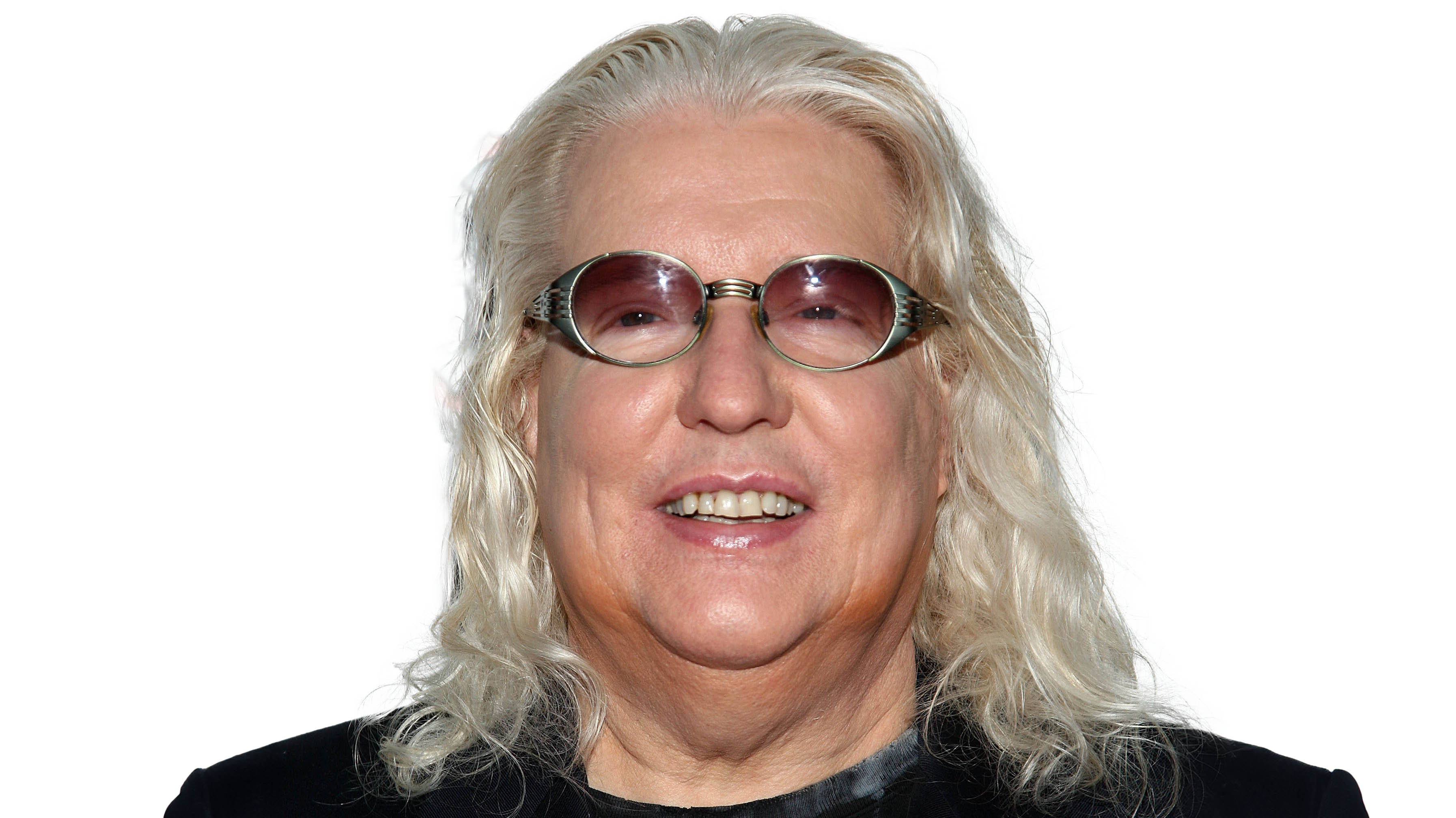

“Those arpeggios... That was the sickest thing I ever heard”: Yngwie Malmsteen on why guitarists should take inspiration from players of other instruments if they want to develop their own style

Plenty of players have impressed Malmsteen, but it was a solo violin performance that would have the biggest influence on his lead style

Many have tried but no one has managed to play the electric guitar quite like Yngwie Malmsteen. They broke the mould when they made him, or rather he broke the mould, exercising his expansive vocabulary of rococo classical phrasing within the framework of high-volume, high-spectacle rock guitar

But if the questions is how to follow in Malmsteen’s footsteps, maybe the first thing to do is stop thinking so much about the guitar. Speaking to MusicRadar in advance of his 40th anniversary live album, Tokyo Live, the effervescent guitar maestro had some advice for young players who are trying to develop their own style.

Malmsteen admits that he his share of guitar heroes, players he loves to listen to. But he never thought about any of them when he was workshopping his sound as a young, coltish player – it was classical violin.

