How a lone Bee Gee became the first person to use a drum machine on a pop hit

When it hit the chart in 1969, it was the first exposure the record buying public had to an electronic beat

Music's many stylistic evolutions have always been underpinned by technological innovation. Think of how many genres and attitudes are formed around a specific set of instruments - or a prerequisite gear toolkit. Electronic music might have spawned countless sub-genres, but they all still orbit one firm foundational element - the drum machine.

But, as with our recent look at the first band to use a synth on-record (astoundingly, The Monkees!) the tech that would shape so much of the future can be, at first, seen as a colourful novelty to wackily incorporate into an existing production framework.

In terms of the drum machine, its origin in terms of popular music stemmed less from being perceived as a disposable new toy, and more out of the necessity for artists to work and write music quickly without the need to work with (or spend money on hiring) a real drummer.

Fascinatingly, machines designed to simulate rhythm date as far back as 1930 (and Leon Theremin’s ‘Rhythmicon’). These early contraptions later evolved into electric keyboard-accompanying rhythm boxes, such as Wurlitzer's Side Man. Though precursors to what we'd come to know as a drum machine, their controls were limited, and their sounds basic.

But, it wasn’t until the late 1960s that standalone electronic drum machines begun to be commercially available. Spearheaded by the Japanese companies Korg (then known as Keio-Giken) and Ace Tone - a company founded by future Roland founder Ikutaro Kakehashi.

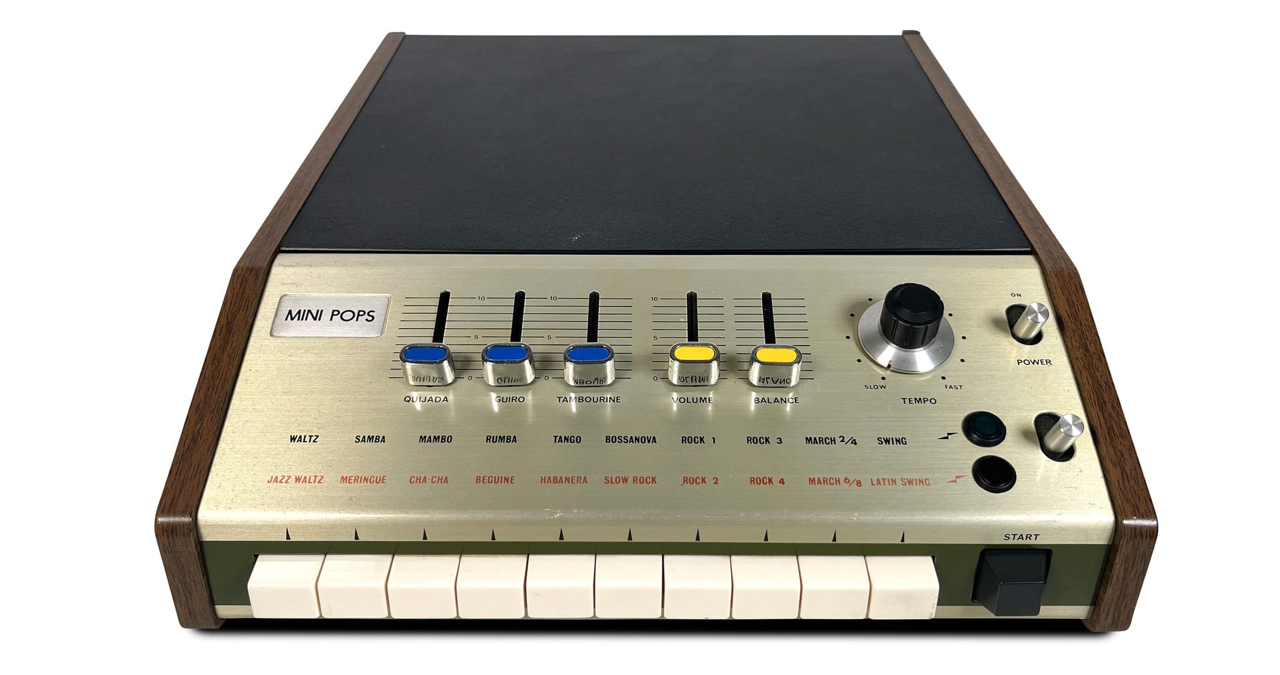

Among the glut of early, basic releases came the Ace Tone FR-1 Rhythm Ace. Simple controls on the front of the sturdy, analog circuit-packed, box enabled users to switch between preset genre-aligned rhythms (rock, samba, waltz, swing), set the tempo and choose between different patterns within the currently selected rhythm. Pretty innovative for its time.

It would be this particular drum machine that the Bee Gees’ Robin Gibb - then in the midst of a short-lived solo career - leaned on when working on his 1969 solo hit, Saved by the Bell.

