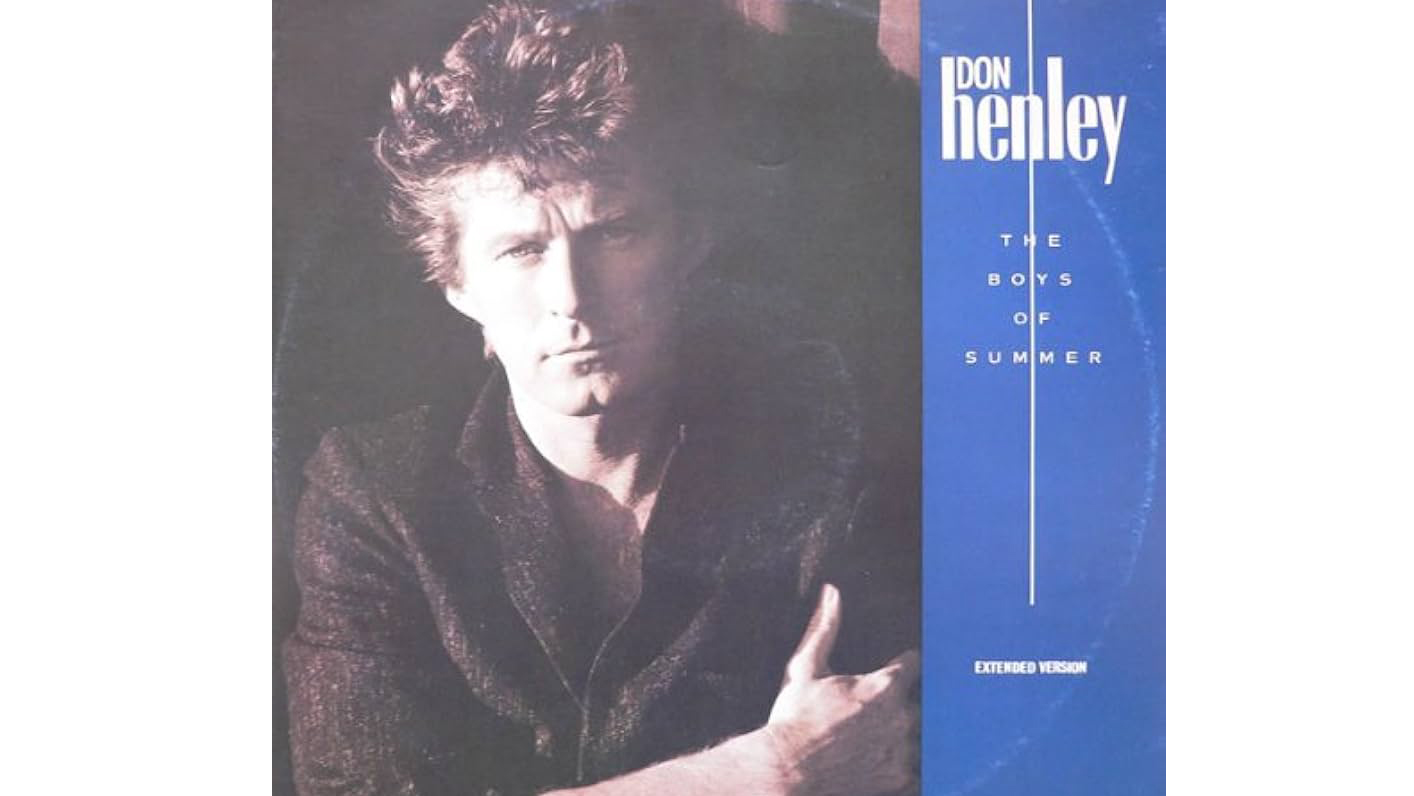

"He didn't tap a foot or move his head or anything. He listened to it all the way through and I thought he hated it": When an Eagle, Heartbreaker, Roger Linn and an Oberheim OB-X combined forces for a pop masterpiece – the Boys Of Summer story

Join us for our traditional look back at the news and features that floated your boat this year.

