“The album was played in LaGuardia Airport for a brief period, but travellers said it ‘induced unease’ and sounded like funeral music”: A music professor breaks down Brian Eno's Ambient 1: Music For Airports

Following the release of Gary Hustwit's long-awaited Eno documentary, our resident music prof puts the fabled producer's most celebrated release under the musical microscope

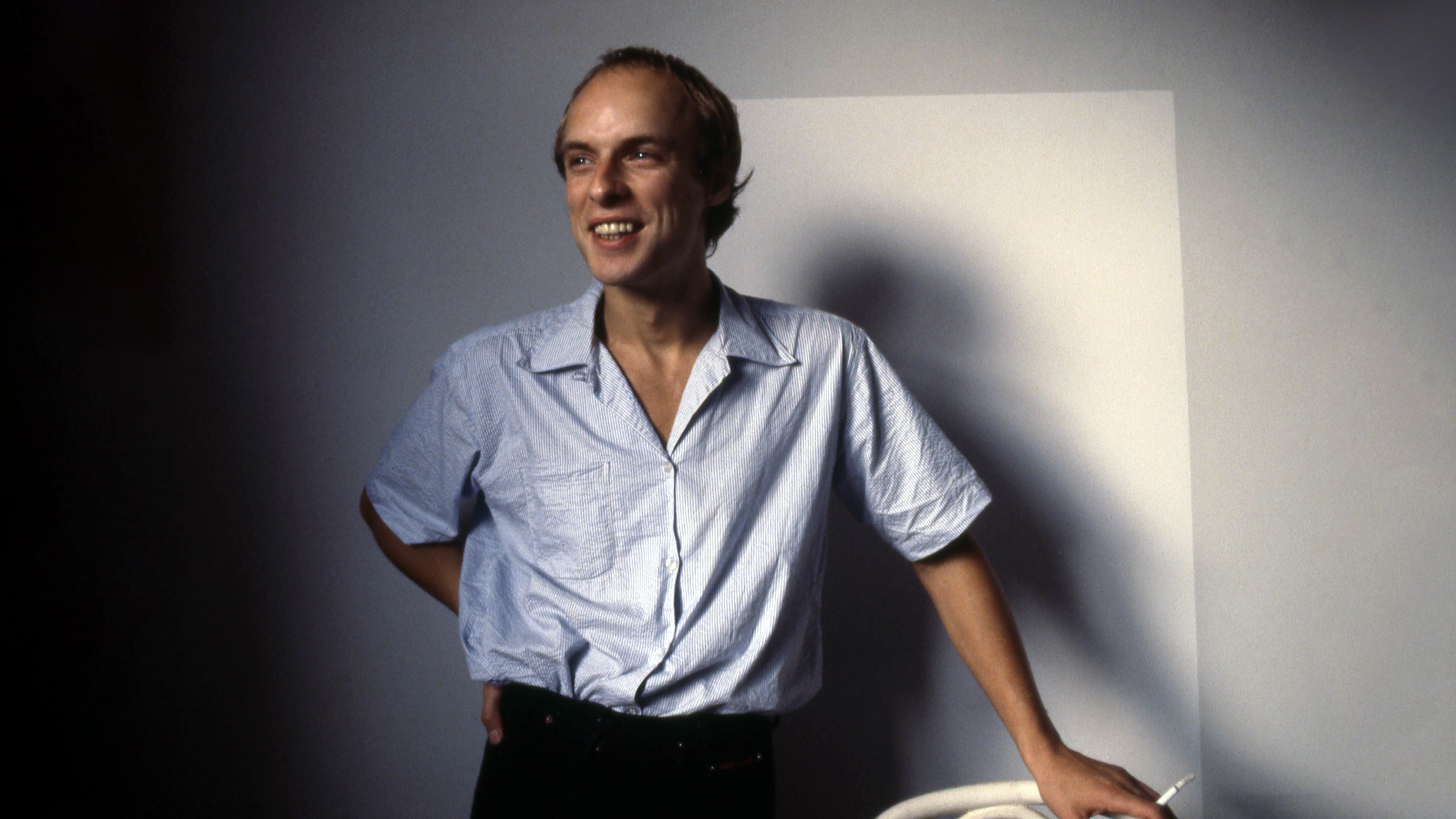

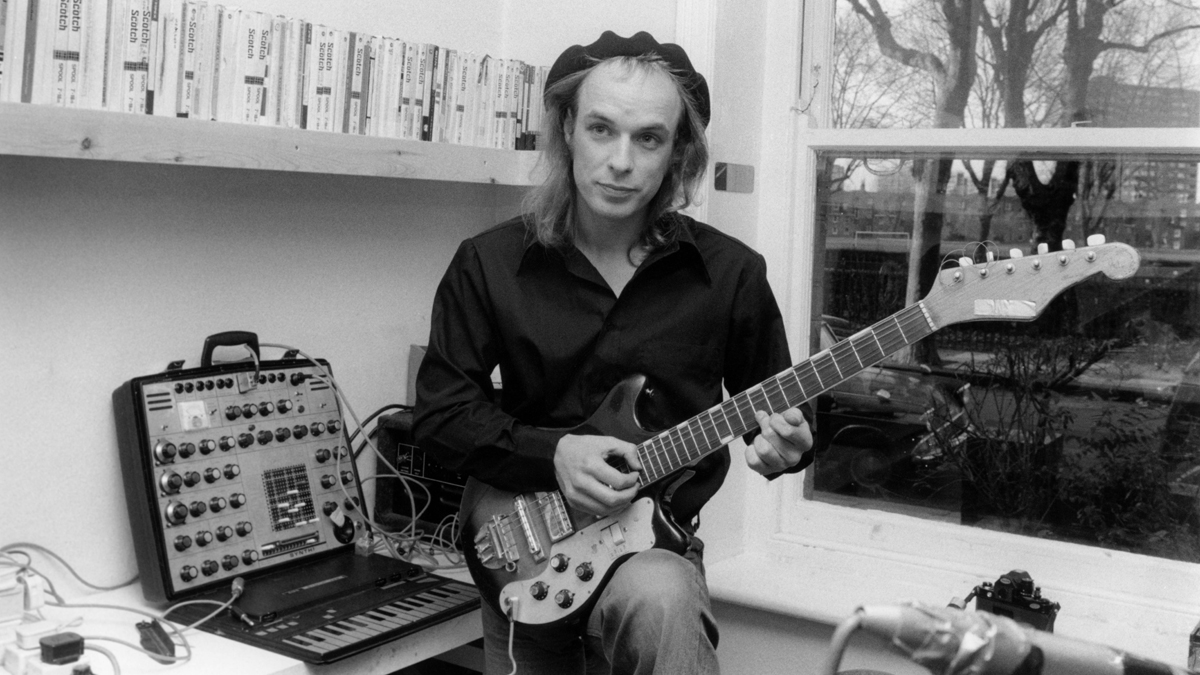

This month, a new documentary about Brian Eno is being released. As befits its subject, Gary Hustwit's Eno challenges its own form: for each screening, the filmmakers algorithmically assemble a different version of the film from a library of clips and components, so no two audiences see the same thing.

Brian Peter George St. John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno is hard to sum up. Even a broad-strokes biographical summary would more than fill the rest of this column. He is a producer, a musician, a conceptual artist, and a kind of general-purpose creative sage.

He has impacted me personally by not only producing my favorite Talking Heads song and the only U2 song that I like, but also by designing the sound I heard every time I turned on my first office computer. In a New Yorker profile, Sasha Frere-Jones says of Eno: “He looked like someone who owns lots of expensive things, which he does, and is used to being listened to, which he is.”

Eno is closely associated with ambient music. He didn’t invent the concept, but he did coin the name. The word comes from the Latin verb ambire, meaning “to go around”. It shares the same root as ambiguous and ambidextrous. In 1978, Eno released the first ambient album to be named as such, Ambient 1: Music for Airports.

This was the first in a series that also includes Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror, Ambient 3: Day of Radiance, and Ambient 4: On Land. These albums are not meant to hold your complete attention. In his book about Music For Airports, John Lysaker describes Music For Airports as “more like a natural space than a painting—phenomena pass by at different speeds and continue after our attention has shifted elsewhere.” He also says that “it is too interesting to be ignored and too diffuse to be followed.” Now that we hear ambient music in every boutique hotel lobby, it doesn’t seem very remarkable, but it was a bold idea in 1978.

