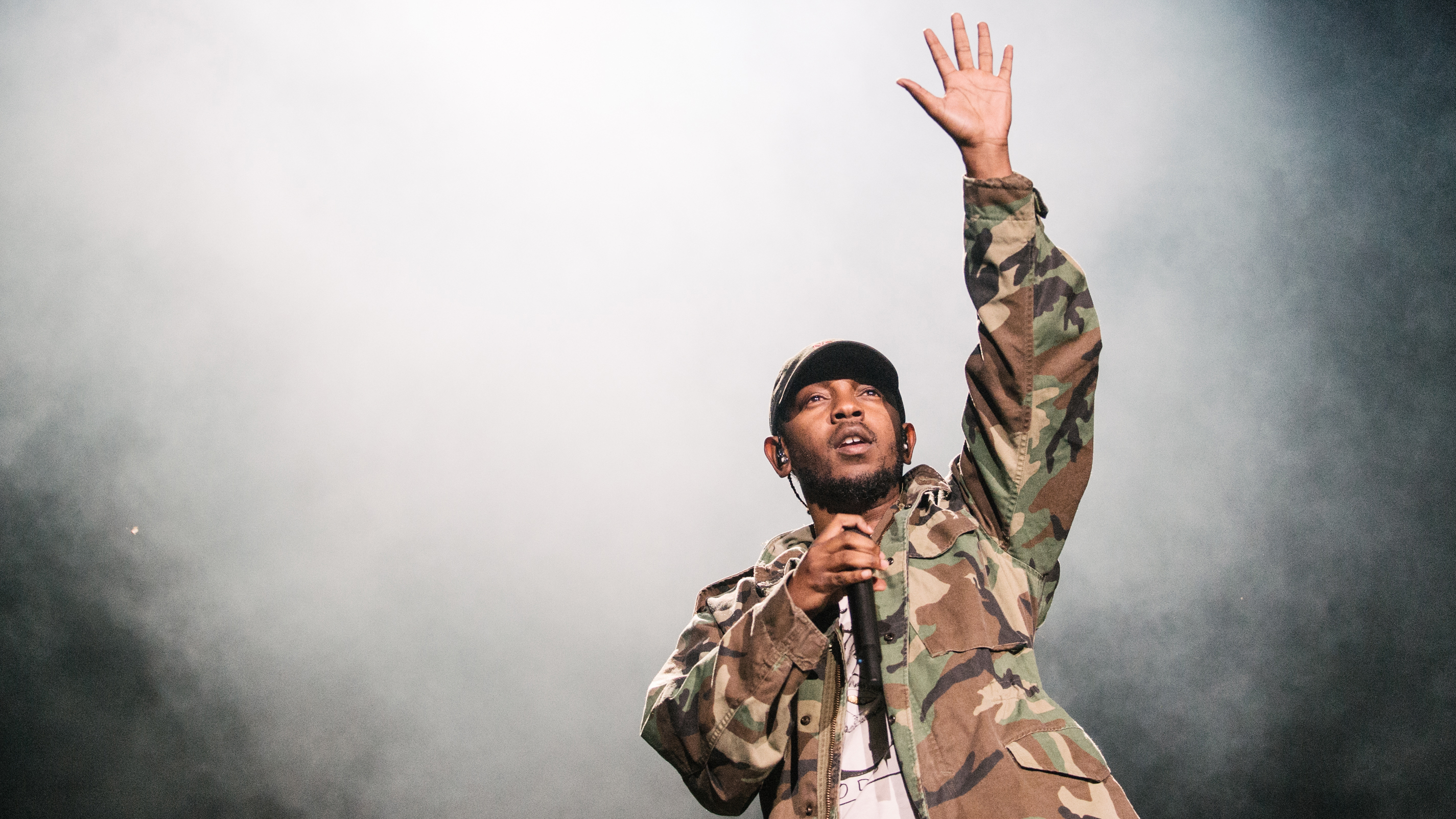

“There's only one person on Earth who could turn a highly conceptual, fiercely political, free-form jazz-rap fusion record into a global hit”: Making Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly

10 years on from the release of Kendrick's seminal Grammy-winner, we look back at how TPAB was made - and why it still resonates even more deeply a decade later

There's only one person on Earth who could turn a highly conceptual, fiercely political, free-form jazz-rap fusion record into a global hit.

Five Grammy wins, 4x Platinum status, 9.6 million first-day streams (a Spotify record) — the awards and accolades quickly piled up following To Pimp A Butterfly's release on 15 March 2015, and ten years down the line Kendrick Lamar's second studio album is widely considered one of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time.

While Lamar's 2012 debut good kid, m.A.A.d city fleshed out the LA rapper's background and origin story with visceral, cleverly-structured narratives rooted in the realities of Compton street life — cementing his reputation as one of the world's most exciting young rappers — TPAB took things to the next level conceptually and sonically.

