"There was water dripping onto the gear and we got interrupted by a cave diver": How Mandy, Indiana recorded their debut album in caves, crypts and shopping malls

I’ve Seen a Way reflects on global instability and misogynistic attitudes through a sonic palette of tribal drums, distorted feedback and abstract electronics

RECORDING WEEK 2024: Hailing from Manchester, experimental noise band Mandy, Indiana’s debut album, I’ve Seen a Way, reflects on the chaos of global instability and misogynistic attitudes through a sonic palette of tribal drums, distorted feedback and degenerated electronics.

The four-piece initially came to fruition after vocalist Valentine Caulfield and guitarist/producer Scott Fair appeared on the same live bill with former bands – the duo would later team up and enlist Simon Catling (synths) and Alex Macdougall (drums).

Keen to explore different sound environments in an attempt to capture unpredictable frequencies in their production process, I’ve Seen a Way was recorded in a variety of unlikely off-site locations including a West Country cave, Gothic crypt and a shopping mall in Bristol.

Spliced together by Fair’s edgy production, it’s a raw, propulsive and aggressive debut LP catapulted by Caulfield’s craving to fight societal injustice in her native French tongue.

What can you tell us about how the band formed and the meaning behind the name?

Scott Fair: “We were originally named after a city in America called Gary, Indiana, and thought it was a funny name because Gary is quite a common man’s name and the city’s called Gary. We didn’t really contemplate the wider implications of giving ourselves that name until we signed to Fire Talk Records in the US, who advised us to change it. We brainstormed a bunch of things that had an equally nice cadence to them. From that perspective, we think Mandy, Indiana has a similar bounciness and is even nicer to say!”

Val Caulfield: “Scott and I met in 2016 after being on the same bill with previous bands. He quite liked my band and I quite liked his, so we stayed in touch, and when both projects ended I had an idea for a new one. I also liked the idea of doing something in my native French language. We started making each other playlists and brainstormed until the beginning of 2020 when we started playing with our former drummer and began to think of ourselves as a three-piece. Then we decided to add synths to our live shows to make Mandy, Indiana a foursome.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

SF: “There are a lot electronic influences in the sound, but we wanted it to be more of a band than an electronic project so we could perform as much of what we recorded live without relying on backing tracks. There are some things that are still very hard to recreate on stage that we still have to rely on a sampler for, but for the most part we’re recreating everything with live drums, vocals and guitar.”

Were you influenced by Manchester’s post-punk scene?

SF: “Not so much. There are very strong ties with bands like The Fall and Joy Division, but they were never touchstones. When I moved to Manchester from North Wales those bands were obviously a point of pride for people who came from the area, but I didn’t grow up in that culture. I’ve not lived in Manchester for a while, so the connection is more about where we met than where we’re based, but our other band members, Simon and Alex, are still based in Manchester.”

We understand that visual arts are also an influence. For example, in what way are you inspired by French filmmaker Julia Ducournau who directed provocative films like Raw and Titane?

SF: “I’ve always found myself coming out of a cinema or watching a movie at home and feeling really inspired to write music. Sometimes that’s the score, a song that I’ve heard or the pairing of music and visuals. Julia Ducournau is an influence and Gaspar Noé is someone I mention a lot, particularly films like Climax where the music is thrust into the audience’s face in a very obvious way.

“Beyond that, playing video games and listening to music and watching a lot of YouTube videos – I’m a big fan of the algorithms they use to throw up random content because I seem to be interested in a lot of it. Trying to recreate those feelings is often a leaping off point for me.”

Would you say that the music is designed to shock the listener in some way?

VC: “The music tries to keep people on their toes, but to voluntarily try and shock would seem like quite a pretentious way to work. We’re making music that we find interesting with the understanding that it’s not the most accessible sound. We don’t want to put a persona before the music we’re creating – we’re trying to be very honest in the sense that we’re not exclusively making music for anyone other than ourselves.”

