“Whether a listener is using Airpods or in Berghain next to a wall of speakers, the objective is to try to create a mood in people’s minds”: Producer and engineer Matt Karmil on crafting a mix that translates to any environment

Matt Karmil chats to Danny Turner about the tips, tricks and studio techniques behind his sixth LP, No Going Back

Diagnosed with Epstein-Barr virus from an early age and prone to long stretches of fatigue and illness, Matt Karmil’s tender years were spent practising classical guitar and honing his fascination for electronic sound, initially experimenting with an Amiga 500 computer and a 4-track recorder.

Having made hundreds of tracks without any intention to release them, time spent in Cologne and an introduction to the Kompakt label convinced Karmil to dip his toe into the water and release his debut tech house LP, ---- (2014).

In the following years, Karmil relocated to Paris, Berlin and a quiet forest in Sweden, releasing select EPs and albums reflecting his love for loops, samples and textures. He also began engineering for a diverse range of artists including DJ Koze, Bicep and Neneh Cherry.

Following a pandemic-induced hiatus and encouragement from Underworld’s Rick Smith, Karmil finally found confidence to release his sixth album, No Going Back. Comprising of melodic, ambient micro-house, the LP veers towards the producer’s newfound appreciation for emotional, minimalist atmospheres and sound spatialisation.

For many musicians, creativity is an expression of their surroundings. With that in mind, how has living in so many different European locations imprinted your work?

"I grew up in Salisbury, but right now I’m in Oslo, which is a very different environment to that near Stonehenge, but a lot of my albums, including the latest one, are quite retrospective. I’ve made hundreds of tracks during various periods of my life, so when it comes to making an album I tend to just dip into the archives and find pieces that fit together alongside brand new pieces. Those ‘frozen’ moments are definitely super-influenced by location.

"I’ve lived in Stockholm for quite some time, Berlin and Cologne for many years and they’ve all been informative to my sound, but Cologne probably had the biggest influence on my understanding of house music. It’s the quintessential European city, but meeting people aligned with the Kompakt label and doing a lot of DJing in clubs and outdoor venues was a real eye opener."

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

As a child you were forced to spend a lot of time indoors. Did that provide the impetus for your musical education?

"I had Epstein-Barr virus, which is very similar to long Covid. If I got a cold or flu it would last 6 or 7 months instead of a few weeks and that plagued me from between the ages of 9 and 24 years old. Having an emotionally and physically debilitating illness was quite fundamental to my primary experiences of life and the guitar was quite literally an escape from that, but I stopped playing in my 20s because I really wanted to break away from that painful connection.

"With the birth of the internet and computers becoming more powerful, I found a guitar teacher who turned me on to music concrète through a show called Mixing It on Radio 3. They’d often play Stockhausen next to Squarepusher, which is when I started to understand the link between avant-garde classical and the birth of labels like Warp Records."

Did you recognise how guitar textures, drones and amplification techniques could be related to certain aspects of electronic synthesis?

"I played acoustic guitar but very quickly wanted an electric one because I liked rock music, so I managed to borrow a Yamaha four-track when I was 13 or 14 and that immediately turned me on to things like distortion and sound artefacts when playing stuff at half or double speed. As soon as I’d get a feedback loop or delay going I’d love it and that hooked me.

"When I was really young, I remember hearing the album Reggatta de Blanc by The Police. First, I was amazed that when the speakers weren’t on you could still hear the sound of the record playing from the stylus being on the vinyl, but I also recognised that something was up with the delays on the hi-hats. I was also super-obsessed with the feedback on some of the Jimi Hendrix records and how he was pushing feedback groan and tone in the most rudimentary ways."

One of your first entries into gear was an Amiga 500 home computer. Like most people, did you originally buy it to play games on?

"It was a games thing and Batman was the game that came with it alongside the Prince-era soundtrack. There was no internet, so you’d have all this pirated shareware and I remember having to quickly flick the Amiga’s power switch so I could rescue the sound of a kick drum or vocal from its disk memory. I’m not going to pretend that I knew what I was doing when I was 9, but I probably spent longer doing that than playing any games."

