9 genre-spanning music theory hacks: make better R&B, pop, trance and techno

Make better R&B, pop, reggae, blues, funk, jazz, trance and techno

You might think of music theory as a dry and academic subject, but its 'rules' tend to be followed in even the most cutting-edge genres.

If you don't believe us, check out the following nine tips, which demonstrate how theory can be applied to your productions no matter what kind of music you're making.

1. R&B: subsidiary chords

Subsidiary chords share two or more chord tones, and thus can be switched out for each other because they share the same harmonic function.

Say you have a I-I-IV-V progression in C major (C-C-F-G). To find the subsidiary chord of a major triad, we simply raise the fifth by a whole tone. So the subsidiary of C major (C-E-G) is A minor (C-E-A). This can now be substituted for the second C major chord in our progression, giving us I-vi-IV-V (C-Am-F-G).

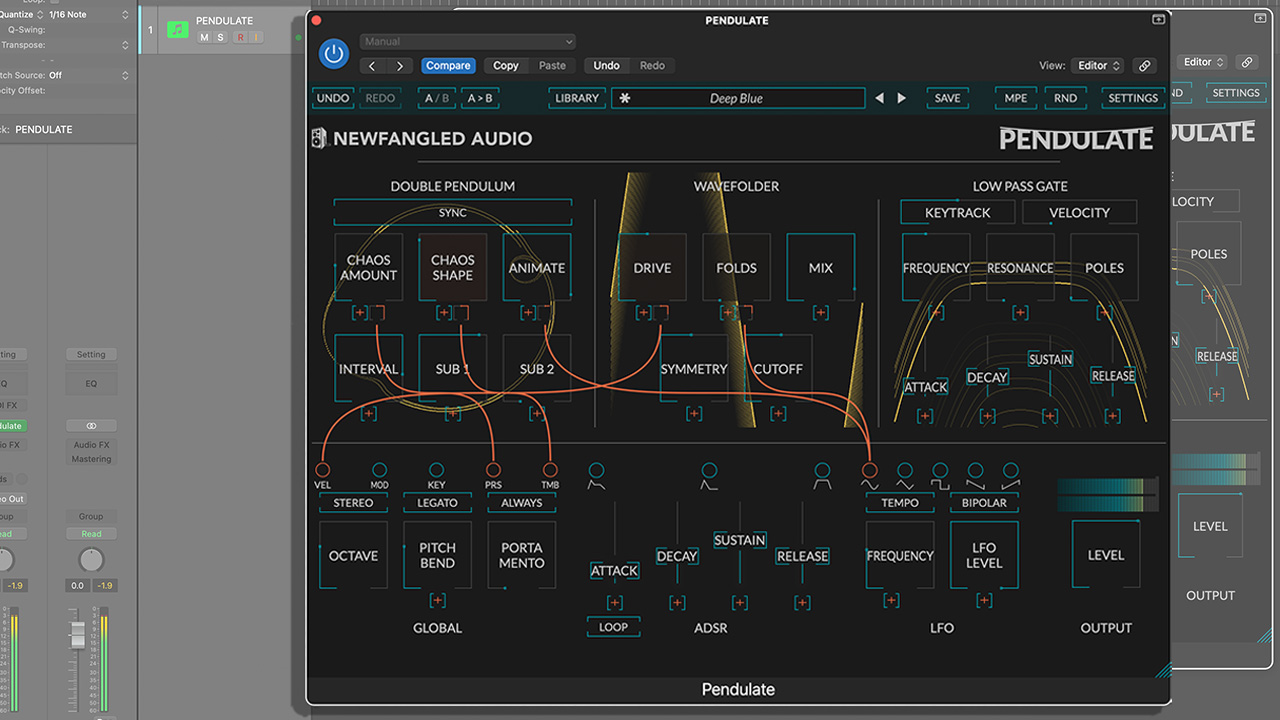

2. Trance and techno: 16th-note sequences

Like most dance music, trance and techno are most comfortable in a 4/4 rhythm, which is usually pinned down by a solid kick drum on all four beats in the bar. This provides the perfect backdrop for 16th-note bass and synth sequences to drive the rhythm along. Rather than just filling the whole bar with a note or chord on every beat, however, create different rhythmic effects by removing notes here and there, then shifting or lengthening the remaining notes to create space around the kick drum beats.

3. Pop: modulation with pivot chords

In a music theory context, modulation means moving to a different key, and it can be achieved in several ways.

One method is to use a chord common to both keys as a ‘pivot’ chord. This enables you to have a verse in a minor key (Am, for example) and switch to the relative major key (C) for the chorus.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Luckily, relative keys share all the same diatonic chords, making this kind of modulation fairly straightforward. So, a pre-chorus in the key of Am that ends with a G major chord (the VII chord of Am and the V chord of the key of C) will resolve to a C major chord, allowing you to kick off the chorus with the tonic of the new key of C major.