The project's scope and ambition was huge. To Pimp A Butterfly meshed together a wide array of jazz, soul, and funk influences to create a fluid, experimental sound that connected modern hip-hop to the rich and varied African-American cultural movements that preceded it.

This conscious sonic staging helped Kendrick shine a light on the institutional racism and political tensions of the United States in 2015, creating a soundtrack for the Black Lives Matter movement with hugely impactful singles like 'Alright' and 'The Blacker The Berry'.

Forming a spine throughout the record are fragments of a spoken word monologue narrated by Kendrick, gradually pieced together into a cohesive passage about the strains of navigating the transition from Compton to stardom. These fractured moments hinge around a real-life meltdown he had in a hotel room on tour, brought on by an intense disconnect between his roots and his current reality. "The feeling was, 'How am I influencing so many people on this stage rather than influencing the ones that I have back home?'" he told NPR.

In lines like "I remember you was conflicted / Misusing your influence" this poetic refrain communicates the album's overarching narrative: Kendrick's efforts to avoid being "pimped out" by Uncle Sam, the personification of American capitalism who threatens to lure him away from core values and principles and alienate him from his community using materialism and fame. Through tracks like i Kendrick breaks free of these vices, transcending the caterpillar's cocoon to become the figurative 'butterfly' of the album title.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"The hook of i is "I love myself" — no song can stand the test of time like a declaration of self-love, it's food for the soul," says Yousef Srour, an LA-based music writer who has covered Kendrick's work extensively for sites like Passion of the Weiss. "Those songs, which promoted self-love and love of one's community, became anthems to bring everyone together. You'd hear Alright at protests and campaign rallies, it uplifted people. You could feel turmoil in America, and this was a statement: Kendrick was taking the power back."

Key to amplifying this musical show of power was the cast of creatives Lamar employed to construct this album's unique sonic identity. This included jazz saxophonist and founder of the West Coast Get Down collective Kamasi Washington, bassist and vocalist Thundercat, producer and multi-instrumentalist Terrace Martin, and vocalists like Bilal and Anna Wise, as well as long-time collaborators like the experienced beatmaker Sounwave (who played a crucial role in recording Kendrick's 2022 confessional album Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers).

Kendrick's album broke many of these artists into the mainstream, giving them the chance to shine and subsequently build their own impressive careers off the back of it. After the record's release, Kendrick told Grammy.com: "I knew from the jump I had to get the best musicians in my own backyard from L.A. — Sounwave, Terrace Martin, Kamasi, Robert Glasper. Knowing what all these other artists put into making this record, it's a little more homegrown."

Assembling at Dr. Dre's No Excuses studio in LA, this collective, led by a hands-on Kendrick Lamar, was given ample time and resources to construct the project. Dre took a backseat, leaving the album's mixing to Derek Ali, also known as Mixed by Ali.

"He took me under his wing and showed me a lot of techniques that you can't learn in books. I went from Pro Tools LE with an Mbox to an SSL 400 overnight"

"Kendrick had his own sound, so when it was time to mix that album Kendrick said that he wanted me to mix it," Ali told Sound on Sound. "Dre appreciated that, because he liked a young guy who wanted to learn the art of engineering and mixing, instead of wanting to become a producer or a rapper. He took me under his wing and showed me a lot of techniques that you can't learn in books. I went from Pro Tools LE with an Mbox to an SSL 400 overnight."

This analogue SSL Desk was the same desk used to craft legendary hip-hop albums like Dre's The Chronic and Eminem's Slim Shady LP. Discussing the lessons he learned from the hip-hop icon, Ali recalled watching Dre sculpt a single snare sound for an hour, explaining "he works analogue, he works on a big mixing console… he sounds out from the computer every individual sound, kick, drum, snare, vocal, background, hi-hat… every sound needs to sit in its own respective pocket sonically."

This was the technique Ali employed on TPAB, manually mixing the album in order to "feel like I am touching the music and I am part of it," in his words. He was one of several in-house musicians used by Kendrick's label Top Dawg Entertainment to support Lamar and take his second album up a notch. One of the most crucial figures in the whole process was Terrace Martin.

In an interview on the R&B Money podcast, Martin described Top Dawg Entertainment as "masters of getting a bunch of borderline insane crazy people in one room, that all have loud voices, and figuring out a way of us all following a common goal. I've never seen leaders like Top [aka CEO Anthony 'Top' Tiffith] and Punch [label president Terrence Louis Henderson Jr] in my life."

Numerous contributors have praised TDE's top brass for the way they oversaw Kendrick's creative process, and the discipline they instilled when it came to knuckling down for studio sessions and not inviting friends and girlfriends to drink and party on recording time without permission from up top.

"He's always in the studio giving you ideas, and his instincts are incredible"

While there's a rawness to TPAB, Martin's assertion that it's "not a garage, earthy, inexpensive album at all," is bang on. The record is packed with rapid, intense percussion sessions, manic vocal performances, and quickly climbing keys, but a lot of background work needed to be done to allow this loose approach to take hold. "Kamasi [Washington] was writing for strings while we've got union strings players waiting all day to get charts," said Martin. "To be that free is so expensive!"

