How to blend sound design and score to create a modern cinematic soundtrack

The boundary between sound design and score has blurred in recent years, as melody and abstract sonics fuse to create today’s modern soundtracking norm

Once a strict division, now the musical score and the sound design of a film’s world has moved much closer together over the last few decades.

Directors and lead creatives increasingly generally seek a more holistic approach when considering the overall aural approach. Writing soundtrack cues which aren’t strictly musical, but tension-stoking or attention-grabbing events has now become standard practice for composers.

One of the most notable watershed moments in this stylistic trend was the infamous “BRAAAM” sound which first accompanied 2010’s Inception trailer (and appeared throughout its soundtrack). Now something of a byword for a style of hyper-cinematic trailer, Hans Zimmer’s deployment of ultra-sub bass and horn-like seismic events resonated deep within our senses.

It promised size, it promised spectacle and more importantly, it psychologically re-sold the notion of going to the cinema as not just checking out the latest flick on a bigger screen, but being part of a physically affecting, multisensory experience in which we could immerse ourselves.

Zimmer’s incorporation of electronic music techniques, processed instruments and more amorphous textures in his soundtracks has helped to popularise this mindset. The late Jóhann Jóhannsson’s soundtrack for 2016’s Arrival is another key example, fusing traditional woodwind with tape loops, heavily treated vocal effects and polyrhythms.

Jóhannsson’s score was written in close collaboration with the film’s editor, and worked as a conspicuous character within the communication-themed movie. He used fragments of melody and delicately mixed vocals that eventually coalesced to sonically reflect the film’s concept. To underscore the circular language patterns that the film’s aliens speak, Johan reverted to a tape-based approach.

“I have a 16-track analogue tape recorder […] and created a loop, rather a long tape loop, which I used to stack layers and layers of various instruments, like piano, without the attacks,” Jóhannsson told Consequence of Sound in 2016. “So we just recorded the tone of the piano, not the attacks.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Modern soundtracking of this type goes far beyond rustling up melodic themes. It requires the composer to anticipate the intended impact of the overall picture, and be more technically involved with the editor and director to lock cues tightly with each shot. Maximising the impact of both the underlying themes, and the atmosphere of the world.

Learning how to work in this way necessitates a lot of constraint too. Within dialogue-heavy scenes particularly, key lines might need some all-too-subtle emphasis, yet you need to be sure that the music you’re deploying doesn’t intrude in the frequency domain of the dialogue.

In practical terms, then, how can we transition our thinking to be able to tackle such a less musically oriented project? Firstly, it helps to experiment. Sound design is all about building new textures, and taking existing sounds and moulding them into new ones. To keep your sound original, sampling real world sounds is a great place to start.

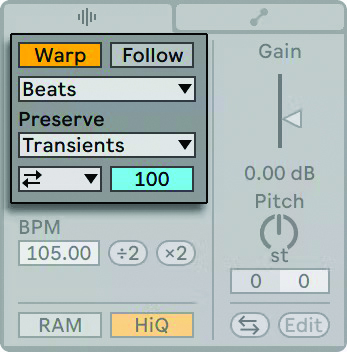

Using pitch-shifting and time-stretching plugins (such as Ableton Live’s Warp or Celemony’s Melodyne) you can contort these starting point sounds into characterful new shapes. Spatial effects, such as reverb, echo and delay can give both size and resonance to your sounds. As with mixing a standard track, spatial effects can be deployed to glue the more abstract sonics with the musical or melodic information that’s concurrently happening.

Movement can be key to your sounds feeling like an organic part of the world. Using LFOs and slow attack/decay envelopes to build ominous, rumbling pads can create a greater feeling of immersion. Boosting and cutting key frequencies in sync with the picture is another route to sonically reflect that the sound is responding to the events on-screen.

Using these kinds of approaches, you can start generating abstract sounds and malleable texture to play with. While it’s exhilarating to jump down creative rabbit holes, an eye must also be kept on the usability of this growing repository. You don’t want to be dealing exclusively in attention dominating, hyper-loud cues.

You need variety, and more often than not, you need subtlety. More static atmospheres are something which all filmmakers (and TV show and video game composers) aim to convey quite frequently. Increasingly, it’s the sound design that plays the largest role here.

To prepare for these kinds of static atmosphere-reflecting challenges, it helps to get in the habit of crafting tracks that are designed to evoke particular environments. Think of all those animated, off-the-peg synth presets that are labelled with such monickers as ‘Sad Cityscape’ or ‘Scorching Desert’.

Wouldn’t it be nice to have your own unique batch of sounds, ready to be called up as a starting point? With those types of locations in mind, having a stab at writing several three to four-minute pieces that are intended to evoke a certain geographical aesthetic is a top exercise for budding cinematic sound designers.

The fusion of soundtrack and sound design has undoubtedly heightened the experience of watching a film. While there’s still much to be said for a compelling melody or magical theme, music now exists within a much more organic and all-encompassing sonic universe, being just one of many elements that work to place the audience in the same physical or emotional space as the visuals.

Pad principles

Subtlety goes a long way. Often, you might want to suggest musicality, without writing anything too kinetic. Ambient pads are a solid way of colouring your soundscape and bridging the landscape of the visuals with the score’s musical groundwork. Typically, ambient pads typically are constructed using a gradual attack times, long sustains and a slow release so that the sound gently fades into the ether.