Best of 2024: "This song almost didn't happen," reflected Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers guitarist, songwriter and all-round rock hero Mike Campbell two years ago. It's incredible just how many famous songs nearly didn't take flight, or were recorded by artists they were never intended for. Pharrell Williams' Happy was rejected by CeeLo Green's label, Britney Spears' management turned down Umbrella. Simple Minds even turned down Keith Forsey's Don't You (Forget About Me) six times.

Jim Kerr and Co wisely relented on that one, but some songs just need their time, place and the right artist to achieve any of the potential they might hold. Or luck. Some are just not suitable for their intended muse at the time. Which is what happened with Campbell's demo that would become the 1984 Don Henley hit Boys Of Summer. Well, it's some of what happened with it – the rest was less straightforward.

I had a friend named Roger Linn

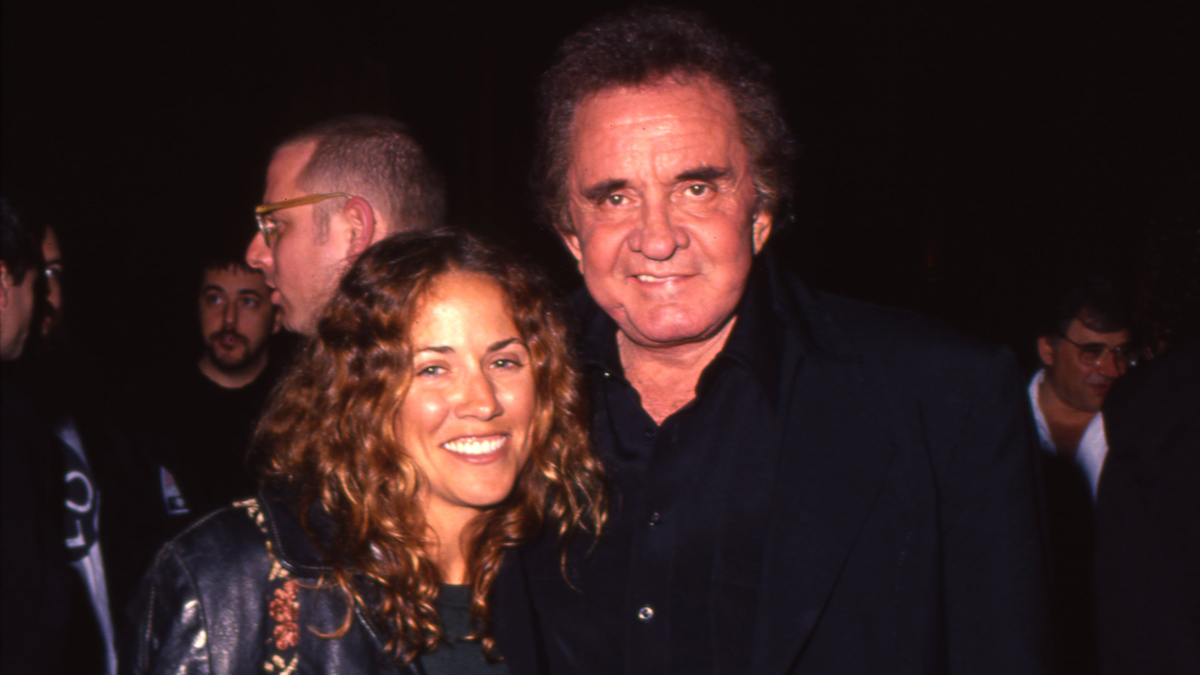

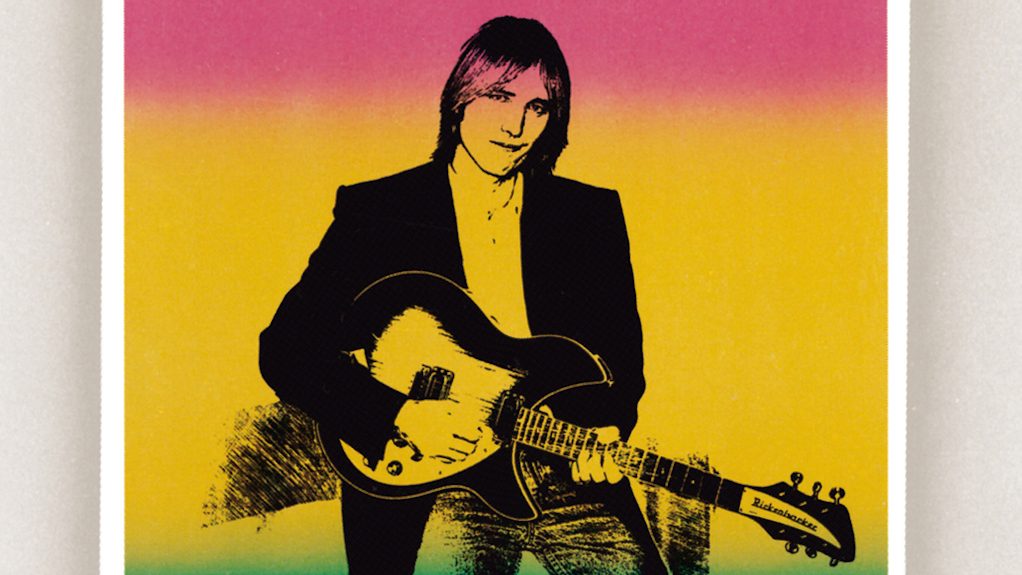

Mike Campbell

"Back in the day, thanks to my wife, I had a Teac four-track tape machine," Campbell explained in the video (via YouTuber Ken Power) you'll find down below, filmed a couple of years ago. "And I had a friend named Roger Linn who used to work over at Leon Russell's house. Tom [Petty] and I would go over there and Roger would always be in the back room and we said, 'What's he doing back there?' They said, 'He's building a drum machine.'

Neither Campbell nor Petty had heard of such a concept before – and no wonder. Linn was breaking fresh ground that would open up into a world of creative possibilities in the near future. This was early days for the LinnDrum but it would find its way onto hits around the world in the '80s, including A-ha's Take On Me. Campbell was certainly intrigued and inspired.

