The beginner’s guide to music scales: what are they and why are they important?

Master the different types of scale and you’ll always hit the right notes

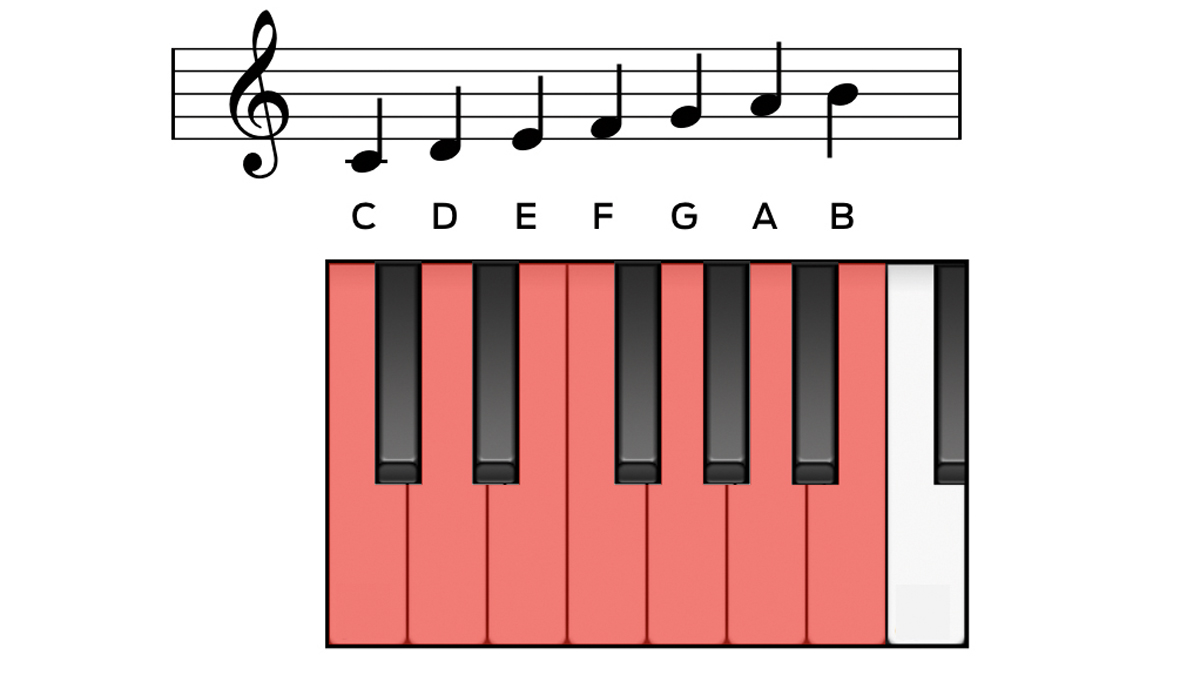

The basic definition of a scale is a set of musical notes arranged in order. Most people are familiar with the C major scale as being the one where you start at middle C on the piano and just play all the white keys up the keyboard until you’ve covered the notes C, D, E, F, G, A and B, eventually hitting C again an octave above where you started.

This is usually the first scale we learn, but there are different types of scale, each with their own individual sound, some containing different numbers of notes. They sound so different due to the variations in patterns of intervals between notes in each scale.

With 12 starting notes to choose from, and numerous patterns for each one, this gives rise to a dizzying number of scales to commit to memory. So why do theory practitioners place so much emphasis on learning them?

Aside from the physical benefits of practising them, the main reason to know a scale or two is that it gives you more of an idea of what notes to actually play over any given chord sequence. If you know you’ve got a song or track in a particular key, knowing the notes in the parent scale of that key means that you’ve got much more chance of hitting a note that will work over the chords that make up the tune.

