“He noticed that the studio had a marimba sitting in the corner, and the rest is history”: A music professor breaks down the theory behind ABBA's Mamma Mia

On Mamma Mia's 50th birthday, our resident music prof puts ABBA's infectiously catchy karaoke staple under the musical microscope

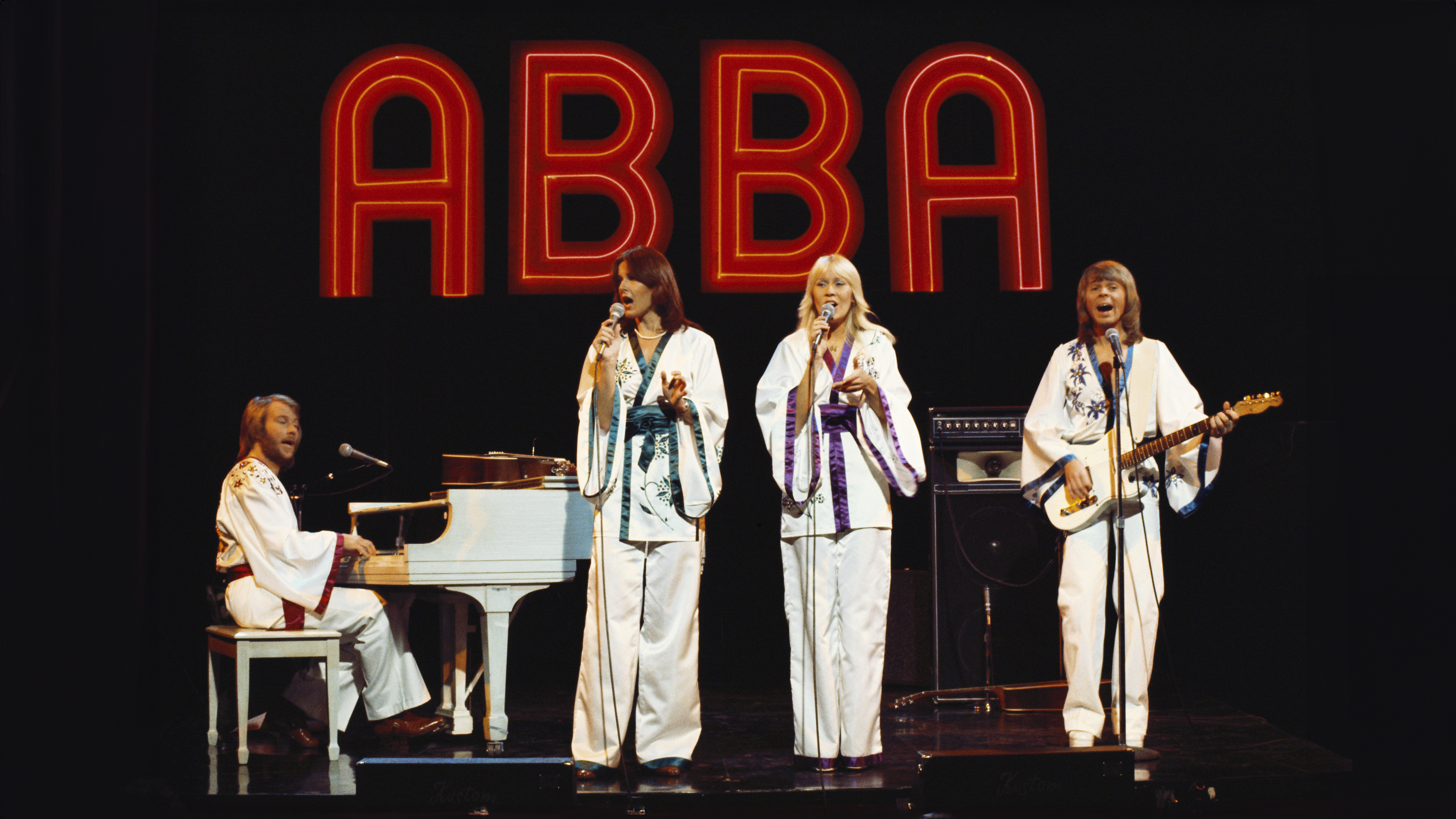

The song that launched a jukebox musical, a pair of smash hit films, and a million karaoke performances, ABBA’s Mamma Mia was recorded 50 years ago this week. Let’s enjoy the endearingly awkward yet peppy music video.

Between Max Martin songs on the pop charts and Ludwig Göransson scores in film and TV, Americans have come to take for granted that Swedish musicians dominate our culture, as the Swedish Institute brags on their web site.

But this is a strange situation when you stop to think about it. Why should a Scandinavian country with the same population as Ohio have such a massive cultural footprint here? It’s not like the charts are full of Finns or Norwegians. There may not be any logical explanation, but for whatever reason, ABBA kicked off the trend.

The background

ABBA members Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus wrote Mamma Mia after their manager Stig Anderson gave them the title as a prompt. (Swedish speakers use the expression in the same way that English speakers do.)

It was the final track written for their third album, also called ABBA, and its runaway commercial success was a surprise. The band had released five other songs from the album as singles, and only added Mamma Mia to the list after it became a hit in Australia.

I learned from Songfacts that ABBA had not put much thought into their English lyrics early on. Before that third album, Bjorn Ulvaeus had seen lyrics as nothing more than a “necessary evil”, a kind of decorative embellishment for the tunes. But as his English improved, his confidence and attention to craft as a lyricist grew as well.