SF: “We don’t have any desire to do something that’s been done before, but Mandy, Indiana is obviously not created in a vacuum. Our natural instinct is to try and create something original, experimental and progressive. Social media is influencing the way the music industry operates and it’s obviously a very different landscape to how it was 10 years ago. If we can build a following then maybe we can do something even more non-traditional to making albums.”

VC: “The day we do something predictable is the day we’re no longer around. We’ve even joked that instead of doing a second album we’ll do something completely leftfield, like write, direct and star in a film.”

Bands often talk about taking a DIY approach to music-making. What does that mean to you?

SF: “The record wasn’t DIY because we had a lot of help making it. Initially, I was planning to produce the whole thing, but it quickly became apparent that because we wanted to record on location and mix styles and genres, that path was a bit too much to manage.

“It was DIY in the sense that we didn’t say, hey, we want to record an album and then someone made it happen for us, we started recording the album while it was being written because we knew that the recording process would be a big part of things and the album continually changed as the ideas came into clear focus.”

VC: “It’s more non-traditional/experimental than DIY. We didn’t make the album in the way that lots of bands do, which is to write and then go into a studio to record. We decided to do a bunch of weird experiments and see how they would work out, and thankfully there were many talented and confident people around who could help us achieve that.”

Is the industrial-sounding energy and aggression of the music a physical response to grievances you have about the world we live in?

VC: “That’s where most of the lyrics are coming from, for sure. The way I wrote for this project was to listen to Scott’s songs on repeat until I could work out how they made me feel and what I want them to be about. In the midst of a bunch of shit happening in France and the UK while I was still living here, I reflected a lot on my condition as a queer woman of colour.

“I looked on what I saw in the world and how I and other people have been treated. There is no real alternative to the horrible, dehumanising mainstream politics and I tend to react to that, but I guess it’s easy for all of us to look at the state of the world and be angry.”

Is the track Drag [Crashed] a response to sexist attitudes you’ve encountered throughout your life?

VC: “It’s not even a response; it literally addresses a list of things that were said to me or about me. The first few lines of the song relate to things that were said about me to my father when I was a toddler. He was told, “Oh, you’re going to need a gun to fend off the boys with that one” or “You’re going to be a young granddad”.

“These are things that are put into young girls’ heads when they grow up, so the song aims to take a look at that while understanding that in 2023 there is no way for a woman to perform an acceptable form of femininity because no matter what you do it will be never be done correctly.”

Have you noticed similar prejudices within the music industry itself or do you have the sense that it’s levelling up?

VC: “It’s a hard one because although I’m a female artist I’m painfully aware that I’m not in an all-female band or trying to make it in the industry by myself. I do see the way that all-female bands are treated, but I also see how some people use that as a gimmick.

“I guess it’s sad that we can’t listen to artists for who they are without them being used to sell tickets or have people tell us who we should listen to because they have something interesting to say. I have friends who work in the industry that are not artists and they tell me it’s depressing to see how women are treated behind the scenes, but it’s kind of the same everywhere.”

Despite the subject matter of some of the songs, your vocal is often quite calm and measured…

VC: “It’s not that measured when I’m performing. I’ve actually been crying quite a lot on stage recently and getting really emotional about certain things. I’ve been called ‘loud’ my entire life and told that how my express myself is aggressive, so I’ve learned to make my point in a more measured way, otherwise I won’t be listened to.”

Do you sing in your native language because you feel more comfortable expressing yourself in that way or because it adds an extra element of differentiation?

VC: “I saw it as an interesting way to approach the music for this band. I grew up in France until I was 19 and all the music I liked was English. When you’re not used to being fed music in your own language, the work you have to do to fully understand and absorb it is different and it was interesting to me to reverse that for an English-speaking audience. Some people are going to like what they hear but when they read the lyrics they might think ‘this person is insane’. That’s cool, but I think you absorb music in a different way when it’s not spoon-fed to you.”

