Songwriting basics: how diminished 7ths can spice up chord progressions

They're not as scary as they sound, and are an incredibly useful writing tool

Diminished seventh (or ‘dim7’ from here on out) chords are nowhere near as scary as they sound - once you know the formula for how to put them together, they’re pretty easy to suss.

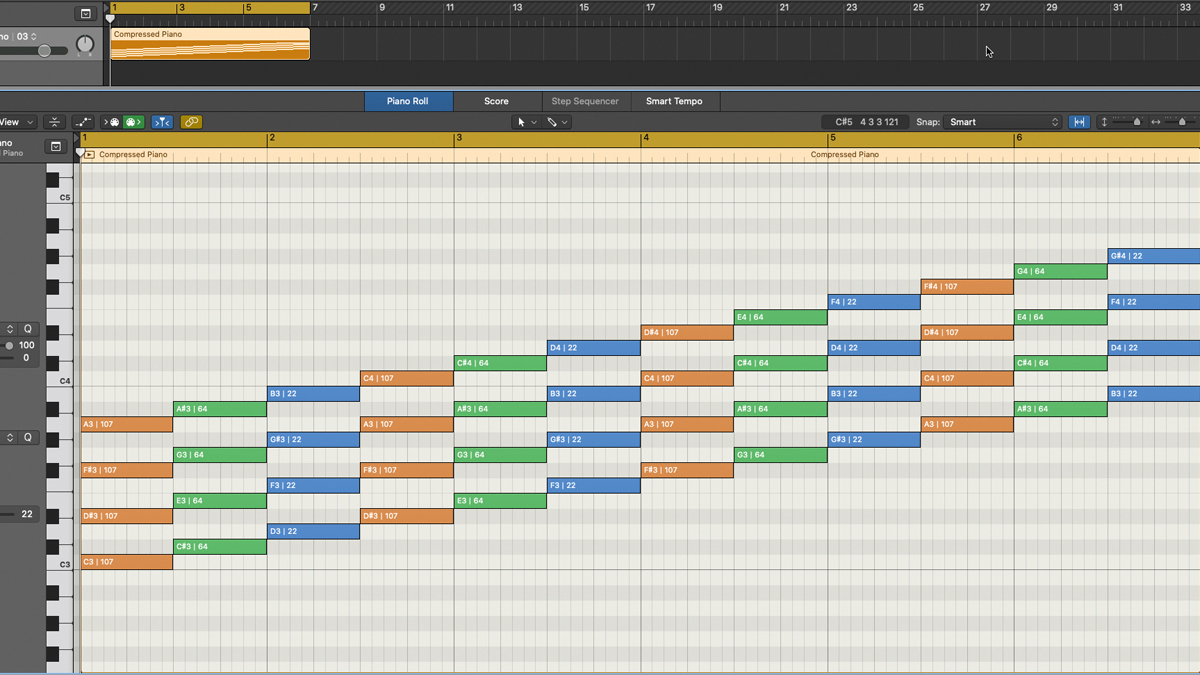

This is down to the unique, symmetrical way in which a dim7 is structured, with all four notes in the chord separated by the same pitch distance or interval - three semitones. This in turn means that, by shifting each of the three chord shapes up or down three semitones, you can cover four different chords with the same shape, each chord rooted on whichever note is at the bottom of the stack you’re currently playing. This way you can use the same three shapes to cover all 12 chords in the set.

