“I’ve always enjoyed working in an area where I feel out of control. I’m definitely more creative in that situation”: Thomas Dolby tells us about pushing himself in the studio - and inspiring the next generation

After 40 years at the cutting edge, Dolby is now prepping his students to take on the future

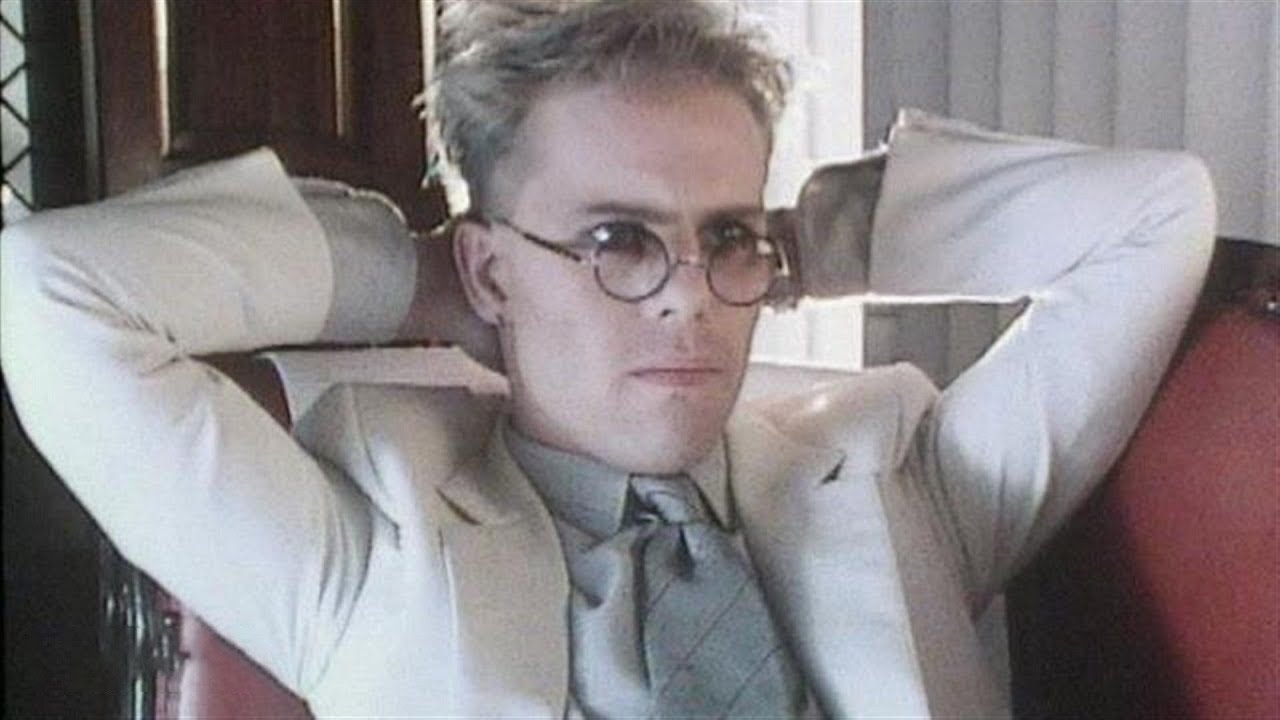

PRODUCER WEEK 2025: It’s safe to say that Thomas Dolby is a man of many talents. Always an audio-visual pioneer, Dolby famously conceived the video for his breakthrough MTV hit She Blinded Me With Science before writing the song, creating it later, to fit with his visual ideas.

After moving to the States in the 90s, Dolby found himself at the centre of silicon valley’s booming internet culture, playing a vital part in developing audio tech mobile phones.

Now, while still touring and experimenting with music, and recently writing his first novel, Dolby has embarked on another new career, this time teaching students the art of film scoring, inspiring them to take similarly brave creative leaps.

We caught up with him during a break from the day job to talk synths and so much more, past, present and future…

MusicRadar: Hi Thomas. Where are you at right now?

Thomas Dolby: "I'm in Baltimore, Maryland."

MR: And is that where you're teaching?

TD: "Yeah, I teach at The Peabody Conservatory, which is a part of Johns Hopkins University.

"I teach film and game music, teaching young composers to compose for picture, whether it's film, TV, VR or video games.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"This is a generation who roll their sleeves up and dive in there. Whereas previous generations maybe felt that they needed to go get a music degree first and then go do a master's in composing or orchestration or whatever, the current students don't want to wait till their mid-twenties to get into the industry."

MR: And what kind of things are the current students into?

TD: "They’re into Studio Ghibli… They're into How to Train Your Dragon… And a lot of video games that I've never heard of.

