A quick guide to the music theory of cinematic music

Discover the compositional techniques employed by Hollywood’s biggest soundtrackers

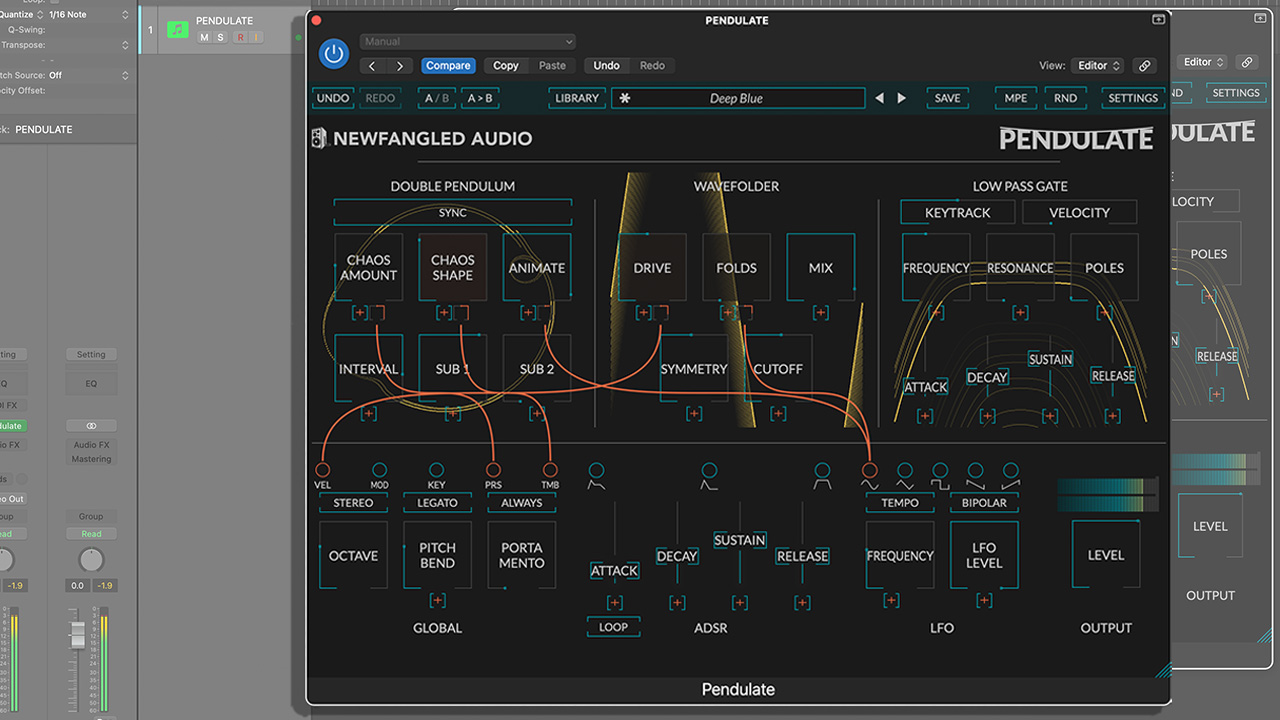

Although the tonal quality of your patches is important, it counts for nothing if you don’t play the right notes in the right order. The roots of cinematic music are found in orchestral music, and as complex as that can be, there are a few simple ideas that run through it all. Let’s break it down…

The primary goal of modern cinematic music is to be effective - reinforce the drama and lead the audience’s emotions. A Hollywood blockbuster attracts a diverse range of people, some of whom will have expert knowledge of music, some of whom will not. In order to be effective, the composer strikes the common ground between them all, trading in on common sequences and patterns found throughout music. Put simply, often the most common patterns are the most effective. Each composer leans towards certain patterns. For example, Hans Zimmer tends to write in D minor, and uses only a few different chord patterns to great effect.

A classic Zimmer-style pattern in D minor would go, Dmin - Bb - F - C. Or, for more dramatic work, a simpler pattern would be Dmin - Bb - C. It has a bold, powerful sound and can be heard all over his work in the Batman films and Inception. Other composers, such as John Carpenter and Cliff Martinez, tend to use ‘pedal tones’ and arpeggios to lock the audience in.