"The first one he built was called LinnDrum," continues Campbell [it was actually the second after the LM-1 released in 1980]. "It had a bunch of live sounds that you could mix together like a drum machine and make your own patterns – it was pretty revolutionary at the time."

I stayed up all night, just typing in tambourines and claps and hands and drums and snares. I got a little pattern going

Mike Campbell

Campbell was convinced enough to buy one at "FOR" - Friend Of Roger price. He installed it into a streamlined home studio in his spare bedroom, alongside the aforementioned four-track. But Campbell wasn't done with branching out into new electronic territory.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I had borrowed an Oberheim OB-X synthesiser and I was playing around with the drum machine one night," Campbell remembers. "I stayed up all night, just typing in tambourines and claps and hands and drums and snares. I got a little pattern going."

An infectious ear-worm synth hook followed, followed by some overdubbed guitars. Campbell had something but "didn't think much about it".

"A week later Tom Petty and [producer] Jimmy Iovine were over at my house and I played them my demo and they said, 'I think that's a little jazzy for what we're doing right now' and I agreed with them. I put it aside and this song almost didn't happen – it could have ended up on the shelf still collecting dust."

Campbell later admitted he was pretty dejected by the response, but the idea just wasn't deemed suitable for the album they were working towards at the time, 1985's Southern Accents. It also had a different chord change for the chorus that had been the part Iovine had deemed "jazzy".

The decision was something Petty would later regret as we'll find out. But Iovine saw enough potential to later recommend Campbell take it to another high-profile artist.

"He called me a week later and told me Don Henley was looking for some music for his first solo record, and I remembered that track and he did too," remembered Campbell.

