Music theory basics: how to make your chords sound better by adding extra notes

Extending your chords beyond simple triads can make them sound far more interesting

In music theory, an extension is similar in concept to a house extension, except that, rather than three-bed semis, we’re dealing with three-note chords.

By definition, to extend is to make something bigger than it was before, but where builders have breeze blocks and bifold doors, we muso types have to make do with notes. The question is: which notes?

The musical equivalent of the basic two-up-two-down is the triad, a simple chordal building block made up of three notes: the root note (or tonic); a major or minor third (which determines whether it’s a major or minor triad); and a perfect fifth (or dominant).

Extensions are notes that are added above and beyond this basic triad format to make more complex chords, starting with the 7th and continuing to the 9th, 11th and 13th (or until you run out of fingers).

The notes that we use to create these extensions are found by stacking up intervals of a third, which in the case of a major scale, essentially means skipping every other note. This is why we don’t see the numbers 8, 10 or 12 in the names of these chords - when you stack up notes in thirds like this, these intervals just don’t come up.

Often associated with jazz, extensions do have their place in other genres, too. While you won’t find many 11ths or 13ths in your average pop hit, 7ths and 9ths are everywhere, so learn how to build and use them.

OK, let’s get those finger stretches on the go and lay the foundations for some extended chords…

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Step 1: To begin, here’s the C major scale, consisting of eight notes from C3 to C4. If we were to extend this scale right up to the next C, C5, we’d have a total of 15 notes to build chords from. Numbered accordingly, with C3 as the root note, you’d get C=1, D=2, E=3 etc, up to B=14.

Step 2: Let’s look at a basic C major triad, consisting of a root note (C), a major third (E) and a fifth (G). If you were to represent these notes with numbers, based on their position in the C major scale, the triad would be represented as 1–3–5. Note that the interval between each of these notes is a third - ie, we’re playing every other note of the scale.

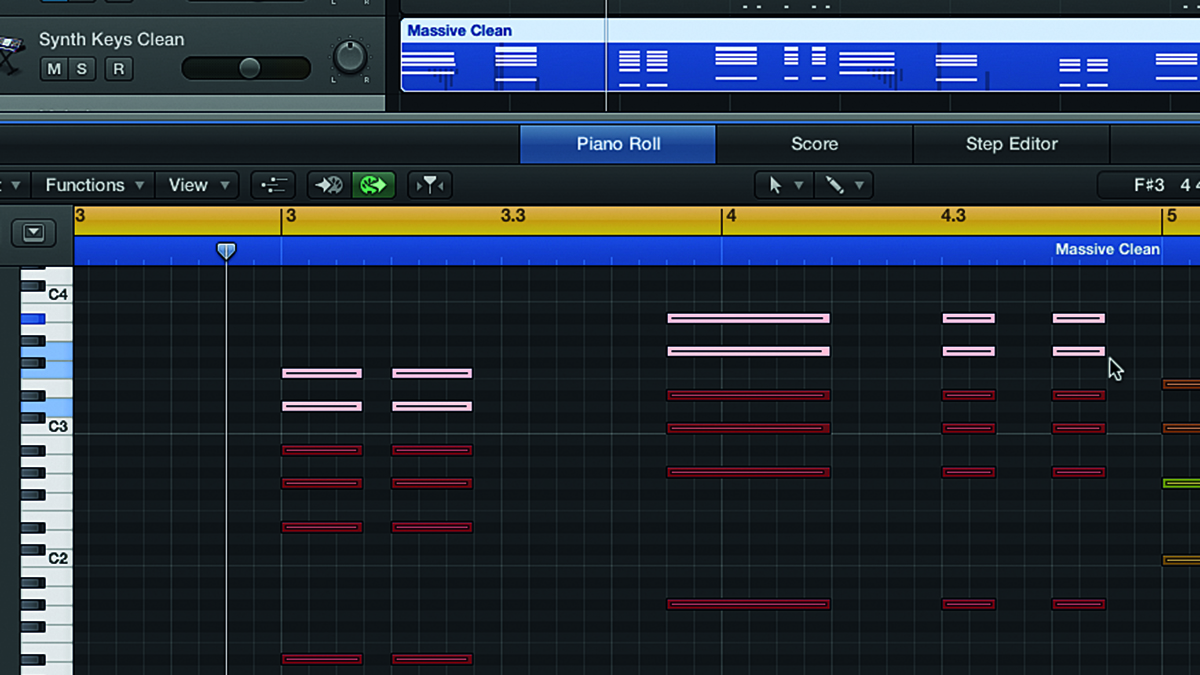

Step 3: To make the chord bigger, we need to add more notes, continuing to stack notes on top of our basic triad, keeping the same interval of a third (two notes) between each additional note. So we start to extend the chord by adding a 7th. The 7th degree of C major is B, so we add it to make a C major 7th chord - C, E, G, B (1–3–5–7).

