Songwriting basics: how to use repetition and variation to create melodic hooks

Repeating phrases doesn’t always make a song boring - in fact, the opposite can be true

Like it or not, repetition is a vital ingredient in music, especially pop. We’re not necessarily talking about the kind of relentless hammering of a chorus hook that makes your parents mutter darkly - annoying parents has been, after all, one of the main remits of pop all along. No, the kind of repetition here is more to do with individual notes, or pairs - specifically using repeated phrases or motifs to build melodic hooks.

The main idea behind repeating elements in your music, be it individual notes, small groups of notes or even complete hooks, is to fix the tune firmly in your listener’s ear, so that they both expect it when it happens again, and remember it once it’s over. It’s all part of the ‘singalongability’ factor that’s an essential component of any successful hit.

All that said, mere repetition alone runs the risk of proving our parents right and becoming a bit boring. We can combat this by adding slight variations to the repeats, combining the best of both worlds and hopefully ending up with a hooky, memorable tune.

So if you ever find yourself stuck for a melody to fit over some chords, the technique shown in our walkthrough here could be a great way to produce the sort of earworm melody that should stick in your audience’s mind both during and after the song.

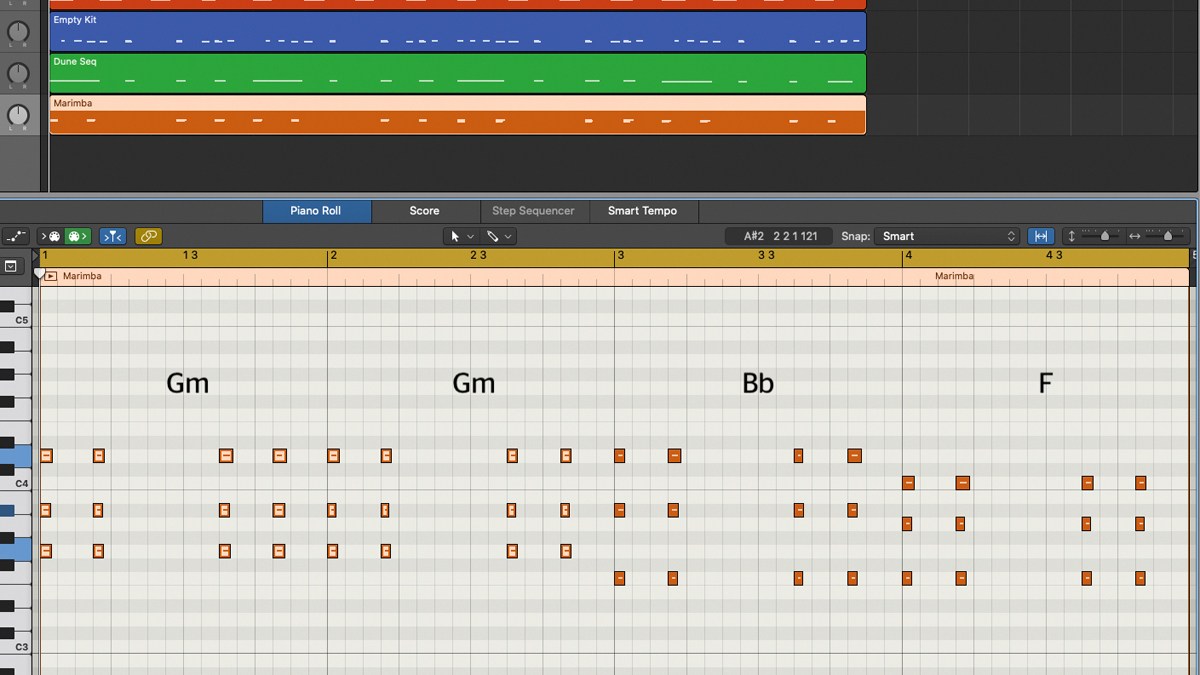

Step 1: Here we have a track made up of a four-bar progression with a rhythm track and chords already established, so we’re going to try to come up with a suitable melody to go on top. The chords are Gm > Gm > Bb > F, and those repeated Gm chords sound very much like ‘home’, suggesting a i > i > III > VII progression in the key of G minor.