Did the band get together and write the music collectively in a shared space? If not, how did the process unfold between you?

SF: “It’s all done separately. The ideas typically start with me and then I’ll create different demos or versions for tracks where the production ideas are often as involved as the instrumental elements that are brought to me, so there’s an electronic aspect to how I piece things together in a project. Usually the songs are quite fleshed out by the time they get sent to Val and when I get her vocals back it’s just a case of doing my thing.”

Do Simon and Alex have free reign in terms of their contributions?

SF: “The reason that we use live drums rather than electronic drums is because every drummer has a different way of playing. I’ve always struggled to find a drummer I can work well with, but Isaac Jones, Liam Stewart and Alex all contributed to the album and have excellent but very different drumming styles. Once you get to know someone’s style, you can lean into their strengths. For example, Alex is a very fierce and visceral drummer and I’m quite influenced by that.”

Tell us about some of the on-location recording you did for I’ve Seen a Way. For example, we read that some of the vocals were recorded at a shopping mall in Bristol?

VC: “We didn’t go for the process of trying to record at a shopping centre. The first time we played in Bristol we supported a band called Scalping and ended up going for a drink with them and Fever 103°, who were on after us.

“As we were walking back towards the venue we crossed this shopping mall that has very particular acoustics where the sound reverberates in a very weird way. We were all stood around clapping and shouting, so I filmed it and Scott later asked if I could send him that video.”

SF: “A lot of our sounds come from those chance recordings. We rarely take an entire recording rig into a space, but if we are somewhere when something interesting occurs aurally we’ll get the phone out and record. We’re not precious about fidelity or isolation. For example, the place where I live is prone to flooding and you can often hear an old air raid siren going off, so I recorded that onto my phone and thought about sampling it, then decided to recreate it with my guitar.

“So we do incorporate a lot of found sounds or use them for inspiration for the sounds that we make with our instruments. In the case of Val’s vocal in Bristol, I was just listening to the track and heard something in my head that told me to dig it out. I could have recreated the same sense of uneven delay that you hear on the recording, but there’s a lot of background noise in there too and I really like adding all those textures and layers.”