"They're [also] into Hans Zimmer and Ludwig Göransson… People who are pushing the envelope, and they have respect for. [As well as] classic 20th century film composers, John Williams, Bernard Herrmann."

MR: How do you feel about them embracing technology to make their music? Do you think that they might not be working as hard as you and I did back in the day?

TD: "Well, although you and I had to work very hard, it was also a rarefied air. The equipment was expensive and unreliable.

"This was an era where one in three households had a guitar, but synthesisers were still very rare and precious. So inevitably we felt like pioneers because there were really only a handful of people with access to the top gear.

"I was the first kid on the block to get a monophonic synthesiser and the first to be able to afford a polyphonic synthesiser. And then a sampler and then a computer and so on.

"At each stage I felt like one of only a small number of people who were diving in and finding out what was possible."

"And now, of course, there’s a wealth of different kit available, and at pretty affordable prices from free on up. So I welcome the fact that the barrier to entry is down and anybody can have a go.

"But the flip side is that convenience is now often first and foremost - just hit a few knobs and get a great sound - and I think that the values and the skills that we had to develop to make the best of what we had are still important.

"So this is very much a focus of my teaching. I give them limited resources and they have to turn off their phones and the internet and just make something spontaneous with what's available to them."

MR: You touched on your early beginnings with a synth there. What was your first and where did you go from there?

TD: "It was a Wurlitzer electric piano… Then a Solina String Ensemble… The guts of a Transcendent 2000 kit synth… Then a Micro Moog… And then I think a Fender Rhodes. And then a Roland JP4 and soon after a JP8.

"Then a PPG 340/380 Wave Computer called Henry, that was the size of a refrigerator. Then it got a bit lighter when I went down to a PPG Wave. And a Fairlight.

MR: Any favourites in there?

TD: "The PPG. It had a very distinct sound to it. And as an exploration device, the original Fairlight was fascinating. There had been sequencers that you could have in your back room, but that was the first time that you could really make a record there.

"Neither of them had a set way to use them. I think with the later significant advances in synths, almost as soon as you got them, you had exemplars of how to use them.

"A good case in point was the [Yamaha] DX7. I think every record producer in London and New York and LA had a DX7 within a space of about six months. And you were hearing it all over pop hits. So you’d start flipping through the presets and you find those sounds… So you’d buy into the idea that that was the way to use it.

"But in the early days of the Fairlight that wasn’t the case.

"I think Richard Branson made a Christmas record with a sheep bah-ing, but when Peter Gabriel or Kate Bush or Art of Noise or whoever got it, everybody found a different way to use it. That was very inspiring. "

MR: Do you still have yours?

TD: "My first Fairlight I bought for £80,000. My first record advance was £100,000 and £80,000 of that went on the Fairlight. The other twenty bought me a flat in central London.

"Obviously, if I’d have bought five flats in central London at this point… Anyway, it gave you the knowledge that you were in that rarefied air - that if you came up with an interesting use for Fairlight then you were almost certainly the only person in the world that had that. So that was a very privileged position to be in.

"In the end I gave mine back to the Fairlight Museum in Sydney. It spent a number of years in flight cases in a shed in my back garden in California. The shed was locked up for a long time and the creepers and vines had grown up through the wooden floor and found their way into the mainframe chassis full of circuit boards.

"It was like the earth was getting revenge for the samples of trees being felled that I used on Mulu The Rainforest. It fought back.

MR: You’re still touring. Do you think that electronic artists have had to work that bit harder when it comes to live shows?

TD: "Yeah, it's certainly fair to say. In a certain way we’ve always had a bit of an inferiority complex. Unlike a guitar or a drum kit, we can't really ‘shred'.

"I think that we tended to indulge the fact that ‘it's complicated, making these sounds’. So we would use the stage to recreate that experiment and that the audience were there to witness it in real time and the risks that go along with that.

"In the past I had some analogue sequencers and I had some weird hybrid equipment. When I was in San Francisco, I would go on eBay and find some sort of piece of signal measuring equipment from the US Air Force or something and I had a guy who would gut it for me and replace it with MIDI pots so I could use it as a controller on stage.

"But that's not very sustainable. It's a lot easier to just use good old USB cables so that if something breaks, you can nip next door to the supermarket and pick up another at 3pm on a Sunday.

"But there's always been a sort of visual layer to what I do and it makes it more interesting for the audience than just watching a guy twiddle knobs.

"I was always more motivated by the fear of everything coming crashing down and looking like a tit than I was by the possible glory of an epic win at the end of a concert where everybody's on their feet. Fear of failure was really what got me through!"

MR: And now that we’ve finally conquered the technology do you think that we have too much control? Too many opportunities to keep tweaking rather than actually making music?