It's this song that is regarded by many as the first popular song to include a drum machine in its mix.

While Gibb’s haunting, string-soaked ballad is a gorgeous slice of dreamy 1960s pop in its own right, the underpinning of the FR-1's steady pulsing beat adds a further out-of-time quality, especially when listened to in retrospect.

Saved by the Bell was the first single of Robin’s brief 1969 solo career.

Going it alone seemed like an odd move in the wake of the Bee Gees' first flurry of success (which included New York Mining Disaster 1941 and I Started a Joke).

Though still some way off their mid 70s disco pomp, these early triumphs thrust the brothers (and their songwriting/vocal prowess) into the spotlight. Tensions had begun to bubble internally, and the added pressure of sudden fame ultimately caused Robin to suffer from nervous exhaustion.

“That was a period where we [fellow Bee Gees and brothers Maurice and Barry] had tremendous egos for success where we just stopped talking to each other,” Robin told NPR. “We had people saying that 'you're responsible for the success of the group,' and 'he's successful,' so we all had our own sort of court”

Though the Gibbs would reunite at the dawn of the 1970s, just in time to morph into key figureheads of the burgeoning disco revolution, during the early part of 1969, Robin Gibb was an independent agent.

At that time, Robin’s solo recording approach was to record himself playing organ alongside the FR-1, adding guitar and vocals after the core bedrock was established.

Robin's drum machine and organ set-up is pretty analogous to today's click-track sync'd, MIDI-keyboard-originating DAW projects, but back in the 1960s was quite a unique way of working, as studios were largely still set-up for recording live bands. (and drummers).

At the time, using a standalone drum machine in this way was quite a new innovation, with the Wurlitzer Side Man (released a decade earlier) a typical go-to for electric piano players’ rhythmic duties.

A few years prior to Gibb using the FR-1, Korg's Donca Matic DE-20 and Mini Pops drum machines became commercially available. These further expanded on the simple clicks and clangs of their predecessors with more lifelike sounds. These units featured expanded controls which users could wrangle to build their own fills and unqiue patterns.

The FR-1 was released in this same marketplace context, and enabled users - for the first time ever - to combine these preset beats and solo or remove certain drum elements.

According to The Cambridge Companion to Percussion, Gibb used the FR-1’s ‘Slow Rock 12/8 rhythm preset, which you can clearly hear during the song’s introduction prior to the first verse (after the lush string flourish at the start).

The song itself evokes the types of emotionally heavy balladeering of the previous decade. But it's that constant drum machine pulse which signposts the future.

The song would soon feature on Robin Gibb’s debut solo album, Robin’s Reign. Over the course of the album's eleven tracks, the drum machine would periodically re-appear. Though Gibb said little about using the drum machine use in later years, its clear that he felt it was adding something to his songs.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In fact, the FR-1 is the very first thing you hear on the record, as it precedes the intro to album opener, August October.

Yet, while Saved by the Bell - released on the 27th June 1969 - is certainly the first pop hit to feature an electronic drum machine throughout its run-time (the track hit the #2 in the UK charts, despite a poor performance in the US), the forebears to the drum machine had featured on record before.

In 1968, the United States of America’s one and only studio album sported several preset-led drum machines, amid a soup of innovative technical feats. But, despite acclaim in avant garde circles, didn't connect in either the UK (where it didn't chart) or the US, where it remained in the chart's outer reaches.

A scant two years later, Sly and the Family Stone would further push the drum machine into the ears of listeners around the globe, with the US number one hit Family Affair prominently sporting the Maestro Rhythm King MK IV as a central part of the mix.

Arguably, it was that track that really 'defined' the drum machine as a rhythmic backdrop of a funky, danceable song. But that doesn't meant that credit shouldn't go to Robin for being the first to include it in the context of a pop song.

Within a year, Robin had reunited with his brothers in the Bee Gees. They would, of course, go on to become one of the most significant acts in music history, selling over 220 million records, spawning nine number one US hits, and grabbing five Grammys along the way.

With these mountainous achievements just around the corner, Robin's short-lived solo career tended to get maligned as a temporary blip - a confused pit-stop before the three permanently reconciled and became disco titans.

Yet, aside from it being notable for yielding the first drum machine-based pop hit, the creative fruition of this period has been re-appraised, especially in the wake of Robin's sad death in 2012.

The Guardian’s Alexis Petredis is a particularly eloquent exponent of this era. “[It’s some of the] weirdest, most fascinating music of the sixties," Petredis stated in a video review of a boxset collating Robin's solo work. "The orchestration is marooned over this primitive drum machine, thudding away. It’s fascinating, it’s chilling, it’s the product of an utterly unique mind.”

