“It could just take over and we don’t want that to happen”: It's Macca Vs The Machines as Paul McCartney wades in on AI’s threat to music makers

Despite embracing AI for their last release, it seems the ex-Beatles bassist has since had a change of tune

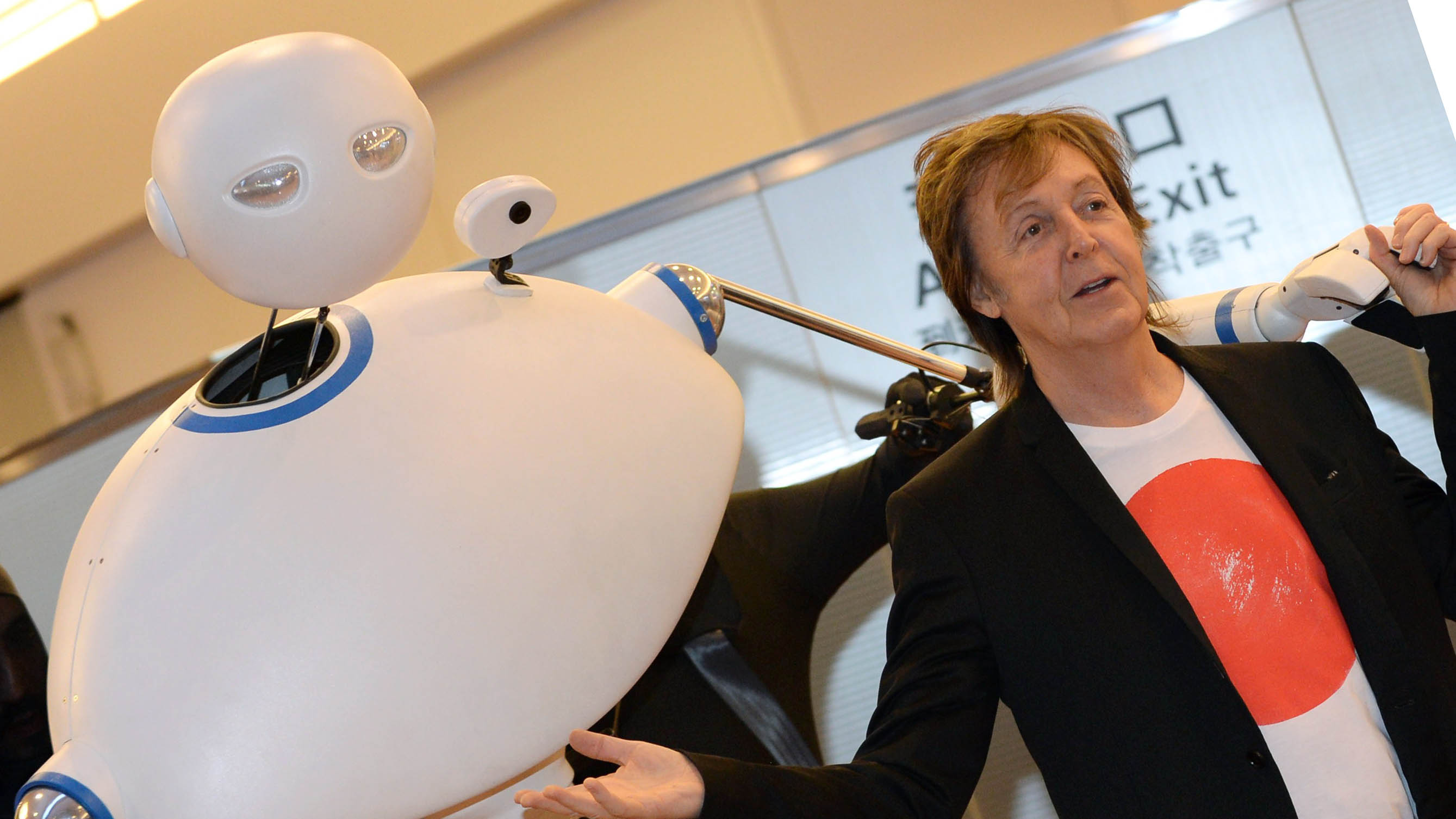

Prime Beatle Paul McCartney has spoken out against the slowly creeping advance of AI in music and his fears that – if left unchecked by new legislation – it’s going to take over.

McCartney’s comments come amidst rising concern about the use of existing content to train AI models. Doing so is not only a questionable use of intellectual property owned by its creators, but something which also ultimately – by facilitating copies and clones to be automatically created – makes the process of humans making music (or writing words or making pictures) a pointless waste of time.

And while notable hold-outs include The New York Times, who have already taken legal action against AI heavyweights such as Open AI – the creators of Chat GPT – and Microsoft, their deep-pocketed backers, other vast repositories of human knowledge and creativity, such as Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation have already signed away the rights to use all their content to power up Open AI’s fake brains.

McCartney is backing the campaign to ensure that artists get paid a fair amount for use of their work.

Be under no illusion, there’s a war taking place with the ultimate prize being music itself, and who will own and create it all going forwards.

All eyes on the prize

AI-powered music generation platforms Suno and Udio are already under fire from the RIAA, which has filed lawsuits against both, alleging "copyright infringement on an almost unimaginable scale".

Meanwhile, a group of 13,500 signatories that includes Thom Yorke and Björn Ulvaeus issued a joint statement demanding that AI companies cease training their models on copyrighted work.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In his statement, Macca said: “We[’ve] got to be careful about it because it could just take over and we don’t want that to happen particularly for the young composers and writers [for] who, it may be the only way they[’re] gonna make a career. If AI wipes that out, that would be a very sad thing indeed.”

That may sound like a contradiction given that Macca and team used AI to separate the vocal stems for last year’s Now and Then, but McCartney is clearly going after the practice of using AI to create original music, rather than audio processing or trickery.

Now and Then was rebuilt with audio software called Mal, which was able to lift John Lennon’s vocal cleanly from a piano part in order to be used alongside new performances from living Beatles McCartney and Ringo Star, alongside existing guitar parts on the demo, recorded by the departed George Harrison.

We therefore sit on the edge of a precipice. If music publishers and record companies allow ‘big AI’ to have all-it-can-eat from their copyrighted work (and if there’s any money coming their way in return, the chances are that they will) then we could be just months away from the AI’s owners (and doubtless the tens of thousands of fee-paying users they want on board) from spamming every media channel you can imagine with the catchiest most ear-wormy hits (in every musical genre) than you can ever imagine. All without any existing A&R, musician, engineer or producer lifting a finger.

There is, of course, the more pragmatic, pro-AI point of view, that this is all just ‘enabling’ and if the result is more brilliant new music out there, perhaps tailor-made to your exact musical taste and being made available at lower and lower costs, then what’s the harm? Who cares if it’s made by a robot or a Robert?

Indeed artist/producer Timbaland is already embracing AI platforms such as Suno to improve his music, giving raw ideas new shape and harmony that he otherwise wouldn’t have come up with. Although Timbaland insists: “You still need that human element to operate this tool,” he says. “It doesn’t replace anything. All it does is add to your arsenal.”

It’s a battle that’s only going to get hotter, with an endgame that, potentially, could end the recording, publishing, music-making and music gear industries entirely. (Keep it light - Ed)

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.

“If they were ever going to do the story of Nero, probably the most decadent of all the emperors, they would have to use Roy Thomas Baker”: Tributes to the legendary producer of Queen, Alice Cooper, Journey and more, who has died aged 78

“A fabulous trip through all eight songs by 24 wonderful artists and remixers... way beyond anything I could have hoped for”: Robert Smith announces new Cure remix album