TD: "Yeah, maybe. ‘Too much control’… I don't know. I've always enjoyed working in an area where I feel out of control, you know? I'm definitely more creative in that situation. Whether it's using a musical device that I don't understand yet. Or working in a genre that’s not really native to me.

"I think over the years, starting with electronic music but then going on to MTV videos, to production, to working with computers and the internet, web, ringtones, filmmaking, writing novels, teaching at university… Each new field I've gone into I’m really out of control and that's what sparks me.

"I sort of go into atrophy if I find myself working in an area where I do have control and I know what I'm doing. I get bored and uninspired quite quickly.

"It’s like the concept of an album as a unit of output at this moment doesn't really appeal to me. I think if it were something different?… If somebody asked me to contribute something cross-media to do with film or games or VR or AI? Something else? Then that might appeal to me.

"But the old fashioned way of writing an album's worth of material and then going in the studio and putting it out and then going out and touring with it? No, that absolutely doesn't appeal to me at this point."

MR: So the changing times and technology have always been an inspiration for your creativity?

TD: "Yeah, I mean, the PPG Wave? I never really learned that. It just had a little LED screen and a bunch of knobs and a manual in German with lots of very long words and I never really fully understood it.

"There was always the danger that when you were trying to shape a sound, that you’d tweak the wrong knob at the wrong moment and it would suddenly go off the deep end into a completely different domain.

"But I found that very exciting. The fact that I never really learned it. Conversely, I think that Roland synths are very, very logical. From the architecture through to the ergonomics of the knobs and sliders.

"I remember, I did a gig for Roland at the NAMM show a few years ago and they went and found me at Jupiter 4 which must have been 40 years old at that point, and I used it on stage to recreate She Blinded Me With Science, which was mostly done with the Jupiter 4.

"And you know what? Even after all that time away from it, my hand just went to the knobs - I knew exactly what was where. "

"Conversely, with all of those little LED screens, from the end of the 80s, early 90s in a piece of rack mount gear. You crane your neck, you get whiplash, and then you've got to try and flip through these menus and submenus and remember where to find that one parameter…

"And if you spend two or three months away from that box, you have to learn it all over again. "

MR: Are you still making music? Do you have a studio at home?

TD: "Well, I've got a comfortable desk where I put my laptop with a decent pair of speakers in a reasonable sound environment. But I wouldn't call it a studio, no.

"I'm trying to get rid of equipment and hardware, make my wife happy, you know? Make some of those things go away. I rather like the fact that you can do it all in the box these days, and I don't have a gear lust for more little gadgets."

MR: Do you still have your studio in England that you built inside a lifeboat?

TD: "Yeah, so that's still there in England. I close it up for the winter, but I generally go back there for the summer and I'll be heading back there in a few weeks.

"It's in a tiny village, and it’s exposed to the elements, but I open it up in the summer like a summer house and do my work out there. But to me the Roland Cloud emulation stuff is so good that the minor differences between that and what it's emulating are really not worth all of the hassle."

MR: Given your interest in all kinds of tech over the last four decades, how do you feel about where we’re at in 2025? Did everything work out as you expected? Are we on the right trajectory?

TD: "Well, we're on the trajectory that we're on - I'm not somebody that tends to be judgemental about progress and say ‘this is bad’ or ‘it was better in the good old days’. I think that there are people up and coming now who will get their teeth into the new technologies that are available and will show the world how to use them, creatively and use them for good.

"I look at my students. They have the patience and the resilience and the brain capacity to figure out how to use this stuff. I just try to give them some basic attitude to it, because it's so easy for them to cut corners. But that's not where you’ll find your individual voice. Not by using the same convenient time saving devices that everybody else is using.

"I think technology comes in fits and starts really doesn't it? Every few years there seems to be a spurt of energy around VR or whatever.

"Two steps forward and one step back quite often. I think we'll get there in the end. I think that the devices themselves are becoming more and more sci-fi – smart glasses, smart earpieces and maybe even contact lenses, followed by some sort of neural implants. I think that's inevitably going to come about."

MR: Speaking of visions of the future, you were part of the legendary Grammy’s synthesizer medley in 1985, introducing electronic music to America alongside Howard Jones, Herbie Hancock and Stevie Wonder.

TD: "It's funny. It’s one of those things where it shows up on YouTube and it doesn’t quite match your memory of it. I'd forgotten that John Denver introduced us!

"I think that the USA has always been a lot more conservative culturally than the UK. The underground becomes mainstream a lot more rapidly in the UK and when it does, it's everywhere. It's in the stores, it's on the T-shirts, in the clubs and on the radio.