MFA is not just noteworthy for its atmospheric, drifting sound, but also for the process that Eno used to create it. The album is comprised of tape loops deliberately played out of sync with each other, so that their contents combine together semi-randomly.

I made many, many pieces of music using more complex variations of the idea that it's possible to think of a system or a set of rules which once set in motion will create music for you

In a 1996 lecture, Eno cites Steve Reich’s groundbreaking tape composition It’s Gonna Rain as a key influence on this idea. “I was so impressed by this as a way of composing that I made many, many pieces of music using more complex variations of that… the idea that it's possible to think of a system or a set of rules which once set in motion will create music for you.” In his generative works, Eno is not a composer or performer, but more like a programmer or editor, designing a mechanical or algorithmic process, and then selecting from its output.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Generative art is another concept that has become unromantic through familiarity, but I think that speaks to a lack of imagination and taste among present-day AI enthusiasts. In a 1978 interview with Glenn O’Brien in Interview Magazine, Eno describes editing a piano note from MFA because it “seemed to appear in the wrong place.” It isn’t enough to have machines make your art for you; to get a good result, you still need to have good editorial judgment.

The background

While waiting for a flight in Cologne Bonn Airport, Eno wondered what kind of music would work well in such a place. He was open to the concept of Muzak, but he disliked how it seemed to be trying to distract or anaesthetize him. He wanted to feel serenity, not numbness, and he also wanted music that would complement the sounds of the airport rather than competing with them.

Eno recorded some of the album in Conny Plank’s studio while he was working with David Bowie on Low. (He presumably finished the rest at home.) Eno also designed the album cover and wrote the liner notes, in which he explained his goals: “Whereas conventional background music is produced by stripping away all sense of doubt and uncertainty (and thus all genuine interest) from the music, Ambient Music retains these qualities… Ambient Music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.” The album’s back cover is a graphical score representing the tape loops’ interactions on each track.

The production

I briefly touch on Eno’s production process below, but for a deeper look, see this explainer on Reverb Machine. I also recommend you try out this interactive guide to generative music created by Tero Pariainen.

Music for Airports is comprised of four tracks, each of which is named with a simple pair of numbers: side one track one, side one track two, side two track one, side two track two.

The theory

1/1

The basis for this track is an improvisation recorded by Robert Wyatt on piano, Eno on electric piano, and a guitarist and a bassist (I can’t figure out who). They were playing in D Mixolydian mode (D major but with C instead of C-sharp), a scale that evokes both medieval Europe and the blues. The piano is a little out of tune, which adds to the wistful atmosphere.

Eno liked how the two pianos sounded together, so he ditched the guitar and bass. He made tapes of each isolated piano track and ran them through an echo unit (probably a Maestro Echoplex). He then took each tape and spliced its ending and beginning together, creating an endless loop.

Eno set up these loops on two tape recorders set to half speed, so the sound would be pitched down an octave. (If you want to hear what the piano sounds like pitched up an octave, listen to “In My Life” by the Beatles.) Finally, he recorded the loops’ playback into yet another tape recorder.

2/1

This track is made from seven tape loops of people singing single notes on “ahhh”. The voices belong to Christa Fast, Christine Gomez, Inge Zeininger, and Eno himself. He added a few loops of synthesizer tones as well.

In the 1996 lecture, Eno explains: “One of the notes repeats every 23 1/2 seconds. It is in fact a long loop running around a series of tubular aluminum chairs in Conny Plank's studio. The next lowest loop repeats every 25 7/8 seconds or something like that. The third one every 29 15/16 seconds or something. What I mean is they all repeat in cycles that are called incommensurable -- they are not likely to come back into sync again.”

The track uses only five different pitches: A-flat, C, D-flat, E-flat, and F. I hear the key as Ab major, F minor, or both. My sense of the key center drifts and floats, depending on which notes are currently playing and which ones have played recently. It’s especially cool when the C and D-flat happen to coincide, because the friction enlivens what would otherwise be a bland consonance.

1/2

This track combines the vocal loops from 2/1 with piano loops. Unlike in 1/1, the piano is not slowed down, so its timbre is (relatively) normal. There’s an arpeggiated chord mixed in among the single notes, the notes F, C and G. You could call it F(add 9) (no 3rd). The chord’s ambiguity makes it fit equally well into Ab major and F minor.

