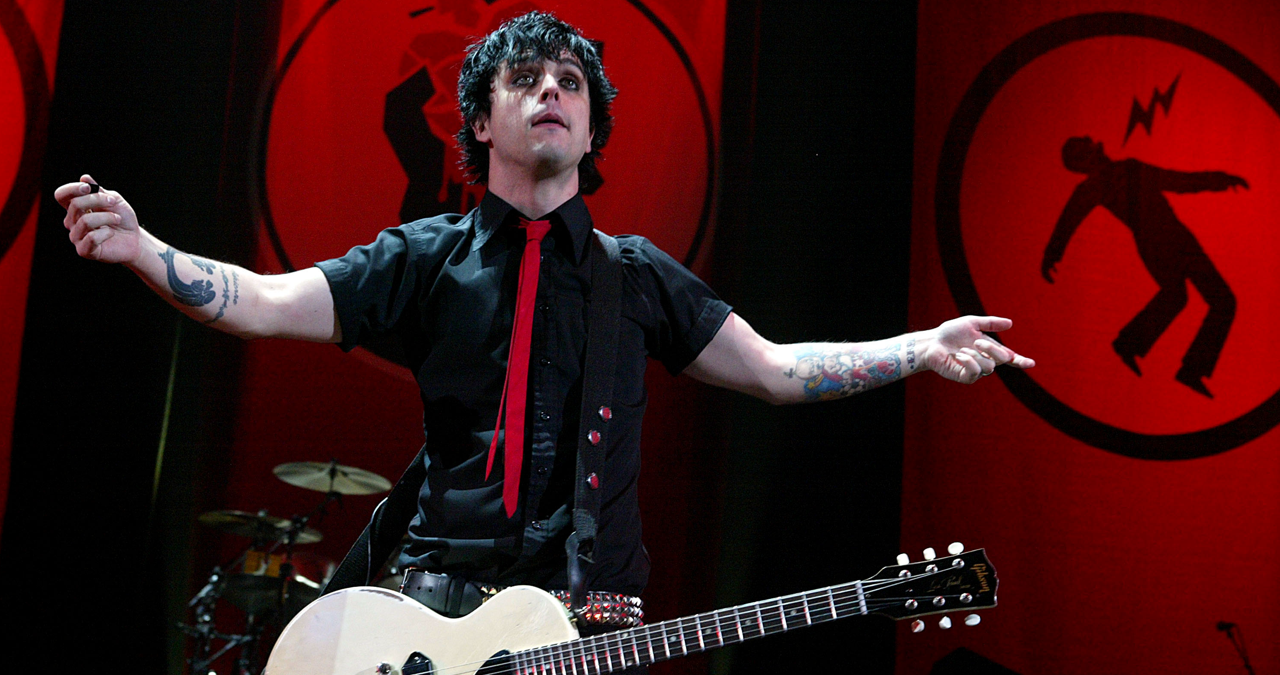

“I used everything I knew about music”: How Green Day exceeded expectations with their most ambitious song

The sprawling 2004 epic reflected Billie Joe Armstrong’s own lived experiences - and was the cornerstone of American Idiot

As one of the world’s biggest pop punk outfits, Green Day have endured a fair share of ups and downs across their 38-year career.

Their highs have been very high indeed. There’s the cherished status that their beloved mid-90s triumvirate Dookie, Insomniac and Nimrod still hold. Then there's their consistent ability to put on a hell of a live rock show.

Yet the lows (misguided 2012 trilogy Uno…Dos…Tré! springs to mind) have been grimace-inducing.

But perhaps their single greatest moment on record was crafted in the wake of one of Green Day's bleakest periods.

The song - Jesus of Suburbia - was the thematic keystone of their punchy 2004 Grammy-winning monolith American Idiot. The record that set a progressive mould for mainstream punk in the 2000s.

A staggering feat of creative audacity, Jesus of Suburbia left many who'd hastily called time on the Californian three red in the face.

The Song: Green Day - Jesus of Suburbia

The Magic Moment(s): Really, it's the impact of the entire, multi-part structure of the 9:08 length track. If we had to pick - it’s got to be the All the Young Dudes-recalling second movement beginning at 1:55

The Origin

Since their 1994 major-label breakthrough Dookie, Green Day had ascended into an arch-figurehead position atop the pop punk universe. To many mid-90s teens, they came to occupy a hole in the alternative scene recently (and tragically) vacated by Nirvana.

Once the Bay Area’s principal hell-raisers, Billie Joe Armstrong, Mike Dirnt and Tré Cool's teenage band had surprisingly found itself becoming a household name across America.

Radio-friendly monster hits, adroitly produced by Rob Cavallo, were to thank. From the jittery euphoria of Basket Case to the bittersweet romance of the acoustic-wrought Good Riddance (Time of Your Life).