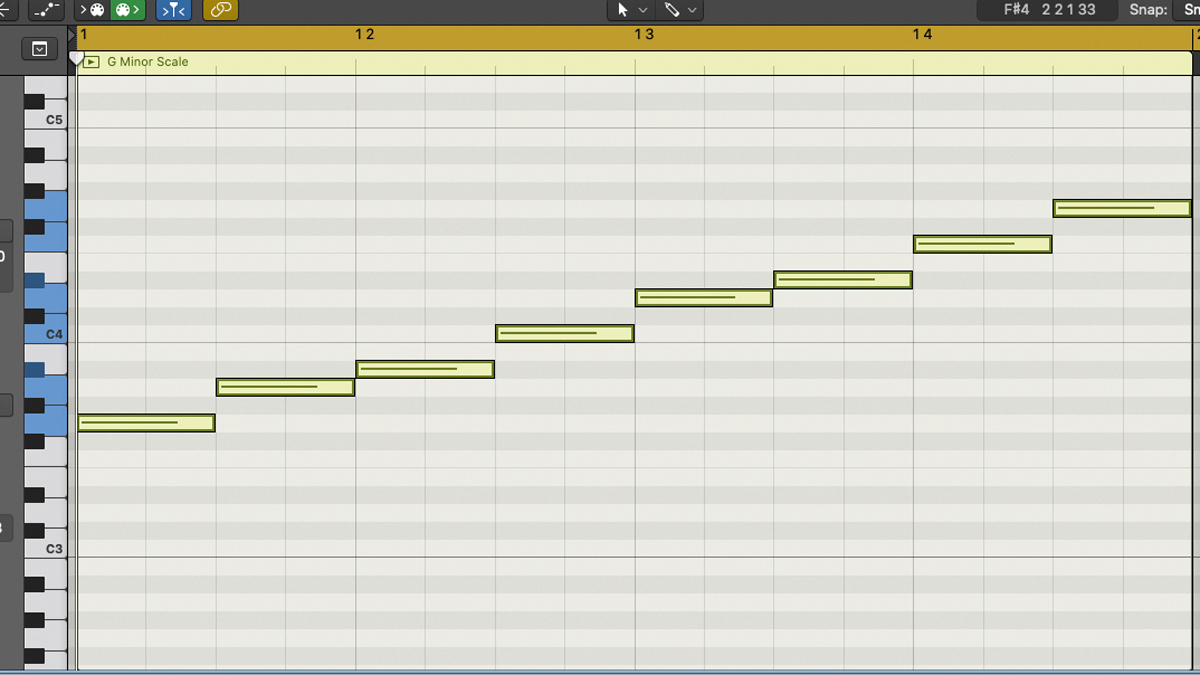

Step 2: Since we’re assuming we’re in the key of G minor, and all the chords are diatonic to (belong to) this key, it follows that any melody notes taken from the G minor scale should work over our chord progression. So that gives us a palette of G, A, Bb, C, D, Eb and F to choose our melody notes from, with G as our root note, or tonic.

Step 3: We’ll build our first melodic building block by alternating between two notes, but which? We could choose any, but the fifth degree of the scale is known as the dominant, and has a strong feeling of wanting to resolve back to the tonic. So having this persist would prolong tension nicely for having our melody resolve back to the tonic at the end of the phrase.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Step 4: For the second alternating note in our pair, we’ll go for the fourth note in the scale, which is known as the subdominant because it’s one scale step below the dominant. So if we’re going for the fourth and fifth degrees of the G minor scale, that makes our target notes C and D.