10 things that every music producer needs to know about chords

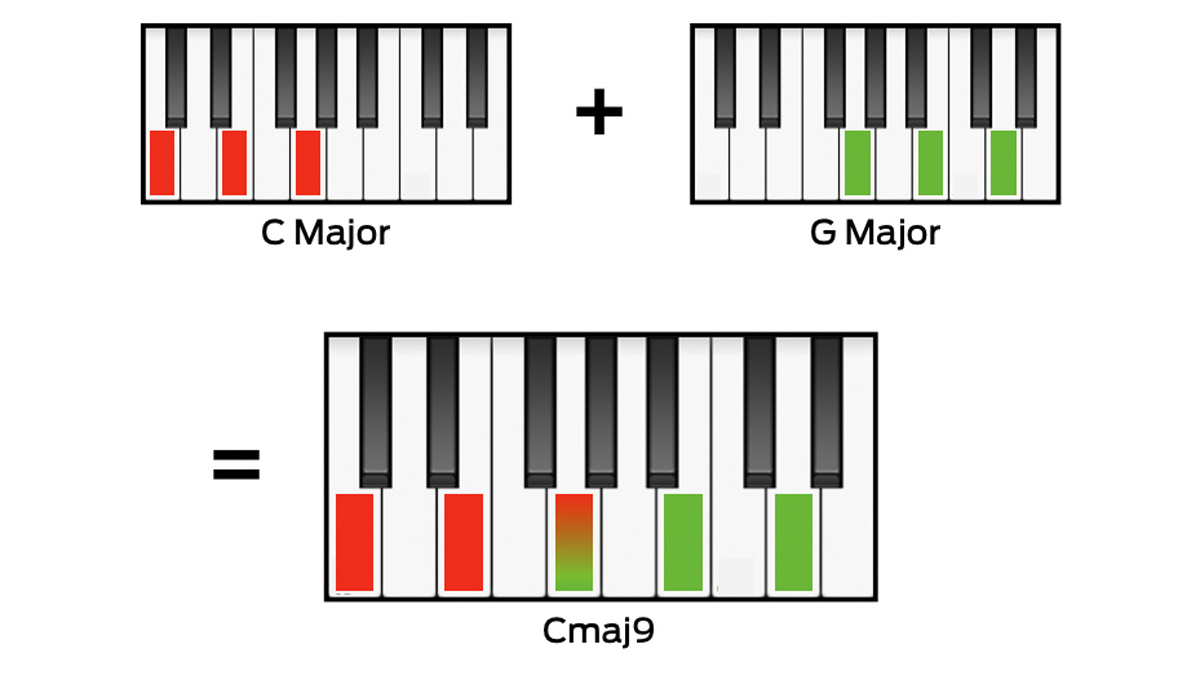

This is because, most of the time, in popular music, chord progressions are made up of chords that are diatonic to one key or another, and those chords will themselves have been built using the notes from the scale in question.

So, for example, if you know your song is in the key of A major, there’s a good chance that if you play the notes of the A major scale over the chord progression, you’ll get something musically palatable. So knowing your scales gets you off to a solid start when coming up with vocal melodies, lead lines, basslines and solos that actually work.