The band recorded the backing tracks at Metronome Studio in Stockholm, with Björn and Benny producing and playing guitar and piano, respectively. The track also features guitarist Finn Sjöberg, bassist Mike Watson, and drummer Roger Palm. Agnetha Fältskog and Anni-Frid Lyngstad overdubbed their paired lead vocals, and then strings, oboe, and additional guitar by Janne Schaffer were layered in.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

He noticed that the studio had a marimba sitting in a corner, and the rest is history

After all that, Benny still thought the track was sounding a little plain. He noticed that the studio had a marimba sitting in a corner, and the rest is history. I mainly associate marimba with cartoon soundtracks and elementary school classrooms. It does appear in a few other iconic rock and pop songs, though, including It’s The Same Old Song by the Four Tops and Under My Thumb by the Rolling Stones. With the advent of digital synthesizers, fake marimba has become more widespread in the mainstream, starting with Africa by Toto.

Most current pop songs are based on short, repetitive chord loops, and they generate musical interest though changes in soundscape. Mamma Mia works differently: the instrumentation and timbres stay pretty much the same throughout the song, but there are lots of different harmonic and melodic ideas.

Nostalgists like Rick Beato complain that pop has become simpler and less interesting than it was in ABBA’s time, and that’s true as far as notes on the page go. But production and arrangement have evolved a lot since then, which is why Mamma Mia sounds both so sophisticated and simplistic at the same time.

The theory

Mamma Mia begins with a distinctive hook. Over a D pedal in the bass, the guitar, piano and marimba quickly alternate D and A, a power chord that is neither major nor minor. Next, you hear alternating D and A-sharp/B-flat. This is very strange! Does it imply a D augmented chord, or maybe a Bb chord with D in the bass? We don’t know yet. I’ll be calling it D augmented (D+) for now.

The other odd feature of the intro is its rhythm. The pattern changes from D to D+ half a beat before you are expecting it to, wrong-footing you rhythmically. It’s a weird and mildly annoying idea, but it certainly gets your attention. As we learned in a previous column, all truly epochal pop smashes have to be at least a little annoying.

When the song proper begins, the key reveals itself to be an unambiguously sunny D major. The first half of the verse (“I’ve been cheated by you”) goes like so:

| D A/D | D | G | G |

| D A/D | D | G | G |

You could think of that A/D chord as Dmaj9 with no 3rd, or as a functional combination of A and D chords.

The second half of the verse (“Look at me now”) is another eight bar phrase:

| D | D+ | D | D+ |

| G | G | A | A G D|

The second D+ chord acts like an augmented V chord in G major. Those last two G and D chords comprise an emphatic riff that anticipates the prechorus (“Just one look and I can hear a bell ring”). This section is short, just four bars.

| A | A G D | A | A |

The chorus is three distinct mini-sections strung together. I’ll call them Chorus A, Chorus B and Chorus C. Here’s Chorus A (“Mamma mia, here I go again”):

| D | D | G C G | G D/G |

| D | D | G C G | G D/G |

You could hear D/G as Gmaj9 with no 3rd. ABBA evidently loves that sound. The C chord is a mild twist; it’s from outside the key of D major, briefly implying D Mixolydian mode instead.

Chorus B (“Yes, I’ve been broken-hearted”) is only six bars long:

| D | A/C# | Bm | F#m/A |

| G C G | Em A |

This section starts with a nice descending major scale bassline that gives it a classical feel. You would expect it to move from Bm to D/A, but instead it lands on a much more wistful F#m/A, the infrequently-used mediant chord.

Finally, Chorus C (“Mamma mia, now I really know”) recapitulates parts of Chorus B:

| D | Bm | G C G | Em A |

The second verse and prechorus are the same as the first. The final chorus does the A and B parts, followed by two more A parts and another B part before finally coming to the C part. The song ends with the intro riff.

The reception

ABBA is as widely loved as any pop group ever has been, but they are also the focus of intense animosity. Their songs are full of unshakable earworms, which can be maddening if you are not a fan. But even if you are a fan, you are likely to consider them to be a guilty pleasure.

Music theory teachers love ABBA songs because they use lots of clear and conventional Western tonal theory

While ABBA’s music outwardly resembles American rock, it bears no trace whatsoever of the blues, which is the basis for rock’s claims to artistic credibility. Music theory teachers love ABBA songs because they use lots of clear and conventional Western tonal theory, making them easier teaching examples than songs by Aretha Franklin or James Brown. But this is exactly why people like me prefer Aretha Franklin and James Brown.

The best thing about ABBA songs is their friendliness to audience participation. The melodies occupy narrow pitch ranges, and they don’t use big interval jumps or chromaticism. Agnetha and Frida are terrific singers, but you don’t have to sing well at all to get an ABBA song across at karaoke night; all you need is enthusiasm.

Just because ABBA songs are easy to understand and sing along with, does that make them insubstantial?

Just because ABBA songs are easy to understand and sing along with, does that make them insubstantial? Daniel Ross gives Mamma Mia rapturous praise on Classic FM. He calls it “a work of decadent pop experimentation and an absolute treasure trove for music geeks” and compares its ornamental trills to Mozart. He admires the unconventional use of marimba and oboe, and he marvels at the fact that the chorus is the quietest and sparsest part of the song. That is high praise from a highbrow source.

I don’t dispute ABBA’s craft, but is craft the same as art? As I listen to Mamma Mia, my inner rockist struggles with my inner poptimist. Is pop supposed to be edgy or subversive? No one is less subversive than ABBA. Or is pop supposed to be fun and inclusive? No one is more inclusive than ABBA. So it really depends what you consider the job of pop music to be.

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.