“When he got in front of the microphone, he sang his balls off. I’d never seen him happier”: How David Bowie stared down death itself for his final left-turn

Bowie foresaw how the world would react to his end - and artfully deconstructed his own myth with a last great masterwork

The death of David Bowie was a cataclysmic event for his legions of fans. Their passion had only recently been re-ignited following his return to rude creative health via 2013’s terrific The Next Day.

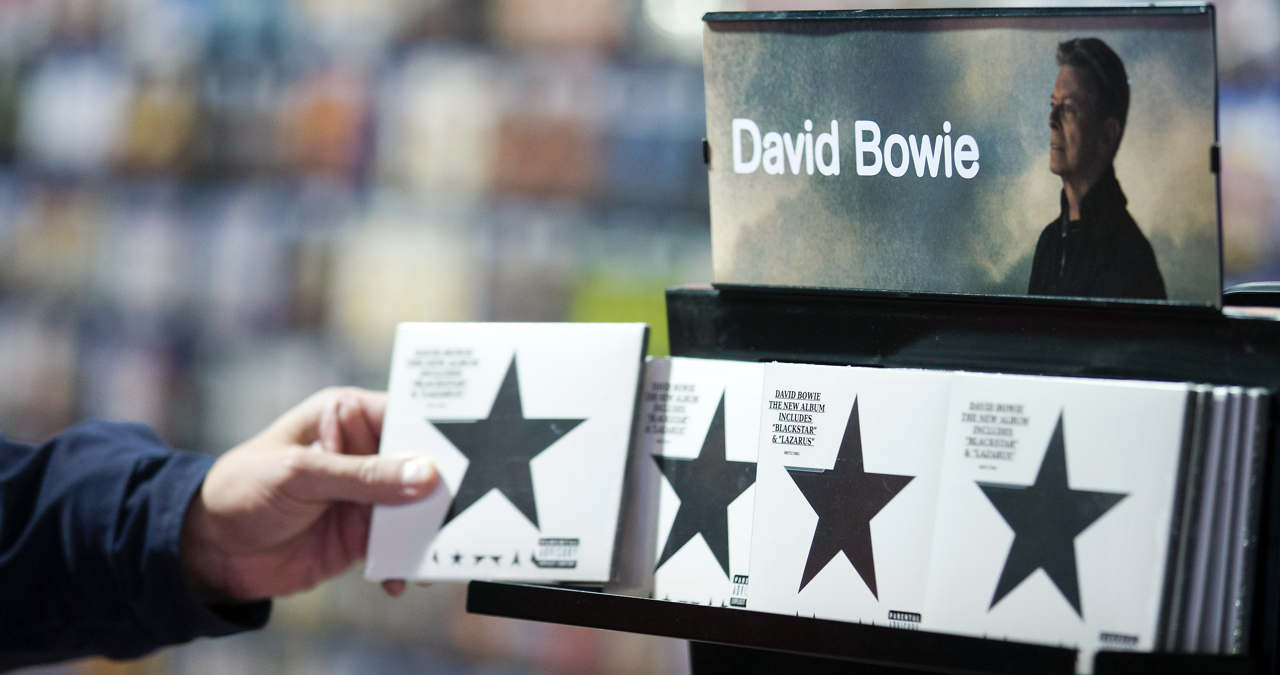

It was just a scant few days into their exploring its follow-up, Blackstar, when the unbelievable news hit the headlines.

Suddenly the record’s turbulent, ominous atmosphere made startlingly raw sense.

Across an album dense with portents of his own departure, one particular moment suddenly radiated with blinding clarity.

The Song: David Bowie - Blackstar

The Magic Moment: 04:41 - That extraordinary shift into the gorgeous mid-section - and Bowie’s prescient lyric.

The Origin

In the wake of his unexpected 2013 return The Next Day, David Bowie was feeling a renewed vigour for experimentalism.

Though The Next Day was a masterstroke of a comeback, its fourteen tracks parked Bowie’s more musically adventurous sensibilities in favour of tighter and more immediately accessible songwriting.