Common types of scale

Chromatic

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

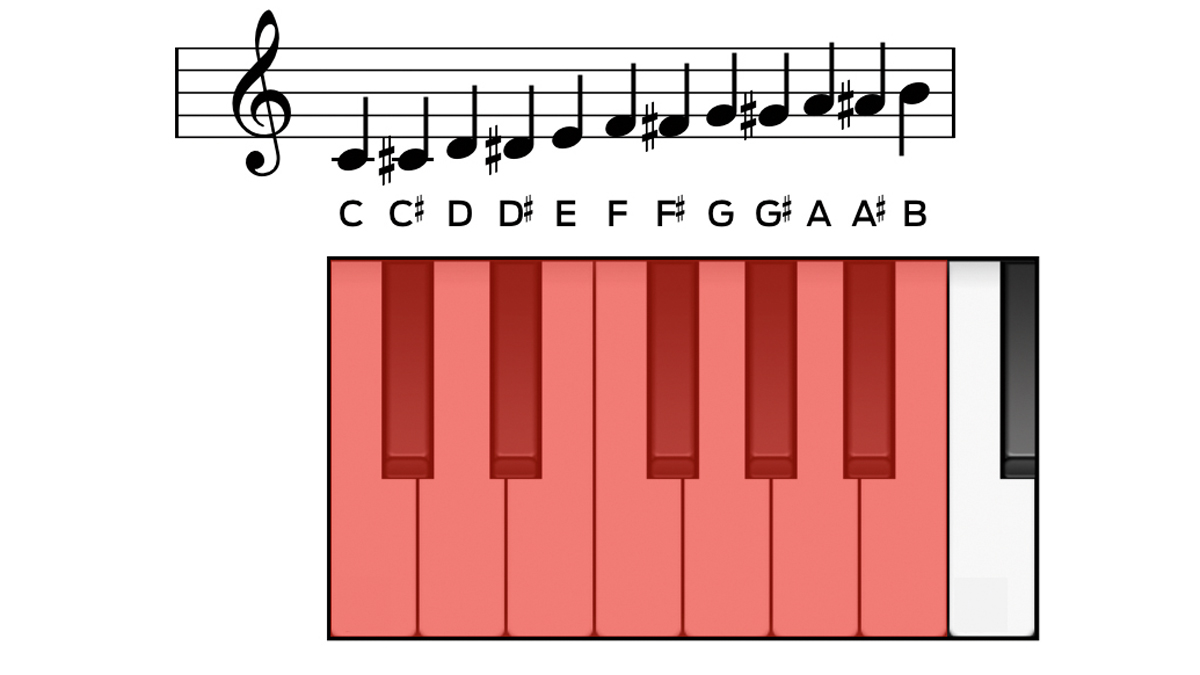

Taking in all 12 notes found within an octave, the chromatic scale isn’t generally used a great deal other than as a collection of every note you can possibly play on the keyboard, so it’s more useful as a teaching and practice aid rather than a practical scale to be used in your tracks.

Major

The major scale is usually the first one we learn, chiefly because it has a cheerful, happy demeanour and is one of the easiest scales to memorise and play. If you start on a C and play the seven white keys to the right in sequence, you’ll get a C major scale – C D E F G A B.

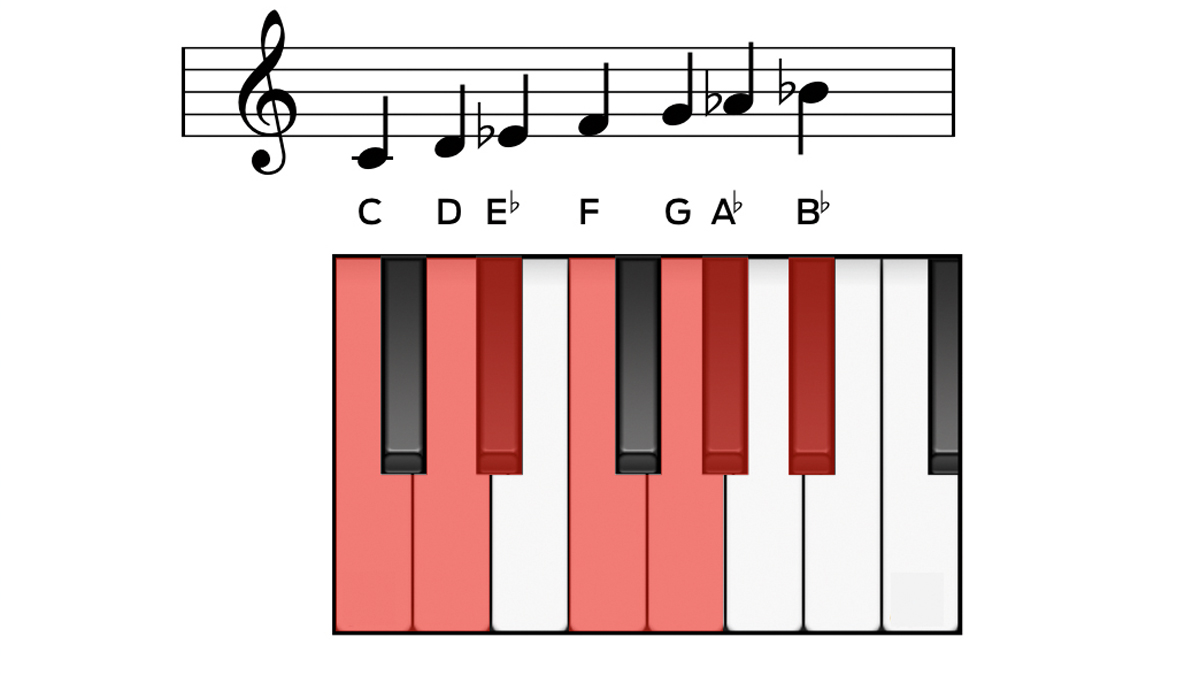

Natural minor

If you play a major scale from the sixth note in the sequence, the interval pattern produces the natural minor scale, which sounds darker and moodier than its major cousin. So with the 6th degree of C major being A, we get A B C D E F G - A natural minor. C natural minor would therefore be C D Eb F G Ab Bb.

