“We were always going to try to break boundaries and try new things”: It was the first No.1 pop single to feature rapping - and it came from Debbie Harry and Blondie

“Some people loved it, and some people hated it,” recalled drummer Clem Burke

There comes a time in the lifespan of most bands where your survival rests on your ability to embrace change and create something innovative and new for the shifting marketplace. For New York band Blondie such a moment came in 1980, with the release of their fifth album Autoamerican.

The album spawned two huge hits.

The first was The Tide Is High, a catchy and upbeat cover of the Paragons’ 1967 Jamaican rocksteady song.

The second was Rapture, a song that merges disco, hip-hop, funk and new wave

Rapture would go on to become the first No. 1 pop single to feature rap music. It would also set the bar for what a pop single could be at the advent of the MTV age.

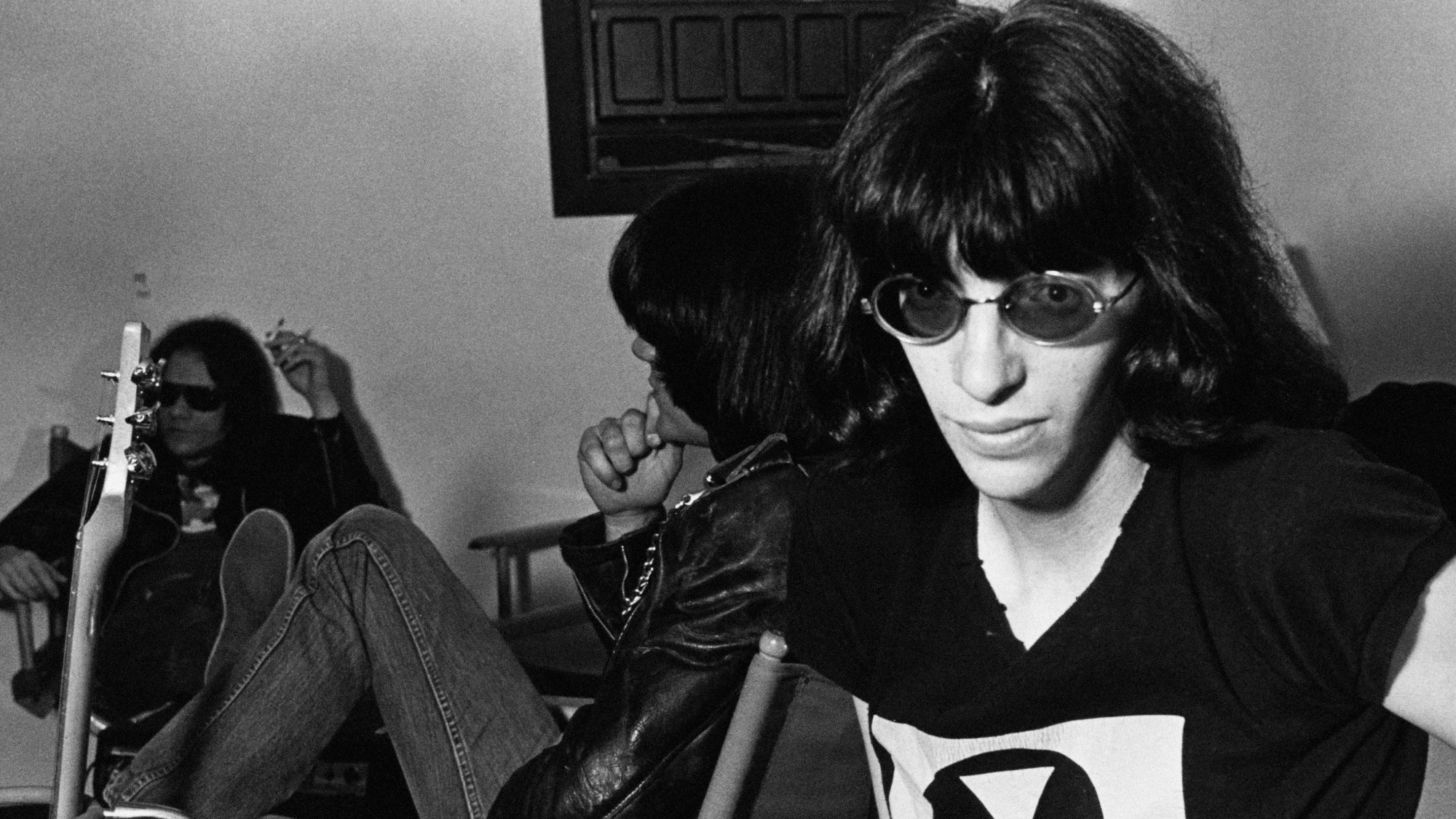

By the time Blondie released Rapture, they had become one of the biggest pop bands in the world.