You didn’t start releasing music until 2012 when you were based in Cologne. In what way was that decision related to your association with the Kompakt label?

"I’d been working professionally in music up until then and made tons of music when I was a teenager, but releasing it or starting my own label didn’t connect with me. I moved to Cologne to work on a pop music thing with a German reggae artist and a lot of his crew were really tight with Kompakt - then I met Michael Mayer. When I released my first record everyone started playing it which was quite an eye opener. It was a beautiful, affirming thing to be welcomed into a scene by people who just liked the music."

At what point did you begin working as a sound engineer?

"I’d worked in pop music throughout my 20s, either playing guitar on a track, producing or making beats and I lucked out with the calibre of people I was surrounded with. Working alongside mix engineers like Tom Elmhirst was an incredible learning experience and I managed to record with some pretty well-known singers and started producing records to some extent.

"At one point, Kornél Kovács asked me if I could help him finish some music and we hit it off immediately. He was using Ableton and a few machines but understood that I knew a lot about tape machines and how to operate a desk, which led from one thing to another."

Working as a sound engineer must have a circular effect in terms of not only bringing what you can offer but learning from the people you’re working with. To what extent was that applicable to your latest LP, No Going Back?

"The biggest influence on this record was Rick Smith from Underworld. Getting to know him and have him respond to my music just blew my mind. He was so complimentary, enthusiastic, kind and generous and I could genuinely see that the new material resonated with him. The pandemic hit at a very particular time in my life – I literally released the last record on the worst possible day. Suddenly, there were no more shows, which took the wind out of my sails, but Rick gave me the confidence or belief that I had something that was okay to put out again."

In the context of your back catalogue No Going Back seems to have a slightly more smudged, ambient texture to it?

"As I mentioned, there’s a certain aspect where I’m massaging stuff together and trying to make the record a listening experience rather than just making tracks. That smudged effect, homogeneity or blurriness you speak of is probably based on how I felt about the world. The big shock of 2020 made me, and a lot of people in this industry, realise how quickly your normal life can stop completely. Although it feels like things are fine again, I think it left a big scar that’s definitely had an influence on me."

As the LP appears to sound more tonal, does that mean you’ve relied less on your love of sampling?

"I’m blessed to have every sampler I ever wanted, apart from a Fairlight, so I can really delve into that stuff, but I have got more into granular synthesis recently, which might explain that feeling of wanting to smudge the sound. Basically, the album’s as sample-heavy as ever but those samples are more eroded and crushed, while hopefully sounding more refined.

"It’s my sixth album and I obviously don’t want to repeat myself, but there’s a difficult balance between not wanting to release the same record again and again and improving on the things that resonate with me and how I present them to the world."

A track like The Last Time is very atmospheric and you can distinctly hear field recordings of traffic. Is that about capturing a moment in time?

"It’s hard to explain, but there are times in life where something happens that can elicit a very strong feeling and that frozen feeling has been something that I’ve longed to push into the music. It actually has real parallels to granular recording where you can take the smallest aspect of a sound, let it hang and almost freeze or suspend time. The sound of The Last Time is probably somewhere between wanting to understand an emotion by exposing myself to it, taking a look at it and then playing with it a bit before moving on."

A lot of minimalist techno or house music shuns melody because it doesn’t want to appear too commercial, whereas you seem to very much embrace melody…

"When I played the record to a couple of friends of mine they said it was very positive, which was something that was perhaps missing from some of my earlier, more oblique releases. I hope the melodic aspect is subtle rather than jingly jangly, but it’s probably related to me having the confidence to push at the edges of what resonates with me.

"I don’t know if you’d call the album house or ambient – a lot of it doesn’t have drums so there’s definitely something missing in relation to dance music, but I feel that the weight of the melody and sounds marry into some form of alternate power."