In 2017, Kamasi Washington reflected on Kendrick's attention to detail, and the proactive way he interacted with other artists in the studio. "He'd be sitting there watching me write string parts," he told Pitchfork. "Not a lot of people would care. They would be like, 'Show it to me when it's done.' But he's always in the studio giving you ideas, and his instincts are incredible. He'll hire people to do the style that they really want to do and then take all this genius poured into this pot… it's a real type of humility—not humble for any philosophical purpose, but a true humility."

Perhaps that humility came from the fact that TPAB pushed beyond the confines of what anyone within the US hip-hop scene was comfortable with doing at the time. The LA rapper went into the process as a visionary and an extraordinary songwriter, but he was no jazz expert. He needed people that were more familiar with this world. That being said, he evidently had a natural instinct for the textures and patterns of US jazz and blues.

"This kid don't know no Coltrane records… that has to be ancestral recall"

"[Kendrick] was heavily influenced at that time by jazz," added Terrace Martin, reflecting on the creative process. "I was like 'you rapping like Freddie Hubbard, you got one song where you sound like Woody Shaw, you got one song where you sound like classic Clark Terry!" He recalls transcribing a Kendrick vocal pattern and comparing it with old John Coltrane transcriptions, and becoming stunned by the similarities. "This is deep," he said. "This kid don't know no Coltrane records… that has to be ancestral recall."

Interestingly, it's a connection Yousef also brings up, totally unprompted. "When Coltrane says "A love supreme" in the introduction [of the eponymous track], the words feel like they just come out of his body spiritually," he says. "That's what it's like when Kendrick's rapping on these [TPAB] beats, it's free-form, he's rapping like these words are just coming out of him."

For example, there's the tortured scream at the start of u, and the manically-repeated refrain "Loving you is complicated" which bursts out of Kendrick's mouth in inconsistent stutters and starts as the track progresses. There's the heavy breathing that opens For Sale? Interlude, and numerous other moments that bring a spontaneous and flawed humanity to the album.

These vignettes are painted over richly textured instrumentals that pay homage to pioneering Black American artists like James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Miles Davis, and Parliament-Funkadelic, with meandering sax melodies, soaring, expressive vocals, and tight and funky percussion sequences.

But compared to many other classic hip-hop records, TPAB is fairly light on sampling. Kendrick focused on letting his team of musicians flex their creative muscles in a live setting. "We [made] a lot of records from scratch," Kendrick told Grammy.com. "There were certain times where I'd just write to a drum loop over and over and over again till it felt right. I wanted to make this record dense. I didn't want to actually make it for radio… I want you to go to sleep playing these songs back in your ear because what happens is you grow to understand it more… ten years from now you'll always find another jewel in there."

That analysis rings true for Yousef. "Being able to grow and understand culture more, you realise Kendrick was pulling from all these different places, it's genius. When you sit down with TPAB, and you're immersed in the world, you're really able to understand the choices and influences they're going for.

"It wasn't until recently that I heard the original Isley Brothers songs sampled on i," he continues. Here he's talking about the lightly strummed chord pattern that forms the basis of their single 'That Lady', first recorded in 1964 but made famous by a heavier 1973 remake featuring woozy, distorted wah-wah guitar solos peppered across the track's funky breaks.

Speaking to Jimmy Kimmel about this particular sample, Kendrick explained: "Those are the records that my parents played when I was growing up, in the 90s they played nothing but Isley Brothers, Temptations."

"Considering the social tension in America, the political tension in America, that's what rap music needed, and he stepped up to the plate"

That nostalgic funk influence is essential to a transition that takes place towards the end of the album: having pushed his way through complex, muddy issues of fame, fortune, isolation, racial and political tension, and exploitation, developing a tighter grasp of his place in the world, Kendrick lands on a breezier, more life-affirming tone underlining the culmination of this fascinating personal journey.

Rubberstamping the progress made, the record ends with a posthumously constructed conversation with the late LA hip-hop legend Tupac Shakur (using snippets taken from a 1994 interview). Aligning yourself with such an icon on your second album is an ambitious decision for a hip-hop artist to make; a decade later, with Kendrick Lamar having solidified his status as the greatest rapper on the planet, it's even more powerful.

"To Pimp A Butterfly has aged perfectly," says Yousef. "He captured what LA sounded like in 2015, and what it sounded like in the decades before. People in rap music love narratives, and this album gave Kendrick the narrative that a lot of people needed from an artist at the time. Considering the social tension in America, the political tension in America, that's what rap music needed, and he stepped up to the plate."

Fred Garratt-Stanley is a freelance music, culture, and football writer based in London. He specialises in rap music, and has had work published in NME, Vice, GQ, Dazed, Huck, and more.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.