Play a guitar solo using only chords with this lesson

Blurring the lines of rhythm guitar

It's always fascinating to hear players imply the harmony of the underlying chord progression when soloing.

In fact, the backing track for this month is purely drums and bass guitar (in the old-school sense), so it leaves things open for this kind of playing. It also makes it necessary to create a sense of harmony and movement.

Listen to any trio and you’ll hear the interesting ways people meet this challenge. Jimi Hendrix developed a fascinating lead/rhythm style, and Jack Bruce played up a storm to keep things full under Eric Clapton’s solos. In this solo, the bass is only stating the root notes, so it’s all on you...

We’ve avoided falling back onto the comfort zone of the pentatonic here and tried to keep things as three-dimensional as possible in terms of harmony. We’re not talking Joe Pass or Barney Kessel, but there is a nod to the jazz-flavoured chord voicings of Robben Ford or Kirk Fletcher.

There aren’t actually that many different chord shapes being used in this piece, but they are happening in fairly quick succession, so this may not feel like a particularly spontaneous way to play at first.

However, by staying with a few basic shapes like this, it’s possible to build and expand ideas over time. Knowing your pentatonic shapes is very helpful, plus the CAGED chord shapes and the triads and inversions they incorporate.

One thing we don’t generally get to demonstrate here is the use of space and dynamics through the course of a whole piece. Sometimes, this is the perfect solution if you’re feeling flustered by all the passing chords!

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

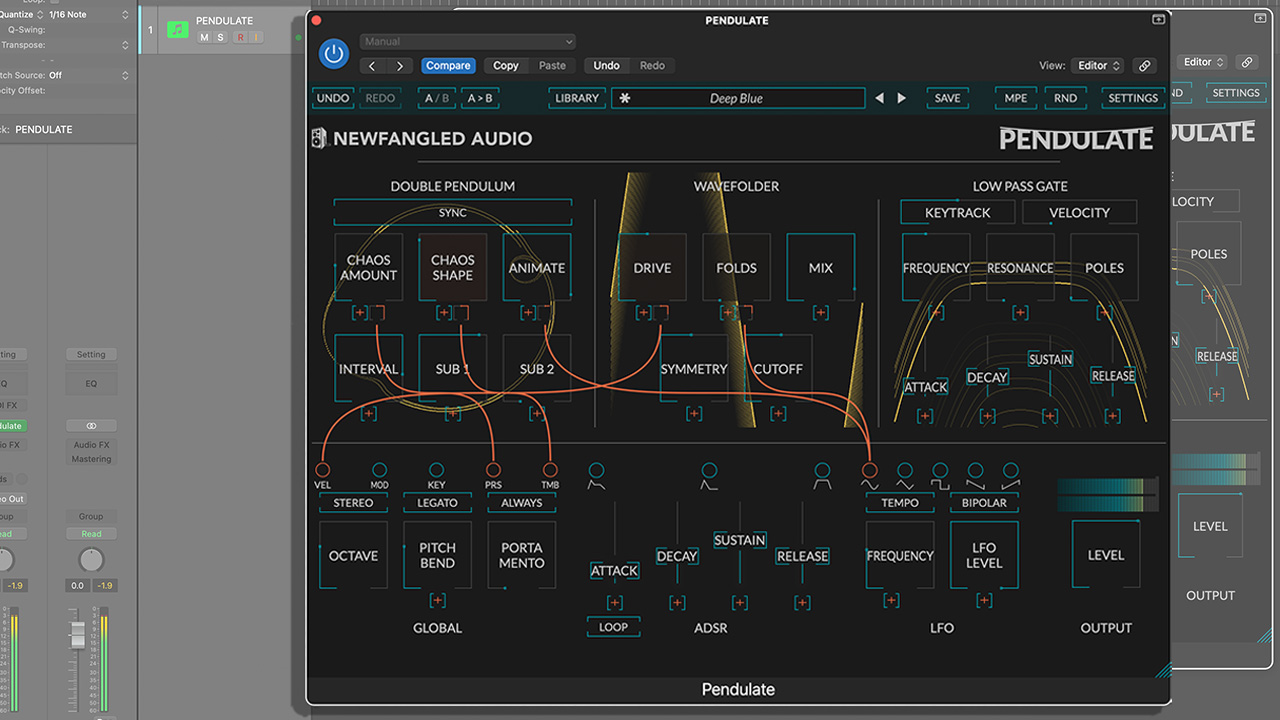

We’ve set a medium-driven sound and stuck with it, but there’s nothing to say you can’t set quite a distorted sound and roll the volume back for the chord parts, then unleash it for licks and solos.

