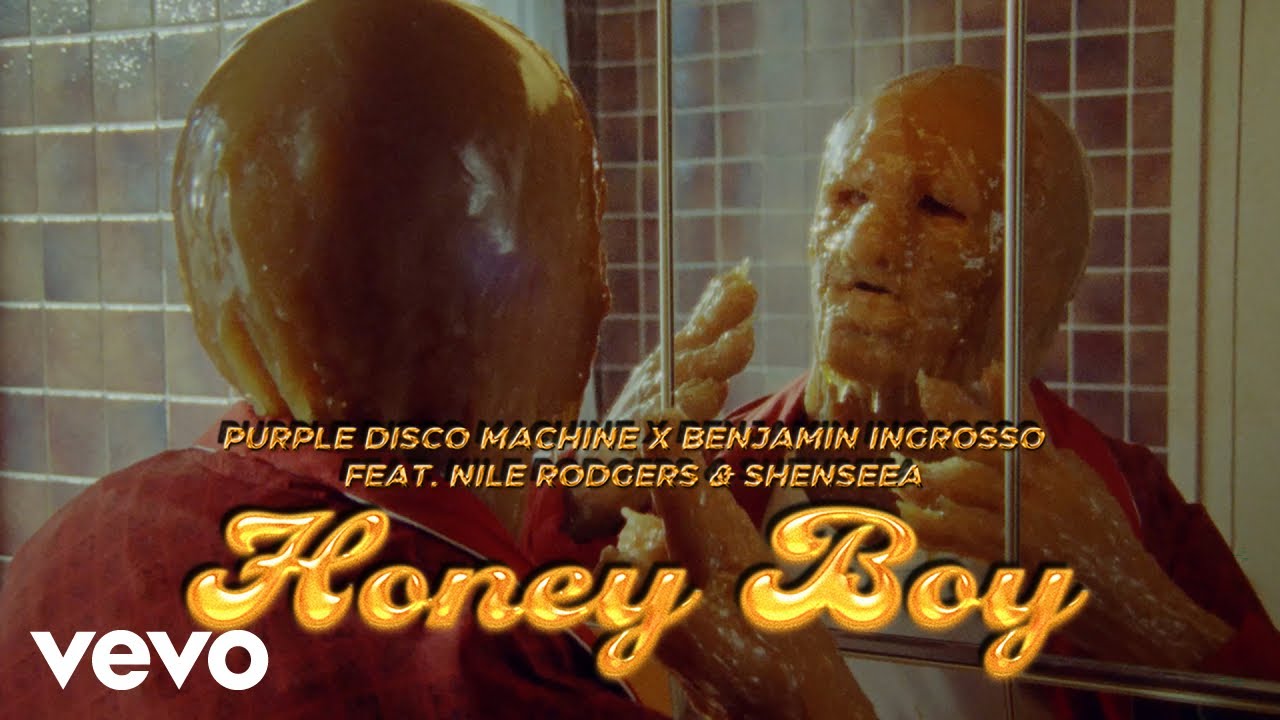

“When I got the email and started unpacking the stems, I was like a little kid unpacking my presents at Christmas”: Purple Disco Machine on working with Nile Rodgers for Honey Boy

On his third LP, Paradise, Purple Disco Machine’s Tino ‘Schmidt’ Piontek pays homage to ‘70s disco recording techniques

Thanks to his parents’ eclectic vinyl collection, Tino Piontek grew up listening to the prog rock of Genesis and formed a surprising adulation for Phil Collins.

However, after discovering the Dresden nightlife he soon became an advocate of house music, fell in love with Daft Punk and began producing with a limited hardware setup. By the mid-’90s, Piontek had become an active DJ, although his first Purple Disco Machine release would not appear until 2017 with his disco-drenched debut album Soulmatic appearing five years later.

Soulmatic immediately struck a chord with the disco fraternity and after the release of a second album, Exotica (2021), Purple Disco Machine was arguably one of the most successful contemporary house/disco producers of his generation. For his third album, Paradise, Piontek decided to pay tribute to the disco genre’s forefathers by adapting his approach to production.

Reaching for his contacts book, he invited live players and session musicians into the studio with a stellar cast of dance acts including Nile Rodgers, Jake Shears, Metronomy and Chromeo.

Your father was a record collector. How important was that to you becoming the artist you are today?

“Both of my parents brought me to music. It wasn’t something I’d just hear in the background on the radio but a hobby I actively spent my money on. Like you said, my father was a collector in East Germany at a time when it wasn’t easy to find music and you had to spend a lot of time, effort and money going to the black market in Czechia or Hungary to get vinyl. He had a big collection and played it all day, so I grew up with the notion that quality music has a certain value.”