That was by no means a bad move for a high profile comeback record, but the man who had once held hands with Eno, and dove headfirst into a then-brand new ocean of synthesis on Low and “Heroes”, still had some surprises left.

The first evidence that Bowie was re-stoking his experimental fire came via the 2014 single, Sue (Or in a Season of Crime).

Recorded with jazz bandleader Maria Schneider, and featuring the expressive playing of saxophonist Donny McCaslin (soon to be a key creative collaborator), this choppy, swirling hedge-maze of a song foregrounded Bowie’s still astoundingly powerful vocals.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Its implacable arrangement also displayed that the spirit of musical courageousness, which had underpinned Bowie’s 1970s purple patch, was alive and well.

Giddy with anticipation for what the ever-unpredictable Bowie would do next, fans eagerly awaited album number twenty-six.

Once again signing up long-time producer Tony Visconti to helm the record, the 68-year old Bowie was keen to start recording.

But first, he was sadly faced with having to share some heartbreaking private news.

Visconti recalled that Bowie asked him for a private one-to-one meeting. During the meeting, David removed a woollen cap he was wearing to reveal that he had lost his hair and eyebrows.

This was a result of chemotherapy, following a devastating diagnosis of pancreatic cancer six months prior.

As one of his oldest friends and chief collaborators, Visconti was understandably upset.

But, Bowie reassured Tony that he was driven to defeat the terrible disease.

“He told me he’d been having chemotherapy,” Visconti recalled to Music Week. “The next day he told the band and said, ‘We’ll just get this out in the open so we don’t have to talk about it again’. Apart from the shock of those first 10 minutes, the album went on without [us] discussing it again and he was in great form.”

A quartet of jazz musicians - regular accomplices of Donny McCaslin - had been enlisted (alongside Donny) to further map out the shadowy musical territory that David wanted to explore.

Simultaneously excited by the opportunity to work with Bowie and shocked at this alarming turn of events, the band - McCaslin, Jason Linder, Tim Lefebvre and Mark Guiliana - respected Bowie’s wishes for the situation to remain private.

Putting the situation to one side, the musical team immersed themselves in the project.

“Basically the first day in the studio, before we played a note, he said to me, ‘I want you to go to wherever you’re hearing. Don’t worry about how this will be classified genre-wise: rock, jazz, whatever. Just feel completely free to do whatever you want.’” Donny remembered in an interview with SF Sonic. “It was great to hear it from him. I couldn’t have asked for a more freeing creative environment to step into.”

Though direct discussion of Bowie’s condition was off-the-table, Bowie’s songwriting was rife with themes that explored his own relationship with mortality.

From the pulsing frailty of Lazarus, the weary regret of Dollar Days and the perturbed, histrionic anger of Girl Loves Me.

“There were days he couldn’t come in,” Visconti told The Guardian. “But when he got in front of the microphone, he sang his balls off. I’d never seen him happier.”

Blackstar’s nearly ten minute-long, through composed title track was the album’s most ambitious work. Within its three sections, Bowie grappled with life, death and the weight of the mythology he’d fabricated over the course of his fifty-year career.

The song’s initial part was shaped around its skittering 5/4 beats (which often seem un-anchored from a fixed tempo), McCaslin's howling sax and Bowie’s solemn, mournful vocal that is intoned via a monk-like chant.

Referencing the Villa of Ormen’’s ‘solitary candle’ where ‘only women kneel and smile’, Blackstar’s first section sets an ominous scene. It's akin to walking into a room in a large house, only to find some sort of cult’s ritual sacrifice underway.

But, as this murky, tense part reaches an anguished crescendo via McCaslin’s saxophone, it crumbles to dust.

Gradually taking its time to re-shape itself into a more stable synthesised chord sequence, Blackstar’s mid-section finds form. Suddenly, a recognisably human Bowie emerges from the ruins.