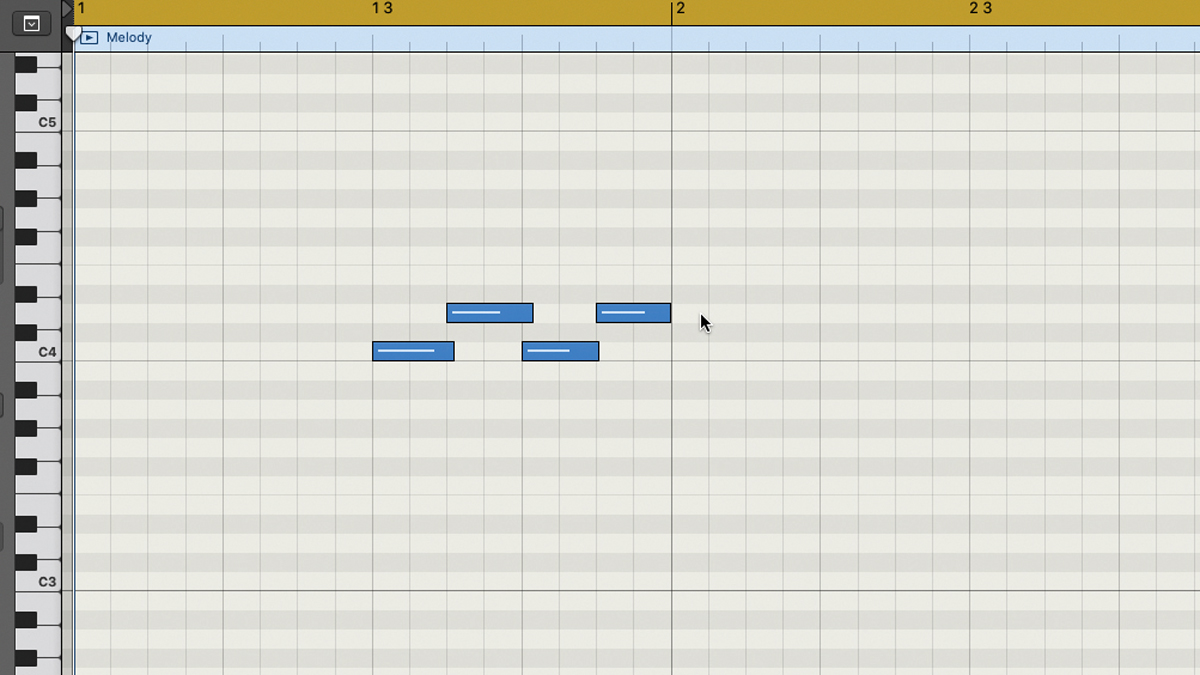

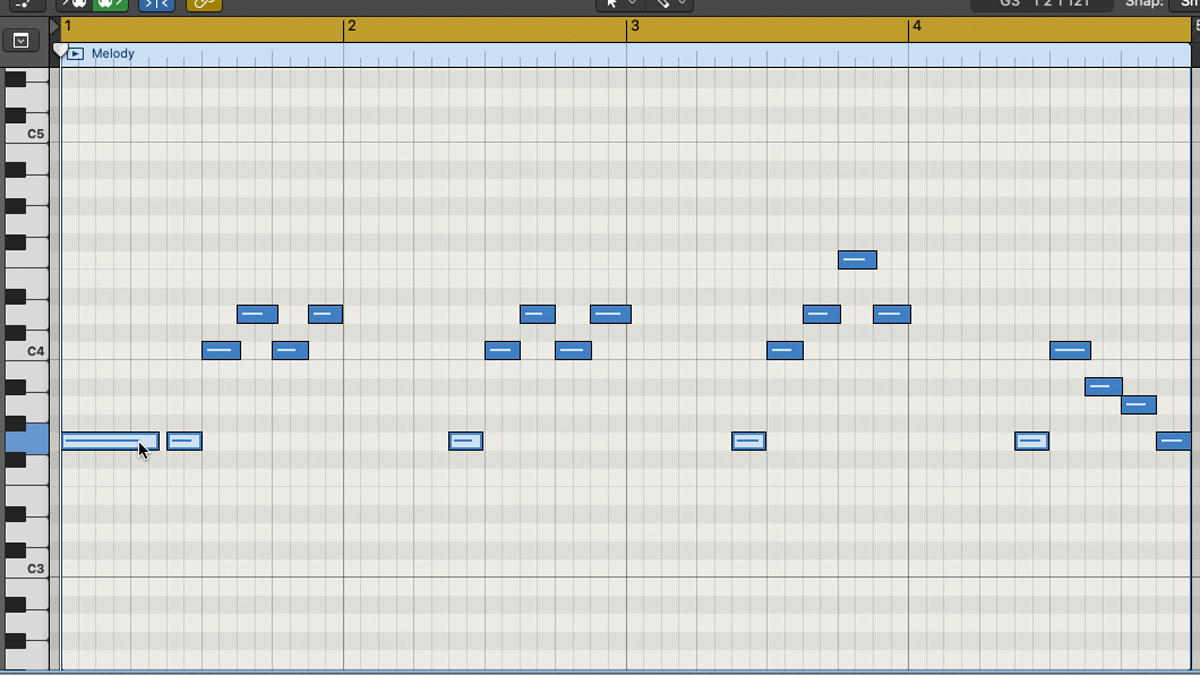

Step 5: So now let’s create our first building block, or motif. Using eighth-notes, we alternate twice from C to D and back again, ending up with a simple, four-note motif - C-D-C-D - which we place on beat 3 of bar 1, so that the four eighth-notes fill the remaining two beats of the bar.