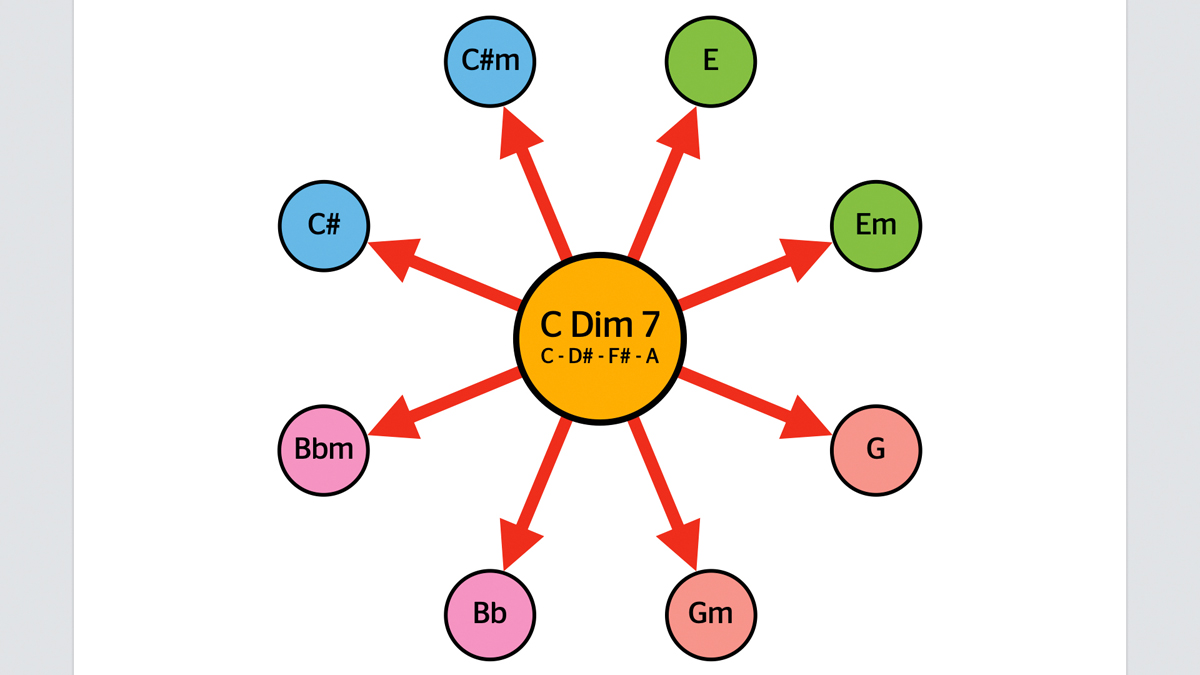

What makes the dim7 such a powerful songwriting tool is that, due to their symmetrical structure, they can resolve to a grand total of eight possible other chords.

This makes them perfect for squeezing in to act as harmonic links between chords to extend a progression, so they’re a great weapon to have to add a little splurge of extra professionalism to your tunes.

Here, we’ll show you how to build diminished seventh chords and then demonstrate a couple of examples of how to use them to add pep to some basic chord sequences.