Step 4: Taking it further, we can now extend beyond our first octave into the second octave of our scale by adding the 9th degree of the C major scale to the chord, which in this case is a D, an interval of a third above the B we just added. If we play all five notes in the chord – C, E, G, B, D (1–3–5–7–9) - we get a C major 9th chord (and a major hand cramp).

Step 5: Interestingly, if you play a C major 9th without the 7th note in it (B), it becomes known as a C add 9th chord. This is because extended chords typically include all notes up to and including their highest degree, so if you remove any in between, it changes not only the sound of the chord, but also its name.

Step 6: Since we have the rest of the second octave to explore, we can add further notes. Going up another third, we reach the 11th degree - the F note. Adding this into the mix gives us the notes C, E, G, B, D, F (1–3–5–7–9–11), which results in a C major 11th chord.

Step 7: Going up yet again, we hit the 13th degree - the A note. This gives us C, E, G, B, D, F, A, otherwise known as a C major 13th. This is the upper limit of our extended chord range, since moving up another third would take us back up to C again, at which point the numbering starts over.

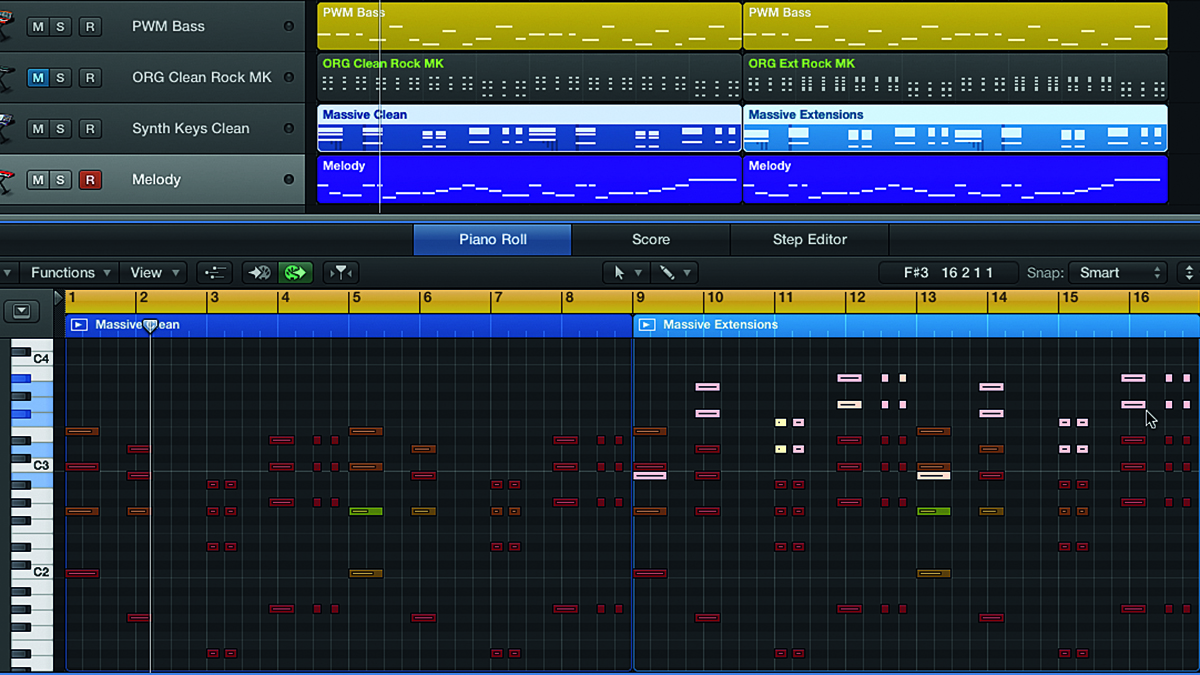

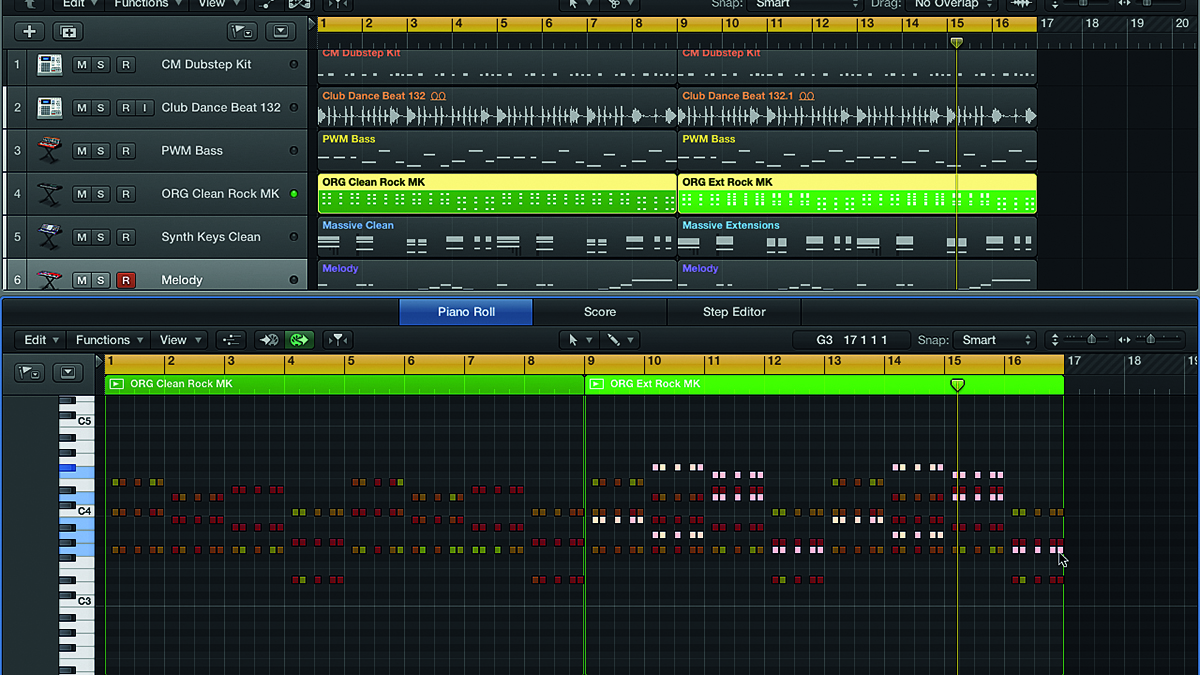

Step 8: Applying this in a musical context, let’s look at how we can make use of extended chords to liven up a track. Here we have a simple chord progression made up of major triads - C major (C, E, G), G major (G, B, D), Eb major (Eb, G, Bb) and Ab major (Ab, C, Eb). Note that C major is played here as a 2nd inversion (G, C, E).

Step 9: Starting with the first C major chord, we add a B to make it into a C major 7th - G, B, C, E (5-7-1-3). This is what we did in step 3, but, since this is an inverted triad, we now choose to place the B an octave lower. Turning to the G major triad, we add an F# and an A (the 7th and 9th degrees of the G major scale) to make a G major 9th - G, B, D, F#, A (1-3-5-7-9).