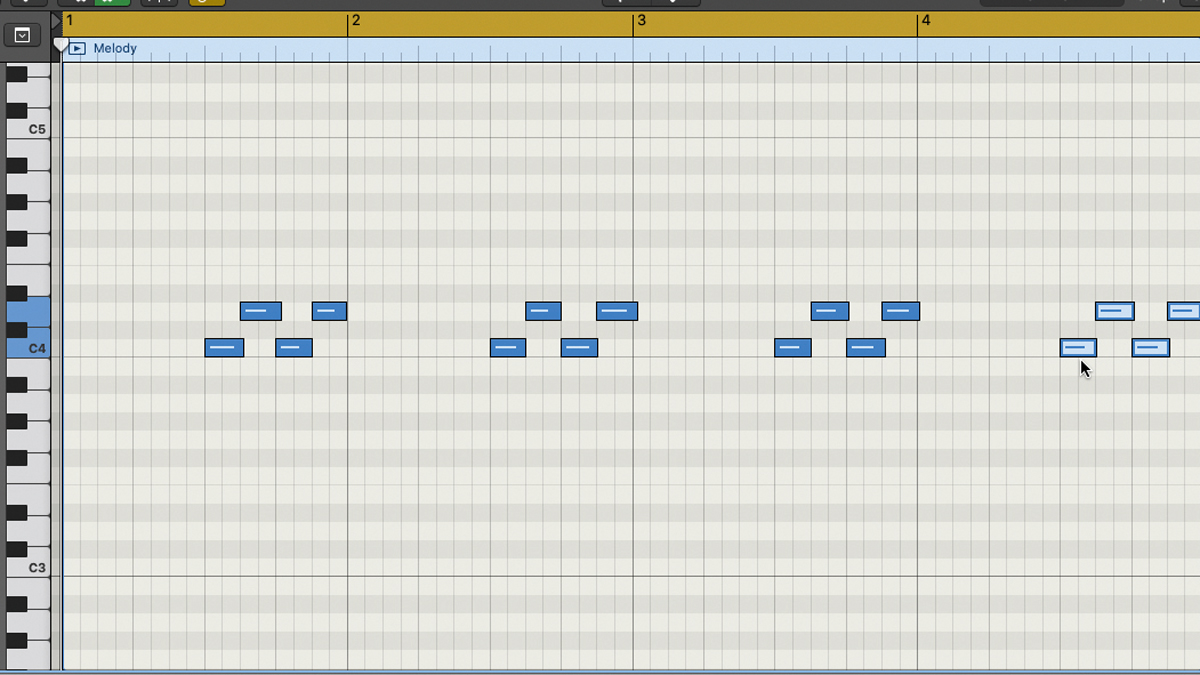

Step 6: Here another repetition comes in - we copy and paste the phrase into each of the remaining three bars, occupying the same position on beat three of each bar. Due to the fact that the chords in the progression are all diatonic to the key of Gm, and the notes in the melody are all taken from the parent Gm scale, it sounds OK - but we can do better!