When did you discover a sound or genre that was personal to you?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I found my own path around 15 or 16 when I explored techno and the whole electronic thing. The techno influence from Berlin became big in my area in the mid-‘90s and that was the first time that I felt a style of the music that had nothing to do with my parents – in fact, they hated techno. I was obsessed with DJs and watched Love Parade and the Mayday festival on TV, so I saved up money for my first turntables and started going to record stores.

“The problem was that I never really liked techno. I wanted to do something different and it was only when I heard Homework from Daft Punk that I discovered exactly the music I liked. It was a nice combination of techno, disco, funk and old-school hip-hop elements and I knew this was the music I wanted to make so I started sampling disco songs from my parents’ collection, just like Daft Punk did.”

You’ve said that “everyone has a connection to the ‘80s”. Do you have a bigger affinity to that era of dance or electronic music than late ‘60s or ‘70s disco?

There’s no soul in electronic music anymore. Everything sounds so compressed and there are no dynamics

“I have an affinity for disco music because I always liked its positive vibe and funky, happy spirit, but at the same time I liked that disco was on the border of being a little bit trashy and silly. Italo disco was huge in Germany – even bigger than Italy, so the italo disco legends were superstars here. I’m mostly obsessed with disco music from the late ‘70s when real people played real instruments and late in the decade legends like Giorgio Moroder combined that with electronic instruments. For me, this period was the best time for music because 50% of it was organic with a lot of soul and 50% was synthesizer and sequencer-based.”

Did you have any idea of how that music was made?

“I had no idea how Daft Punk did it or what gear they used. I bought some gear that I read other people had used but had no clue how to use it myself. The first things I bought were the Korg Electribe sampler series and a vocoder to try to replicate what I was hearing but I didn’t have the patience for it. I had a certain idea in mind, but no idea how to get there and got frustrated because I couldn’t get even close to the artists I was comparing myself to. Daft Punk were top of the league at the time, but my version was completely shit – it sounded shit, the mixing was shit and it was a crap copy of Daft Punk, but I did learn a lot about how synths and oscillators worked, which was important.”

Bringing things up to date, when did you begin to conceive the latest PDM album, Paradise?

“Before I even started working on Paradise I’d had the name in my mind for many years. For every person, paradise means something different – for some it’s a nice beach bar with a cocktail in your hand, but for others it may simply be home. My paradise is my house, my studio and my home town where all my friends and family are - any place I can just be myself. I thought a lot about the kind of music I wanted to make and invited almost every artist to my studio to write the songs in what I consider my paradise.”

How did that process evolve?

“Before I started working on the album, I listened to a lot of music from the ‘70s and ‘80s to decide what the signature sound should be. A problem for lots of electronic artists like me whose songs feature a lot of singers is that our albums sound more like a compilation. I needed to find that golden thread – a sound that goes from the first song to the last and discovered one or two synths to help me do that. One was the Minimoog for basslines and the Roland JX-8P, which was used on almost every song.”

Why did you turn to the Minimoog and JX-8P for ideas, in particular?

“I knew I wanted to use the Minimoog for basslines and sequences because it sounds super-warm. For the JX-8P, I just wanted to recreate the feeling I had from listening to lots of songs from the ‘80s and Hi-NRG producers like Bobby Orlando, which is when I discovered that a lot of musicians used the JX-8P at that time.

“The synth only has about 20 presets but each one can be connected to a song from that era and for people who are impatient, like me, you can get quick results without having to work with oscillators or filters for hours. I also used the Solton Arranger for basslines on almost every song because it’s a really rare Italian synth that was used quite a lot on italo disco records.”

You also started collaborating with, not just vocalists, but session musicians?

“First, I started working on song ideas with Matt Johnson, the keyboard player from Jamiroquai. He came to Dresden for a week to write lots of demos and after we had 30 or 40 I invited songwriters to my home to start writing lyrics and pitched demos to singers and instrumentalists that I’d mostly worked with before. By the end we had 40 or 50 songs, but the most complicated part was finding the 15 best ones. If a song wasn’t going to be released on Paradise I knew that I would never release it again as I’d rather start from scratch on my next album than use old ideas.”

We’re assuming Nile Rodgers is someone you’d longed to work with?

“It was important for me to work with people who share my love for disco, funk and analogue synths. I made a list of names I wanted to work with like Metronomy, who is one of my all-time favourite artists, Chromeo and Jake Shears. When I was in LA sitting with Chromeo in the studio, they had an even bigger collection of analogue synths than me and we spent half of the day talking about why they use what they do. It was like little kids sitting in Legoland having fun.