But, by the early 2000s, Green Day was beginning to feel like it was running out of road.

Though 2000’s Warning was by no means a weak album creatively, it found the three lean towards a more acoustic-centric, folkier direction, as evidenced by the Kinks-inspired title track.

It had left many on the alternative-end of the band’s fanbase fearing for the worst. To them, it seemed, Green Day were steadying into MOR territory.

Flagging sales bore this out, with Warning marking a notable commercial disappointment.

But as anyone who attended any of their Warning-era tour shows (as this writer did), will tell you - Green Day’s potency as a live act was still on point.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Yet while the band’s hardcore - and increasingly ageing - fans continued to revel in their iconic 90s hits, Green Day were musing on their next steps.

The tepid response to the newer material (and the fact that they felt the need to put out a sales-recouping greatest hits compilation) could be seen as a portent of the former firebrands' slide into a (comfortable) afterlife as a festival-bothering legacy act. Living off the bones of yesteryear.

Considering this a fate worse than death. Armstrong and co - then heading into their early 30s - mooted breaking up.

“Breaking up was an option,” Mike Dirnt told Rolling Stone in 2005. “We were arguing a lot and we were miserable. We needed to shift directions.”

After a lengthy period of healing their strained personal relationships, the three men re-focused on how 2000s Green Day should operate. Soon after, the band began to map out their next studio move.

Though an initial attempt at a Warning follow-up - dubbed Cigarettes and Valentines - was attempted (and nearly completed) the theft of 20 of its demos drew the project to a halt.

Not a good start. But fate was nudging the band towards something that would be much more special…

Cigarettes and Valentines was never going to be it.

Hitting up their erstwhile production mastermind Rob Cavello (who had been notably absent during Warning) turned out to be a crucial move.

“[Rob] said something to me that was really inspiring,” Armstrong told our sister website, Guitar World. “He was like, ‘Let’s make something that’s just monumental. Do things that you haven’t done before. Just fucking go for it and make an epic statement.’”

Setting themselves the bizzare, Eno-esque challenge of making a smorgasbord of 30-second-length songs, the group discovered that stitching the best of these nuggets together could result in something tremendous.

But it took Armstrong’s penning of the developing record’s iconic George Bush-directed title track - American Idiot - to re-light Green Day’s then-dormant punk fire.

With Billie Joe's pertinent polemic married to an incendiary power-chord jog, the band saw a route forward into something potentially incredible. Yet wildly ambitious.

The idea of an angry, politically conscious, concept album began to crystallise.

Cribbing from the boundless spirit of the Beatles and the Who, Armstrong sought to document the many ills he saw as rife in early 2000s American life. All playing out under the long shadow of Bush’s ongoing ‘war on terror’. Then beaming into homes via increasingly propagandised news networks.

Giddied-up by this through-line, a creative conveyor belt of brilliance began to roll.

Among them, the righteous venom of the glam-stomping Holiday, the stadium-ready power ballad Boulevard of Broken Dreams and the lighter-in-the-air, emotive hymn Wake Me Up When September Ends - A rival to Good Riddance in the tear-jerking stakes.

They were songs that would sit among the band’s finest ever. And they were pouring out at an incredible rate.

But what would be the album’s creative highpoint - and a towering example of a band evolving way out of their comfort zone - was the record’s second cut. The near-ten minute musical and thematic whirlwind of Jesus of Suburbia.

“I used everything I knew about music. Showtunes, musicals like Grease and the struggle between right and wrong, [U2’s] The Joshua Tree,” Armstrong told Rolling Stone “I tried to soak in everything and make it Green Day.”.

Comprising five distinct movements, the Bohemian Rhapsody-inspired suite documented its titular character’s stagnation within his small-town community.

Longing to escape, 'Jesus' packs his bag and heads for the city - putting his confined suburban existence in the rear-view mirror.

Its motifs of aspiration and ambition neatly mirrored its creators’ intent to leave their own safe space, and endeavour for something bigger.

Hammering into being with a barrage of power chords in C# major, Jesus of Suburbia’s first of five sections asserted its concept.

Depicting the title character’s inert existence, subsiding on ‘soda-pop and Ritalin’, Jesus longs for better things - and to escape from the hell of mundanity.

Then, the song reared up into its second-section - an arms-in-the-air anthem, that (undoubtedly purposefully) doffed its cap to Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and All the Young Dudes, as well as Bryan Adams’ Summer of 69.

Armstrong elevated the narrative - framing Jesus’s small-town life with suitably apocalyptic dread:

City of the dead

At the end of another lost highway

Signs misleading to nowhere

City of the damned

Lost children with dirty faces today

No one really seems to care

After a punchy interlude (with the repeated refrain ‘I don’t care if you don’t) Armstrong contorted his vocal into quite the most abrasive snarl committed to record since the darkest corners of 1995's Insomniac.