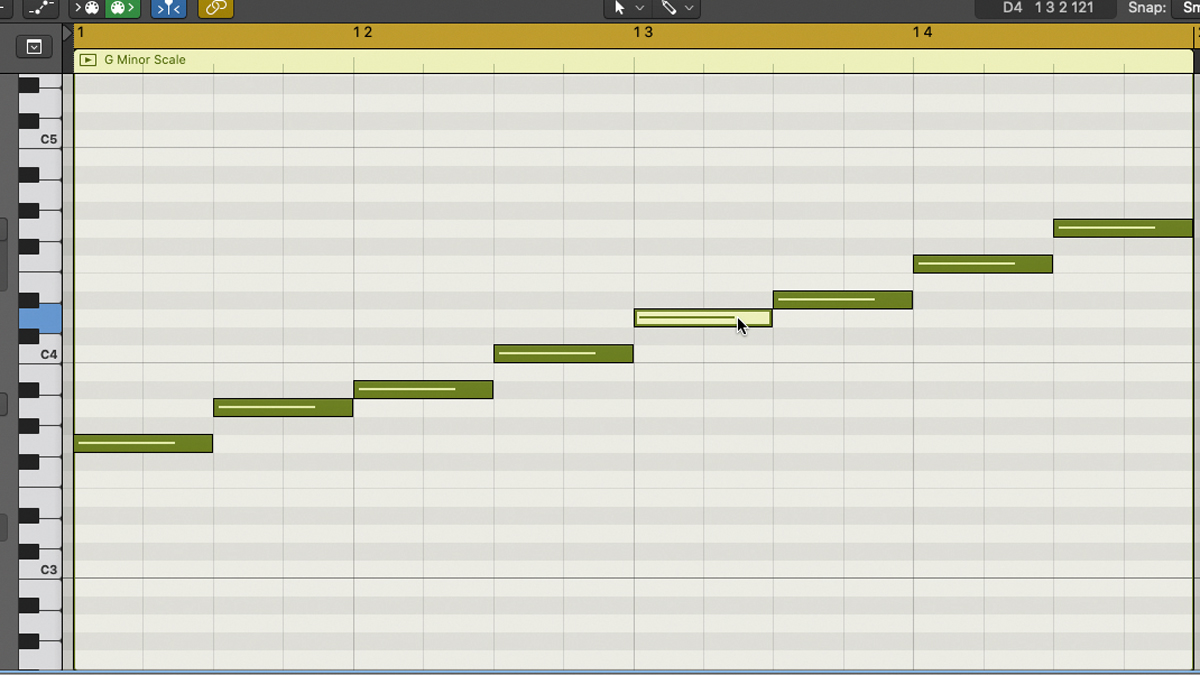

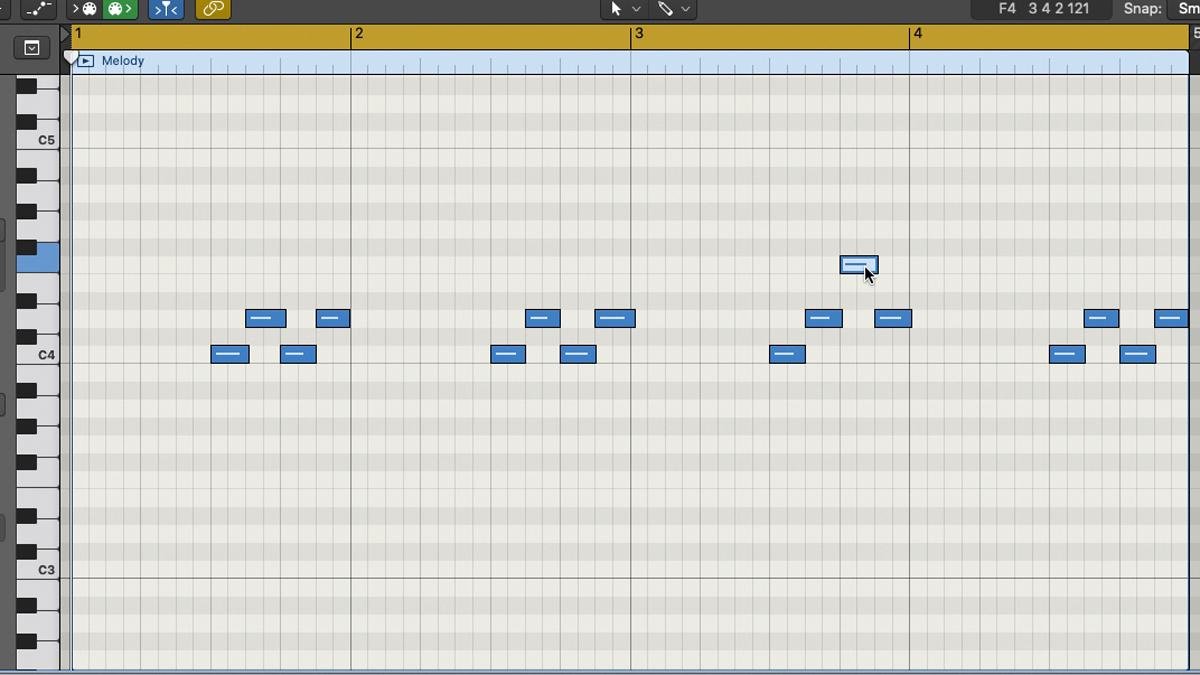

Step 7: Now we can make some variations. Starting off subtle, and leaving the first two phrases as they are because they’re both over the chord of Gm, we home in on the third repeated motif and change its third note from C to F. This note is a good choice as it’s also present in the underlying Bb chord (Bb, D, F).

Step 8: Next, we turn our attention to the last of the four repeated motifs. The aim is to resolve the tension provided by the repeated dominant note in the previous motifs and lead our audience back down to the tonic. So, keeping the rhythm the same, we simply step down the notes of the Gm scale from the fourth - C - through Bb, A and finally back to G.