Major pentatonic

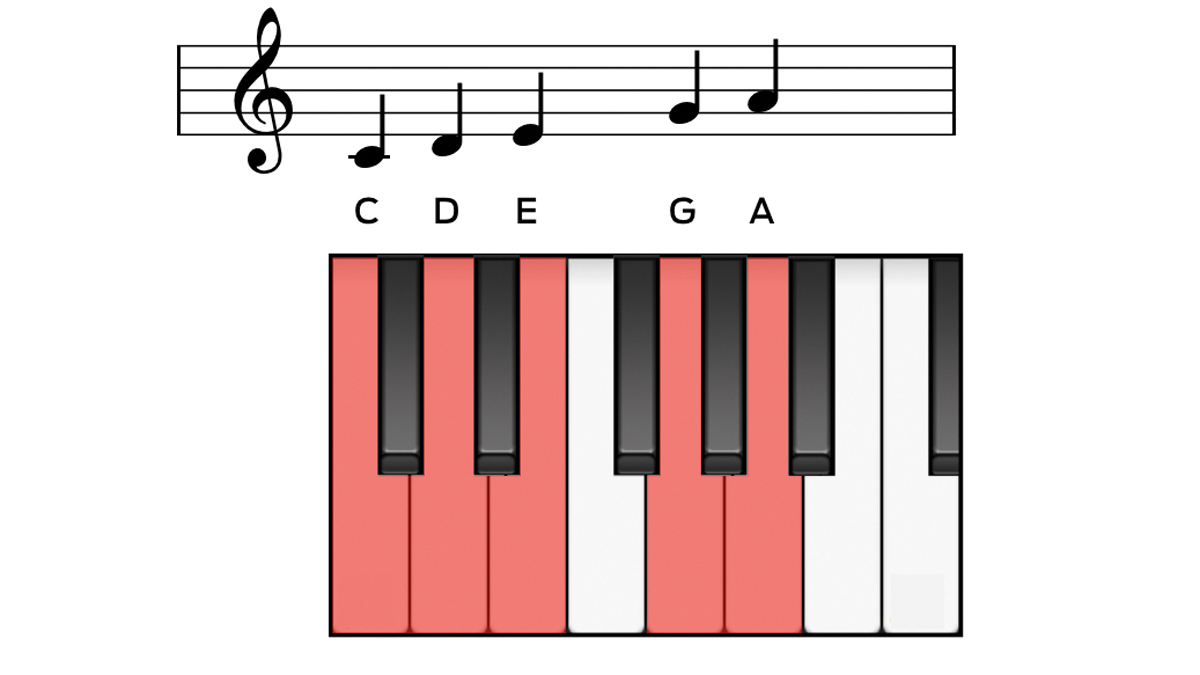

While major and minor scales have seven notes, pentatonic scales have only five. Essentially a major scale minus the 4th and 7th – C D E G A – the major pentatonic is a staple of folk, blues, rock and country, as it uses the five notes from a major scale that work over the largest number of underlying chords.