During this section, the central conceit of the song - and the entire American Idiot record itself - was proclaimed.

We are the kids of war and peace

From Anaheim to the Middle East

We are the stories and disciples of

The Jesus of Suburbia

Jesus isn’t just a hypothetical ‘Tommy’-esque concept record protagonist. His stylised life reflected the discontent of a generation, coming of age in the early 2000s.

It's a generation who might have been too young to experience Green Day's first wave, but, listening closely to Jesus of Suburbia, saw their avatars clearly within Armstrong's narrative.

The pace slowed for the fourth-section’s spine-tingling shuffle, before exploding outwards into a triumphant, victory-lap of a closing section.

With the energy at its most intense, our hero prepares to ‘leave behind the hurricane of fucking lies’ for the final time, and finally exit the ‘town that don’t exist’.

A gentle piano coda heralded Jesus of Suburbia's cacophonous finale. Concluding Green Day’s most audacious - and most brilliant - song.

“It felt like I was in uncharted territory, really for the first time,” Armstrong told Rolling Stone. “I’d taken my songwriting to another level. It starts almost doo-woppy, and then it ends up almost going into this sort of Black Sabbath direction. It’s kind of around-the-world-in-eight-minutes or something. And Jesus of Suburbia ended up becoming the character that ran throughout the entire album.”

“You listen to that as the second song on an album and you think, ‘What the fuck is happening?!” Producer Rob Cavallo commented to Kerrang!.

As a listener and (somewhat lapsed) Green Day fan at the time, this writer can confirm that's exactly how we felt.

Why It's Brilliant

American Idiot, and particularly Jesus of Suburbia, demonstrated that Green Day’s scope and musicianship was far more expansive than anyone had previously realised.

It’s tempting to sniff at artists that try to evolve beyond the niche they're known for, but Jesus of Suburbia worked precisely because its musical boldness was married to a lyric and concept propelled by Armstrong's raw honesty.

Nothing had changed on that front.

Armstrong remained as pointedly and brutally self-reflective as ever he was on 1994’s teenage-angst-ridden Dookie. Jesus of Suburbia marked a natural evolution of that same spirit.

As Armstrong has subsequently stated in an interview with Vulture, the epic is - unsurprisingly - entirely autobiographical. “I mean, I’m tooting my own horn, but I think it encompasses so much about my life and friendship and family, and it’s flamboyant and big and bombastic. It’s one of those moments where I was feeling like I wanted to take a big risk. It’s so fun to play live, seeing how the entire crowd sings along”.

Though the track was released as a single later in American Idiot’s marketing cycle, it was really the impact of hearing this song in situ on the mega-selling American Idiot, that was a stop-in-your-tracks moment.

Recapturing the bite that had been lacking since around the late '90s, Green Day had finally become that rarest of things; a globally successful, and Grammy Award-winning, punk band delivering incisive commentary on both the current state of politics and society.

And, a new generation - identifying themselves with Jesus and the rest of Armstrong's cast of outsiders - were reeled in.

Green Day had been the outliers as the pop punk marketplace began to become increasingly filled with frat-boy-antics, but Jesus of Suburbia (and its twin ‘long’ song on the record, Homecoming) pointed to a new progressive, bolder route. Many acts would soon align with it.

It lay down the gauntlet for the operatic daring and eyeliner-clad extravagances of emo-era artists like My Chemical Romance and Fall Out Boy a few years later.

“I don’t know, when you hear a record that’s important and that is resonating, it’s almost as if a bell goes off inside your head.” Armstrong told Kerrang. “It’s just a funny feeling that I get. You can feel it in your body. I just knew that when we released it, people were going to respond and explode.”

I'm the Music-Making Editor of MusicRadar, and I am keen to explore the stories that affect all music-makers - whether they're just starting or are at an advanced level. I write, commission and edit content around the wider world of music creation, as well as penning deep-dives into the essentials of production, genre and theory. As the former editor of Computer Music, I aim to bring the same knowledge and experience that underpinned that magazine to the editorial I write, but I'm very eager to engage with new and emerging writers to cover the topics that resonate with them. My career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website, consulting on SEO/editorial practice and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut. When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Green Day - Jesus Of Suburbia [Official Music Video] [4K Upgrade] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/fZFmaMbkUD4/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Green Day - American Idiot [Official Music Video] [4K Upgrade] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/Ee_uujKuJMI/maxresdefault.jpg)

![James Hetfield [left] and Kirk Hammett harmonise solos as they perform live with Metallica in 1988. Hammett plays a Jackson Rhodes, Hetfield has his trusty white Explorer.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/mpZgd7e7YSCLwb7LuqPpbi.jpg)