2/2

The final track is a break with the rest of the album’s acoustic(-ish) timbre, comprised of loops of notes that Eno played on an ARP 2600. This synth is known to jazz fusion lovers as the one that Herbie Hancock plays on Chameleon, and is known to Star Wars fans as the basis for R2-D2’s voice. Eno uses a vaguely horn-like setting, and plays a note collection that suggests Bb major (B-flat, C, D, E-flat, F and G). He must have played with the tape speed, too, because the track is tuned several cents flat. (The first track is also little flat, as you discover if you try to play along.)

The reception

MFA got a mixed reception at first. Alan Niester wrote in The Globe and Mail that it “is better suited to an airport on one of Jupiter's moons than one here on the earth. As pure dish-doing, bed-making background grunge, it ranks right up there with Genesis albums and The Sound of the Humpback Whale.” Lydia Lunch said, “It’s like drinking a glass of water. It means nothing, but it’s very smooth going down.” Its reputation has improved, however; Pitchfork gave it a rare 10/10.

MFA has attained enough highbrow cred that some classical ensembles have performed it live. The Bang on a Can All-Stars arranged it for cello, clarinets, samplers, guitar, percussion, piano and bass. (They have even performed their version at a couple of airports.)

Dedalus Ensemble uses a larger ensemble of guitar, piano, flute, clarinet, saxophone, trumpet, trombone, violin, viola, cello, double bass and vibraphone. Psychic Temple’s does a jazz version of 1/1 and the result sounds remarkably like Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way. This comparison would probably make Eno smile, because he loves Miles’ albums from this era.

Given Eno’s love of looped samples, it’s unsurprising that his music gets sampled a lot. June by Copywrite samples 1/2:

Zero 7’s remix of Radiohead’s Climbing Up The Walls also samples 1/2.

MFA has inspired more experimental kinds of music as well. William Basinski’s Music for Abandoned Airports: Tegel is a straightforward homage. The Black Dog’s Music for Real Airports is more of a rebuttal; the band thought that Eno’s music is too serene and optimistic, and doesn’t express the dystopian aspects of air travel.

Does it actually work in airports?

You may be wondering whether MFA was ever tested to see how well it serves its stated function. There have been a few experiments. The album was played in New York’s LaGuardia Airport for a brief period in 1980, and according to Victor Szabo, travelers and staff didn’t like it, saying that it “induced unease” and that it “sounds like funeral music”. In 1984, Berlin’s Tegel Airport tried it out, and employees found it annoying enough to protest the “interference”.

MFA can indeed feel icy and unsettling; remember Alan Niester’s remark about the moons of Jupiter. However, it is nowhere near as icy as some of the music that it inspired. Compared to Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works Volume 2, MFA is like a warm bath.

I love both Eno and Aphex Twin, but I definitely have to be in the right frame of mind. John Lysaker describes MFA as having “an accidental quality, as if one found oneself in a hall, halfway between two open doors, each releasing tones now mixing in the corridor.” I work in a music school, and often find myself having this exact experience while sitting around waiting for my classes to start. It can be a nice effect! But it can also be bothersome, or even stressful.

Lysaker praises MFA for inducing reverie, “a kind of pleasant perplexity—what is this, where is it going, how am I to respond?” Reverie is definitely preferable to numbness, boredom or anxiety. But it only works if you’re hearing the music voluntarily, which usually means hearing it in private, or on headphones.

It’s one thing to have music playing in a bar or coffeeshop, a place where you go to seek out a certain kind of atmosphere. But in the airport, the main thing I want is quiet. With every passing year, it gets harder to find public places without unwanted ambient sound, especially since people started carrying Bluetooth speakers around with them everywhere. Maybe Eno should retitle his album Ambient 1: Music for Airpods.

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.

“It’s radical. It’s like magic. I get chills”: How Rick Rubin’s philosophy of chance led System of a Down to the first metal masterpiece of the 21st century

“I just treated it like I treat my 4-track… It sounds exactly like what I was used to getting with tape”: How Yves Jarvis recorded his whole album in Audacity, the free and open-source audio editor