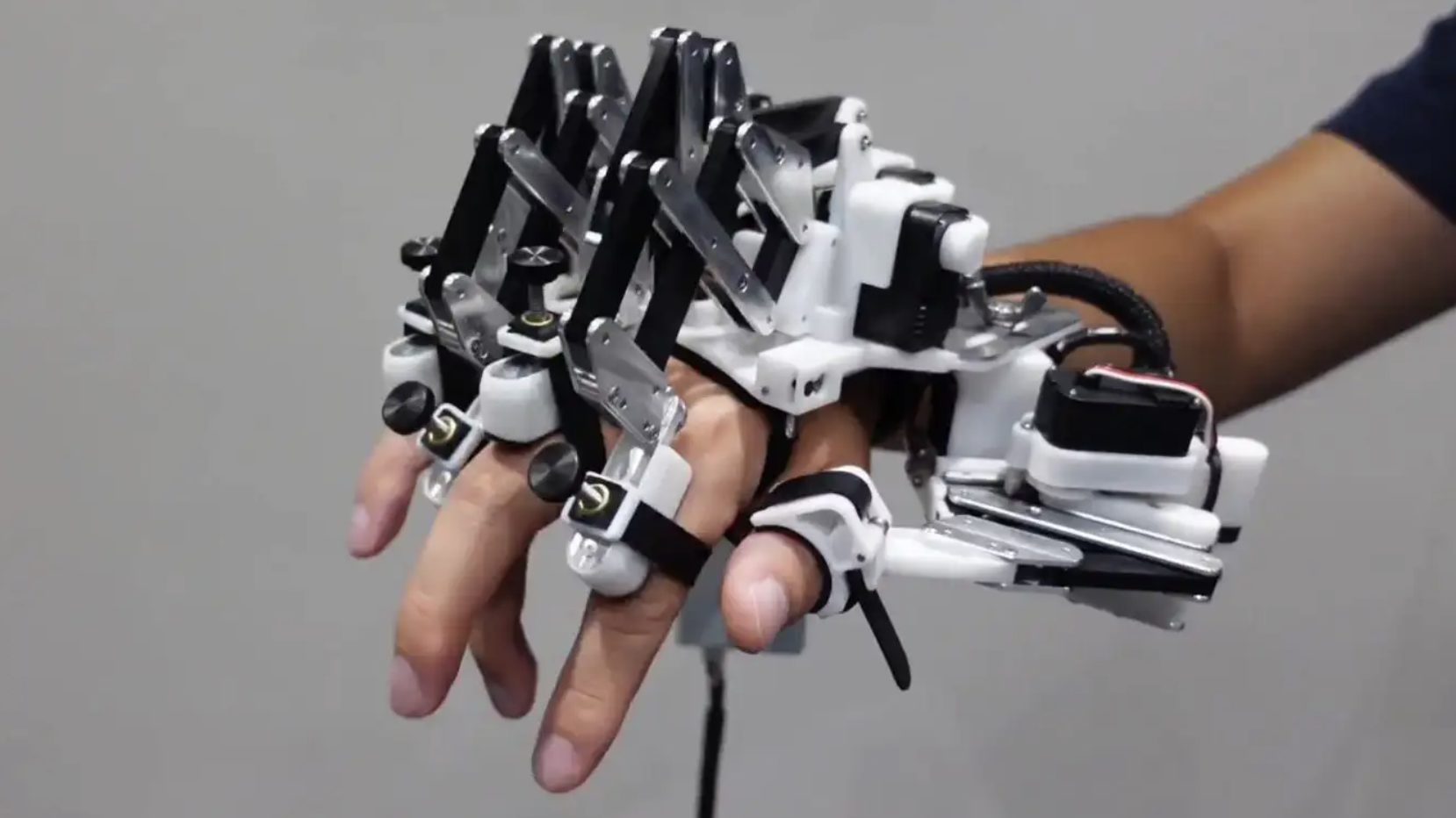

Could this robotic glove make you a better piano player? Researchers give pianists a helping hand with exoskeleton that improves finger speed

In a recent study published in Science Robotics, pianists showed measurable improvements across both hands after a 30-minute practice session wearing the device

Achieving an advanced level of proficiency on any instrument is a considerable task that often requires not years, but decades of focused and consistent practice.

Early on in that journey, improvement comes quickly. Once the upper echelons of instrumental talent are reached, however, many musicians reach a plateau, finding that even the most militant practice regimen provides them with diminishing returns.

Nicknamed the “ceiling effect”, this is the phenomenon addressed - and seemingly overcome - by a recent scientific study that takes a somewhat unconventional approach to building chops. By attaching a custom-built exoskeleton to their hands that moves their fingers independently, a team of researchers has managed to measurably improve the skills of virtuoso pianists, even once the device has been removed.

The exoskeleton, resembling a kind of fingerless glove equipped with motors that move the fingers and thumb up and down by up to four times a second, allowed the pianists to play a passage faster than they were previously able to, simply by moving their fingers for them as they remained passive.