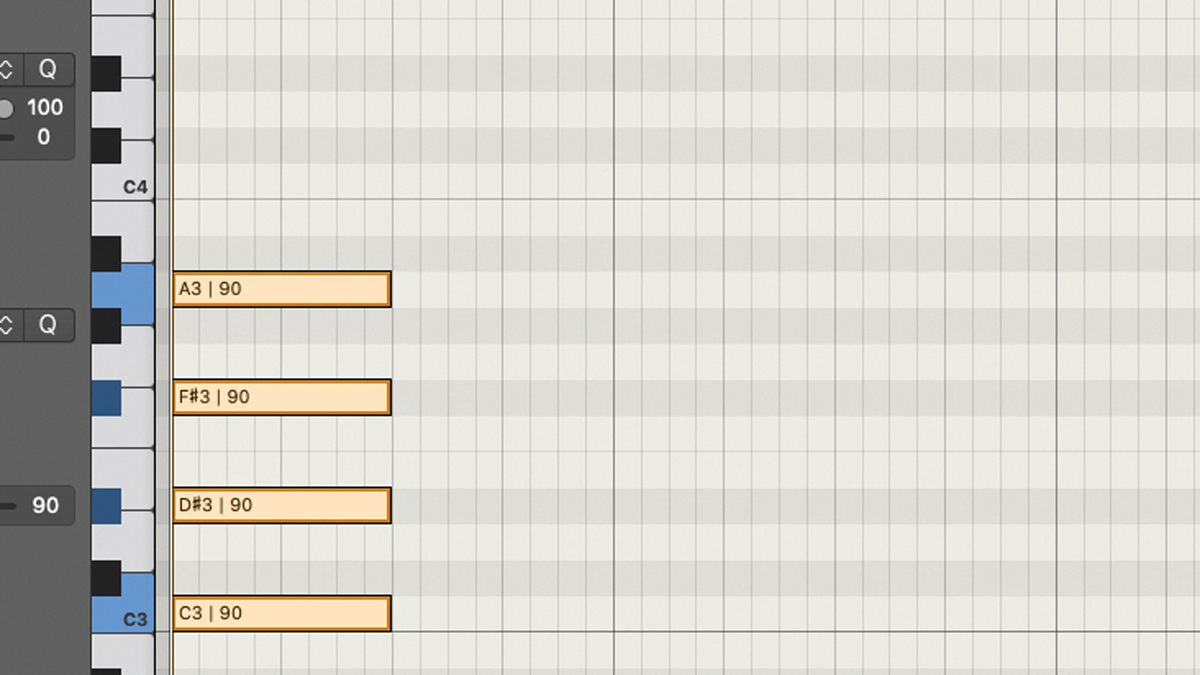

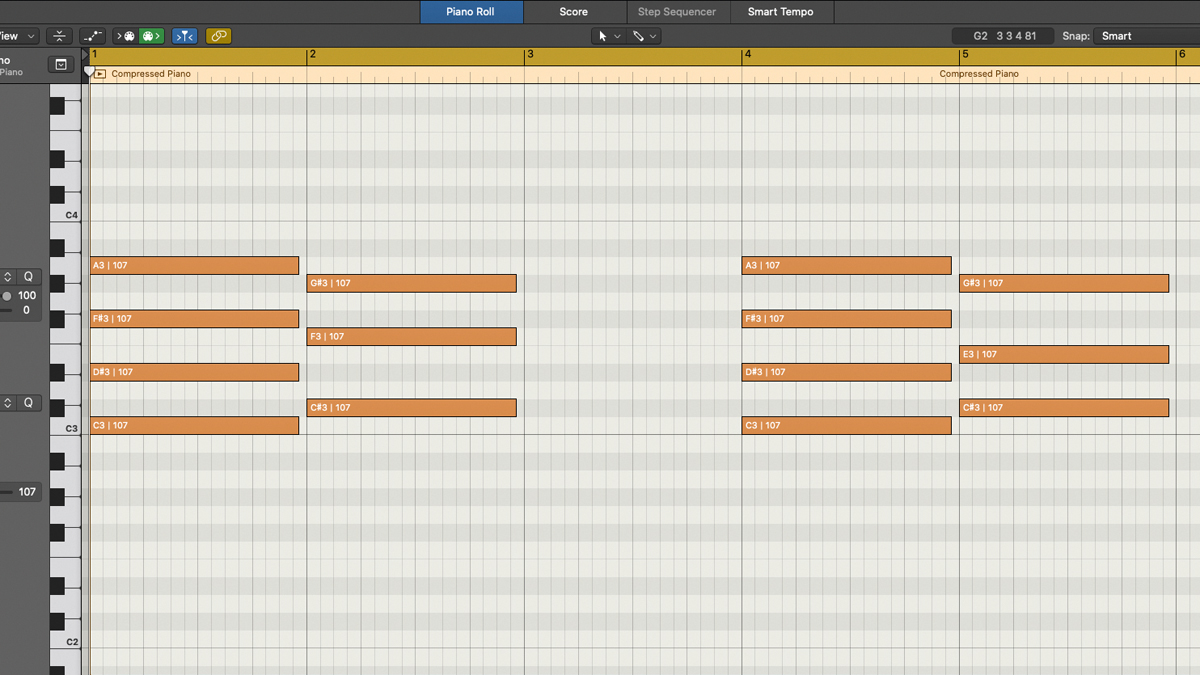

Step 1: A diminished seventh chord is a four-note chord made from notes that are spaced apart by an interval of three semitones. You can therefore make a Cdim7, for example, by playing the notes C, D#, F# and A. If we were to carry on another three semitones up from the A, we’d end up back on C again.

Step 2: This symmetrical structure means that each inversion of a dim7 chord makes a new dim7. For instance, Cdim7 (C-D#-F#-A) can be inverted and played as D#dim7 (D#-F#-A-C), F#dim7 (F#-A-C-D#) or Adim7 (A-C-D#-F#). They’re essentially just inversions of the same chord, but technically you’re getting four chords for the price of one!

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Step 3: So this means that across the keyboard, there are only three different chord shapes you need to know to play all 12 dim7 chords. Shape one: C-D#-F#-A. Shape two: C#-E-G-A# and Shape three: D-F-G#-B. This is because each of these three shapes can technically produce four dim7 chords, depending on which chord tone is used as the root.