“Nile Rodgers was also on my list but we never reached out to him because it’s Nile Rodgers, so why should he work with me? Most of the songs on the album were also high-energy mid-‘80s stuff rather than the funky disco stuff that Niles is into. But after we recorded the live strings for the track Honey Boy, the whole thing turned into a super-classy disco song and I still had Nile on my list so I thought there still might be a 1% chance he would say yes.”

How did you get his contribution over the line?

“The label reached out to him, but after six months there was no reply so I thought, shit, let’s have one more try as my manager happened to be a good friend of Nile’s manager. I also wrote to Nile on Instagram and within two days he asked to hear the song and then instantly said that he loved it and recorded guitar licks for me. When I got the email and stared unpacking the stems I was like a little kid unpacking my presents at Christmas. The thought of Nile Rodgers recording stems for my song was surreal and then we finally met at the same event and he told me that every time he finishes his live set he plays the track Honey. To me, that’s crazy.”

Was your studio stocked enough for all the other live players that contributed to the album?

“My studio isn’t basic but the setup is perfect for me. I don’t have the space to record drums, we did those in Berlin, but I have my DAW and all the synths are routed to a huge Allen & Heath analogue mixer. I’m not a big piano player, but when I want to trigger a MIDI line, bass or chord on my DAW I can grab every single sound from every analogue synth because they’re all routed to the mixer via a MIDI patch. My analogue synths are basically like having VST plugins, for example, the Oberheim OB-X is on MIDI channel 8 and the Roland Juno-6 is on MIDI channel 9 etc. I also have Sequential’s new Prophet-10, which I absolutely love. It’s linked to all the other synths, so I can use it as a MIDI keyboard or to play sounds from a Juno-106 or Juno-60.”

Presumably, you’re using software for mostly audio effects?

“For me, software is important. My DAW is Cubase and every analogue synth is replicated with the same VST plugin. When I start working on ideas, I start with the VST version because I might not be at the studio or I want to get rough ideas down quickly before trying to adjust to using something like the Minimoog. Once I’ve found the perfect sound, I’ll go to the analogue synth and start recreating.

“On the effects side, 90% of the effects I use are digital. I used to use analogue effects units like the Space Echo but found that I had to spend too much time routing hardware units to all my synths. I have to say that the effects coming out of Steinberg are super-good. I use Valhalla for 95% of my reverbs and the Space Echo VST emulation or H-Delay plugin for delay.”

Would you say that VST effects are much closer emulations of hardware than their synthesiser counterparts?

“I did some A/B tests and most people would probably not be able to tell the difference between an analogue or VST plugin as the VSTs are so good right now. For my working process, it just feels more natural to work with analogue synths because the haptic is different and I like to work with knobs rather than a mouse.

“On the effects side, maybe I’m just a bit lazy and spend so much time on a sound that I don’t feel the need to go crazy finding the right delay. I also think that analogue synths sound richer, warmer and brighter. I learned years ago from a mixing engineer that if you have to adjust or EQ a sound too much because it’s clashing with other sounds, then maybe you should find a different one.”

It sounds like you have a very clear idea from the start of the types of sounds you want to use?

“When I work on music I have a 3D room in my mind and for every place in this room I try to find the right sound and give it its moment to shine. I’m not a big fan of layering 15 different sounds when you can use one that’s bright, rich and can be easily recognised. That applies to all sounds, whether it’s a bassline, brass or chords and so I spend most of my time looking for the right sound without using too many effects. The only effect I regularly use is chorus. For example, a chorus from the Juno-60 or 106 is the best and a digital chorus will never get close to those.”

Do you think a lot of electronic dance music suffers as it’s too focused on digital production techniques?

“There’s no soul in electronic music anymore. Everything sounds so compressed and the energy is always high-level but there are no dynamics. It’s why I prefer to mix my songs like a band with the singer at the front, the drummer further back etc rather than have everything in the middle fighting against all of the other instruments. Just like a band, if you place everyone or everything in the room wisely, the end result will sound better.”

How do you think you have evolved as a producer on this third album?

“Pre-Covid, I was always working on my own and never a big fan of sharing my studio with other musicians. After Covid, I learned the positive effect of working with people in the same room on a creative level and almost jamming like a band. I think you can hear that the music has more organic elements and is a bit more eclectic, which is why I like making albums.

“If you just release club singles it gets boring, but on an album I get to work on stuff like downtempo or R&B-influenced songs that I’d never release as a club tune. It’s been inspiring to say, okay, not every idea I have is the best and sometimes a musician’s idea is better than mine. Basically, the best idea wins and thinking like the classic disco bands did 30 or 40 years ago is how I’ll continue to evolve into the future.”

Purple Disco Machine's, Paradise, is out September 20 on Sony Music. For more information, visit the official website.