Astonishingly, once the exoskeleton was removed, researchers found that the pianists’ unaided performance of the same piece of music had improved, and that their speed was enhanced by almost 30% after a single 30-minute practice session.

Recounted in a paper published in Science Robotics, the experiment was led by Japanese researcher Shinichi Furuya at Tokyo’s Sony Computer Science Laboratories. The study’s 118 conservatory-trained participants were all deemed to be expert pianists, having played since the age of eight and practiced for at least 10,000 hours before reaching 20.

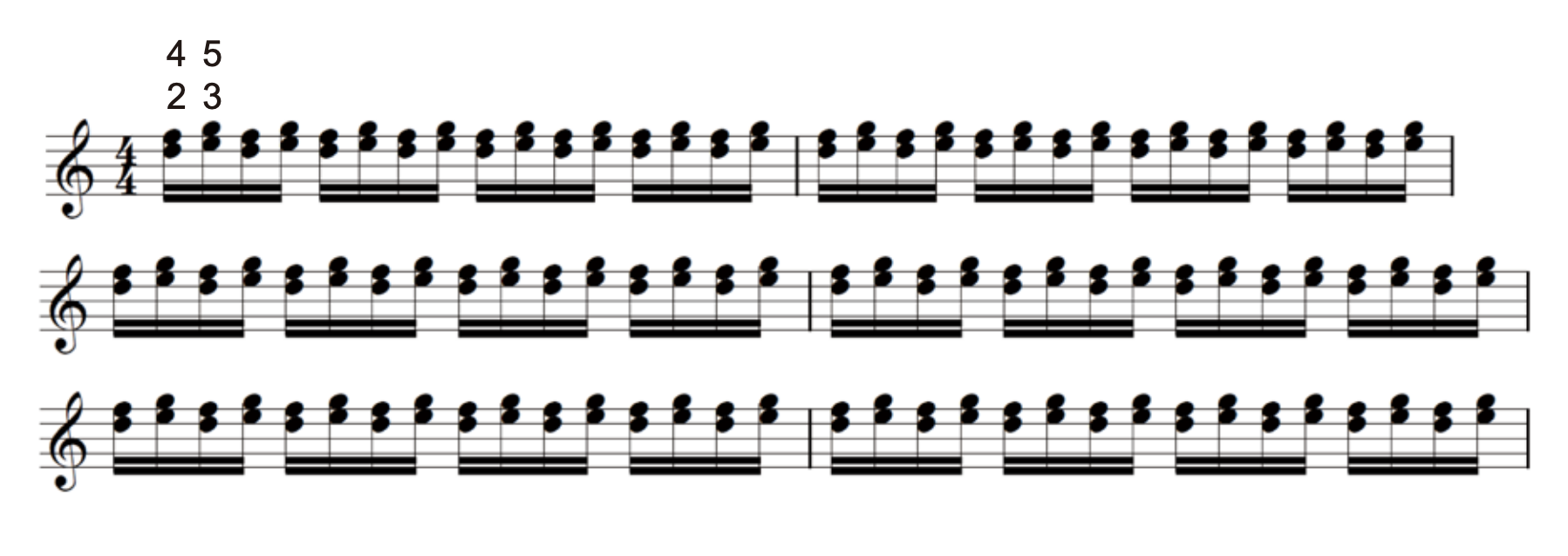

In the two weeks leading up to the experiment, the pianists were asked to practice a repeated chord trill on the piano that would be technically challenging to play at a high tempo; the pianists were asked to practice the passage daily, 30 times a day, measuring their performance at regular intervals throughout the two-week period.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Those tests confirmed that after experiencing improvements early on in their practice period, the pianists' speed and dexterity eventually hit a ceiling. Then, they were asked to come into the lab and split into several groups before undergoing a 30-minute session with the exoskeleton fitted to a single hand.

A control group had the pianists had the device open and close their fingers, while another group had the exoskeleton make them perform the same passage that they'd been practicing at home, only faster than they were able to play unassisted.

Once the device had been removed, the researchers found that the latter group had defied the ceiling effect, showing measurable improvements in speed and co-ordination, even after a day's time. Surprisingly, it wasn't only the hand that had been fitted with the exoskeleton that showed improvement: the other, untrained hand also became faster, thanks to a phenomenon called the intermanual transfer effect.

I thought, I have to think about some way to improve my skills without practising

Furuya told the New Scientist that the idea for the exoskeleton was born out of his own experiences as a young pianist. “I’m a pianist, but I [injured] my hand because of overpractising,” he says. “I was suffering from this dilemma, between overpractising and the prevention of the injury, so then I thought, I have to think about some way to improve my skills without practising.”

Furuya had his lightbulb moment after a teacher demonstrated how to play a piece by placing their hands over his on the piano. “I understood haptically, or more intuitively, without using any words,” he continues. This led him to question whether the same experience could be recreated with robotic assistance.

While the results of the experiment are undoubtedly fascinating, whether the technology could be adapted to become a genuinely useful tool for pianists honing their skills remains to be seen.

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.