And it doesn’t matter whether violin does it for you, or whether saxophone or a horn is more inspiring, the point is thinking like another musician, trying to interpret those ways of phrasing on the guitar, can open up a fresh perspective on the instrument.

Malmsteen argues that if you just listen to guitar players, you’ll end up sounding like a guitar player.

I love Angus Young and Eric Clapton. I love all the guitar players, all the greats. I think they are all brilliant, everyone from Brian May to Van Halen to Blackmore

“The thing is, I love Angus Young and Eric Clapton. I love all the guitar players, all the greats,” he says, getting more animated as he reminisces about the epochal moment, that inciting event in his life when he saw Jimi Hendrix torch his Stratocaster at Monterey. “I think they are all brilliant, everyone from Brian May to Van Halen to Blackmore. They are all fucking amazing. But they all seem to have one thing in common, which is not so strange in a way, but it’s that their biggest influences and favourite kinds of musicians growing up were other guitar players.

“Here’s the next part; the guitar players they were listening to were listening to another guitar player, and on and on and on. Very incestuous. And the only thing I see that’s a problem with this is that it’s a very specific box, a guitar mechanical box way of approaching a key – a B, a D, or whatever you want to play a solo in – and that’s the trap that you can fall into.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Malmsteen avoided this trap by accident or osmosis or a bit of both. The osmosis was his family’s doing. They were all musical. Violin, flute, opera. There was always music in his house.

“I wasn’t new to music,” he says. “My older siblings and uncles and stuff, there was always music around. I heard music theory and scales being practised and shit like that. I grew up with that.”

He didn’t want to play classical guitar. He wanted rock ’n’ roll, admitting that when he started playing guitar, what he wanted to do was “smash the guitar up like Jimi Hendrix”. In Malmsteen’s defence, he was seven years old.

The accident part came when he caught a televised performance of Paganini’s 24 Caprices for solo violin. That’s when the seed for Arpeggios From Hell was planted.

“I was 12 or 13 when I heard Niccolò Paganini being played on solo violin, on TV, and back in those days there were no VCRs, nothing, so I recorded it with a tape recorder from the speaker of the TV,” he says. “That is when I heard those arpeggios, which I’d heard played on keyboards but never on a stringed instrument. That was the sickest thing I ever heard.”

Malmsteen had the electric guitar. He had crossed the Rubicon, discovering distortion and overdrive along the way. He was playing all day, every day. When he started playing, he was listening to Eric Clapton over and over again even though he didn’t know who Clapton was.

“I didn’t even know who my favourite guitar player was,” he says. “My mum had a record called John Mayall [and the] Bluesbreakers. I didn’t know it was Eric Clapton playing guitar. I was seven years old. But I loved it. I loved it! I thought it was so fucking good, and so I listened to that all the time.”

And if you are familiar with the Malmsteen origin story, you’ll know the rest. The Pentatonic framework wasn’t doing it for him. Five notes per octave scale seemed too limiting. He heard Genesis’ Selling England By The Pound and it changed everything.

“For those who don’t know, those early Genesis records with Peter Gabriel were extremely progressive and just fucking amazing work. I heard it. I couldn’t believe it. The sound of the choirs, the Mellotrons, I didn’t know what they were but I loved it. Especially the keyboard player [Tony Banks], who was playing pedal notes.”

That was his eureka moment. His mother’s record collection had been recontextualised in the world of progressive rock.

“I heard that and I realised all that shit’s Bach, who I really loved,” says Malmsteen. “My mum had a million Bach, Vivaldi and Mozart records, and so I started listening to them. I already had a guitar with distortion and that’s how it happened, from a very, very young age.”

MusicRadar’s full interview with Malmsteen is coming soon. Brace yourself for strong opinions about Andy Warhol, virtuosity in art, and some wisdom in the difference between performance and practice, and the dangers in improv.

Tokyo Live is available to preorder and will be released on 25 April via Music Theories Recordings.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