Step 10: For the other two chords, we add a D and an F to the Eb major to make Eb major 9th (Eb, G, Bb, D, F) and then add a G and a Bb to the Ab major to make Ab major 9th. (Ab, C, Eb, G, Bb). Just by using major 7th and major 9th chords, we can change the character of the progression completely.

Step 11: If we now line up two sections side by side - one containing basic triads, the other extended chords - and loop them so they play one after the other, we should be able to take a melody that works over the basic chords and play it over the extended chord progression without problems. We know the bassline will work, since the chords’ root notes haven’t changed.

Step 12: So that’s a very simple illustration of extended chords, but we’ve only covered extended major chords here. You can extend minor triads and dominant 7th chords in a similar way, but these are for another day. For now, try spicing up your progressions by swapping basic major triads for extended versions.

Pro tips

Chord in the Act

Many DAWs have a built-in incoming MIDI display that shows the notes and chords that you’re playing on your MIDI keyboard. These are usually intelligent enough to accurately display the name of whichever chord you happen to be holding down. This feature is a fantastic way to learn how to build more advanced chord shapes like maj7b5. Start off by adding extra notes to a basic chord and trying to predict how its name will change.

Major issues

With 7th, 9th, 11th or 13th chords, the use of the word ‘major’ before the number refers to the use of the natural 7th degree of the major scale. If the word ‘maj’ or ‘major’ is not present in the chord name, then the dominant 7th (one semitone below the natural 7th) is used instead. So a Cmaj7 chord would use the notes C, E, G, B (1-3-5-7 of the C major scale), but a C7 chord would use the notes C, E, G, Bb (1-3-5-b7 of the C major scale).

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.