Step 4: Dim7’s are dissonant in quality, so they’re naturally inclined to resolve to other chords. In fact, each dim7 chord can resolve to eight other chords - namely any major or minor chord rooted one semitone above any of the chord tones. For instance, Cdim7 can resolve to C#, C#m, E, Em, G, Gm, Bb and Bbm.

Step 5: Let’s look at this more closely. The notes in Cdim7 are C, D#, F# and A. Take the first note - C. One semitone up from this we have the note C#. This means that Cdim7 can resolve any major or minor chord that has C# as the root note, so that means C# or C#m.

Step 6: Now let’s look at the next chord tone in the chord of Cdim7 – D#. Similarly, one semitone up from D# is E, so this means that Cdim7 can also resolve to E or Em. And so on for F# (can resolve to G or Gm) and A (can resolve to Bb or Bbm).

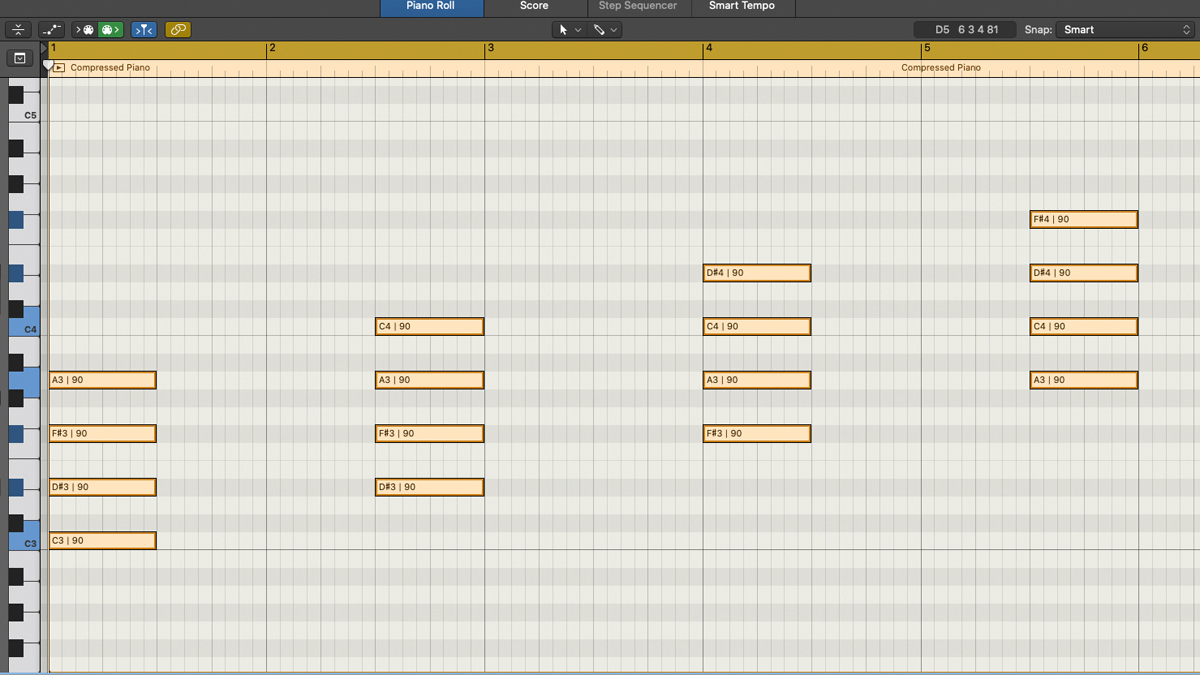

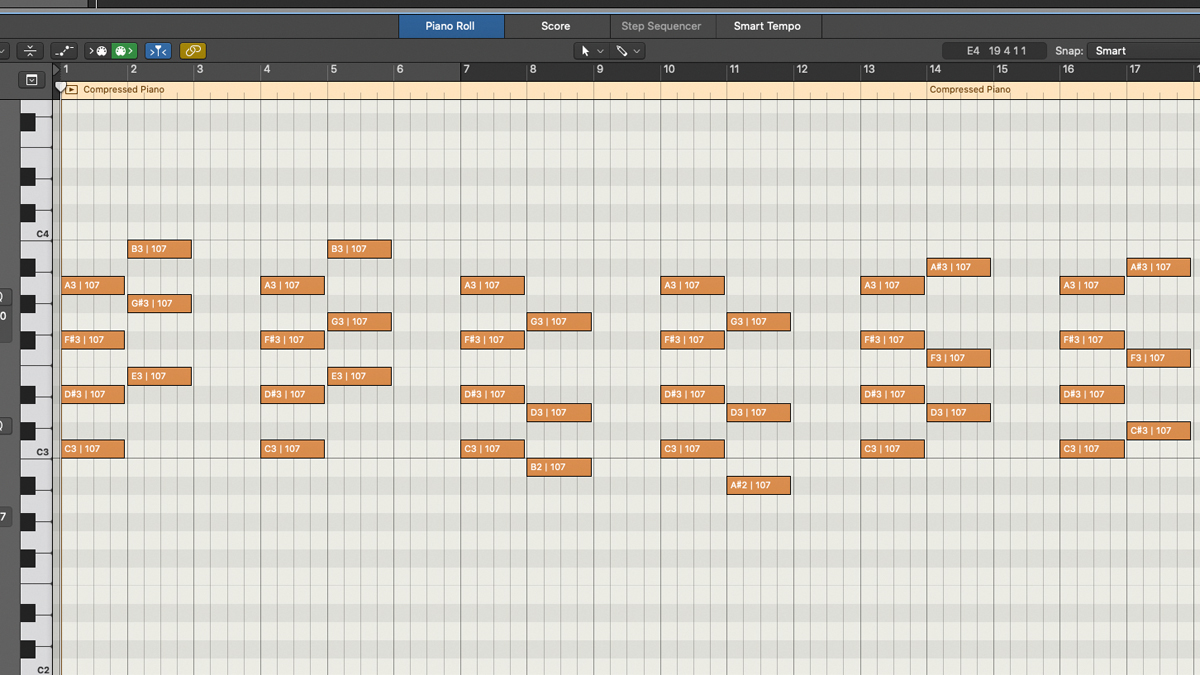

Step 7: So how can we use this unique talent in our songwriting? Let’s look at a simple, I – IV – ii – V chord progression in, say, F major. This translates to the chords F > Bb > Gm > C. Before any chord in the progression, you can insert a dim7 chord with its root a semitone below the root of the target chord.

Step 8: Let’s look at the first pair of chords F and Bb. If we place a dim7 in between, it’s going to come before the Bb major chord. The root of this chord is Bb, so we need to base our dim7 chord on the note one semitone below this, which is A. So now we have F > Adim7 > Bb at the start of our progression.