Minor pentatonic

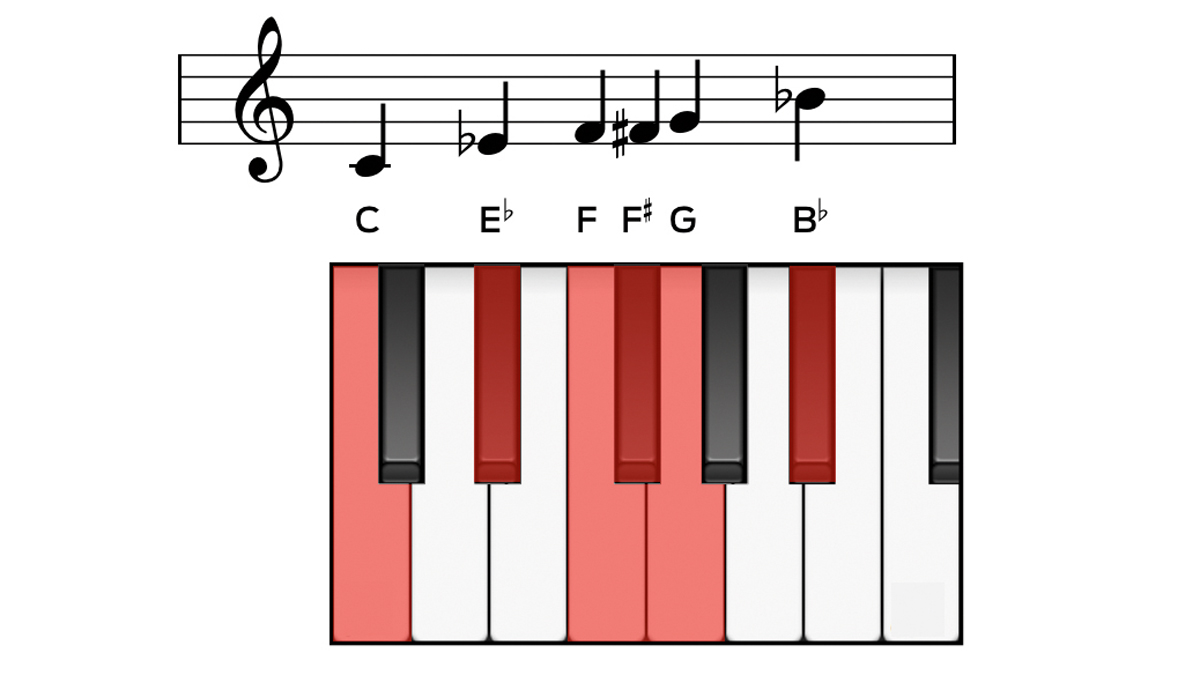

The minor version of the pentatonic scale is formed in a similar way to its major cousin, but by omitting two notes from the natural minor scale. The missing two notes in a minor pentatonic are the second and sixth degrees, so C minor pentatonic would be spelled C Eb F G Bb.

Blues

Take a minor pentatonic scale and add an extra note - the sharpened 4th degree - to get the blues scale. The C blues scale, therefore, goes C Eb F F# G Bb. Although you can play a standard minor pentatonic over the blues, adding that extra sharpened 4th gives it that essential flavour so characteristic of blues.

Scale tips

Intervallic formulae

Keyboard players are at a disadvantage to guitarists when it comes to memorising scales. The latter only have to memorise one shape for a scale, then move that shape up the neck to play it in a different key, whereas on the keyboard, playing the same scale up just one semitone requires having to remember a completely different pattern of keys. Play a C major scale, then a C# major one, and you’ll get the idea.

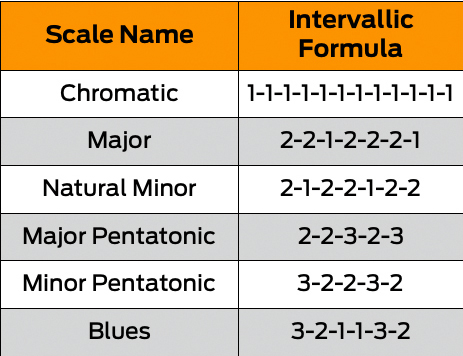

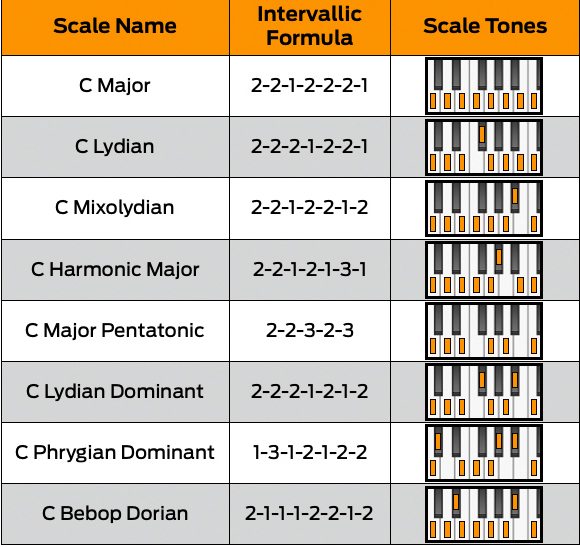

Rather than spending hours practising them until muscle memory takes over, you can remember simple number sequences - known as intervallic formulae - to help you work scales out on the fly, based on counting the number of semitones between each note in the scale.