Sounding vulnerable, and with a hint of sadness in his voice, Bowie sings an achingly beautiful melody, delivering a lyric that asserts the central tenet of the album:

Something happened on the day he died

Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside

Somebody else took his place, and bravely cried

(I'm a blackstar, I'm a blackstar)

As the lyric progresses, Bowie takes a hammer to his own status as a cultural icon

Just go with me (I'm not a filmstar)

I'ma take you home (I'm a blackstar)

Take your passport and shoes (I'm not a popstar)

And your sedatives, boo (I'm a blackstar)

You're a flash in the pan (I'm not a Marvel star)

I'm the great 'I am' (I'm a blackstar)

As the middle section builds into a central, lush chorus, Bowie wrestles with just who, or rather what, he has become.

Within the lyrics, Bowie decries his status as a cultural icon. He’s neither a ‘popstar’ or a ‘filmstar’, nor is he any of an array of other fascinatingly oblique terms; (‘I’m not a white star’, ‘I’m not a star’s star.’)

The truth is as at last revealed.

David Bowie’s final incarnation is, who he’s always been. A blackstar.

Why It's Brilliant

This middle section is, in our view, one of the most beautiful pieces of music in Bowie’s exceptional songbook, even taking into account the majesty of his most celebrated gems, such as Life on Mars?, “Heroes” and Ashes to Ashes.

Not only is it an unexpected pivot from the song’s more experimental opening section (demonstrating Bowie’s still brilliant knack for musical audacity) but thematically lays out the key artistic battleground that the rest of the album would continue to navigate.

While the numerous interpretations of just what a ‘blackstar’ actually are can keep many a Bowie fan up long into the night, in the context of the song, it seems that Bowie is using the term to make sense of his own relationship with his life's work.

Was David Bowie ever ‘really’ a rock-star? (or, was that Ziggy Stardust?)

In an artistic career rife with the disposal of masks and facets, this final shade - David Bowie himself - is revealed to be nothing but a blank slate. He's a canvas on which so much has been painted.

The allusions to ‘the day he died’ are tempting to read as prophetic. And, if we choose to read the song this way, Bowie seems to be pondering how much the overwhelming shadow of his own mythology will conceal once he was gone.

With the prospect of death a very real concern for him at the time, it’s understandable that David would be ruminating on how much the artifice would hide the man.

Ziggy Stardust, the Thin White Duke, Major Tom. All masks worn by David Bowie, hide the essential truth that at the centre of that self-built lore - even stripping away Bowie himself - stands a real, mortal David Jones.

But who was this essential human? Can we ever really know?

‘I can’t give everything away’ Bowie sings at the very end of the record. And maybe that’s ok.

These thought-provoking themes took on a whole new poignancy post-death, when the relentless TV coverage, op-eds and documentaries immersed viewers in Bowie’s legacy.

The art vs artist tension was brought to the fore further in Johan Renck’s exceptional video for the title track. It teasingly incorporated many visual allusions to Bowie’s past. Most prominent of which was the dead astronaut who, once the helmet’s visor is lifted, is revealed to have a bejewelled skull.

A worshipped figure, misunderstood, and very far from home.

It seems too tempting to not interpret this figure as Major Tom - the protagonist of 1969’s Space Oddity. Bowie’s first hit.

This concept was sketched by Bowie and given to Renck prior to the video shoot.

While Blackstar absolutely contends with mortality as a major theme, it’s heartening to know that the perpetually optimistic Bowie actually remained hopeful of continued life despite the diagnosis.

”He was planning on recording new music with us,” Donny McCaslin told SF Sonic.“The last time we talked it was on the phone and he said he was writing new music and wanted to go back to the studio in January with us. Blackstar, obviously, has such heavy themes of mortality and part of the narrative around the record was that it was his goodbye gift to everybody, and while I think that’s true it’s one of those situations where multiple things are true. It’s a great way to have left his mark as an artist, but at the same time he was still moving forward and we were going to record some new music.”

Sadly, with David Bowie’s death on January 10th 2016, Blackstar would remain his last - and perhaps his most eternally intriguing - word.

It’s the final piece in the sprawling, fascinating jigsaw left by one of music’s greatest ever artists.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.