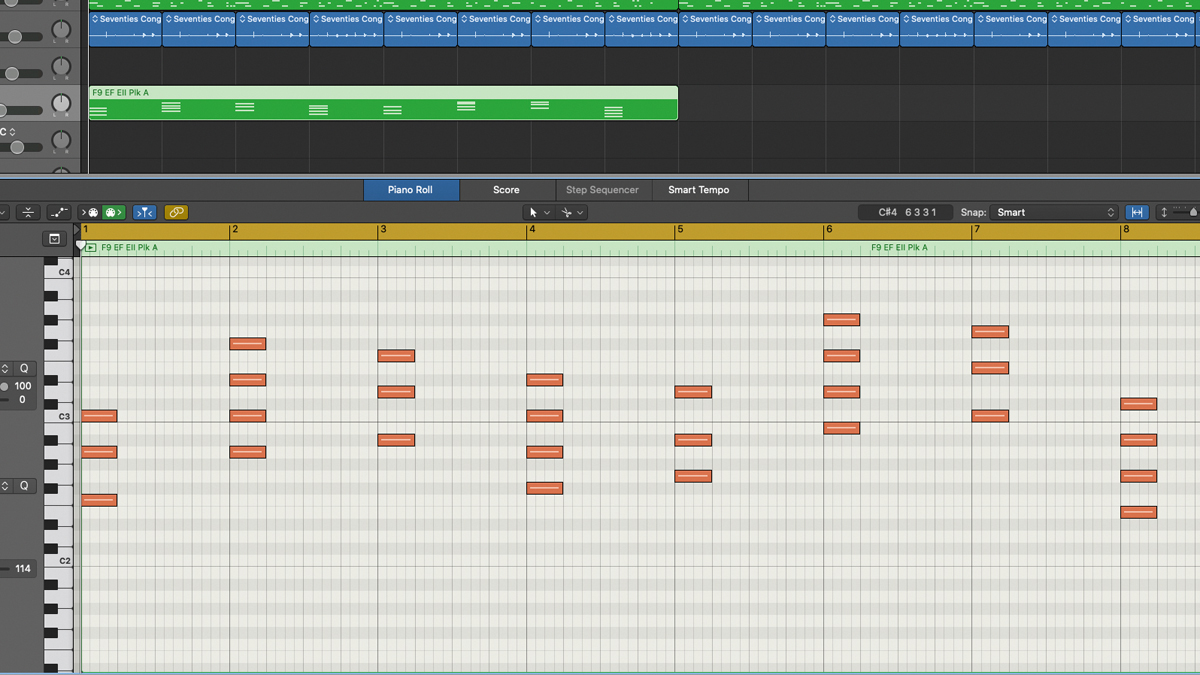

Step 9: You can do this with different harmonic rhythms. For instance, you can steal time from the preceding chord, squeezing the dim7 in as a short, passing chord at the end of the previous bar, like I’ve done here and with the next chord in the sequence: Bb > F#dim7 > Gm.

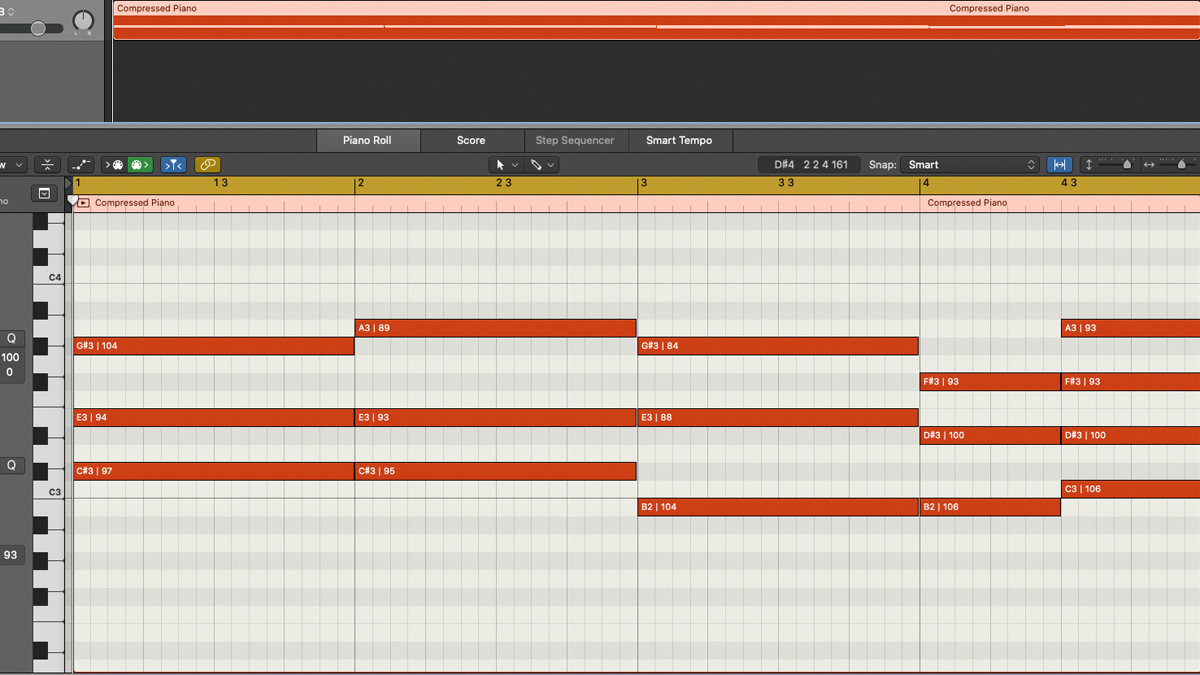

Step 10: Alternatively, you can lengthen your progression by adding a new bar for each new chord. If we do this to all the chords, we get F > Adim7 > Bb > F#dim7 > Gm > Bdim7 > C > Edim7, extending a basic four-bar sequence of simple chords into something a bit more sophisticated.