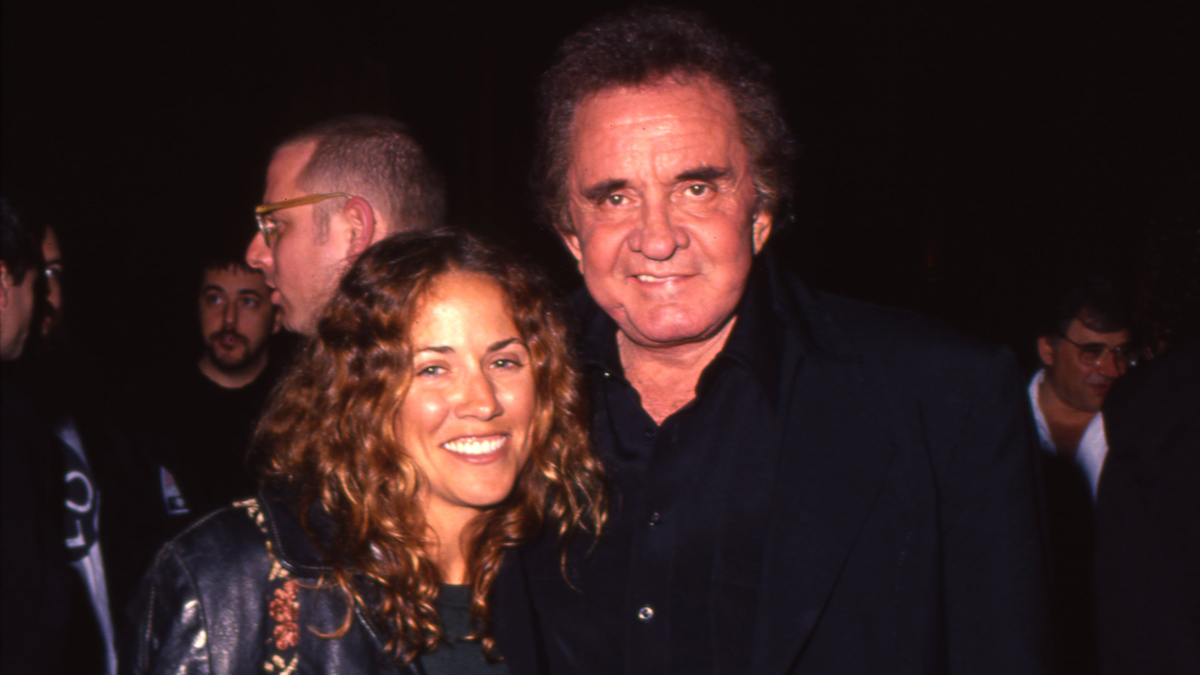

“It’s radical. It’s like magic. I get chills”: How Rick Rubin’s philosophy of chance led System of a Down to the first metal masterpiece of the 21st century

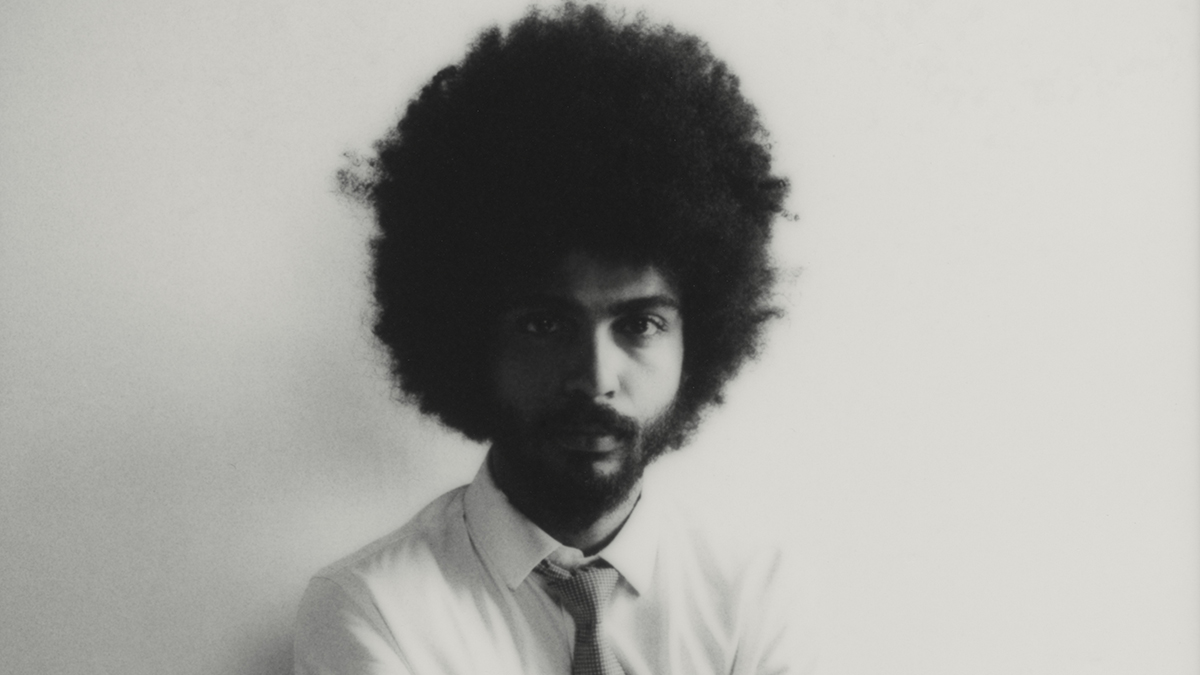

“I just treated it like I treat my 4-track… It sounds exactly like what I was used to getting with tape”: How Yves Jarvis recorded his whole album in Audacity, the free and open-source audio editor

![Gretsch Limited Edition Paisley Penguin [left] and Honey Dipper Resonator: the Penguin dresses the famous singlecut in gold sparkle with a Paisley Pattern graphic, while the 99 per cent aluminium Honey Dipper makes a welcome return to the lineup.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/BgZycMYFMAgTErT4DdsgbG.jpg)