“I wondered if I was insane for wanting to do this”: How Def Leppard drummer Rick Allen learned to play again after losing his left arm

The full story of his heroic comeback

On the morning of New Year’s Day 1985, Def Leppard singer Joe Elliott was at his house in Cobham, Surrey, with his parents visiting, when he received a phone call from the band’s co-manager Peter Mensch. This was not a social call. Mensch was telling Joe that something terrible had happened to Rick Allen, Def Leppard’s drummer.

At first, Joe could not believe what he was hearing: “Rick’s crashed his car,” Mensch said. “And he’s lost his arm.”

As Joe would recall, “After I got off the phone I was just bawling my eyes out. My dad put his hands on my shoulders and stuck this whisky in front of me and said, ‘Drink it’. I was sitting in this chair, crying and thinking, God almighty…”

On the the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, Rick Allen had been driving his new black Corvette Stingray on a country lane just off the A57 near Sheffield. In the passenger seat was his Dutch girlfriend Miriam.

Rick had lost control of the car on a sharp bend. It smashed through a dry-stone wall and rolled down into a field. His seatbelt hadn’t been securely fastened: he was thrown from the vehicle, but his left arm remained inside, torn off at the shoulder. Miriam was trapped in the car, dazed, but without serious injury.

When the ambulance crew reached him, Rick was still conscious and in deep shock. This had stemmed the bleeding from his shoulder, and it saved him. The first words he heard were from a medic: “You’re still alive.”

Rick would recall of what happened: “The only way I can describe it is that you go into a kind of a survival mode where all your normal senses shut down. Whatever consciousness is there, all it’s bothered about is surviving. You just go to this place where there’s no pain, and in that place you’re able to decide whether you’re better off dying or staying here.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“As I was taken to the hospital, I remember being above the ambulance and observing the whole scene, and then coming back in, a kind of integration. It’s beyond words, beyond understanding, a mystical experience.”

It was at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield that Rick’s condition was stabilised and his arm reattached. The first person to arrive at the accident scene had been a midwife who lived nearby; she had packed the arm in ice that she had ready for her New Year party.

The morning after, with Rick’s family at the hospital, the first to join them was the band’s bassist Rick ‘Sav’ Savage, who had also been at home in Sheffield. When he saw Rick unconscious in a hospital bed, he was devastated. “I went numb,” Sav said. “My first reaction was, that’s it, he’s finished...”

Rick Allen had turned twenty-one just eight weeks earlier.

Joe Elliott had arrived at the hospital in that evening. Rick had been administered morphine and was slipping in and out of consciousness as Joe sat at his bedside. The following day, surgeons had to remove Rick’s left arm; the wound had become infected with gangrene.

As Joe recalled: “That was my lowest point. I thought, My God, how cruel! To get it back and then have it taken it away again.”

Joe kept reminding himself that it could have been worse. Rick had come close to dying. And during the first 24 hours after the accident, it was feared he would lose both arms; his right arm had been broken almost beyond repair. But this arm would heal. Rick was young and strong. Doctors were sure he would recover and be out of hospital in six months.

But still, the questions turned in Joe’s head: “What’s he gonna do? What are we gonna do? Do we get another drummer? None of us wanted that.”

On January 4, Rick regained full consciousness. He assured Joe, “I’ll be fine,” although in his heart he didn’t believe it. As he later admitted, “I didn’t think I’d be able to do anything again.”