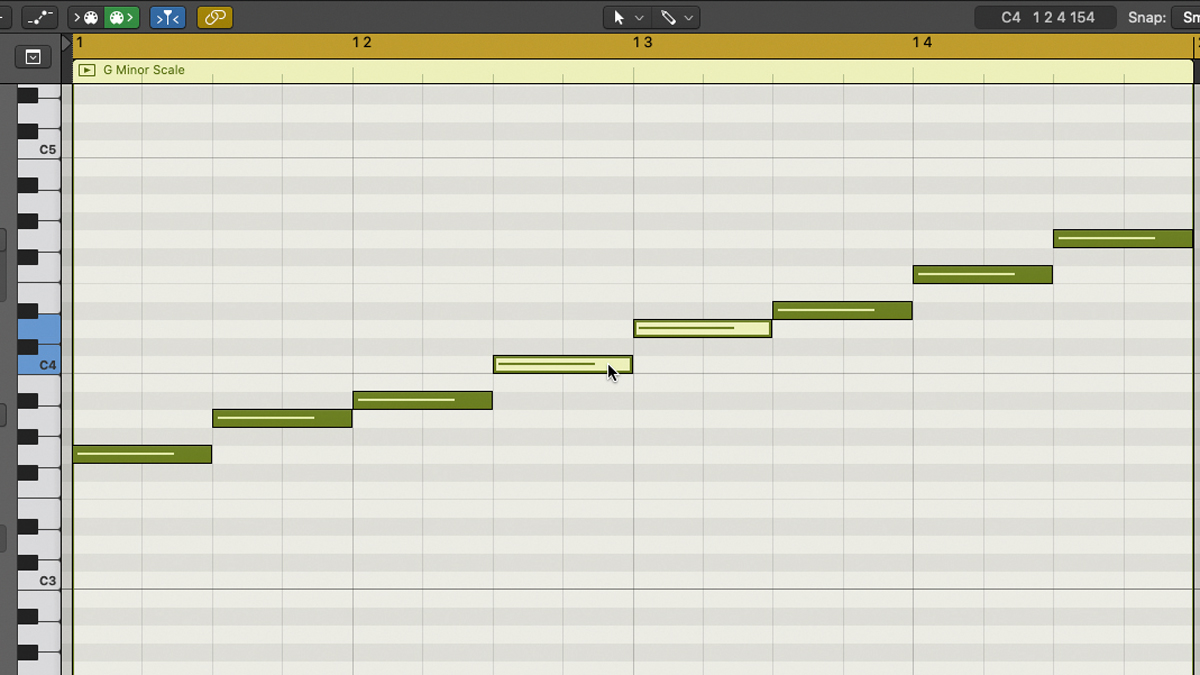

Step 9: This has done a lot to give the melody some shape, but we can take things even further by adding in some extra tonic G notes - one long note on the downbeat of bar 1, followed by an eighth note before the start of each of the four motifs. This makes each of the four phrases a little more complete and grounded by starting them off on the tonic note.

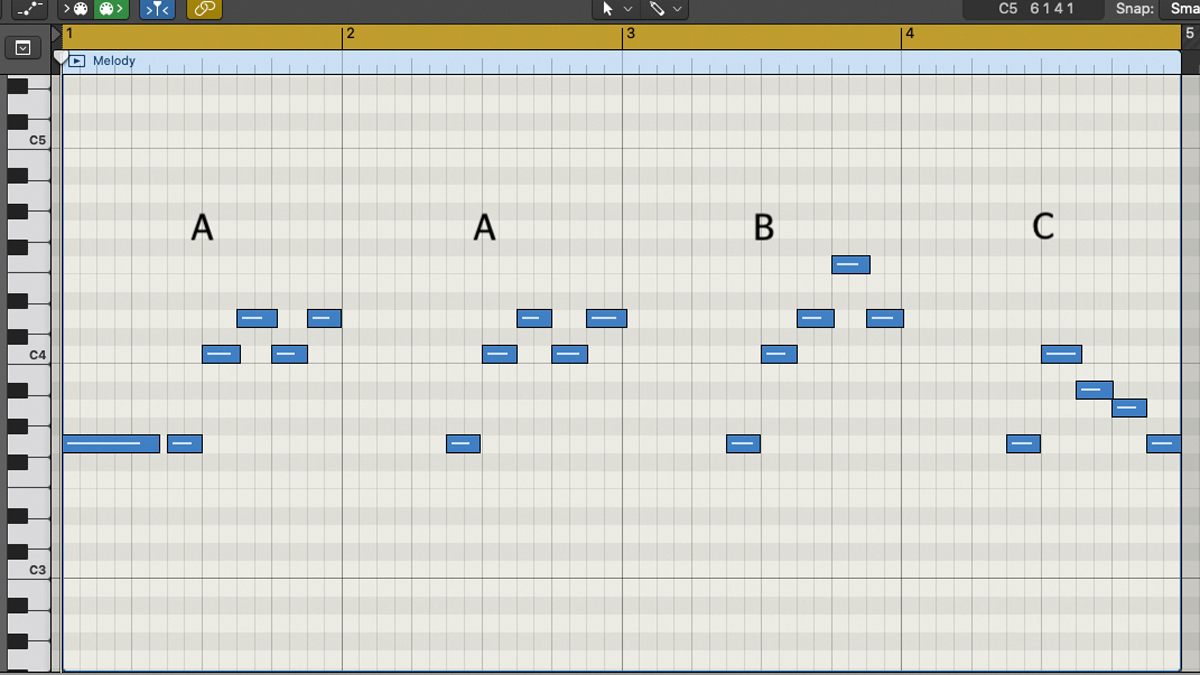

Step 10: Structure-wise, our melody is effectively split into four separate phrases, but since two of these - the first two - are the same phrase repeated, we currently only actually have three distinct motifs. So if we were to label each of these motifs A, B and C, the format of our melody as it is here could then be spelled out as A, A, B, C.

