jungle teams

“With the 808 bass drum, there was only a certain amount that you could do with a real 808. Within the sampler – I was using Akai mainly – I could actually lengthen the sample out and lower and make it sing how I wanted it to. We were cross-platforming a lot of different genres by then. I was mixing dub with hip hop and trying to create new sounds.

“A lot of it was about trying to show off your production skills to the other jungle teams. I had a few secret weapons. A lot of people didn’t realise I was recording onto tape at first, because they couldn’t figure out how I got the bass so deep. You know, I would record really fast and then slow it down, so it was really clean and deep. Then the actual tone from the Akai is a really nice thing to use too. A lot was going into really simple things. A lot that you couldn’t really do earlier on.

“The first thing that I did when I got a little bit of revenue was get a studio, a desk and outboard gear. I didn’t bother with people after that. I was like locked in the studio trying to get as deep with my bass as possible, as crisp with the snares as possible – wanting to know about the science of stereo imaging. I needed my acoustic to be focused. I just basically started to go down, like, all these different musical rabbit holes.”

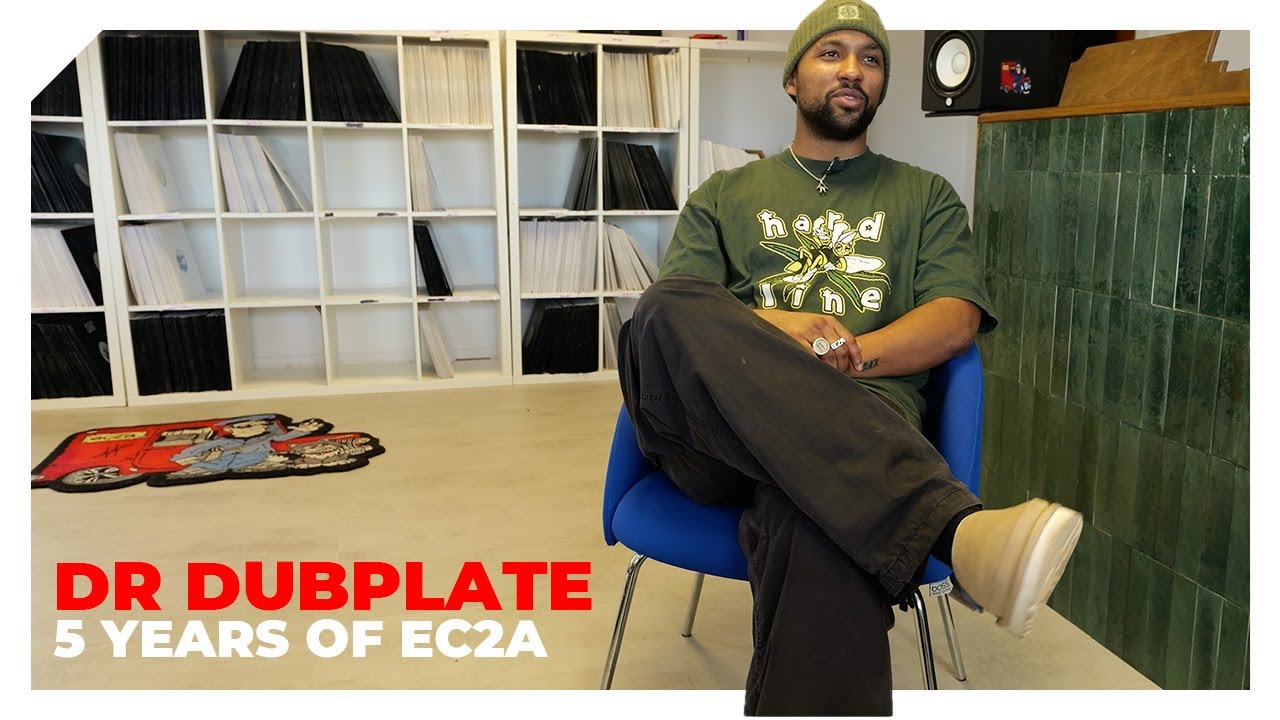

Last time we saw you play live you were DJing with two copies of Reason. Is that still what you use?

“That’s the heartbeat of what I’m using, yeah. I’m so used to using that. I realised that it doesn’t use so much CPU – or it didn’t, it’s slightly bigger now – and on top of that, they basically stole the Solid State Logic desk and put it inside – and that’s my desk, man. So now, it’s not possible for me to jump to FL Studio or anything else because I can create the sounds I want and shape them in the way that I want inside Reason. But then I started to add other elements too. Basically because people like to see how it all works, and I like to add a little bit of edge. So I started to bring some of the Analog Circuit Behaviour machines from Roland.”

How do you find those modern versions, having used the originals extensively?

“I mean, I get all this stuff about ‘feel’, but once I’m in the music I don’t care if that’s the button or that’s the button. If I’ve got my eyes closed and sounds are changing when I’m moving [the controls], I don’t care what it is.

“I don’t really want to be selling Roland, but when they came up with Analog Circuit Behavior basically everyone just thought it was digital. They thought they’d sampled something digitally and plonked it in the machine. But what they’ve done, which I thought was really clever, they’ve taken the actual circuitry from these old machines and put that in as a kind of digital circuitry inside the box. So you can get basically the same sound. People act like they can tell the difference. What I should try and do is encourage people to turn up to the club with an oscilloscope [laughs].

“Even if it was just digital, it’s impossible for me to bring the original machines on tour anymore because of the price of them and I get hassle from customs – I mean, they take the machines apart and they lose screws on purpose. Anyway, so I started to use the ACB things, which was a godsend for me. They helped me out. I can basically perform in the box and out of the box at the same time. Usually I don’t use the machines connected to the computer, so I have to manually make sure the tempos are the same and everything.”

“I like to keep the computers separate to the synths, as I like to have stuff that’s outside the box. In case I want to basically do crazy shit or if serendipity happens. I’ve got mainly structured stuff happening inside the box and then unstructured stuff happening outside the box.”

One final question: what would be the single thing that you’d tell a younger person who might be trying to get into making music?

“I would say basically to take a lot of care with your portfolio. Think of your music as your portfolio and don’t give it out. Before your music leaves your studio in any way, put an ISRC code on it. Because it can go to an aggregator, which will rinse the hell out of you. That’s the International Standard Recording Code. It’s a unique fingerprint like an ISBN number for a book. But it’s for your music – it’s not for Universal, it’s not for Spotify, it’s not for anybody else to have that – that is your code for you. It [links] your music to your portfolio.”

Keep up with the latest from A Guy Called Gerald at his official website.

I'm the Managing Editor of Music Technology at MusicRadar and former Editor-in-Chief of Future Music, Computer Music and Electronic Musician. I've been messing around with music tech in various forms for over two decades. I've also spent the last 10 years forgetting how to play guitar. Find me in the chillout room at raves complaining that it's past my bedtime.

![James Hetfield [left] and Kirk Hammett harmonise solos as they perform live with Metallica in 1988. Hammett plays a Jackson Rhodes, Hetfield has his trusty white Explorer.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/mpZgd7e7YSCLwb7LuqPpbi.jpg)