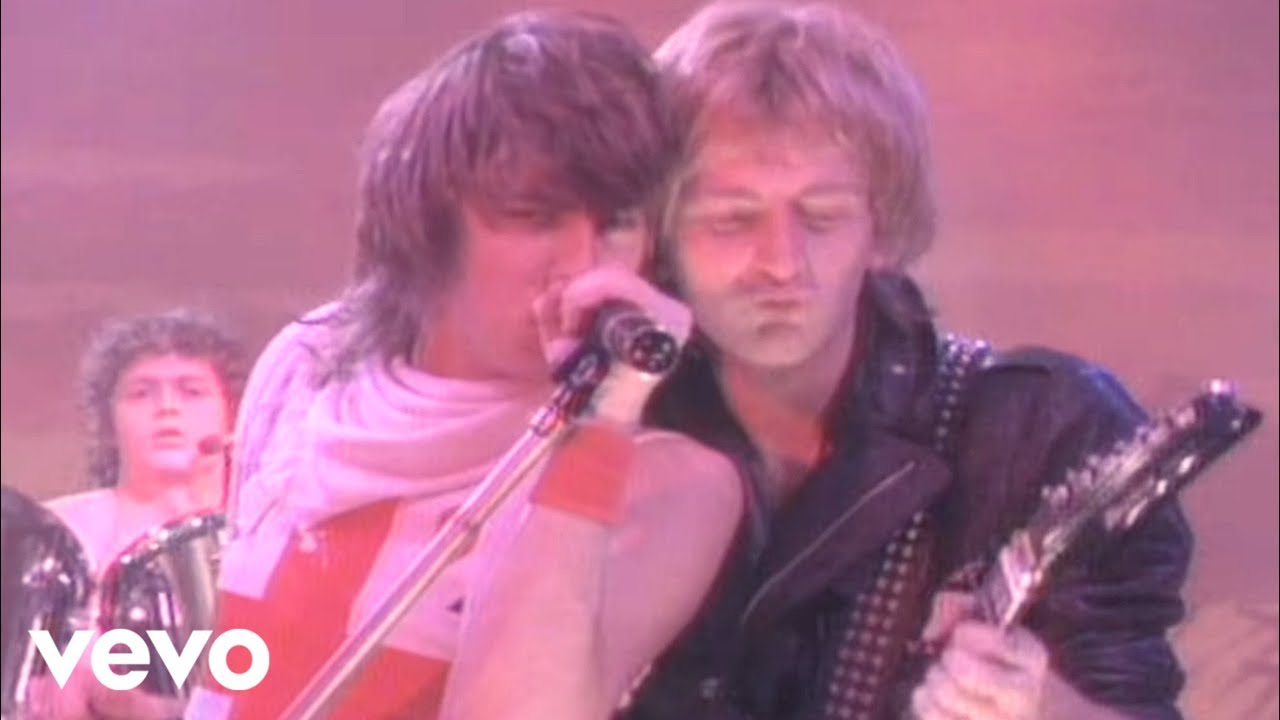

But he gave the band his blessing to get back to work without him, as they tried to finish the album Hysteria. With some reluctance, they agreed. The next day, Joe, Sav and guitarists Steve Clark and Phil Collen returned to Wisseloord Studios in Holland.

Whatever the future held for Rick Allen and Def Leppard, there was at least one certainty. As Joe put it, “Rick was in the band until he said he wasn’t.”

This was confirmed during the band’s second day back at Wisseloord, when they received the first of several phone calls from drummers requesting an audition. “Some American guy,” Joe sneers. “Hey man, I hear you need a new drummer. Well, I got two words for you, pal: f**k off!”

Rick had a CD player in his hospital room. At first, he found it hard listening to music. “It reminded me of what I used to do,” he said. “What I wasn’t able to do anymore.”

But soon, intuitively, he started tapping out rhythms with his feet against the foam block at the foot of his bed, placed there by a nurse to keep his body from sliding.

In the second week of January, Rick was visited by ‘Mutt’ Lange, the producer whom Def Leppard called “our sixth member”.

Lange had produced and co-written the band’s multi-million selling 1983 album Pyromania.

Lange had also co-written the songs for Hysteria. But after years of working non-stop on albums for AC/DC, Foreigner and The Cars as well as Def Leppard, Lange had said he was burned out and couldn’t commit to producing Hysteria. And then, when he visited Rick Allen, everything changed.

Mutt was convinced that Rick could still play drums. He explained how modern technology could help Rick: how an electronic drum kit would allow him to replicate patterns using his right hand and left foot that he would previously have played with two hands. “Mutt was just fantastic,” Rick said.

While designers at the Simmons drum company set to work on making this new kit, Rick made rapid progress in his physical rehabilitation. Just two weeks after the accident he made his first attempt at standing up; unbalanced, he fell to the floor. A week later he’d learned how to walk again, how to shift his weight to steady himself. He developed new life skills: how to eat with one hand, to brush his teeth and tie his shoes.

Mutt sat with Rick for many hours, always offering encouragement. And during one visit, Rick asked him if he’d consider producing the new album, which they had been working on since the summer of 1984 - first, with Jim Steinman, writer of Meat Loaf’s Bat Out Of Hell, who was quickly removed from the project, and then with Nigel Green, Lange’s right-hand man.