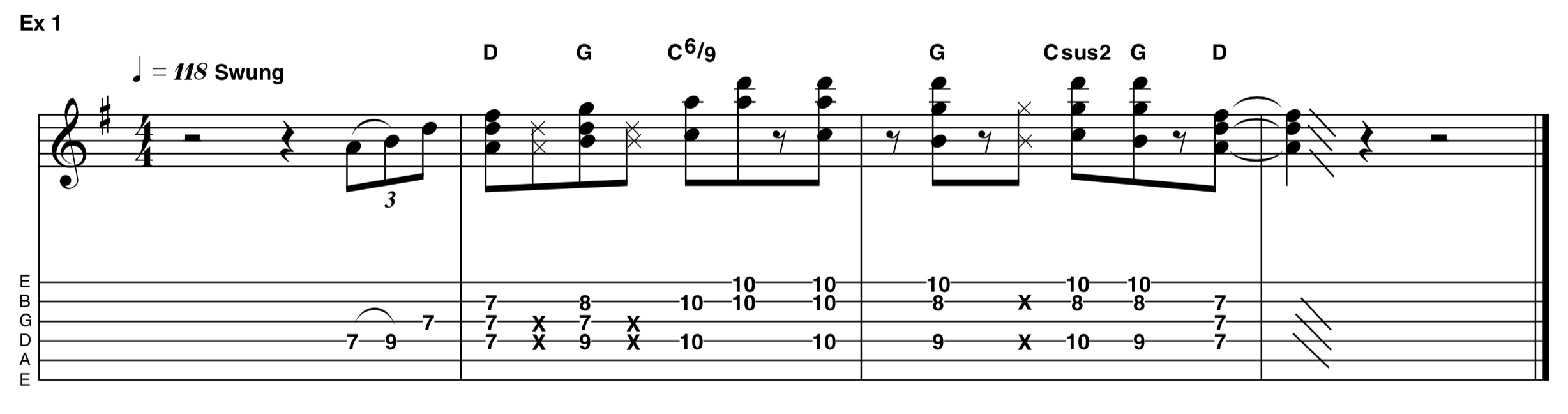

Example 1

This opening phrase is as much about the rhythm as any melodic content. Triads with widely spaced voicings like this are great for giving a ‘bigger’ sound when you’re looking to fill harmonic space. We’re using pick and fingers to enable shifting to more conventional flatpicked linking phrases, but fingerstyle is a completely valid option here, too. Why not try both and see how it influences the tone?

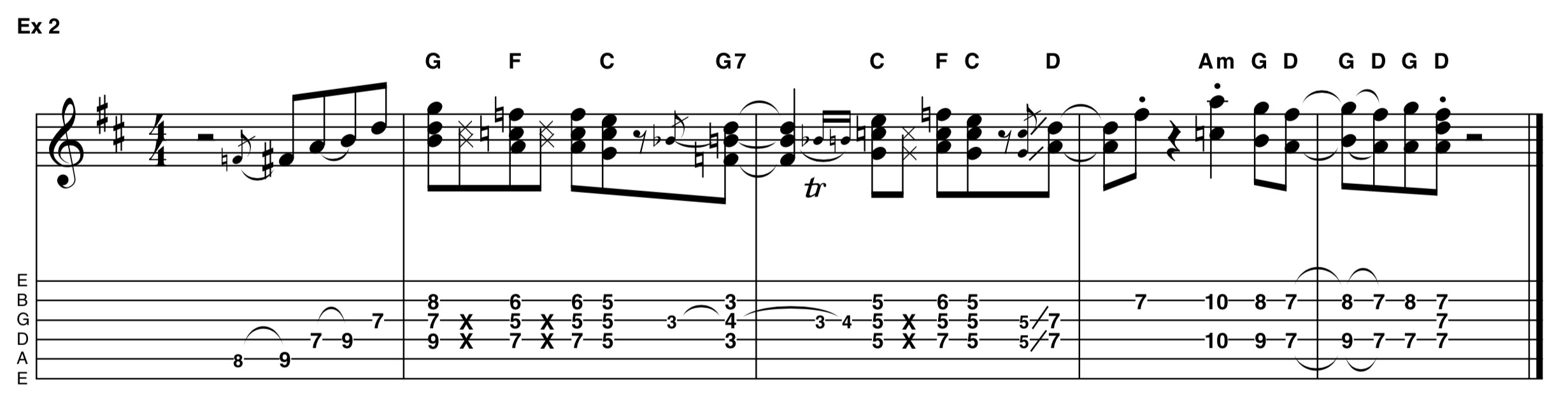

Example 2

Taking the basic harmony of a G major chord suggested by the bass, we’ve started out there, too, but superimposed the neighbouring F major, which uses the same shape, simply moved down two frets. This implies a GII chord, but came from experimentation, rather than a theory-based approach... The C major triad at the 5th fret links further to the GI triad with a trill between the major/minor 3rd (B/Bb). Like using a scale but with triads.