"New ideas can infect the UK a lot quicker. Whereas in the US there's still some state in the middle where they're still discovering things from the first time around. So you don't get ‘retro’ and things don't really invade the common consciousness."

"In the mid-eighties most of mainstream America was still listening to guitar and drum rock on FM radio. And even though by this point MTV had embraced electronic music and straight trousers and short hair, the bulk of the USA was still caught up in the corporate rock of the late 70s.

"So I think what the Grammys were trying to do was introduce a new possibility. Get past the resistance to synths being ‘not being real music’ kind of thing, you know? I think they were trying to get past that by showing some old masters who had adapted to the new technology, with Stevie and Herbie, alongside the young pretenders, me and Howard, that were up and coming. So it was an interesting moment in time."

MR: And what is that instrument you're playing? You have a small box on a strap around your neck…

TD: "I think it was the Roland TB-303. I think I had two. It was the Drumatix [Roland TR-606] and the TB-303. They came as a matching pair."

MR: Is there a new technology out there today that excites you right now?

TD: "I think that AI is exciting. I'm going to bypass the obvious question, which is, ‘Is it going to replace us all’ and instead look at it from this point of view:

"So what I love about assembling a few musicians in a room, and recording them and then sending them home and then sitting back and listening to what I've got - maybe resampling it and rejigging it and using chunks of like building blocks - is that when musicians sit together in a room, they're listening to each other all the time.

"What they play is in response to what they're hearing, both from an improvisation and composition point of view, but also the resonance of the instruments in the room.

"But when I program samplers and drum machines, one sound at a time, each time I move on to the next sound, the new sound has no knowledge of the first sound that I did… It's just trying to obey me in isolation. And it's really up to me to find and create context. It’s like Minecraft.

"But now that I'm working in a conservatory, I'll walk past a room and there's a chamber ensemble playing in there. And, after hours of programming machines, I listen to the sound of centuries old stringed instruments and wind instruments playing together by people who have devoted their lives to mastering the instrument and I just think, ‘Well, I couldn't programme that in a million years’. No matter how high tech and high res the machines get.

"When a violinist plays a note their fingertip on the fret is responding to their brains and their ears and the open strings, and the open strings of the player next to them, and the open piano lid and the timpanis ringing and the sound from under the stage and the sound from the back of the room…

"And everything is happening in real time. When these musicians get truly in tune on every level, it's a miraculous thing that you could never program.

"But AI has the potential, really for the first time, to enable all of those electronic building blocks to actually have an awareness – a consciousness of each other. And I think that is potentially very exciting.

"I don't think I will be part of the generation that will really harness that. I think that that's downstream. It's not just… you know… ‘The Borg’… It’s us. Imbuing the technology with our knowledge and our taste and our wisdom and experience.

"So I like the idea of deep learning devices giving me new creative possibilities that didn't exist before."

MR: Are we heading into an age where everybody is an artist you can just type in a prompt and it will come out of the speakers?

TD: "I think we're pretty much there now. But it’s ‘art with training wheels’ because it will only make its decisions based on somebody else's input. If you describe the song that you want, and it says, ‘OK, well I'm gonna combine elements of Taylor Swift and Drake’ to give you that, do you listen to it and go, ‘Wow. I just made a record’?

"The rate of advancement is really parabolic. I've got students who come in for a weekly lesson, they say, ‘Oh, you have to hear the new rev of [fill in the blank]’. And ‘It's doing more stuff than it's ever done before’… But oddly enough, I don't find that disturbing.

"And the reason why is that there are millions of people in the world that have got that new rev of that app, right? But there’s no difference between 100 million and 10,000, you know? They’re just ‘the rest of the world’.

"So it’s like when I started out making music and I listened to the radio and there was all this mediocrity. So I set out to set myself apart from that and do something above and beyond that would really express myself and really be different.

"And that’s still the goal. Even if there are 10 million people making AI music you’ll still be asking ‘How can I create something that couldn't have been done by an AI’? Something that didn’t cut corners. So maybe the answer is that I need to harness the power of that AI to do something that has never been done before…

"I'm not a big follower of art, but I saw some AI enhanced art, and it was amazing. It looked like sort of Dada or Bauhaus. People dancing, with human faces, but in the most extraordinary outfits. And I realised that this had been made with AI.

"It was by David Szauder and it was an extraordinary thing that couldn't have existed even a few years ago. It was absolutely mesmerising. And seeing that just gave me hope for music as well."

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“This upcoming tour will be the last time you get a chance to see me for quite sometime. I am going on a vacation”: Devin Townsend announces an indefinite break from touring – but it sounds like he's going to be keeping himself busy in the coming months

"Live right up to the last breath and stay positive about the world, your family and the environment you live in": The Alarm’s Mike Peters has died aged 66