4. Reggae: the ‘skank’

Reggae has a very distinctive sound that’s defined by a few signature elements, including the ‘one-drop’ kick drum plus sidestick rhythm pattern, deep bass guitar tones and tape echo dub delays.

Probably the most recognisable reggae trademark though, is the off-beat ‘skank’ - a rhythm part made up of a chord, usually a major or minor triad, played on every even-numbered eighth-note. Extended chords such as major and minor sevenths are also often used, but suspended or diminished chords crop up less often.

In terms of instrumentation, the skank is normally handled by the guitar, piano or organ. When an organ is used, there’s also the option to go for a two-handed shuffle. This involves playing staccato chords in a choppy eighth-note pattern but leaving the downbeats empty - ie, Rest-Left-Right-Left-Rest-Left-Right-Left. With the right organ sound (usually a Hammond B3-style tone), the result is a very percussive groove that complements the rhythm section’s overall emphasis on the third beat of the bar.

5. Blues: soloing tips

When soloing over minor progressions, using either the minor pentatonic (1, b3, 4, 5, b7) or minor blues (1, b3, 4, #4, 5, b7) scales. All five notes in the minor pentatonic fit over any chord in the standard blues progression, so you can stick to one scale and it should work.

The major pentatonic scale (1, 2, 3, 5, 6) can be used to solo over progressions containing major triads, 7th and major 7th chords, because it lacks a 7th degree. However, the major pentatonic scale only works with one chord at a time, meaning that you should use the A major pentatonic scale when soloing over A7, for example, but when you switch to D7, you should use the D major pentatonic.

6. Funk: minor 11th polychord

Minor eleventh (m11) chords are great for spicing up jazz or funk progressions, and they can be formed in two ways: by spelling out the six-note formula 1-b3-5-b7-9-11 (which for a Cm11 is C-Eb-G-Bb-D-F), or by playing two triads together to make a polychord.

For an m11, play a minor triad with the desired root with your left hand (Cm in this case), then work out the note a whole tone below the root (Bb) and use your right hand to play a major triad based on it (Bb). The result? Cm11!

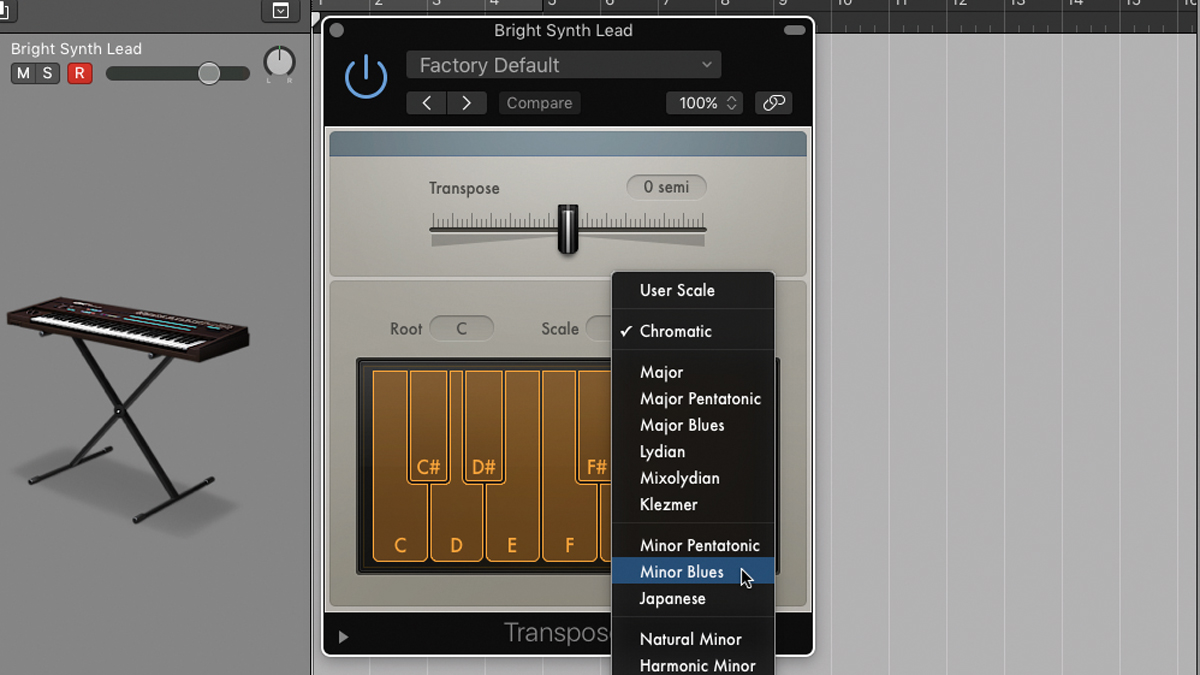

7. MIDI transformation for any genre

Use a MIDI transformer app (such as AutoTonic or AutoTheory), a dedicated MIDI plugin or scale lock mode in your DAW to fix MIDI input data to the key of your song. Used properly, these devices make it impossible to play a note out of your selected key and scale, so you can plonk around randomly on the keys and still end up with something useable.