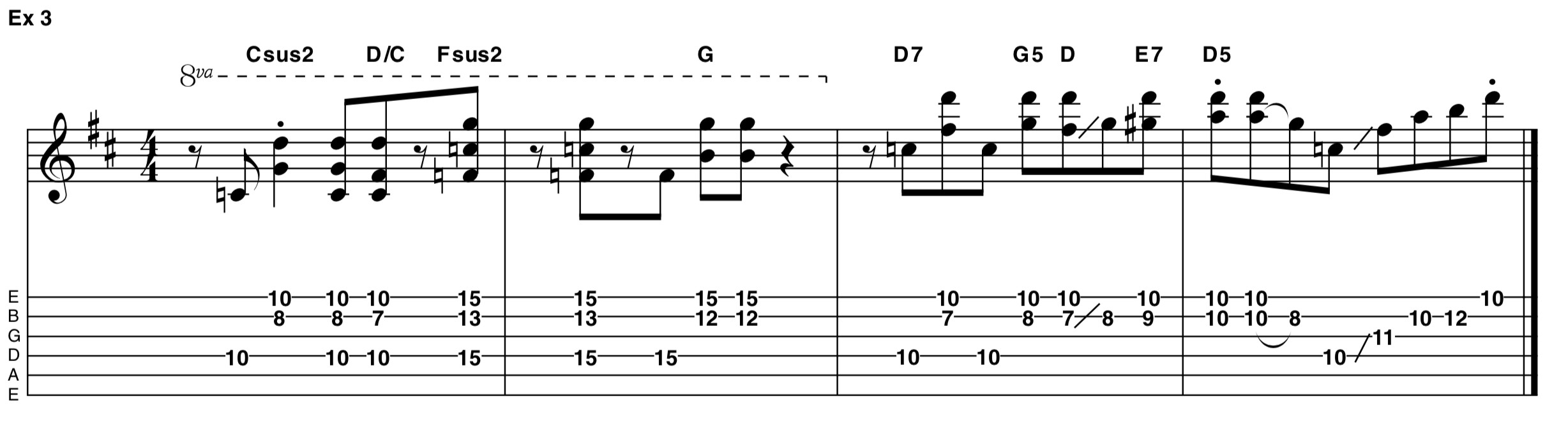

Example 3

These 7sus4 chords are a nod to Robben Ford, though you’ll hear similar on Eric Clapton’s version of Hideaway. They follow the implied chords from D to G, then back to D, where we’ve (just about!) managed to get a chromatic line in on the B string to make a doublestop lick on the top two strings. Wherever there is more than one note in play, it’s worth experimenting with moving one of the voices around.

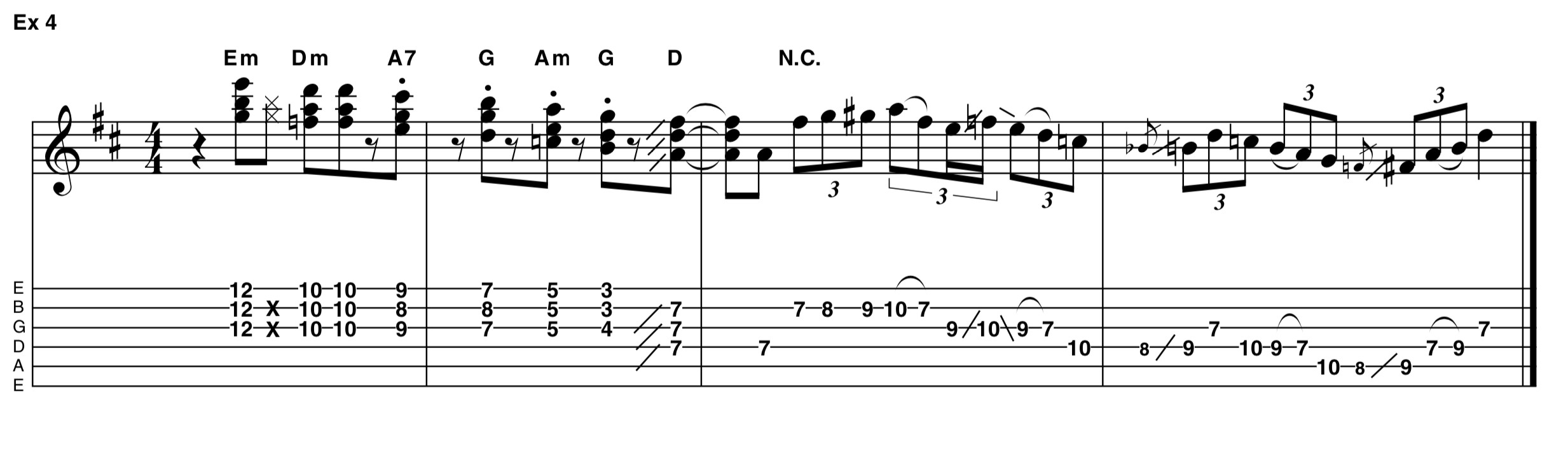

Example 4

This is another demonstration of how triads can be organised into a ‘chord scale’ pattern and superimposed over a simple backing like this. Just as you wouldn’t necessarily play only the root note of a scale, there’s no need to stick with one triad from this selection. Even if there is a little passing dissonance (intended or not), there will be melodic interest - and keeping things sharp and rhythmic gives extra time to think, too.