For example, the formula for a major scale is 2-2-1-2-2-2-1, so to play, say, D major, you’d start on D, move up two semitones to E, then another two to F# , then one semitone up to G, two more to A and so on, following the formula to complete the scale.

The scale of your dreams

Scoring a dream sequence? Use a whole tone scale! The whole tone scale is a bit special as there are only two possible versions of it, depending on whether you’re starting on a white or a black key.

Whole tone scales are hexatonic, which means that they contain six notes, all separated by intervals of a whole tone - hence you get the name. With a formula of 2-2-2-2-2-2, wherever you start from on the keyboard, there are only two possible versions, and they work really well over augmented and dominant 7b5 chords.

Relative vs Parallel

Relative and parallel scales are often mistaken for each other, as they’re pretty similar- sounding. So what’s the difference?

Well, relative scales are two scales - one major, the other minor - that contain the same notes but start on different notes. For example, C major, which contains the notes C D E F G A and B, and A minor, which contains A B C D E F and G. Parallel scales, meanwhile, are two scales - one major, one minor – that start on the same note, such as C major and C minor.

Scale quantising

If all this learning makes your head hurt, and you want to ‘cheat’ a bit, you can use a MIDI transformer like AutoTheory or an iOS app like ThumbJam. Software tools like this only allow you to play the notes from a pre-selected scale of your choosing.

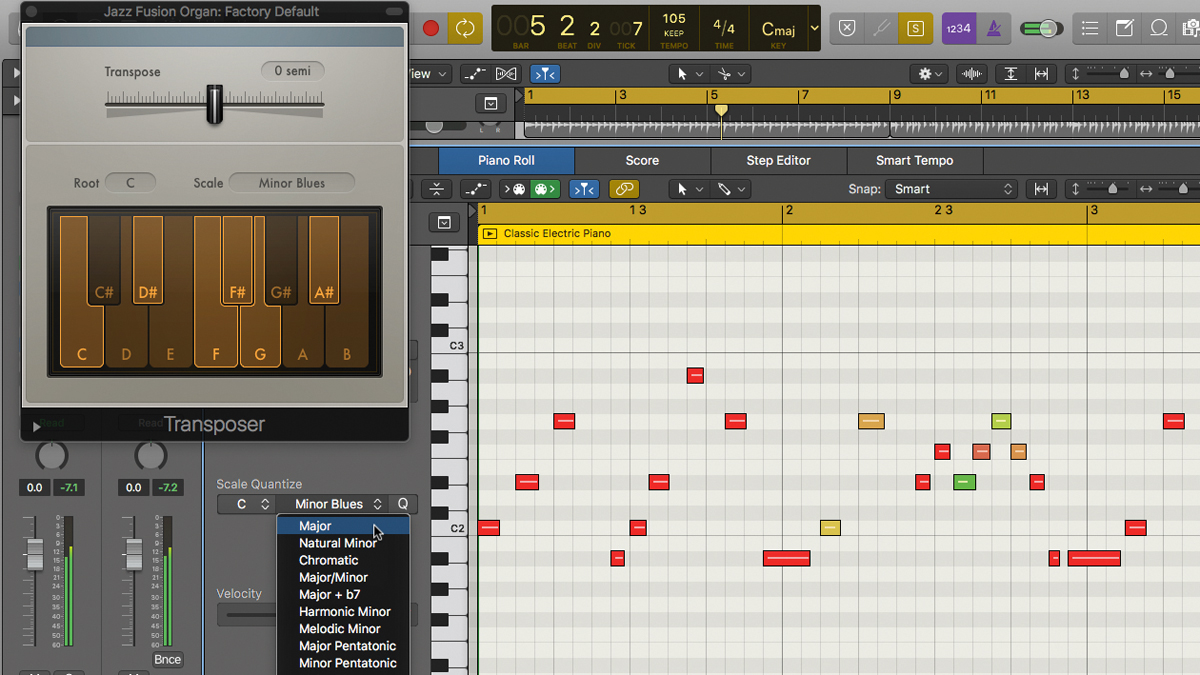

Some DAWs actually have this feature built in already. Logic Pro, for example, contains a scale quantise feature that shifts any wrongly-played notes to the nearest correct note in the chosen scale - handy indeed.