As a sound engineer, will you tend to you use all of the same production, mixing and mastering tools for your solo projects?

"In terms of mixing for other people, I’ve basically become very agnostic towards certain technologies. I prefer to work from people’s sessions than stems, so I’ve basically learned how to use every DAW, print my own stems and bring them into Pro Tools. My hardware studio is in the Cotswolds but I can pretty much mix anywhere on headphones and the quality of plugins now has been a game changer. I love working on an analogue desk, but that doesn’t always fit a lot of artists’ sound aesthetic, so it’s rare they I need to run projects on a big console these days."

So this album was mostly created your preferred way, using analogue gear in your home studio?

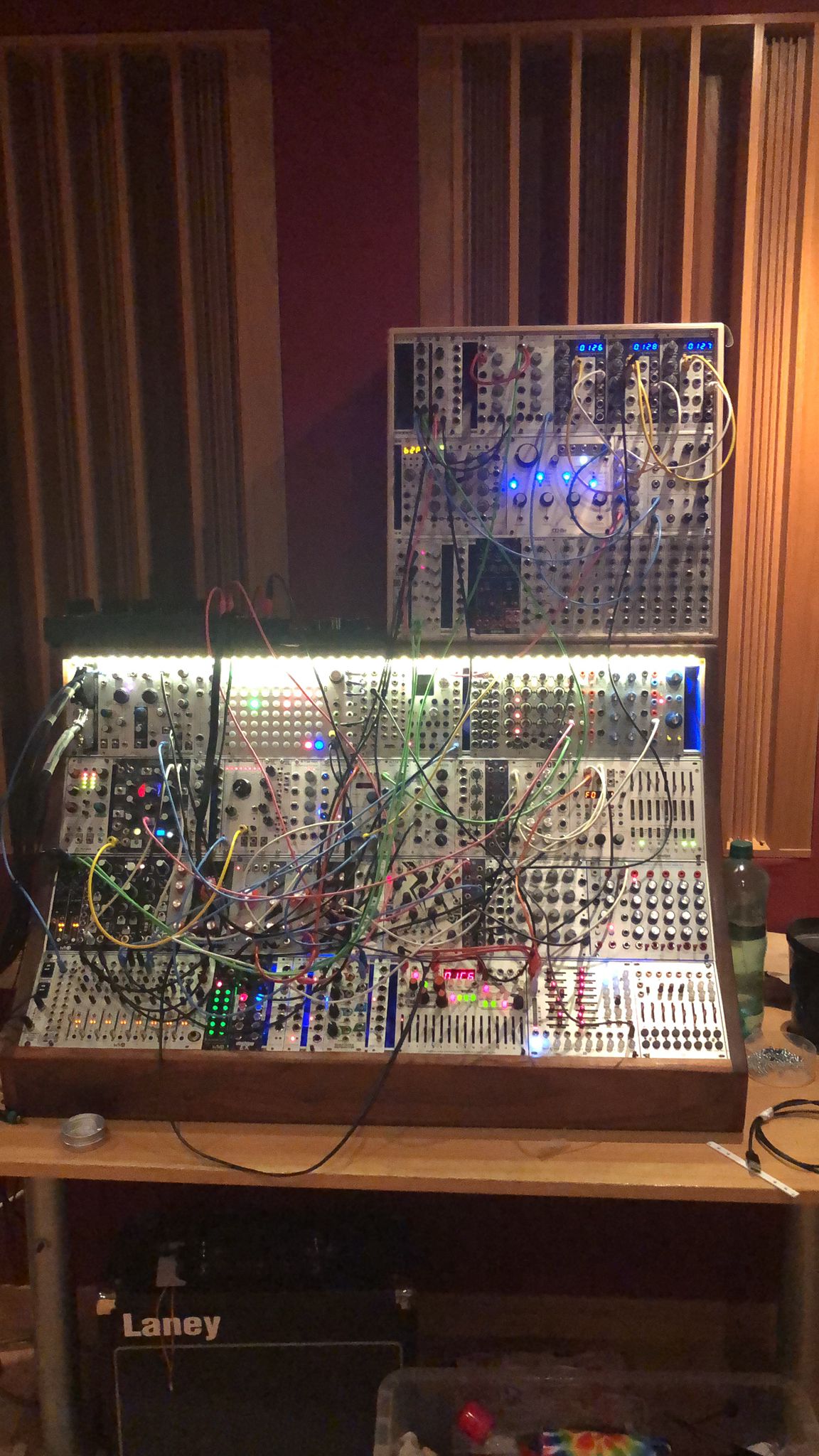

"For my sins, I have a fairly big modular synth setup and lots of very old samplers. For No Going Back, I used tons of hardware from the old Akai S612s to all sorts of vintage bits and pieces, literally capturing every individual aspect in different combinations or groups of direct outs on my Pro Tools system. I’m not using too many plugins – the album’s been made with a lot of blood, sweat and tears."

Have you created your own Eurorack system?

"Yes, and it’s quite large now and hard to take places. I had the idea of buying a huge case and getting rid of the modules, but of course I didn’t [laughs] so now it’s embarrassingly large and ridiculously luxurious, but that’s also tipped the balance creatively because I can patch infinite sounds.

"I quite like The Grid in Bitwig, which is a software version of a hardware modular setup, but then you have modules like Make Noise’s Morphagene and you can’t find a plugin that does that. It’s super-creative and has just the right combination of complexity and simplicity, so there’s load of Morphagene on the album."

Are you looking to find the sound in your head or stumble across ideas through experimentation?

"Using the modular is a skill in itself. A few years ago, I wasn’t quite getting the sound I wanted and I do find myself daydreaming about what I want to do and not being able to do it, but I’ve got a lot better at that.

"Because I’ve done so much work mixing other people’s records, it’s fantastic not to have to sit all day in front of a computer for my own music, so I just try to play with things and save little collections of samples from all of my hardware."