Feeling designer

Whatever the pattern, an essential skill is the ability to set an atmosphere or mood. There are, of course, broad generalisations - such as using major keys for happy scenes and minor keys for sad - but cinematic music requires a much more complex look at mood and emotion. The onscreen action may call for a sense of ‘wonder’ - how do we reach out to the audience to make them feel that through our sound design and note choice?

First and foremost, the sound we use should reflect the mood. Try using softer tones for gentle moods, and bolder sounds for the more dramatic. It’s no accident that the orchestra brings out the big brass section when the bad guy appears on screen, so reflect this in your sound design.

Soundtrack secrets

There’s one particular scale that might be considered the film composers secret weapon: the Lydian mode. It’s used all over film music and is regularly employed by giants such as John Williams and Thomas Newman.

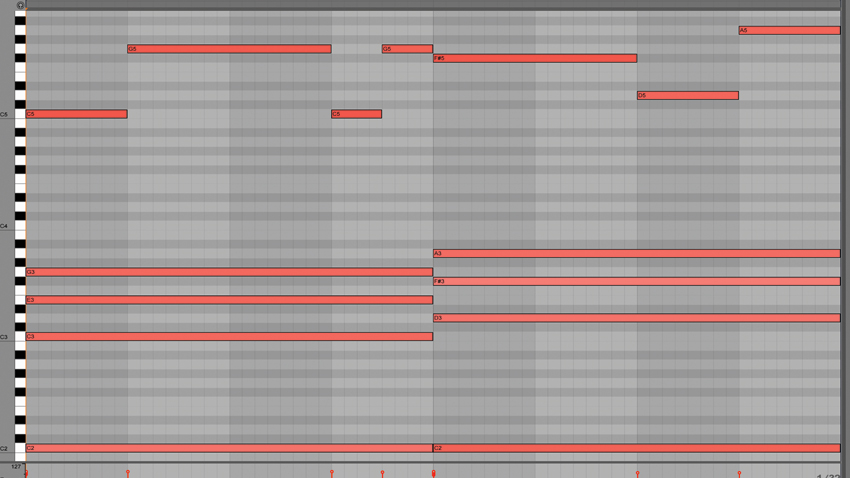

The Lydian mode takes the fourth note of the major scale and moves it up by one semitone. So in the key of C major, the note F is replaced with an F#. This simple change can produce some wonderful cinematic melodies. A similar voicing can be heard in a very common cinematic chord pattern. Try playing C major then a D major over a constant C bass note (shown in the screenshot below). This ‘rising’ pattern is often heard at the climatic point of a movie - the end of ET, for example.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Adding some surprise value is one key to memorable music. A common trick is to play around a popular chord sequence so that the audience is comfortable, recognising the pattern and predicting what will come next. Once you have them relaxed, change things up a bit by inserting a chord to take them by surprise. John Williams is a master of this technique, The Raiders March from Raiders of the Lost Ark being a superb example. Be careful what you surprise them with, though - stray too far from the predictable and you’ll lose your audience quickly!

Three cinematic synth soundtracks

Hans Zimmer, Atmospheric Entry

Although Mr Zimmer is usually known for his pounding drums and momentous horns, he also utilises synthesised textures in his scores to create tension and atmosphere. This piece from the movie Interstellar is a great example of a minimal soundscape, creating a tense backdrop to the onscreen action. Simple, but most importantly, effective.

Cliff Martinez, Rubber Head

Cliff Martinez provided a lot of the synth-heavy music for the movie Drive. In this track, he sets the tone with an ominous atmosphere, then locks the audience in with a hypnotic arpeggio. This is a great example of setting the mood with an atmospheric pad, then giving the audience something a little more melodic to concentrate on.

Vangelis, Blade Runner

What discussion about synths in cinema could be complete without mentioning the score to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner? Vangelis’ lush pads and now-classic synth lead create a brooding atmosphere, transporting the viewer into the dystopian future. It paved the way for many synth scores and still sounds brilliant nearly 35 years later.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

Who Wants To Live Forever? The composer still creating music from beyond the grave

“How daring to have a long intro before he’s even singing. It’s like psychedelic Mozart”: With The Rose Of Laura Nyro, Elton John and Brandi Carlile are paying tribute to both a 'forgotten' songwriter and the lost art of the long song intro