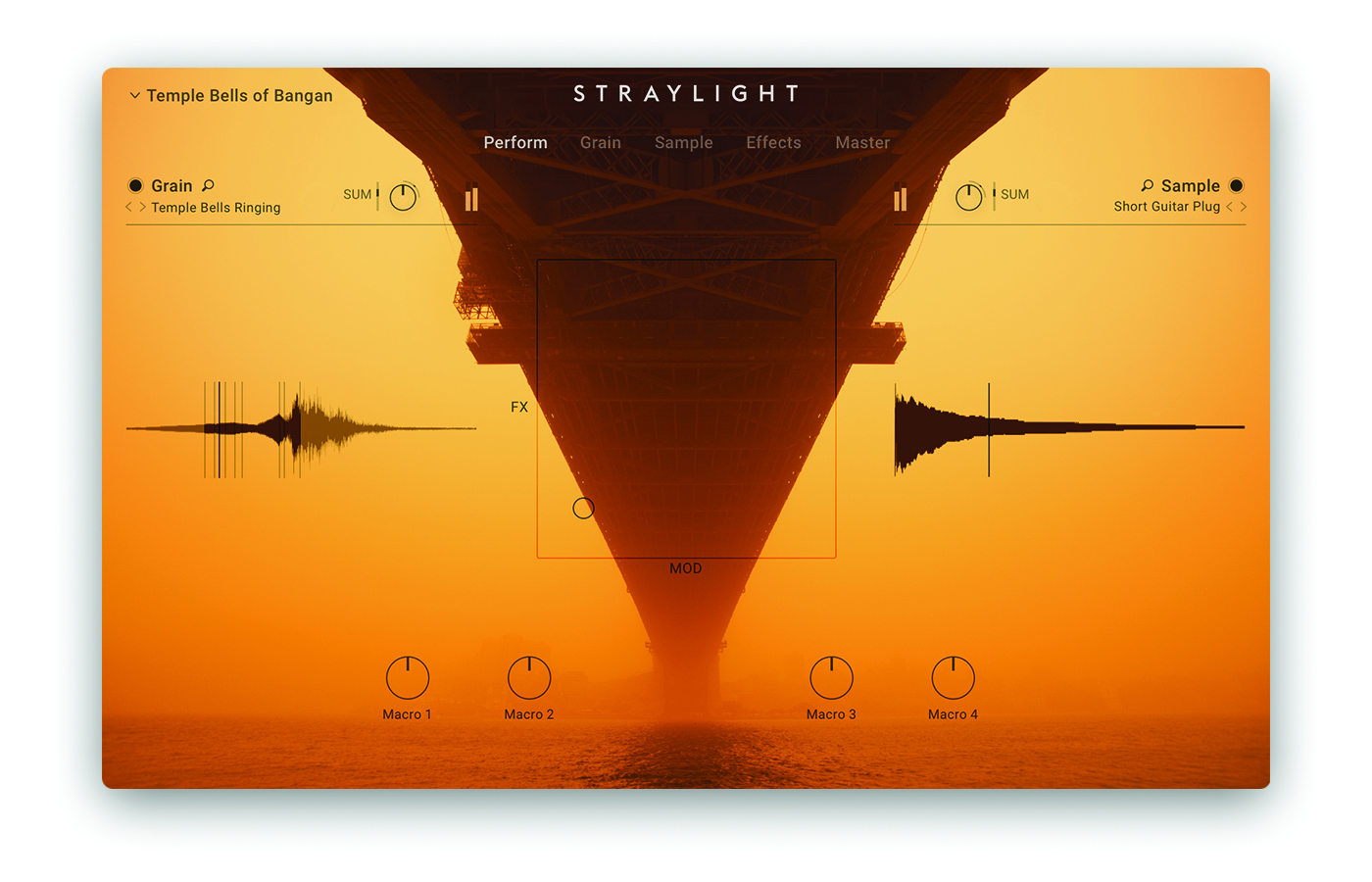

Beyond reverb and delay (which are something of a given when dealing in pads) small amounts of modulation such as layered noise, filters (particularly high-pass) that slowly open and close as well as quiet, subtle arpeggios can add the right amount of underpinning throb and texture that might do wonders when sonically representing a starship bridge or control room, as well as direct the musicality of any incoming melodic cues.

If things still sound a little flat, then adding some vibrato by modulating the pitch of one of your oscillators can really bring some life to proceedings, and better reflects a live instrument. In a mix context, you’ll want the pad to span the stereo image. Panning each voice to different stereo channels is a quick route to building the illusion of scope.

I'm the Music-Making Editor of MusicRadar, and I am keen to explore the stories that affect all music-makers - whether they're just starting or are at an advanced level. I write, commission and edit content around the wider world of music creation, as well as penning deep-dives into the essentials of production, genre and theory. As the former editor of Computer Music, I aim to bring the same knowledge and experience that underpinned that magazine to the editorial I write, but I'm very eager to engage with new and emerging writers to cover the topics that resonate with them. My career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website, consulting on SEO/editorial practice and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut. When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.