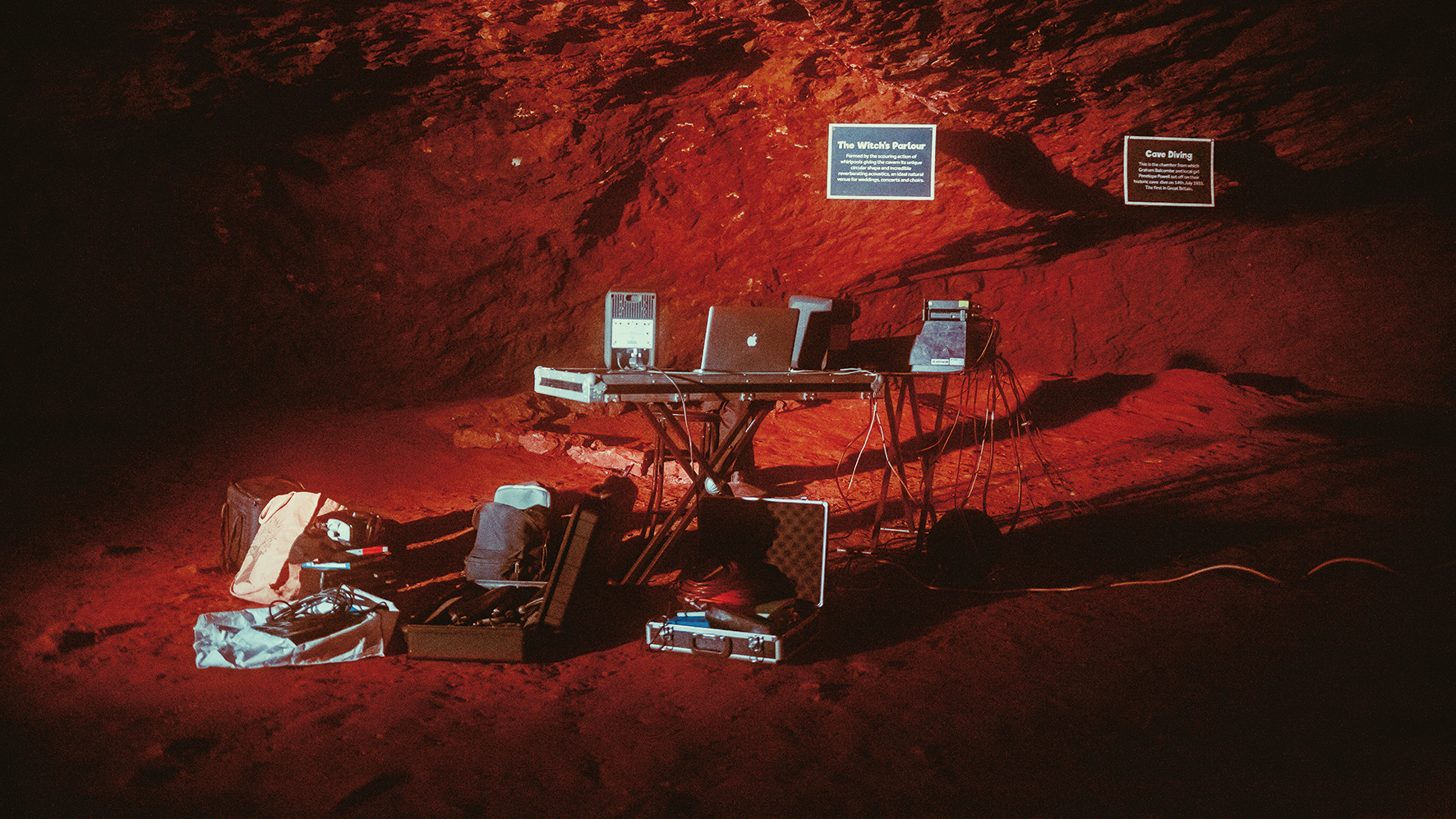

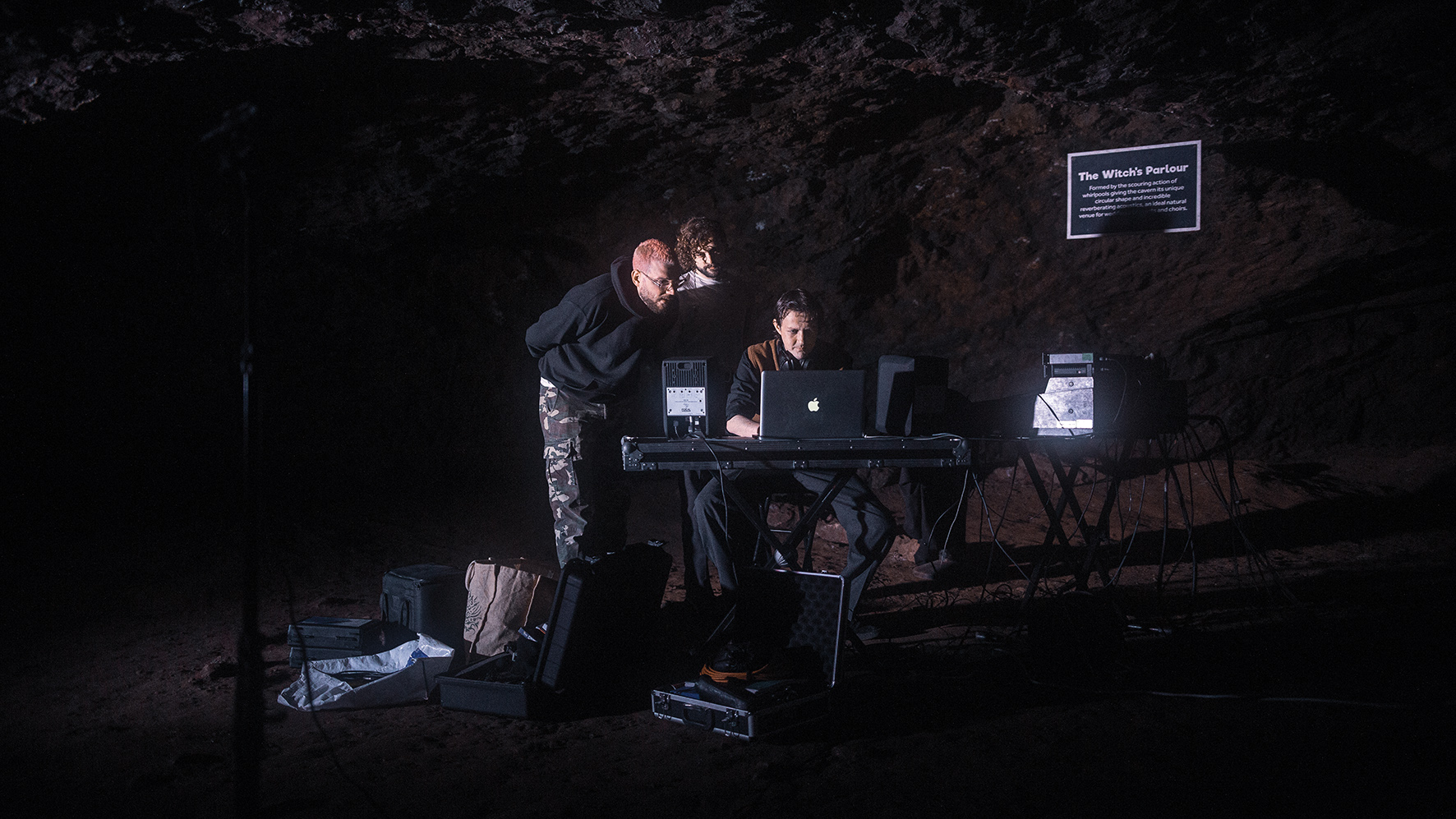

You also recorded at various other locations. For example, some of the drums were recorded at a cave in the West Country…

SF: “We wanted to stay outside of a studio environment as much as possible and find spaces that had a unique character that other bands had not recorded in before. There’s a video game called Dear Esther where the character is exploring caves and that visual stimulation made me wonder what it might sound like if we were in them. We eventually found one not too far away from where our recording engineer and drummer live, so we got on a train and had one of the weirdest experiences of our lives.”

What obstacles did you face recording in the cave and how did you set up?

SF: “We had to walk 20 minutes to get to the location and the mouth of the cave was full of leftover props from a dinosaur theme park. We had a big Tascam desk, a full drum kit and lots of mics, cables and outboard gear but didn’t have a lot of time to record. We also got interrupted by a cave diver; there was water dripping onto the gear and we couldn’t listen back to the tapes or monitor anything because the sound was so loud.

“Eventually, we managed to capture everything that we went there to get, but we had to load out in the dark, stumbling through a corridor where they were maturing cheese, which is the worst smell you can imagine, whilst walking underneath a 50ft King Kong statue. It was a bizarre day, but we got exactly what I was hoping for because the recordings definitely influenced the way the record sounded and fed into our decision-making when it came to the production and mixing stage. It would be good to release an instrumental version of the album with the drums higher in the mix, I’d love people to hear more of what we captured.”

Was your recording session at a gothic crypt equally as problematic?

SF: “That was in a church called The Mount Without in Bristol. Again, it was very interesting acoustically because the crypt has a very low ceiling and much shorter reflections. We didn’t have to worry about cave divers either, although we did record a load of loud speaker feedback and disturbed a meditation and yoga group that was above us in the church.”