You’ve mentioned being happy to repurpose sounds you’ve made years ago. Presumably that’s easier now as, in the right hands, an album made 15 years ago can sound just as modern as one made in 2024?

"When the Yamaha DX7 was released people probably thought, ah, it’s amazing, but after a few years they didn’t want to hear the DX7 anymore. Everything has its place now and gear’s been re-contextualised, so when I go through my unreleased catalogue I don’t tend to find parts and think, oh god, what was I thinking?

"I may be romanticising things, but I’d also imagine that in the ‘70s people would play guitar for the sake of playing guitar and not with the idea of making or releasing anything. Today, there’s a bit of that with Eurorack – you don’t have to have a goal in mind; you can just enjoy the process or spend time trying to create the sound that’s in your head."

Tapping into your expertise as a mix engineer, lots of artists tell us that they find mixing a chore. Would you recommend people focus on the mix as they’re progressing rather than at a later stage?

"I’d say that whenever you get the feeling that something you’ve made is banging, bounce it, save it and keep on going, otherwise you can often destroy or damage what you’ve done. When you listen to classic records, there’s often something wrong or imperfect about them, so it’s good to throw caution to the wind and be creative because when you’re having a good time you’ll usually find a moment that’s worth capturing and then you’re onto something. "

When should you pay optimal attention to the technical aspect of recording sounds?

"I’ve spent a lot of my life trying to be aware of the technical aspect and finding the optimum line between something sounding edgy, exciting and happening rather thinking about whether or not it will sound terrible on a certain format. That’s where the expertise comes in because if you let the tail wag the dog you can destroy the vibe.

"Whether a listener is using Airpods or is in the middle of Berghain next to a wall of speakers, the objective is to try to create an illusion or a mood in people’s minds, and it’s miraculous to me that you can balance those two environments to make something that works well on both. Making something sound as a good as it can in the most possible places and still having the idea translate is the purest part of what mixing and mastering is all about, and you have to be very delicate with the material because you don’t want to erode it or make it worse to fit into those environments."

