What is harmonic planing and how to use it in your playing, compositions and productions

If it sounds good, it is good!

I attended the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, Maryland. In my theory class, Professor Thomas Benjamin introduced me to the concept of harmonic planing.

Whereas most 19th-century harmony deals with tonic-dominant-tonic motion (and its many alternate paths), 20th-century harmony is a completely different animal altogether.

Composers like Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, Olivier Messiaen, and many others (notably jazz pianist McCoy Tyner, shown above) threw the theory and voice leading concepts of previous generations out the window and basically said, “If it sounds good, it is good!”

Jazz harmony, which of course has undeniable roots in 19th-century European music (in addition to African rhythm, blues, and spirituals), made great use of 20th-century harmonic concepts. When you consider that Charlie Parker cited Igor Stravinsky as an influence and that Stravinsky was influenced by ragtime and jazz you come to understand the cross-pollination that has occurred between musical genres over the years.

In planing, instead of chord motion being based on voice leading and root movements, voices move according to the key or scale (as in diatonic planing), or the same voicing may move around chromatically (as in chromatic planing). Let’s take a look at planing in action.

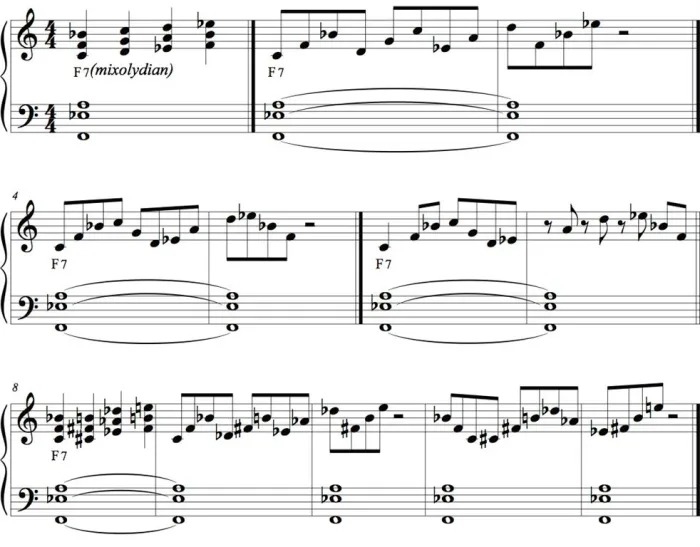

1. Diatonic planing

Ex. 1 illustrates diatonic planing, i.e., moving voices around according to the scale or key. Note that you can move all kinds of chord shapes around triads, fourths, or whatever you want. With planing, you don’t have to worry about root movement. You only need top be concerned about how one chord sounds after another.

2. Chromatic planing

Ex. 2 demonstrates the same idea in chromatic form. Here, we’re moving triads and fourths around chromatically. This is where things start to get interesting...

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

3. Mixed planing

Ex. 3 shows different practical applications of planing. First, we see a typical jazz voicing for minor chords moving around randomly. Next, we see the same idea with a dominant 7#9-type voicing. The important thing to remember here is that the 7#9 chords are no longer functional; they’re simply colourful sounds that move according to where you want the melodic line to go. The next two examples use a minor b6 chord that sounds intriguing, and then my own planing creation: a Gbmaj7 in the right hand over an Emin7 in the left hand. The point being, once you find a sound, it’s up to you where you want to take it!

4. Solo planing

Ex. 4 demonstrates ways in which you can use planing to create solo lines. With this technique, the chords become the melody. Obviously, the more creative you are with the rhythm and how you vary the shape of the line, the more interesting your solo becomes. Here, I included examples of both diatonic and chromatic planing.

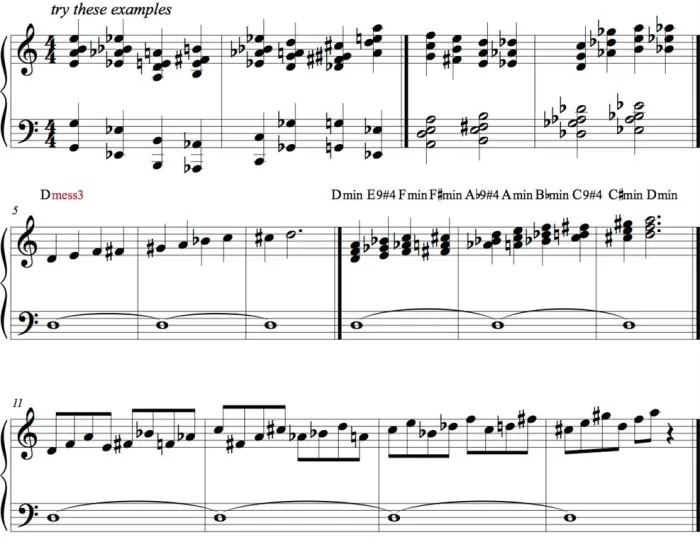

5. Advanced planing

In Ex. 5, I show more options on how to take planing to the next level. The first two examples demonstrate how you can put a desired sound in either hand and it sounds great regardless. Next I include a diatonic example of Messiaen’s third mode in a chord motion and as a linear manifestation as well.

“Most jazz pianists, in addition to studying things like bebop lines and standard chord progressions, have some experience with planing. Renowned pianists like McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, and countless others have explored this technique in depth,” says jazz pianist, composer, and educator George Colligan. A sought-after jazz sideman for over two decades, Colligan currently leads his own groups and tours with renowned drummer Jack DeJohnette. He is also Jazz Area Coordinator at Portland State University in Oregon. Colligan’s latest album The Endless Mysteries is out now.

"Despite its size, it delivers impressive audio quality and premium functions as well as featuring a good selection of inspired sounds": Roland GO:Piano 88PX review

MusicRadar deals of the week: Enjoy a mind-blowing $600 off a full-fat Gibson Les Paul, £500 off Kirk Hammett's Epiphone Greeny, and so much more