The word ‘crypt’ conjures images of coffins littered around…

SF: “I like the idea of what you’re describing and the visual stimulation of being surrounded by coffins, and we did look at places like that, but they were usually next to a busy main road. Unlike the cave, it had to be somewhere that gave us a certain degree of control and was affordable – I don’t know where all the bodies were [smiles].”

Did you perform vocals at either location, Val?

VC: “I was at neither unfortunately, although being incredibly claustrophobic I’m really glad I wasn’t in the cave. The majority of the vocals were recorded in the studio but some bits were recorded in practice rooms. When I write a song there is an amount of trial and error and sometimes Scott chops up my vocals a little bit so they can fit around a track.”

The album is full of distortion. How much of that is computer generated as opposed to running instruments through hardware pedals or outboard?

SF: “There isn’t really any computer-generated distortion other than enhancing things with plugins here and there. I’m slowly beginning to embrace the digital world having always tried to keep everything outside of the computer. I use Logic to make the tracks because it’s easier and we can’t always afford outboard gear.

“Pedals are quite a fashionable thing in the guitar world and I definitely dipped my toe into that by looking at other people’s gear. Earlier this year, we saw that somebody had posted my pedal board on Reddit [laughs], but I try to limit that for practical reasons – it’s already too heavy for traveling abroad.”

Is limiting yourself to a few tools a general rule?

SF: “I like to get the most out of things so I’ve probably only got six or seven pedals, which is quite modest compared to most bands. Boutique pedals are typically very good yet very expensive, but there’s a guy called Orgeldream in Bristol who made me a noise generator pedal with different oscillators at a really reasonable price and I used that for a lot of the noisy rhythmic parts. I also use an Old Blood Noise Endeavors Dark Star pad reverb and a Death by Audio Echo Dream.”

What software plugins are you using?

SF: “CamelCrusher is a bit of a go-to for drums at the moment and is an A-grade distortion plugin. I also saw a video a while ago on YouTube with some guy saying, ‘Here’s ten free plugins that are free but don’t sound like they should be free!’, so I downloaded a bunch of stuff and there’s this thing called Pocket Dimension by Freakshow Industries.

“It uses an Eye of Providence cult symbol for a cursor and in the background there are all these AI-generated landscapes that look very dark and monstrous. You basically put this thing on a channel, drag the cursor around and it fucks with the sound. I love things that are aesthetic-based and can be engaged with on a visual level, so you can almost play the plugin instead of just looking at a bunch of dials and knobs.”

Despite the combination of technologies used, it sounds like Mandy, Indiana is easily transferable to the live stage?

SF: “Because we’re not all in the same location we’re still working out how to integrate some of the album stuff into the live show. On the track Pinking Shears, we use a sample of John Cage talking about Glen Branca where he says, ‘If the circuits don’t work, the music collapses’. We’ve borne that out in reality at a lot of our live shows because if anything electronic breaks down then things do collapse a little bit.

“We don’t have an unlimited supply of gear or money and use what we can beg, borrow or steal, so tracks often get cut short when something breaks or falls out, but I’m kind of okay with that. Personally, I much prefer seeing a live show that has an element of chaos or unpredictability and find it quite endearing when something goes wrong because it breaks down the barrier between the artist and audience.”

VC: “It’s great until you find yourself sat in the middle of the floor surrounded by two thousand incredibly sweaty people waiting for the breakdown in the last song of the set and you can’t hear anything. The last show we played I was literally sat there, couldn’t see the stage and the song stopped [laughs].

“Scott’s right, it does keep things exciting, but it’s also about how people react to us. It can be draining if I feel like I’m not getting anything from the audience in front of me, but when we have a proper connection, it’s amazing.”

Mandy, Indiana's debut album I've Seen A Way is out now on Fire Talk Records.

• Get more recording stories and features at Recording Week 2024 here!

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track