While the first two albums, Blondie (1976) Plastic Letters (1978) melded strong melodic hooks with a post-punk sound, the third album Parallel Lines (1978) thrust them into the mainstream. On that album, they teamed up with Australian producer Mike Chapman, who helped them forge hits such as Hanging On The Telephone, Picture This, Sunday Girl, One Way Or Another and the disco-infused classic Heart Of Glass.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Blondie’s fourth album Eat To The Beat yielded the hits Dreaming, Union City Blue and Atomic, but by then there was turmoil and conflict within the band, as Chapman himself noted.

“The music was good,” he said, “but the group was showing signs of wear and tear. The meetings, the drugs, the partying and the arguments had beaten us all up, and it was hard to have a positive attitude when the project was finally finished.

“Was this the record that the public was waiting for, or was it just the waste of seven sick minds? I had never experienced this kind of emotional rollercoaster before, and I have never forgotten the sounds, smells and tastes that came with it.”

By fifth album Autoamerican the band’s creative linchpins, vocalist Debbie Harry and guitarist Chris Stein, were planning a radical reinvention of their sound, and Rapture was one of the songs that would really nail their colours to the mast.

Most music aficionados of the late ’70s would be aware of the seismic creative influence of the East Coast hip-hop scene, whose Big Bang moment is widely acknowledged to be a back-to-school house party thrown by DJ Kool Herc, in the Bronx on 11 August, 1973.

At this event, Herc extended the instrumental beat, or backbeat, to keep people dancing for longer. Then he began rapping over it.

Hip-hop and its attendant culture was born, and by the late 70s Herc and artists such as Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa and the Sugar Hill Gang were hugely influential figures within the burgeoning East Coast hip-hop scene.

Debbie Harry and Chris Stein were friends with New York hip-hop artists such as Fab 5 Freddy in the late 1970s. Freddy was a hugely influential advocate for early hip-hop culture.

One night in 1978, Harry and Stein accompanied him to a rap event in the Bronx and were enthused by the creativity and the skill as DJs spontaneously rhymed lyrics over beats while others lined up for their chance at the mic to freestyle rap.

Harry and Stein went to more events, and in late 1979 they decided to combine the rap music they had heard in the Bronx with Chic-inspired disco music.

“We were always trying to be creative and do something a little different,” Harry told Jim Beviglia of American Songwriter magazine in August 2021. “That was always sort of an understanding between me and Chris that we were always going to try to break boundaries and try new things.”

To mix things up further, Mike Chapman suggested that the band record the Autoamerican album at the famous United Western Recorders studio in Hollywood, California, a decision lamented by Stein in an interview with the New York Post: “Every day, we get up, stagger into the blinding sun," he quipped.

But other band members were elated by spending two months in the California sunshine.

“We all had hot rods and Cadillacs,” drummer Clem Burke told American Songwriter magazine. “It was at the peak of the band after the success of Parallel Lines and Eat To The Beat. It was a whole different environment being out in LA. Just going to that great studio United Western, where the Beach Boys did Pet Sounds. I was definitely acutely aware of the history of the studio.”

Sessions got under way in early 1980. The aim of the record was to boldly meld different styles of music, and Rapture’s fusion of rap and disco epitomised this creative direction.

Blondie and Chapman managed to work up a funky disco groove on Rapture that evoked just the kind of sound that rappers loved to sample.

The track is anchored by a natural live drum groove from Clem Burke in the studio while bassist Nigel Harrison lays down a deft and infectiously fluid bass line. Crisp funky guitar rhythms and handclaps pervade in the mix.

There’s also a haunting church-like feel, courtesy of some tubular bells that the band’s keyboardist Jimmy Destri discovered in the back of the studio at Universal Recorders. These became a defining feature on the track, the warmth of their sound offsetting the crisp precision of the rhythm section.

