How to use real-world sounds to guide your production decisions

Listen closely to the everyday sounds around you and you'll find parallels with various aspects of music making…

Sometimes, we find ourselves wanting to ‘design’ a sound and make something happen. “I want it to move towards me”, or, “I can’t hear that instrument over the other one”, or, “this needs to be more upfront in the mix”.

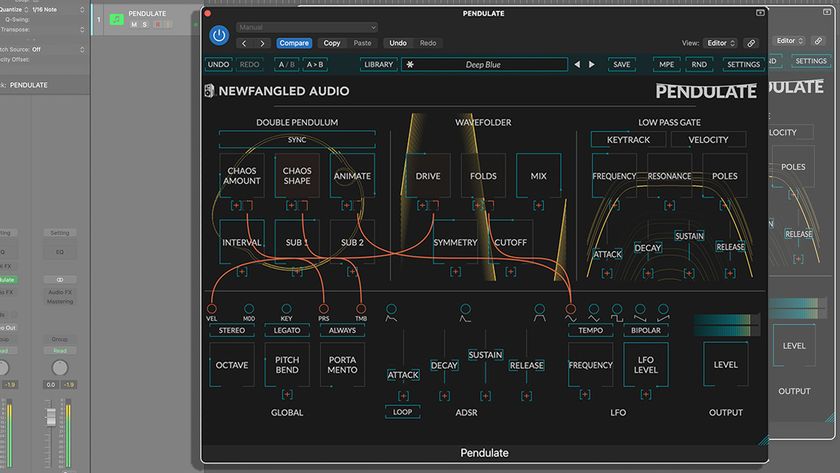

The language we use to describe what we want to hear is taken from the real world ‘sound stage’, a place that contains noise-producing objects of different sizes, in different places, each with a different impact. But the processors and tools we use to make it happen bear no relation to the real world - controls like Cutoff, Mix and Threshold don’t always translate to what we want to ‘happen’ in our virtual audio world.

In order to understand what it is we need to do to the sounds in our mix - ie, what processes we could apply, and what buttons we can press to make them behave as we imagine them - we need to start listening to the real world from a new perspective.

Consider a faraway object moving towards you - we’ll use a car as an example. When it’s far off in the distance, you hear a blurred low-frequency rumble. As it gets closer, the sound increases in level and you hear the engine more clearly. Closer still, and the higher frequencies become more apparent. Where they had been merged together, the vehicle’s direct sound and its reverb’s early reflections are more distinct and separable, and you can hear reflections from nearby surfaces all around you. As the car starts to pass you, it’s at its loudest. You begin to hear all the sounds it’s creating – the wheels scraping the tarmac, more moving parts under the bonnet, and maybe the radio through the windows.

By listening to events analytically like this, you can start to recreate them as you identify what’s going on sonically. When you’re walking about in the world, try taking those headphones off every so often. It could actually make you a better producer. Here’s how it translates…

Producing the scene

The overall loudness of the object increases as it moves towards us - we can simply emulate that by increasing the volume.

We can’t hear the highest frequencies produced by the object until it comes closer towards us, so opening up a low-pass filter over the sound (or boosting treble with a high-shelf filter) can therefore help us to mimic the car’s distance from us.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The subtle sounds that can’t be heard from afar will become apparent as the object moves towards us - these can be brought out using gain, then compression, or perhaps multiband compression. How often have you brought out the subtle parts of a snare sound by squashing the waveform a little using a compressor?

The reverb response will be drastically different for far-away and close-up objects, too. Closing the gap between early reflections and the reverb tail will give the appearance of distance, while introducing pre-delay will create a feeling of something being very close as the early reflections are separated from the dry signal.

Music production isn’t a million miles away. Consider the riser – a key part of electronic music. A filter opening up over a white noise sweep has the effect of bringing the sound closer over time. So when you’re making your next riser, take note of real-world sonic behaviours and use well-placed automation to help your FX jump out of the speakers.

Now let's put all these considerations into action to demonstrate just how powerful these techniques can be. There are plenty more production skills you can learn just by walking about in the real world, too - get to know the sounds around you, and how they change, and you’ll be able to start emulating that reality in your DAW, making sounds that engulf the listener like everyday objects.

For much more on psychoacoustic production, pick up the September edition of Computer Music.

Step 1: When we want to make something happen on our virtual sound stage, it’s good to consider how sounds work in the real world. Let’s have a look at how we can make something sound like it’s coming towards us over the course of eight bars.

Step 2: Import Car Audio.wav and make sure your project’s tempo is set to 127bpm - you’ll see why later. Our ears are used to hearing real-world sounds like this recording, so it’ll help us make accurate processing decisions.

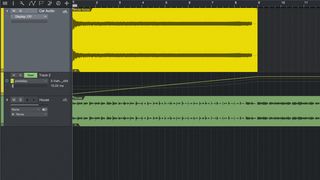

Step 3: The first, most obvious way to make something sound like it’s coming towards us is to make it louder. So, add a Gain or Utility plugin onto the sound, and automate the Gain to move from -12dB at the start to +6dB at the end. An exponential curve, as above, makes it seem like it’s coming towards us at a higher speed.

Step 4: The next cue we can give to our ears is the high frequencies. As something gets closer and closer to us, there’s less air in the way to absorb the highs, and we start to hear all the little details of the sound. We can mimic this with an EQ’s high-shelf filter.

Step 5: To make the sound come closer, automate the filter boost to rise in gain. We’ve set it up with a Cutoff of 4kHz, rising from -5dB to +13dB over the course of the eight bars. Again, we’ve created the automation as a gradual curve rather than a line, but do some critical listening to decide what feels most realistic to you.

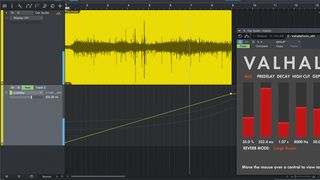

Step 6: Add a reverb plugin in series or in parallel, and dial in a large reverb signal to emphasise the effect. In the real world, as an object comes towards us, the character of the reverb might change, but more importantly, the gap in time between the initial sound hitting us and the reverb arriving will start to get bigger, making the two increasingly distinct…

Step 7: We can emphasise this with predelay. If your reverb doesn’t have one, run it on a return channel and add a delay plugin before it. Automate the Predelay to rise from about 15ms to around 400ms over the course of the eight bars, as the object comes closer and its reverb hits later. Choose your automation curve and values based on what sounds most realistic.

Step 8: Now for the proof of concept. Load the White Noise riser (White Noise.wav), which is the exact same length as the car audio, and the backing track (House.wav). Replace the car audio with the white noise audio, so that it runs through the same processing and automation. So let’s hear how our sounds work in context…

Step 9: When the processing is bypassed, it’s a very bland, basic riser that doesn’t really have any impact… but when we activate our psychoacoustic cues, it’s no longer simple pitched white noise - it starts off low and slow, gets bigger and closer, and then comes ripping through the speakers. And we worked out how to make it happen through listening to the real world!

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

"If I wasn't recording albums every month, multiple albums, and I wasn't playing on everyone's songs, I wouldn't need any of this”: Travis Barker reveals his production tricks and gear in a new studio tour

“My management and agent have always tried to cover my back on the road”: Neil Young just axed premium gig tickets following advice from The Cure’s Robert Smith