You do have to work out the key your song is in, mind, and which scale you want to use; but even if you know a lot about theory, you can get some unexpectedly cool results using this technique.

8. Jazz: tritone substitutions

Substitution means replacing one chord with another one that performs the same harmonic function, and tritone substitution is a popular example of this in jazz.

A tritone is an interval of three whole tones (six semitones), so in a tritone substitution, a chord is replaced by one whose root note is a tritone away from the root of the original chord.

In our example, we’ve got a ii-V-I progression in the key of C major: Dm, G, C. We can replace the V (G) with Db - three whole tones down from G - for a jazzier, ii-bII-I sound that still resolves nicely back to the C.

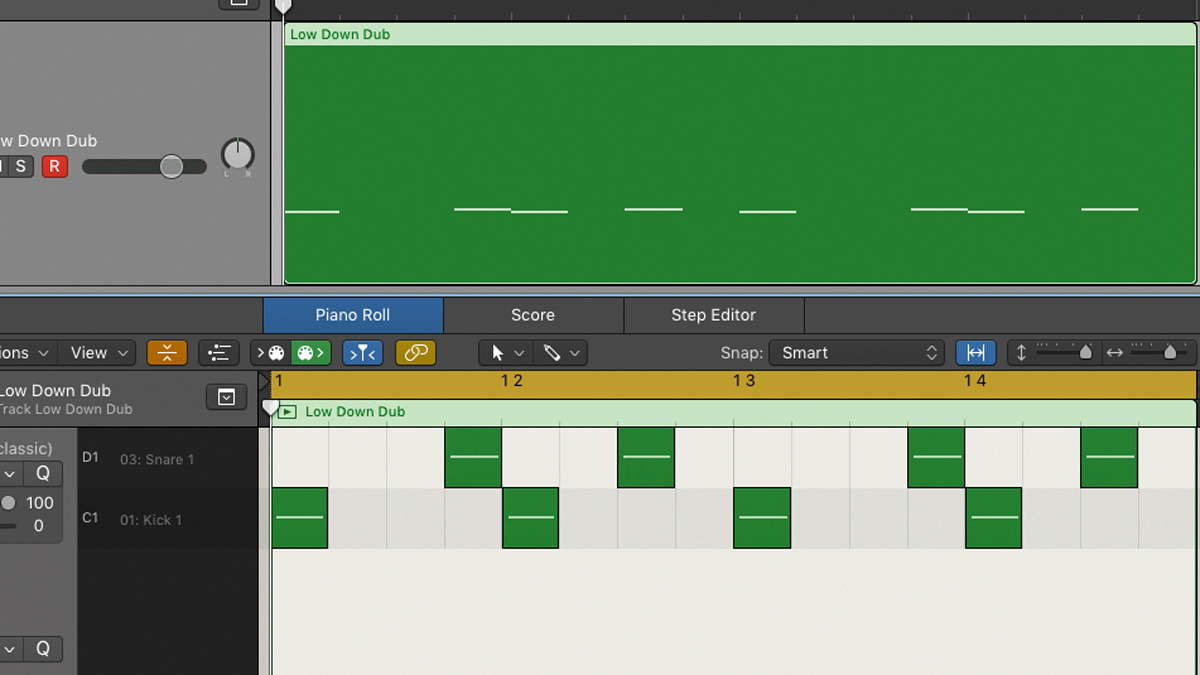

9. Dancehall-pop: dem bow

Unlike traditional Caribbean dancehall songs, dancehall-pop music fuses authentic dancehall rhythms with material found in mainstream pop music, such as repeated choruses, melodic tunes and vocals with lashings of hard pitch correction.

The rhythm this genre uses is known as ‘dem bow riddim’ - it features a 4/4 kick drum at a medium tempo, with the 16th-notes of each bar divided into accents on 3+3+2+3+3+2, usually played on the snare to give a pushed, rolling feel to the track.

MusicRadar is the number one website for music-makers of all kinds, be they guitarists, drummers, keyboard players, DJs or producers...

- GEAR: We help musicians find the best gear with top-ranking gear round-ups and high-quality, authoritative reviews by a wide team of highly experienced experts.

- TIPS: We also provide tuition, from bite-sized tips to advanced work-outs and guidance from recognised musicians and stars.

- STARS: We talk to musicians and stars about their creative processes, and the nuts and bolts of their gear and technique. We give fans an insight into the craft of music-making that no other music website can.

“How daring to have a long intro before he’s even singing. It’s like psychedelic Mozart”: With The Rose Of Laura Nyro, Elton John and Brandi Carlile are paying tribute to both a 'forgotten' songwriter and the lost art of the long song intro

“The verse tricks you into thinking that it’s in a certain key and has this ‘simplistic’ musical language, but then it flips”: Charli XCX’s Brat collaborator Jon Shave on how they created Sympathy Is A Knife