Many hardware controllers also feature similar approaches: NI Maschine, Ableton Push and Novation Circuit, for instance, all feature scale modes that lay out only the notes in the specified key across a grid of illuminated pads. And if you get the key and scale settings right, just flailing around randomly on the keys or pads can produce unexpectedly cool results you wouldn’t ordinarily have used, even if you already know your scales anyway!

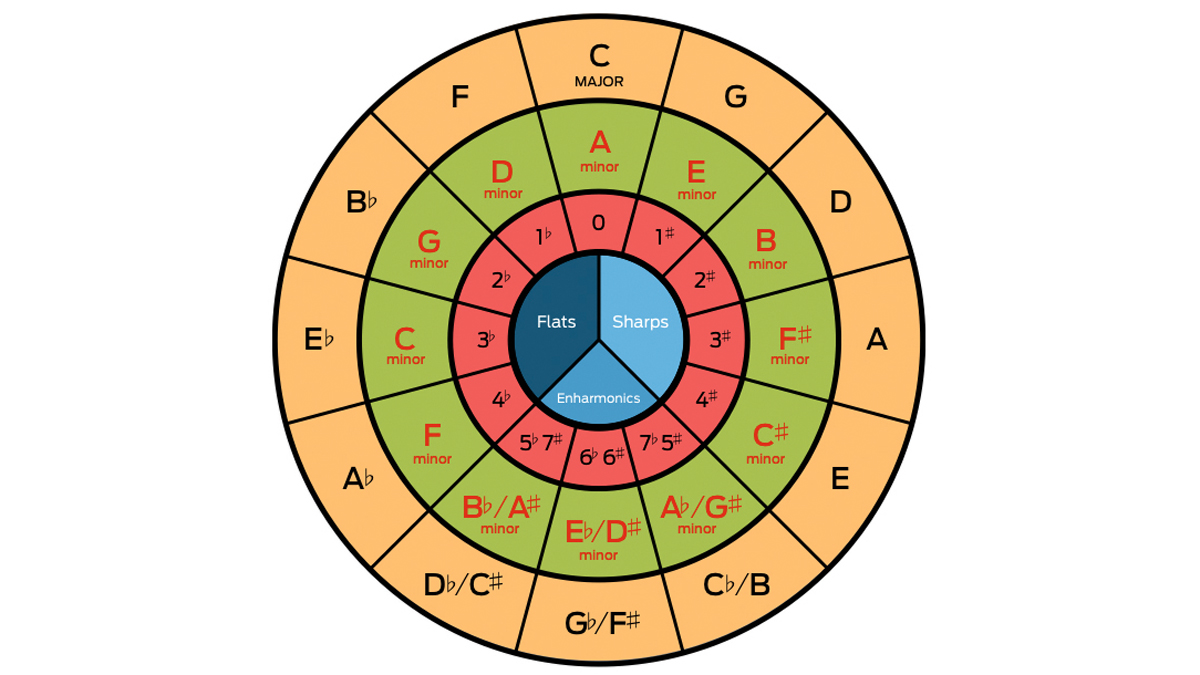

What is the circle of fifths, and how can it help with your music theory?

Soloing tips

When improvising over a chord progression, knowledge of scales is handy, as the type of chord you play over governs the scale type you use to select your notes from.

The best solos take the chord changes into account - safest choices are the major/ minor pentatonics and blues scale, as they contain fewer notes and work over more chords. However, each chord type has a wide selection of scales to choose from that contain the notes of that chord - major chords alone can support at least eight types of scale (see diagram below), so the more scales you learn, the more you’ll know what keys to aim at.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.