I'm the Music-Making Editor of MusicRadar, and I am keen to explore the stories that affect all music-makers - whether they're just starting or are at an advanced level. I write, commission and edit content around the wider world of music creation, as well as penning deep-dives into the essentials of production, genre and theory. As the former editor of Computer Music, I aim to bring the same knowledge and experience that underpinned that magazine to the editorial I write, but I'm very eager to engage with new and emerging writers to cover the topics that resonate with them. My career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website, consulting on SEO/editorial practice and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut. When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“How daring to have a long intro before he’s even singing. It’s like psychedelic Mozart”: With The Rose Of Laura Nyro, Elton John and Brandi Carlile are paying tribute to both a 'forgotten' songwriter and the lost art of the long song intro

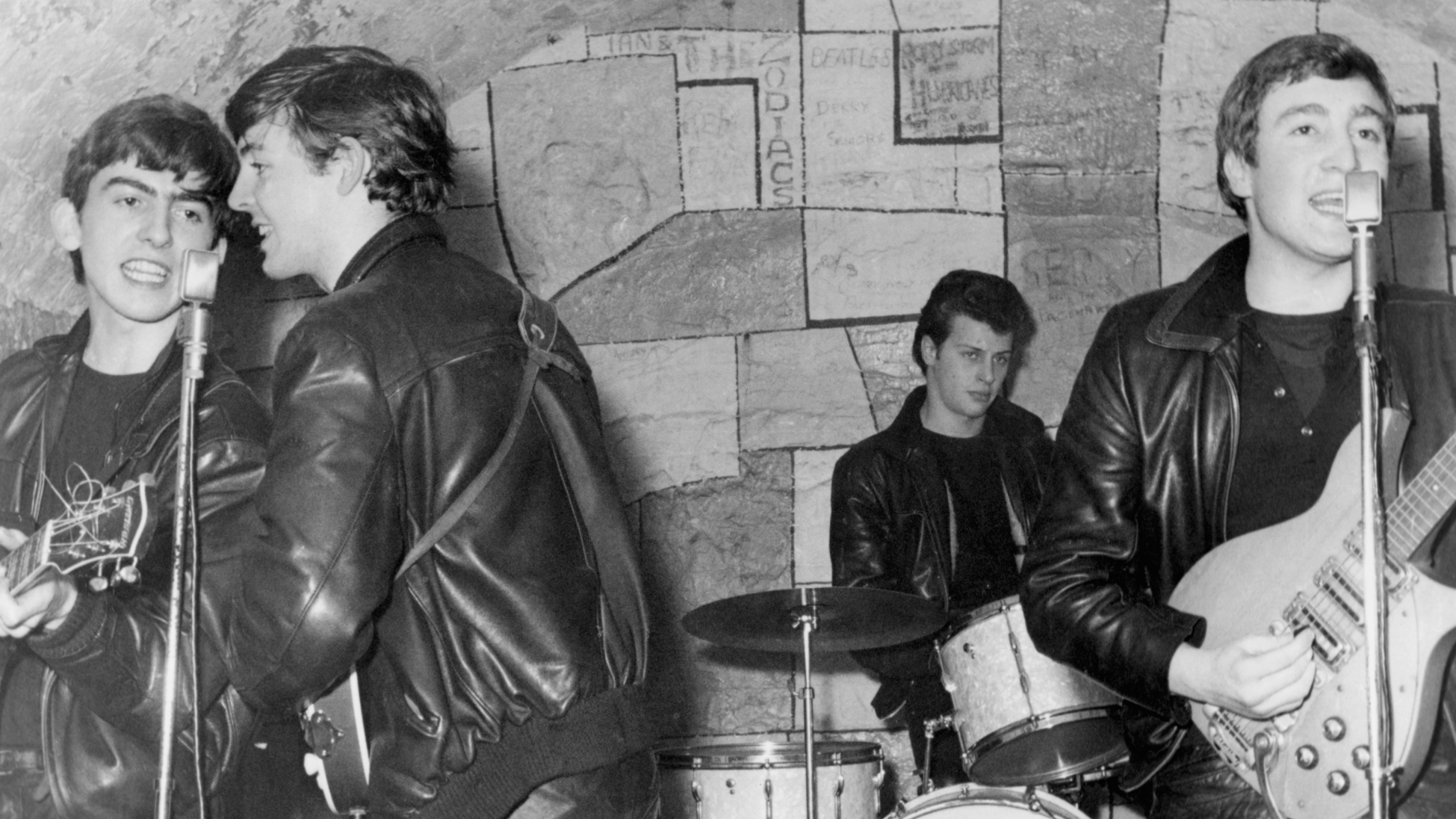

“I had a blast. Thank you”: Original Beatles drummer Pete Best retires, aged 83

![James Hetfield [left] and Kirk Hammett harmonise solos as they perform live with Metallica in 1988. Hammett plays a Jackson Rhodes, Hetfield has his trusty white Explorer.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/mpZgd7e7YSCLwb7LuqPpbi.jpg)