He went back to work on the idea, before tracking it to cassette and passing it on to Henley in person – a musician he'd never met before.

As Henley's former Eagles bandmate ('mate' is probably an optimistic word here) Don Felder once noted to MusicRadar, "The one thing about Don Henley is, he's a great singer, great lyricist and a great songwriter, but he doesn't play anything. He plays drums. He can't pick up a guitar and write chord progressions; he can't sit at a piano and write music underneath him."

Maybe so, but like Hotel California proved before, he was exactly the musician that a demo idea needed to become a timeless song that's still a drivetime classic. Except Campbell initially thought the notoriously tough cookie Henley was going to reject his idea outright.

It was Don, he said, 'I've written the best song I've written in ten years

"He sat at the end of a long table and he had a cassette player, he put a cassette on and he just did this [motions with arms folded and head down]," Campbell recalled. "He didn't tap a foot or move his head or anything. He listened to it all the way through and I thought he hated it."

Even when the song finished the reaction from Henley was somewhat muted, though the Eagle told Campbell he'd work on it. But the creative wheels were soon turning fast; Campbell got a phone call.

"It was Don, he said, 'I've written the best song I've written in ten years' and I said, 'Ok let's go and make the record.'"

Henley's inspiration had come fast; he seemed to be wistfully looking back on lost love with his lyrics, but the former English and philosophy student at North Texas University was also able to inject some deeper symbolism about biting contemporary observation.

The title itself alludes to the Dylan Thomas poem I See The Boys Of Summer but it's indirect – it's actually from Roger Kahn's 1972 book about the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team which was inspired by the late Welsh poet's title. Henley is a baseball fan but the inspiration stopped there. "It's not about baseball really, it's about life – looking back," Henley told Howard Stern in 2015. "I have a thing about looking back."

The status symbol of the right-wing upper-middle-class American bourgeoisie – all the guys with the blue blazers with the crests and the grey pants – and there was this Grateful Dead 'Deadhead bumper sticker on it!

Don Henley

Elsewhere, Henley was more specific when drawn on a line from one of the verses in particular.

"I was driving down the San Diego Freeway and got passed by a $21,000 Cadillac Seville," Henley told the NME in 1985 regarding the 'Deadhead sticker in a Cadillac line' in Boys Of Summer. "The status symbol of the right-wing upper-middle-class American bourgeoisie – all the guys with the blue blazers with the crests and the grey pants – and there was this Grateful Dead 'Deadhead bumper sticker on it!"

But the lyrics weren't a problem – there would be unforeseen challenges that emerged for Campbell in the studio. Starting with the LinnDrum.

"This is where this song almost didn't happen," recalls Campbell in the video about the song below. "The LinnDrum, back then you would save your patterns onto a cassette. So you'd stick the cassette in and you'd call up the pattern you had, which was Boys Of Summer, you'd push 'save' and it saves some kind of digital thing onto the cassette. Then when you want to put song back in, you put the cassette back in, press load and voila your song comes in.

"So I went down to the studio with my little LinnDrum, sat out in the room. They said, 'Ok go put on your drum machine and we'll record it onto the analogue tape.' And I sat on the floor out there and I pushed play and it just said 'error'.

My song's gone, I'm gonna look like a fool, they're thinking I'm an idiot – the thing didn't work

Mike Campbell

Cue mild panic as Campbell tried loading his cassette again five or six times. "Every time I would push 'load' it would say 'error'", he remembered. The studio staff were now waiting and the situation was edging towards desperate as Campbell's music depended on the LinnDrum part: "My song's gone, I'm gonna look like a fool, they're thinking I'm an idiot – the thing didn't work." Campbell tried one more time.