As Rick recalled: “I just said to him Mutt, ‘We really need your help. We’re not a good place at the moment. Would you spend some time with us and see if we can’t get this record made?’ I think it was a combination of things that pulled him back in. And it was the best thing that could have happened.”

Rick was discharged from hospital after six weeks, not the six months his doctors had predicted. And after a further two weeks at his parents’ home in Sheffield, he could wait no longer and flew out to join the band at Wisseloord.

His new kit had been set up in Studio 4. Every day for three weeks he would practise alone while the band worked with Mutt and Nigel Green in Studio 2.

Rick would meet the others for coffee breaks, but at all other times the door to Studio 4 was firmly shut.

“He’d be in there just playing and playing and playing,” Joe said. “He wanted to make all the mistakes on his own. And then he called us all in one day and said, ‘Listen to this.’”

Rick played to a classic Led Zeppelin song.

“He played When The Levee Breaks,” Joe said, “and we all ended up crying. And from that moment onwards, I think we all started to believe.”

What helped Rick in developing a new way of playing drums was that he had already experimented on Pyromania. “We’d run all the tracks with a drum machine,” he explained, “and then I would come in and play over the top – with just percussion or full kit. Nobody had ever really done that before.”

Now he would reinvent himself again, with a new mindset. “One of the best things that happened to me,” he said, “was I stopped comparing myself to how I used to be, and comparing myself to others. Once I’d accepted the fact that this was a really unique way of playing, it freed me completely. I didn’t feel less-than. This is who I am. This is how I’ve got to do it.”

Rick Allen’s comeback was complete when, in the summer of 1986, Def Leppard took time out from recording Hysteria to play European festival shows.

“It seemed like we were always in the studio,” Joe said. “We needed to get out into the world, to re-energize ourselves. And it was one of the best decisions we ever made.”

First, the band rehearsed for a month in a Dublin suburb, with Status Quo’s Jeff Rich enlisted as a second drummer. As Rick Allen conceded, “Nobody, myself included, was 100% sure I could play a whole show.”

The newly expanded band was road-tested with low-key warm-up gigs in Irish clubs. The first three ran smoothly, with Rick coping well with his new electronic kit. But when they reached Ballybunion in County Kerry, there was a problem: Jeff Rich, having flown to the UK for a Quo gig, had his return flight delayed by fog.

There was no choice but to cancel or go on without him. Rick chose the latter. The band were 40 minutes into their set when Jeff arrived and jumped behind his kit. Joe recalled: “I turned around to get a drink, saw Jeff and went, ‘Oh, I didn’t even know you were here!’ So Rick had really carried it.”

On the following night, in Waterford, the stage was too small to accommodate two kits. Rick was asked, ‘Do you want to have a go on your own?’ His reply: ‘F**k yeah!’”

With Jeff Rich looking on, Rick played even better. After the show, the two drummers embraced before Jeff said, smiling, “I guess I’ll be going home tomorrow, then.”

Even so, Rick was filled with doubt ahead of the first festival show on August 16: Monsters of Rock at Donington Park in Leicestershire. “I wondered,” he admitted, “if I was insane for wanting to do this.”

Def Leppard performed in the late afternoon, following Motörhead and ahead of the Scorpions and headliner Ozzy Osbourne.

As an audience 70,000 awaited them, Rick was shaking. “I was in a bit of a bubble,” he said. “I was hyper-focused on what it was I was doing.”

It had been decided beforehand that Joe would not say anything to the audience about Rick, but at the end of the band’s set, they were called back for an encore, and Joe said to Phil Collen, “I’ve got to do this.”

As Leppard blasted out a version of the Creedence Clearwater Revival song Travelin’ Band, Joe said simply: “Mister Rick Allen on the drums.”

The response was an ovation so loud that Joe felt the air move. “It blew your hair back,” he said.

Such was the depth of emotion conveyed in that moment that Rick was overwhelmed. “I cried so much I needed a bucket!” he said. “It was such a release from all these pent-up emotions, and such a confirmation for me. It was fantastic, and it stays with me always.”

It was a full year later that the Hysteria album was released. It went on to become one of the biggest selling albums of all time.

What that album represented to Rick Allen was profound. He summed it up one word: “Rebirth.”

Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”