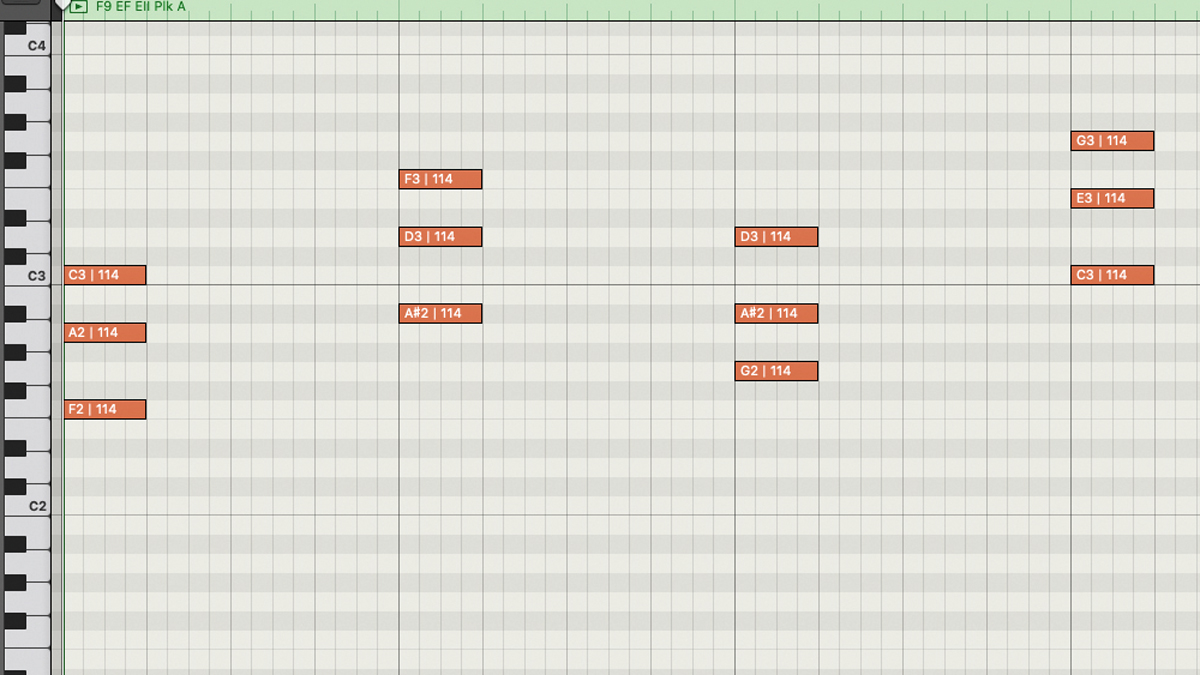

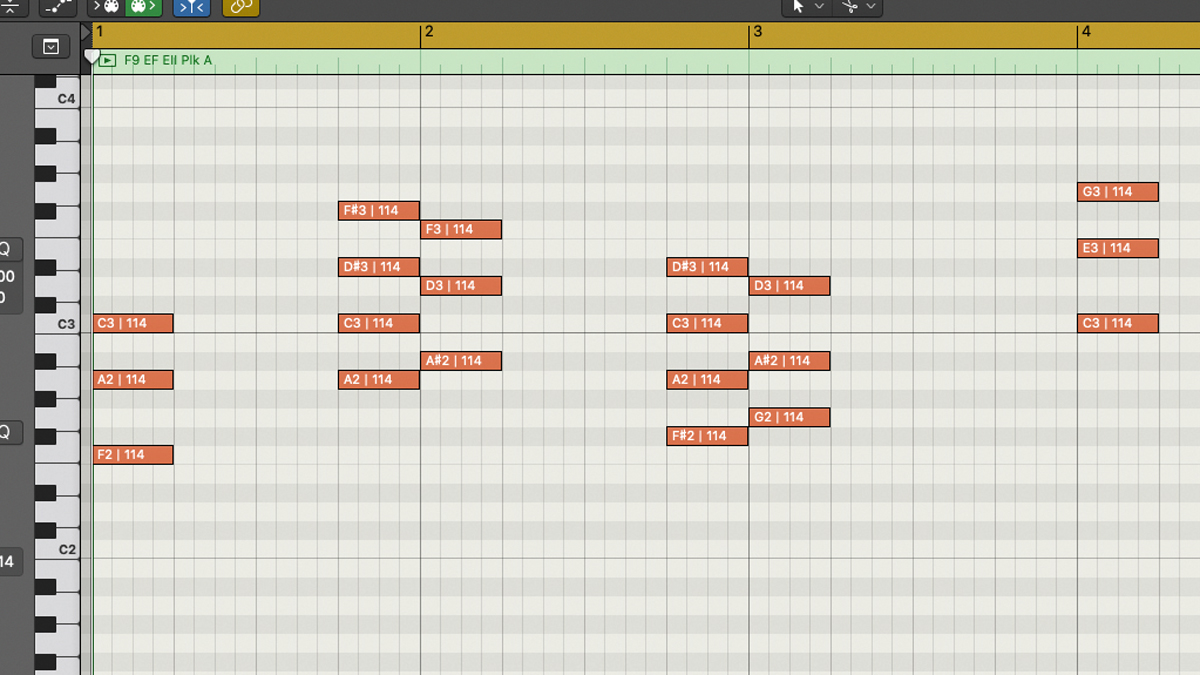

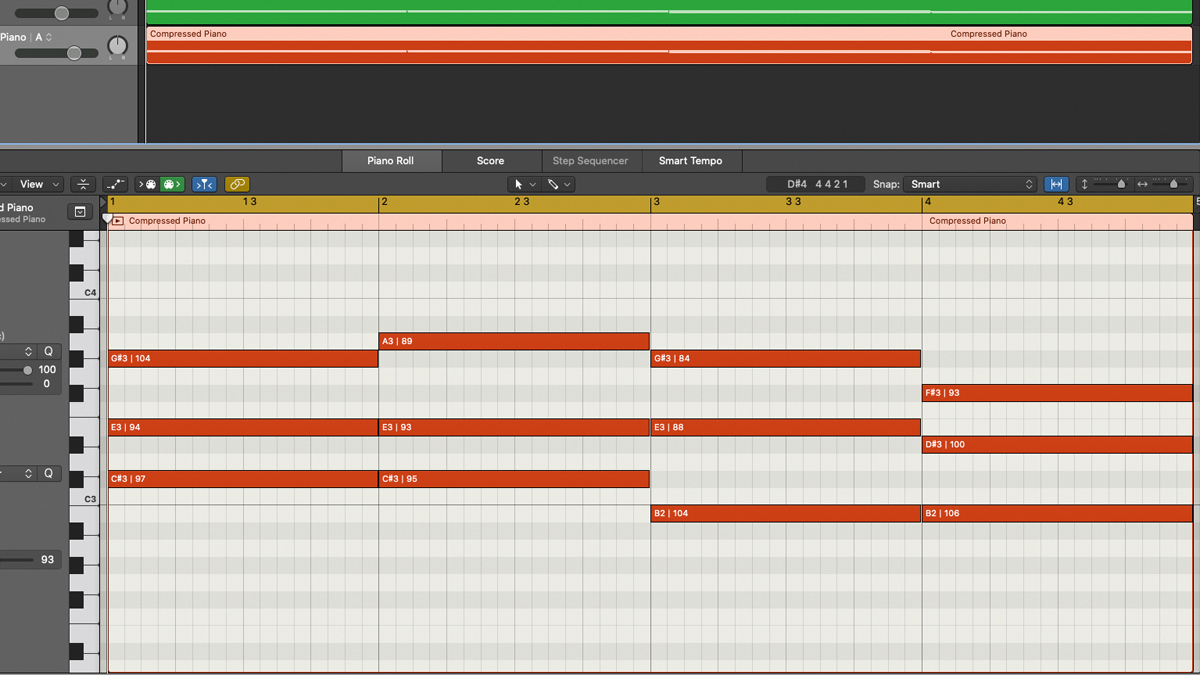

Step 11: That’s a bit extreme maybe, but even just putting one dim7 into a progression can lift it above the ordinary. Here’s a common I > VI > III > VII sequence in the key of C# minor, giving us C#m > A > E > B. Nice enough, but let’s sneak in a dim7 at the end to make it more unique.

Step 12: We’re going to add our dim7 after the final B major chord before it wraps around to the C#m I chord. One semitone below C# is C, so we need to call on our old friend Cdim7. Stealing a beat from the bar before our target chord, we shorten the B chord to make room and plug the gap with our new Cdim7 passing chord.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

Who Wants To Live Forever? The composer still creating music from beyond the grave

“How daring to have a long intro before he’s even singing. It’s like psychedelic Mozart”: With The Rose Of Laura Nyro, Elton John and Brandi Carlile are paying tribute to both a 'forgotten' songwriter and the lost art of the long song intro