If you want to be serious about production, is it vital to have an understanding of room treatment before you even attempt to start making music?

"I’d always recommend people spend the money on acoustics before pretty much anything else, because the joy of having a truly perfect room is fundamental, but that’s a whole topic in itself and if you want to do it properly you’ll have to own the property because it’s not worth the expense if you’re going to have to move again. When I was 14 or 15, I can literally remember not knowing anything about acoustics when I was experimenting in the corner of my parents’ room.

"Now, I’m lucky enough to have a full-on, professional, no-expense room that’s incredible, but it’s insane how a bass sound can swing by a null of 20 or 30 dB depending on the space. Thankfully, because headphones are quite ubiquitous these days, I think that limits the huge mistakes you could make and it’s easy to bounce stuff and take a copy of it out to the car. Today, it’s probably less easy to deceive yourself than it might have been for someone in the ‘80s stuck working in a low-budget studio, and I’ve seen some good results with room correction technology too."

Do mastering engineers master their own albums or is it important to get a second ear no matter your expertise?

"I did use a few mastering engineers for my albums on Smalltown Supersound and I really appreciated their work so I’m happy to hand stuff off to them. For this record, I did most of it myself but absolutely appreciated having someone’s final touch to put my mind at ease.

"Thankfully, I’m in the luxurious position of only needing to make a few very small changes, although I guess we’ll find out when it’s released if everyone says it sounds terrible! With the commercial mixes that I do for other people, I’m not expecting there to be a radical difference when they come back from mastering either – if it’s radically different, then my balance must have been a little bit off."

We noticed that there is a Dolby Atmos version of the LP. Presumably that means your studio has a speaker system set up for Atmos?

"It does, yes. I mix in Atmos for loads of people now and that’s been quite a learning curve in itself. I’m lucky enough to sit in a room surround by ATCs, which deliver an incredible sound. The roll out of Atmos for most people is binaural, through Apple Music or Tidal if they’re really invested in it. It’s a very complicated process, but I like the format and it’s been really rewarding to be able to make Atmos mixes for clients that they’re really happy with.

"Having said that, the amount of things that the technology can affect in terms of how things sound in different environments is enormous and you need to find a good midway between doing tricks and explaining to someone that just because you can do something it doesn’t mean that you should. Ultimately, it’s about making something that works within an artist’s aesthetic."

Did you make the album on a standard speaker system setup and then revert to using Dolby Atmos for a separate mix?

"I made the stereo mixes first. In future, I might start a project on Dolby Atmos, but the problem is that if you have a sound in the back left of your speaker, when it does gets folded down to stereo things can start to sound quite busy. With Atmos, you can make an incredible-sounding installation piece or something that will work in a surround format, but you really have to pay attention to how it’s going to sound in fold down quite early otherwise you can quickly find that you haven’t made a particularly great-sounding stereo mix."

While the technology is unlikely to ever become uniform, where do you think Atmos currently sits within the consumer range of multimedia playback?

"Spotify doesn’t have Atmos, which is obviously a big thing, but from what I’ve heard they’re going to roll it out and if they did that would make it ubiquitous because so many people listen to Spotify compared to other streaming services. On Apple Music, I believe the Atmos default is now on if you’re wearing the right Apple headphones and using an iPhone with Apple Music, so people are probably listening to an Atmos binaural mix without realising it."

Should all artists think about adopting it?

"It’s quite important for artists to pay attention to Atmos and try to get it right even if they’re not super into it. The idea that you can deliver one format that can work in a cinema all the way down to binaural or even a mono mixdown in terms of some of the speaker devices that are able to take an Atmos stream is really interesting. One of the benefits is that you don’t then have to go through another approval process to get that mix used for something else or have to revisit the stems a few years down the line. I also think Atmos will become increasingly important as spatial and wearable computers and headsets start to become more in vogue."

Matt Karmil’s latest album, No Going Back, is out now on Studio Barnhus.