The song, with its six-and-a-half minute running time, is essentially made up of two distinct halves, the first being the two verses of the main song and the second being the extended rap coda.

The first section features one of Debbie Harry’s most captivating vocal takes, with her powerful top line melody soaring above disco-funk guitars.

Lyrically, the first two verses focus on familiar disco themes, such as the euphoria, liberation and frisson of the dancefloor: “Toe to toe, dancing very close/Barely breathing, almost comatose/Wall to wall, people hypnotised/And they're stepping lightly/Hang each night in rapture”.

At 1:57 the singing stops and at 2:10, Harry’s rapping begins as she shouts out Freddy and Grandmaster Flash: “Fab 5 Freddy told me everybody's fly/DJ spinnin' I said, ‘My, My’/Flash is fast, Flash is cool/France Soir c'est pas Flash et Nous Deux/François c'est pas, Flash ain't no dude.”

As the track goes on, Harry makes a reference to graffiti – “Paint a train, you’ll be singing in the rain” – before name-checking TV Party, the public access TV show that Chris Stein hosted for a few years.

She then launches into a story about a man from Mars who eats cars and bars. “You eat Cadillacs, Lincolns too, Mercurys and Subaru…”

“Chris wrote the part about eating the cars,” Harry recalled in American Songwriter magazine.

The track then takes on a momentum of its own. At 3:22, punchy horn stabs featuring top saxophone session player Tom Scott enter the mix. For over a minute the whole band just grooves and cooks before Harry’s rapping re-enters at 4:35 for the outro.

Just when you’re mentally gliding down for a fade-out, a thick, growling overdriven guitar thwacks you from your reverie at 4:55.

The horns intersect with twisted bursts of lead before it drops back down to the nimble, infectious groove. It’s audacious and invigorating.

Debbie Harry has said that she wishes she had had another chance to record her rap part. “I didn’t feel terribly confident,” she told Jim Beviglia in American Songwriter magazine in August 2021. “I liked the idea of it but I wasn’t really sure about that performance. It was like the first take.

“He [producer Mike Chapman] was just so relieved to get it. And I said, ‘Okay, that’s it’. But I think it would have gotten better. I know I do it differently now with experience behind me.”

Opinions were divided on the rap section.

While some found it inventive, others deemed it ineffectual or just plain embarrassing.

But in some ways, the rap succeeds precisely because Harry chose not to try and emulate the rapping she and Stein had first heard in the Bronx. Rather, she attempted to reinterpret it in her own way.

As Tom Breihan of Stereogum put it in April 2020: “It’s a stretch to refer to what Debbie Harry does on Rapture as rapping. Instead, she does a sleepy and absurdist deadpan spoken-word thing, icily muttered half on the beat. That routine would’ve gotten her weird stares at any block party in 1981. And yet it works. It’s an ace piece of culture-vulture silliness that nobody else thought to try first.”

On 25 November, 1980, Blondie released Autoamerican, the album they had spent two months in California recording. When they delivered the album to their record label Chrysalis, the company was underwhelmed.

“When we gave the record to Chrysalis, they said they didn’t hear any singles on it,” recalled Chris Stein.

It was a spectacular misjudgement by the label. Both The Tide Is High and Rapture would hit No.1 on the US chart.

In the run-up to the release of Autoamerican, Clem Burke invited some close friends round to listen to the album. When Rapture came on, there was complete shock.

“I always remember that the first time I played Rapture, I had a little listening party at my loft in New York,” Burke told Jim Beviglia of American Songwriter magazine. “Playing the album through to my friends, they were like, ‘What the heck is this?’. When Debbie did the rap on Rapture, their jaws were on the floor.”

Many critics loathed the song, but the public largely lapped it up.

“I think the reaction to Rapture was that some people loved it, and some people hated it,” recalled Clem Burke, “which is probably always a good sign.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“For some reason, the post office shipped your guitar to Jim Root of Slipknot”: Sweetwater mailed a metal fan's Jackson guitar to a metal legend

"No one phoned me. They never contacted me and I thought, 'Well, I'm not going to bother contacting them either'": Ex-Judas Priest drummer Les Binks has died aged 73