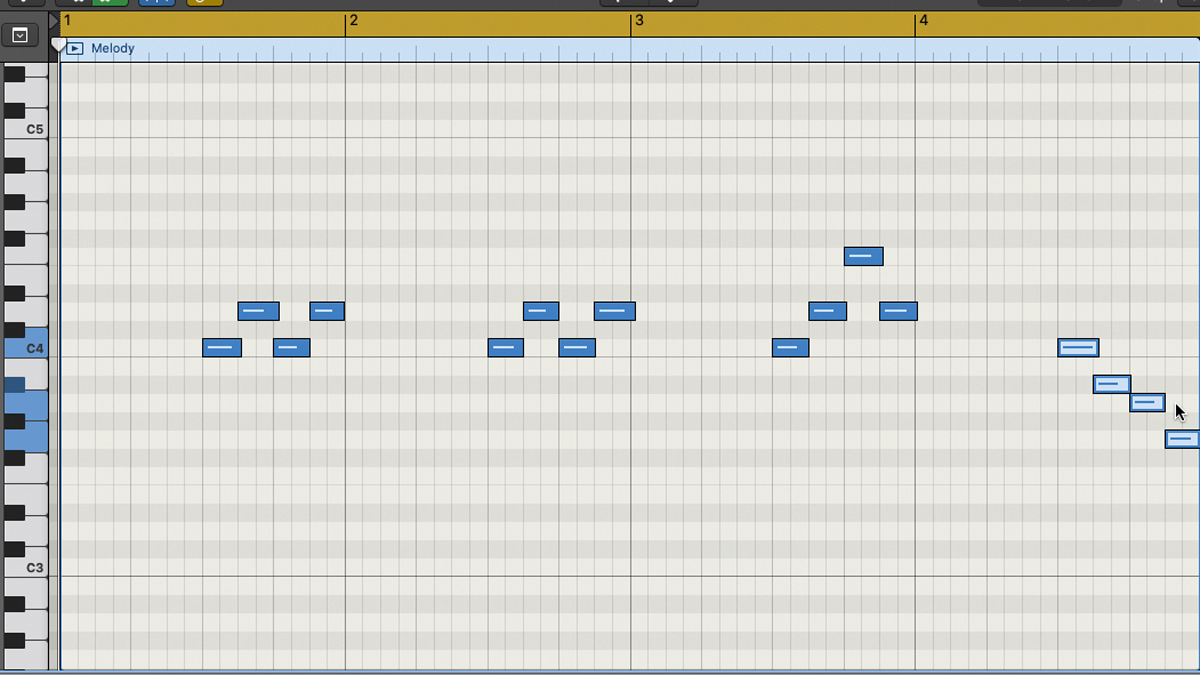

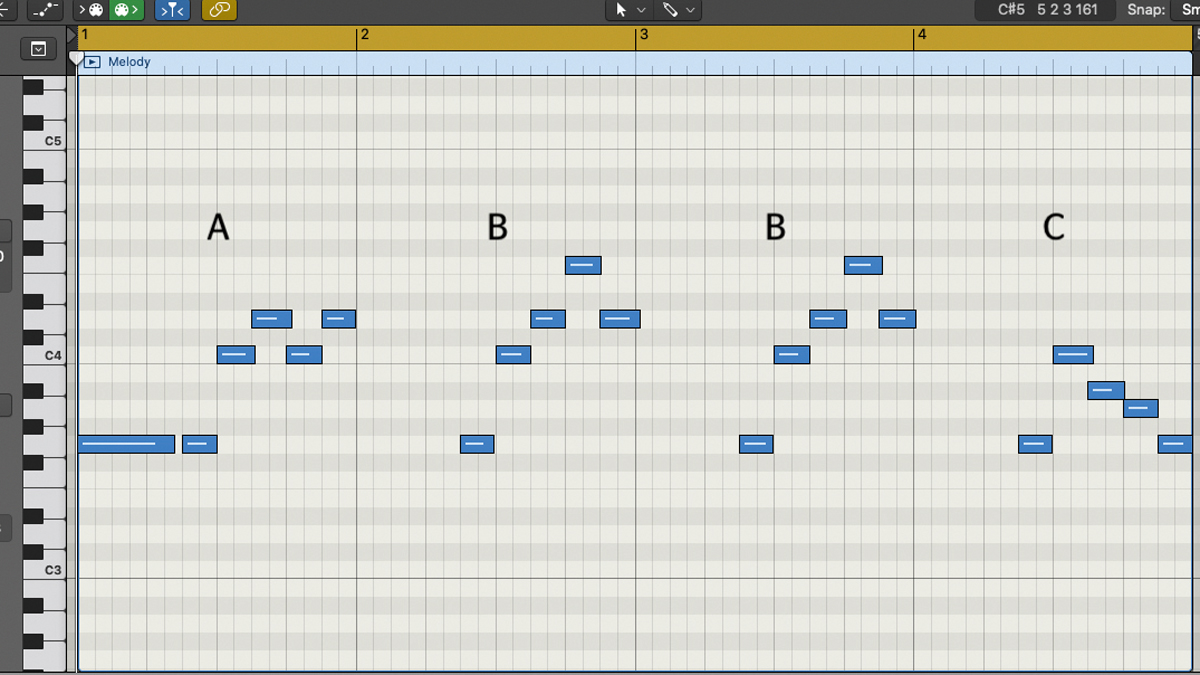

Step 11: Now that we have three to choose from, there’s ample scope to play around with the order of the motifs within our four-bar section. For example, we can change the order from A, A, B, C to A, B, B, C as an alternative option, by swapping the third phrase into the second slot.

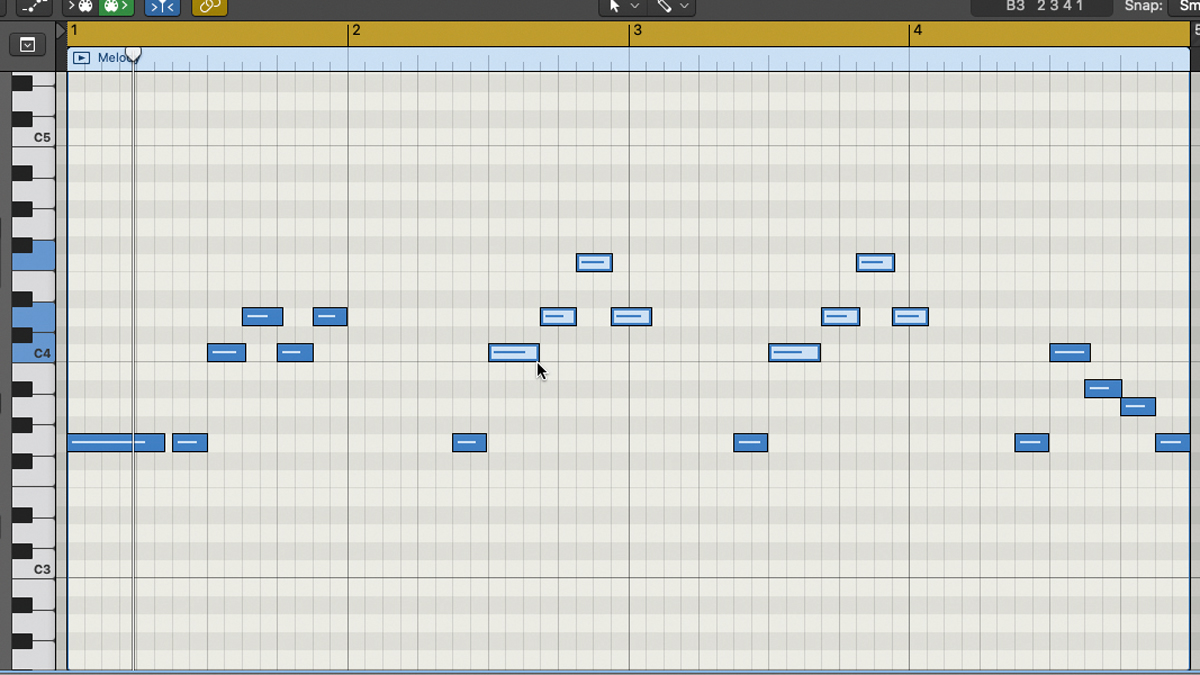

Step 12: As well as the melody, we can also introduce slight variations in the rhythm of each motif. For example, here we’ve homed in on the second and third motifs, lengthened the first C note of each one and shifted the following three notes one sixteenth-note later to produce a rhythmic variation.

Pro tips

Shape up

When coming up with memorable tunes, the overall shape can be an important consideration. The most memorable melodies often have a discernible arc to them, so when using repeated motifs as building blocks, try to introduce variations that create a shape.

For example, a verse melody might take on an arc suggestive of a takeoff, flight and landing, a pre-chorus might start low and build to a high point, while a chorus melody might simply just stay high.

We’re levitating

One inspiring example of repetition and variation is the verse melody from Dua Lipa’s Levitating. Over the course of the eight-bar verse, the main melody - a descending run down the B minor scale from the dominant (F#) to the tonic (B) - is repeated over four two-bar sections, but the third section is inverted so that it runs back up the scale from tonic to dominant. The final repeat resumes the original form, creating a neatly defined shape for the verse melody.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.