"Boom! It loaded up by some miracle – thank you god. The studio tracked Campbell's programmed LinnDrum part to tape. Disaster avoided and plain sailing from here on. Not quite…

"We went in and copied my demo, which was really hard because I had just done it off the top of my head," Campbell explained about recording the song with Henley. "All those guitar licks, I had to count them and put them in the right place because Don wanted it just like the demo. So we spent a week or more on the thing – overdubs, harmonies, synthesisers, guitars everything on there. And then Don comes in one day and says, 'I want to change the key.'

Campbell laughs at the memory, but his teeth are slightly gritted. It would take another week to track everything again in the new key of F♯ major. But, as with a lot of decisions in his musical career, Henley would be proved right.

"He, in his singing genius, had realised that if it was higher he could push it and get certain things out of it," noted Campbell. "And he was right. The Heartbreakers never did that – if we brought a song that was in A, it goes in A; sing it, make it work. We never thought to change the key for the voice but Don did."

Even after the song was mixed, the challenges continued. "We took the mix to the record company at 6 o'clock – ran over to the mastering and we were mastering it, and we put the tape up and as it was rolling by, I looked over and I saw the back of the analogue tape peeling off onto the floor in a pile," Campbell remembered. Everything stopped, and a staff member then surgically glued the backing onto the tape again. Phew.

Boys Of Summer launched Henley's solo career ahead of debut album Building The Perfect Beat and became a huge hit in 1984, winning Henley a GRAMMY Award in 1986 for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance.

For Campbell the success of the song addressed pressing concerns; it paid for a family home he was about to lose in a foreclosure. He considers it a stroke of luck, considering the obstacles Boys Of Summer had to overcome.

Meanwhile, Tom Petty would regret his decision in passing on Campbell's demo, though the record needs to be set straight on that.

Southern Accents was a notoriously difficult album to make for Petty and the Heartbreakers, and there's a story that the singer punched a studio wall during the 1984 sessions and broke five bones in his hand when he heard Boys Of Summer being played all over the radio. Only the first part is true. "

There wasn't a particular reason why I turned around and punched the wall… I was just frustrated," Petty revealed in the clip above about the incident during the 1984 sessions. Ear fatigue had set in as he listened back to mix after mix. "I thought the ends were going to be easier to tie up than they were," Petty said.

The injuries nearly ended Petty's career as a guitarist, but thankfully he would go on to recover. But the late legend did regret passing up Campbell's musical idea.

"'Years later Tom and I were mixing Don't Come Around Here No More in the studio and we go out to the car and listen to the mix on cassette like we used to do back in the day," he recalled on Brian Koppleman's The Moment Podcast in 2020.

"The two of us were sitting in the car and we turn on the radio and there's Boys Of Summer. I go, 'Oh!' and I change the channel. There it is again before I can even turn the cassette on. And he looks at me and goes, 'Boy, you know, you were really lucky with that. I wish I would have had the presence of mind to not let that get away.' That was a real brother moment we had."

But it's impossible to imagine the song now without Henley's vocals, melody and lyrics. It framed Campbell's music in a cinematic way that continues to attract listeners.

"The lesson there for you songwriter producers is when you hit a stumbling block, you've got to keep going – don't give up", reflected Campbell. "Keep pushing, pushing and working until you get it right. And eventually, all the elements will come together if you're blessed, and you'll have a hit record."

Rob is the Reviews Editor for GuitarWorld.com and MusicRadar guitars, so spends most of his waking hours (and beyond) thinking about and trying the latest gear while making sure our reviews team is giving you thorough and honest tests of it. He's worked for guitar mags and sites as a writer and editor for nearly 20 years but still winces at the thought of restringing anything with a Floyd Rose.

“Built from the same sacred stash of NOS silicon transistors and germanium diodes, giving it the soul – and snarl – of the original”: An octave-fuzz cult classic returns as Jam Pedals resurrects the Octaurus

“A purpose-built solution for bassists seeking unparalleled sound-shaping capabilities”: Darkglass Electronics unveils the Anagram Bass Workstation – a state-of-the-art multi-effects for bass guitar with neural amp model support and a 7” touchscreen